Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Mercator 1569 world map

First map in Mercator's projection From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Mercator world map of 1569 is titled Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigantium Emendate Accommodata (Renaissance Latin for "New and more complete representation of the terrestrial globe properly adapted for use in navigation"). The title shows that Gerardus Mercator aimed to present contemporary knowledge of the geography of the world and at the same time 'correct' the chart to be more useful to sailors. This 'correction', whereby constant bearing sailing courses on the sphere (rhumb lines) are mapped to straight lines on the plane map, characterizes the Mercator projection. While the map's geography has been superseded by modern knowledge, its projection proved to be one of the most significant advances in the history of cartography, inspiring the 19th century map historian Adolf Nordenskiöld to write "The master of Rupelmonde stands unsurpassed in the history of cartography since the time of Ptolemy."[2] The projection heralded a new era in the evolution of navigation maps and charts and it is still their basis.

The map is inscribed with a great deal of text. The framed map legends (or cartouches) cover a wide variety of topics: a dedication to his patron and a copyright statement; discussions of rhumb lines; great circles and distances; comments on some of the major rivers; accounts of fictitious geography of the north pole and the southern continent. The full Latin texts and English translations of all the legends are given below. Other minor texts are sprinkled about the map. They cover such topics as the magnetic poles, the prime meridian, navigational features, minor geographical details, the voyages of discovery and myths of giants and cannibals. These minor texts are also given below.

A comparison with world maps before 1569 shows how closely Mercator drew on the work of other cartographers and his own previous works, but he declares (Legend 3) that he was also greatly indebted to many new charts prepared by Portuguese and Spanish sailors in the portolan tradition. Earlier cartographers of world maps had largely ignored the more accurate practical charts of sailors, and vice versa, but the age of discovery, from the closing decade of the fifteenth century, stimulated the integration of these two mapping traditions: Mercator's world map is one of the earliest fruits of this merger.

Remove ads

Extant copies and facsimiles

Summarize

Perspective

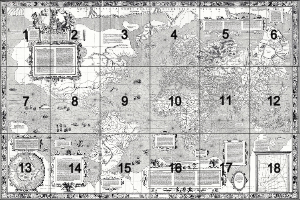

Mercator's 1569 map was a large planisphere,[3] i.e. a projection of the spherical Earth onto the plane. It was printed in eighteen separate sheets from copper plates engraved by Mercator himself.[4] Each sheet measures 33×40 cm and, with a border of 2 cm, the complete map measures 202×124 cm. All sheets span a longitude of 60 degrees; the first row of 6 sheets cover latitudes 80°N to 56°N, the second row cover 56°N to 16°S and the third row cover 16°S to 66°S: this latitude division is not symmetric with respect to the equator thus giving rise to the later criticism of a Euro-centric projection.[5]

It is not known how many copies of the map were printed, but it was certainly several hundred.[6] Despite this large print run, by the middle of the nineteenth century there was only one known copy, that at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. A second copy was discovered in 1889 at the Stadt Bibliothek of Breslau[7] along with maps of Europe and Britain.[citation needed] These three maps were destroyed by fire in 1945 but fortunately copies had been made before then.[8] A third copy was found in a map collection Mappae Geographiae vetustae from the archives of the Amerbach family which had been given to the library of the University of Basel.[9] The only other complete copy was discovered at an auction sale in Luzern in 1932 and is now in the map collection of the Maritiem Museum Rotterdam. [10][11] In addition to the complete copies there is a single page showing the North Atlantic in the Mercator atlas of Europe in the British Library.[12] Many paper reproductions of all four maps have been made. Those at full scale, providing access to the detail and the artistry of Mercator's engraving, are listed next. Images of the Basil, Paris, and Rotterdam impressions can be found online.

Basel map

The Basel map is the cleanest of the three extant versions. It is called the 'three strip' version because it is in three separate rows rather than a single assembled sheet. It was photographically reproduced at a reduced scale by Wilhelm Kruecken in 1992; more recently (2011) he has produced a full-scale and full sized (202×124 cm) reproduction of the map along with a five volume account (in German) covering all aspects of Mercator's work.[13] Medium resolution scans of the separate sheets and a composite of all 18 scans are accessible as follows.

|

Links to the

|

Paris map

The Paris copy is a single combined sheet that came into the possession of the Bibliothèque Nationale from the estate of Julius Klaproth (1783–1835).[9] The map is uncoloured, partially borderless and in poor condition due to repeated exhibitions during the nineteenth century.[9] It was reproduced by Edmé-François Jomard (1777–1862) between 1842 and 1862 as part of a collection of 21 facsimile maps. Very few copies of this facsimile are known.

The Bibliothèque Nationale has put a digital image of their copy into the public domain in the form of 13 separate images.[14] The images do not correspond exactly with the 18 original sheets: they are in three rows of different heights with 5, 4, 4 images respectively. The zoomable images permit examination of small sections of the map in very great detail. These are the only online images at a high enough resolution to read the smallest text.

Breslau map

Immediately after its discovery in 1889 the Breslau map was described by Heyer[8] who initiated copies (in multiple sheets) for the Berlin Geographical Society in 1891.[15] Forty years later, in 1931, a further 150 copies were issued by the Hydrographic Bureau

Rotterdam map

This copy in the Maritiem Museum Rotterdam is in the form of an atlas[16] constructed by Mercator for his friend and patron Werner von Gymnich.[17] It was made by Mercator in (or shortly after) 1569 by dissecting and reassembling three copies of his original wall map to create coherent units such as continents or oceans or groups of legends.[18] There are 17 non-blank coloured pages which may be viewed online (and zoomed to a medium resolution, much lower than that of the French copy at the Bibliothèque Nationale).[19]

In 1962 a monochrome facsimile of this atlas was produced jointly by the curators of the Rotterdam museum and the cartographic journal Imago Mundi.[20] The plates are accompanied with comprehensive bibliographic material, a commentary by van 't Hoff and English translations of the Latin text from the Hydrographics Review.[21] More recently, in 2012, the Maritiem Museum Rotterdam produced a facsimile edition of the atlas, with an introduction by Sjoerd de Meer.[22]

World and regional maps before 1569

Some world maps of the Renaissance up to 1569 — various projections

- Claudius Ptolemy 1482

- Cantino c. 1502 (Padrão Real)

- Waldseemüller 1508

- Pietro Coppo 1520

- D. Ribeiro 1529 (Padrón Real)

- Oronce Fine 1531

- Oronce Fine 1536

- Mercator 1538

- Jean Rotz 1542

- Giacomo Gastaldi 1548

- Ortelius 1570[23]

Some regional maps before 1569

- 1500 Juan de la Cosa

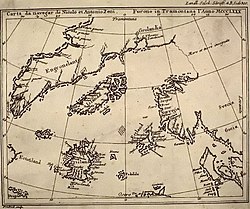

- The Zeno map 1558

- Gutiérrez 1562

Principal features of the 1569 Mercator map

Summarize

Perspective

Mercator's projection

In Legend 3 Mercator states that his first priority is "to spread on a plane the surface of the sphere in such a way that the positions of places shall correspond on all sides with each other, both in so far as true direction and distance are concerned and as correct longitudes and latitudes". He goes on to point out the deficiencies of previous projections,[24] particularly the distortion caused by the oblique incidence of parallels and meridians which gives rise to incorrect angles and shapes: therefore he adopts parallel meridians and orthogonal parallels. This is also a feature of sixteenth-century plane charts (equirectangular projections) but they also have equally spaced parallels; in Legend 3 Mercator also emphasizes the distortion that this gives rise to. In particular, the straight lines emanating from the compass roses are not rhumb lines so that they do not give a true bearing. Nor was it straightforward to calculate the sailing distances on these charts. Mariners were aware of these problems and had evolved rules of thumb[citation needed] to enhance the accuracy of their navigation.

Mercator presents his remedy for these problems: "We have progressively increased the degrees of latitude towards each pole in proportion to the lengthenings of the parallels with reference to the equator." The resulting variation of the latitude scale is shown on the meridian at 350°E of his map. Later, Edward Wright and others showed how this statement of Mercator could be turned into a precise mathematical problem whose solution permitted the calculation of the latitude scale, but their methods had not been developed at the time of Mercator.[25] All these methods hinge on the observation that the circumference of a parallel of latitude is proportional to the cosine of the latitude, which is unity at the equator and zero at the poles. The length of a parallel, and hence the spacing of the parallels, must therefore be increased by a factor equal to the reciprocal of the cosine (i.e. the secant) of the latitude.

Mercator left no explanation of his own methods but, as long ago as 1541, he had demonstrated that he understood how to draw rhumb lines on a globe.[26] It has been suggested that he drew the rhumbs by using a set of metal templates for the seven principal compass points within each quadrant, as follows.[citation needed] Starting at the equator draw a short straight line segment, at say 67.5° (east by northeast). Continue as far as a meridian separated by only two or three degrees of longitude and mark the crossing point. Move the template to that point and repeat the process. Since the meridians have converged a little the line will bend up a little generating a rhumb which describes a spiral on the sphere. The latitude and longitude of selected points on the rhumb could have then been transferred to the chart and the latitude scale of the chart adjusted so that the rhumb becomes a straight line. There has been no shortage of proposed methods for the construction. For example, Hollander analyzed fourteen such hypotheses and concluded that Mercator may have used a judicious mix of mechanical transference and numerical interpolations.[27] However he proceeded, Mercator achieved a fairly accurate, but not perfect, latitude scale.[28]

Since the parallels shrink to zero length as they approach the pole they have to be stretched by larger and larger amounts. Correspondingly the parallel spacing must increase by the same ratio. Mercator concludes that "The chart cannot be extended as far as the pole, for the degrees of latitude would finally attain infinity." —Legend 6. (That is, the reciprocal of the cosine of the latitude become infinite). He therefore uses a completely different projection for the inset map of the north polar regions: an azimuthal equidistant projection.

It took many years for Mercator's projection to gain wider acceptance. The following gallery shows the first maps in which it was employed. General acceptance only came with the publication of the French sea atlas "Le Neptune Francois"[citation needed] at the end of the seventeenth century: all the maps in this widely disseminated volume were on the Mercator projection.[29]

Distances and the Organum Directorium

In Legend 12 Mercator makes careful distinction between great circles (plaga) and rhumb lines (directio) and he points out that the rhumb between two given points is always longer than the great circle distance, the latter being the shortest distance between the points. However, he stresses that over short distances (which he quantifies) the difference may be negligible and a calculation of the rhumb distance may be adequate and more relevant since it is the sailing distance on a constant bearing. He gives the details of such a calculation in a rather cumbersome fashion in Legend 12 but in Legend 10 he says that the same method can be applied more readily with the Organum Directorium (the Diagram of Courses, sheet 18) shown annotated here. Only dividers were used in these constructions but the original maps had a thread attached at the origin of each compass rose. Its use is partially explained in Legend 10.

To illustrate his method take A at (20°N,33°E) and B at (65°N,75°E). Plot the latitude of A on the left hand scale and plot B with the appropriate relative latitude and longitude. Measure the azimuth α, the angle MAB: it can be read off the compass scale by constructing OP parallel to AB; for this example it is 34°. Draw a line OQ through the origin of the compass rose such that the angle between OQ and the equator is equal to the azimuth angle α. Now find the point N on the equator which is such that the number of equatorial degrees in ON is numerically equal to the latitude difference (45° for AM on the unequal scale). Draw the perpendicular through N and let it meet OQ at D. Find the point E such that OE=OD, here approximately 54°. This is a measure of the rhumb line distance between the points on the sphere corresponding to A and B on the spherical Earth. Since each degree on the equator corresponds to 60 nautical miles the sailing distance is 3,240 nautical miles for this example. If B is in the second quadrant with respect to A then the upper rose is used and if B is west of A then the longitude separation is simply reversed. Mercator also gives a refined method which is useful for small azimuths.

The above method is explained in Legend 12 by using compass roses on the equator and it is only in Legend 10 that he introduces the Organum Directorium and also addresses the inverse problems: given the initial point and the direction and distance of the second find the latitude and longitude of the second.

Mercator's construction is simply an evaluation of the rhumb line distance in terms of the latitude difference and the azimuth as[30]

If the latitude difference is expressed in arc minutes then the distance is in nautical miles.

In later life Mercator commented that the principles of his map had not been understood by mariners but he admitted to his friend and biographer, Walter Ghym, that the map lacked a sufficiently clear detailed explanation of its use.[31] The intention expressed in the last sentence of Legend 10, that he would give more information in a future 'Geographia', was never realized.

Prime meridian and magnetic pole

In Legend 5 Mercator argues that the Prime Meridian should be identified with that on which the magnetic declination is zero, namely the meridian through the Cape Verde islands, or alternatively that through the island of Corvo in the Azores. (He cites the varying opinions of the Dieppe mariners). The prime meridian is labelled as 360 and the remainder are labelled every ten degrees eastwards. He further claims that he has used information on the geographical variation of declination to calculate the position of the (single) magnetic pole corresponding to the two possible prime meridians: they are shown on Sheet6 with appropriate text. (For good measure he repeats one of these poles on Sheet 1 to emphasize the overlap of the right and left edges of his map; see text). He does not show a position for a south magnetic pole. The model of the Earth as a magnetic dipole did not arise until the end of the seventeenth century,[citation needed] so between AD 1500 and that era the number of magnetic poles was a matter for speculation, variously 1, 2 or 4.[32] Later, he accepted that magnetic declination changed in time, thus invalidating his position that the prime meridian could be chosen on these grounds.

Geography

In his introduction to the Imago Mundi facsimile edition t' Hoff gives lists of world maps and regional maps that Mercator may well have seen, or even possessed by the 1560s.[33] A more complete illustrated list of world maps of that time may be compiled from the comprehensive survey of Shirley. Comparisons with his own map show how freely he borrowed from these maps and from his own 1538 world map[34] and his 1541 globe.[citation needed]

In addition to published maps and manuscripts Mercator declares (Legend 3) that he was greatly indebted to many new charts prepared by Portuguese and Spanish sailors in the portolan traditions. "It is from an equitable conciliation of all these documents that the dimensions and situations of the land are given here as accurately as possible." Earlier cartographers of world maps had largely ignored the more accurate practical charts of sailors, and vice versa, but the age of discovery, from the closing decades of the fifteenth century, brought together these two traditions in the person of Mercator.[35]

There are great discrepancies with the modern atlas. Europe, the coast of Africa and the eastern coast of the Americas are relatively well covered but beyond that the anomalies increase with distance. For example, the spectacular bulge on the western coast of South America adapted from Ruscelli's 1561 Orbis Descriptio replaced the more accurate representation of earlier maps. That mistake disappears for good with the Blaeu map of 1606.[36]

The Mediterranean basin shows errors similar to those found in contemporary maps. For example, the latitude of the Black Sea is several degrees too high, like in the maps made by Diogo Ribeiro in Seville in the 1520s.[37] However, in Mercator's map the longitude of the entire basin is exaggerated by about 25%, contrary to the very accurate shape depicted by Ribeiro.[38]

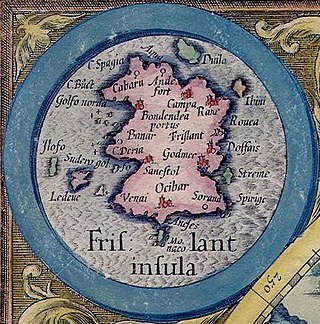

The phantom islands of Frisland and Brasil in the North Atlantic persist in the maps of the period even though they were in waters readily accessed by European sailors. He does show a Strait of Anian between Asia and the Americas as well as NW and NE passages to the spice islands of the East: this he justifies on his studies of the ancient texts detailed in Legend 3 for as yet these were unexplored regions.

The bizarre representation of the geography of the north polar regions in the inset is discussed in detail in Legend 6 and in the minor texts of sheet 13. Mercator uses as his reference a fourteenth-century English friar and mathematician who used an astrolabe to survey the septentrional regions. The four channels carry the sea towards the pole where it disappears into an abyss with great force.

Mercator accepted current beliefs in the existence of a large Southern continent (Terra Australis) — beliefs which would prevail until the discovery of the open seas south of Cape Horn and the circumnavigation of Australia.[39] His biographer, Walter Ghim, explained that even though Mercator was not ignorant that the Austral continent still lay hidden and unknown, he believed it could be "demonstrated and proved by solid reasons and arguments to yield in its geometric proportions, size and weight, and importance to neither of the other two, nor possibly to be lesser or smaller, otherwise the constitution of the world could not hold together at its centre".[40]

Beyond Europe the interiors of the continents were unknown but Mercator struggled to combine the scattered data at his disposal into a harmonious whole in the map legends which speculate on the Asian Prester John and the courses of the Ganges, Nile and Niger. For his geographical information Mercator quotes (Legends 3, 4, 8, 11, 14) classic authors such as Pliny the Elder, Pomponius Mela, Ptolemy, and earlier travellers such as Marco Polo but, as the principal geographer of his time, he would have undoubtedly have been in touch with contemporary travellers.

Navigational inaccuracy

Mercator was not a navigator himself and, while he was obviously aware of the concept of rhumb line, he missed several key practical aspects of navigation. As a result, his world map "was useless for navigation at the time it was created because navigation was something very different from his idealized concept".[37]

Mercator had to work from the geographic information contained in his source maps, which of course was not always accurate, but he may have also introduced errors of his own by misinterpreting the mathematical structure of the Portuguese and Spanish charts of his time. In addition, even if his sources had been perfect, Mercator's map would have still been of little practical use for navigators due to lack of reliable data on magnetic declination and to the difficulty of determining longitude accurately at sea.[37]

These technical reasons explain why Mercator's projection was not widely adopted for marine charts until the 18th century.[37]

Decorative features

High resolution details

The ornate border of the map shows the 32 points of the compass. The cardinal appoints appear in various forms: west is Zephyrus, Occides, West, Ponente, Oeste; east is Subsola, Oriens, Oost, Levante, Este; south is Auster, Meridio, Zuya Ostre, Sid; north is Boreas, Septentrio, Nord, tramontana. All of the other 28 points are written only in Dutch, confirming Mercator's wish that his map would be put to practical use by mariners.

Within the map Mercator embellishes the open seas with fleets of ships, sea creatures, of which one is a dolphin, and a striking god-like figure which may be Triton. The unknown continental interiors are remarkably devoid of creatures and Mercator is for the most part content to create speculative mountain ranges, rivers and cities. The only land animal, in South America, is shown as "... having under the belly a receptacle in which it keeps its young warm and takes them out but to suckle them." ((40°S,295°E) with text.) He also shows cannibals but this may have been true. The giants shown in Patagonia may also be founded in truth: the reaction of Spanish sailors of slight stature on confronting a tribe of natives who were well over six foot in height. These images of South Americans are almost direct copies of similar figures on the #World and regional maps before 1569 map of Diego Gutierrez.[41] There are three other images of figures: Prester John in Ethiopia (10°N,60°E); a tiny vignette of two 'flute' players (72°N,170°E) (see text); the Zolotaia baba at (60°N,110°E). (Zolotaia baba also may be found on the Mercator map of the North Pole near the right border at mid-height).

The italic script used on the map was largely developed by Mercator himself. He was a great advocate of its use, insisting that it was much clearer than any other. He published an influential book, Literarum latinorum, showing how the italic hand should be executed.[42]

Remove ads

Texts of the map

Summarize

Perspective

|

Links to the |

Summary of the legends

- Legend 1 The dedication to his patron, the Duke of Cleves.

- Legend 2 A eulogy, in Latin hexameters, expressing his good fortune at living in Cleves after having fled from persecution by the Inquisition.

- Legend 3 Inspectori Salutem: greetings to the reader. Mercator sets forth three motivations for his map: (1) an accurate representation of locations and distances corrected for the use of sailors by the adoption of a new projection; (2) an accurate representation of countries and their shapes; (3) to stay true to the understanding of ancient writers.

- Legend 4 The Asian Prester John and the origin of the Tartars.

- Legend 5 The prime meridian and how a logical choice could be made on the basis of a study of magnetic declination.

- Legend 6 The north polar (septentrional) regions.

- Legend 7 Magellan's circumnavigation of the world.

- Legend 8 The Niger and Nile rivers and their possible linkage.

- Legend 9 Vasco de Gama.

- Legend 10 The use of the Organum Directorium, the Diagram of courses, for the measurement of rhumb line distance.

- Legend 11 The southern continent Terra Australis and its relation to Java.

- Legend 12 The distinction between great circles and rhumb lines and the measurement of the latter.

- Legend 13 The 1493 papal bull arbitrating on the division between Spanish and Portuguese spheres of influence.

- Legend 14 The Ganges and the geography of south-east Asia.

- Legend 15 The copyright notice.

Legend texts

The following literal translations are taken, with permission of the International Hydrographics Board, from the Hydrographic Review.[21] The Latin text differs from that of Mercator in using modern spelling. Punctuation has been modified or added. Paragraph breaks have been added where required.

Minor texts

| Sheet 1 | ||

|

75°N,182°E |

Polus magnetis. Hunc altero fine tabulae in sua latitudine repetitum vides, quemadmodum et reliquas descriptiones extremitates, quae hoc tabulae latus finiunt, quod ideo factum est ut utriusque termini ad alterum continuato clarius oculis subjecta esset. |

Magnetic Pole. Ye see it repeated at the other end of the chart in the proper latitude as also the other extremities of the representation which terminate at this side of the chart; this was done in order that the continuity of each of the two ends with the other shall more clearly be set before your eyes. |

|

75°N,205°E |

Deserta regio et plana in qua equi sylvestres sunt plurimi, et oves item sylvestres, quales Boethus in descriptione regni Scotiae narrat esse in una Hebridum insularum. |

Desert and flat region in which are very many wild horses and also wild sheep such as Boece declares, in his description of the kingdom of Scotland, are to be found in one of the isles of the Hebrides. |

| Sheet 2 | ||

|

64°N,275°E |

Hic mare est dulcium aquarum, cujus terminum ignorari Canadenses ex relatu Saguenaiensium aiunt. |

Here is the sea of sweet waters, of which, according to the report of the inhabitants of Saguenai, the Canadians say that the limits are unknown. |

|

56°N,290°E |

Hoc fluvio facilior est navigatio in Saguenai. |

By this river navigation towards Saguenai is easier. |

| Sheet 3 | ||

|

70°N,300°E |

Anno Domini 1500 Gaspar Corterealis Portogalensis navigavit ad has terras sperans a parte septentrionali invenire transitum ad insulas Moluccas, perveniens autem ad fluvium quem a devectis nivibus vocant Rio nevado, propter ingens frigus altius in septentrionem pergere destitit, perlustravit autem littora in meridiem usque ad C. Razo. |

In the year of Our Lord 1500 Gaspar Corte-Real, a Portuguese, sailed towards these lands hoping to find, to the Northward, a passage towards the Molucca Isles, but coming near the river which, on account of the snow which it carries in its course, is called Rio Nevado, he abandoned the attempt to advance further North on account of the great cold, but followed the shore Southward as far as Cape Razo. |

|

70°N,300°E |

Anno 1504 Britones primi ioveoerunt littora novae Franciae circa ostia sinus S. Laurentii. |

In the year 1504 some Bretons first discovered the shores of New France about the mouth of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. |

|

70°N,300°E |

Anno 1524 Joannes Verrazzanus Florentinus nomine regis Gall: Francisci primi ex portu Diepa profectus 17 Martii ad littus meridionale novae Fraciae pervenit circa 34 gradum latitud: atque inde versus orientem omne littus perlustravit usque ad Britonum promontorium. |

In the year 1524 the Florentine, Giovanni Verrazzano, sailed in the name of the King of France, Francis I, on 17 March from the port of Dieppe, reached the south coast of New France in about the 34th degree of latitude and thence followed the whole coast to the eastward as far as the Cape of the Bretons. |

|

70°N,300°E |

Anno 1534 duce classis Jacobo Cartier lustrata fuit nova Francia et proximo anno regi Galliae conquiri coepit. |

In the year 1534, Jacques Cartier being leader of the fleet, New France was examined and, in the following year, its conquest for the King of France was undertaken. |

|

75°N,335°E |

Groclant insula cujus incolae Suedi sunt origine. |

Isle of Groclant the inhabitants of which are Swedes by origin. |

|

64°N,355°E |

Hekelfort prom: perpetuo fumos saepe etiam flammas eructans |

Hekelfort Promontory which continually vomits forth smoke and frequently even flames. |

|

58°N,345°E |

Drogeo, Dus Cimes Callis. |

Drogeo, the Dus Cimes of the French. |

| Sheet 4 | ||

|

73°N,48°E |

Semes saxum et promontorium, quod praetereuntes nautae projecto munere pacant ne tempestate obruantur. |

The rock and promontory of Semes, which the seamen who double it appease by casting presents to it, in order that they shall not be victims of tempests. |

|

73°N,52°E |

Swentinoz hoc est sacrum promontorium. |

Swentinoz, that is the Sacred Promontory. |

| Sheet 5 | ||

|

70°N,95°E |

Camenon poyas, hoc est orbis terrae cingulum mons, Hyperboreus veteribus, Riphaeus Plinio. |

Camenon poyas, that is the mountain which serves as a belt for the Universe, the Hyperboreas of the ancients and the Ripheus of Pliny. |

|

68°N,115°E |

Lytarnis primum Celticae promont: Plinio. |

Lytarmis, according to Pliny, the first promontory of Celtica. |

|

62°N,112°E |

Samogedi id est se mutuo comedentes. |

Samogeds, that is the people who devour each other. |

|

60°N,105°E |

Oby fluvius sesquidiei remigatione latus. |

The River Oby the width of which is such that a day and a half is required to cross it in a rowing boat. |

|

59°N,105°E |

Perosite ore angusto, odore coctae carnis vitam sustentant. |

Perosite, with narrow mouths, who live on the odour of roast flesh. |

|

66°N,105°E |

Per hunc sinum mare Caspium erumpere crediderunt Strabo, Dionysius poeta, Plinius, Solinus et Pomponius Mela, fortasse lacu illo non exiguo, qui Obi fluvium effundit, opinionem suggerente. |

Strabo, the poet Dionysius, Pliny, Solinus and Pomponius Mela believed that the Caspian Sea opened out into this gulf, this idea being suggested perhaps by the somewhat vast lake from which the Obi River flows. |

| Sheet 6 | ||

|

78°N,130°E |

In septentrionalibus partibus Bargu insulae sunt, inquit M. Paulus Ven: lib.1, cap.61, quae tantum vergunt ad aquilonem, ut polus arcticus illis videatur ad meridiem deflectere. |

In the northern parts of Bargu there are islands, so says Marco Polo, the Venetian, Bk.1, chap.61, which are so far to the north that the Arctic pole appears to them to deviate to the southward. |

|

77°N,175°E |

Hic erit polus maguetis, si meridianus per insulam Corvi primus dici debeat. |

It is here that the magnetic pole lies if the meridian which passes through the Isle of Corvo be considered as the first. |

|

72°N,170°E |

Hic polum magnetis esse et perfectissimum magnetem qui reliquos ad se trahat certis rationibus colligitur, primo meridiano quem posui concesso . |

From sure calculations it is here that lies the magnetic pole and the very perfect magnet which draws to itself all others, it being assumed that the prime meridian be where I have placed it. |

|

68°N,170°E |

Hic in monte collocati sunt duo tubicines aerei, quos verisimile est Tartarorum in perpetuam vindicatae libertatis memoriam eo loci posuisse, qua per summos montes in tutiora loca commigrarunt. |

At this place, on a mountain, are set two flute-players in bronze who probably were put here by the Tartars as an everlasting memorial of the attainment of their freedom at the place at which, by crossing some very high mountains, they entered countries where they found greater safety. |

|

59°N,160°E |

Tenduc regnum in quo Christiani ex posteritate Presbiteri Joannis regnabant tempore M. Pauli Ven: anno D. I290. |

The Kingdom of Tenduc over which Christian descendants of Prester John reigned in the time of Messer Polo, the Venetian, in the year 1280. |

| Sheet 7 | ||

|

°N,°E |

Nova Guinea quae ab Andrea Corsali Florentino videtur dici Terra de piccinacoli. Forte Iabadii insula est Ptolomeo si modo insula est, nam sitne insula an pars continentis australis ignotum adhuc est. |

New Guinea which seemingly was called by Andrea Corsalis, the Florentine, the Land of the Dwarfs. Perchance it is the Isle of Jabadiu of Ptolemy if it really be an isle, for it is not yet known whether it be an isle or a part of the Southern Continent. |

|

°N,°E |

Insulae duae infortunatae, sic a Magellano appellatae, quod nec homines nec victui apta haberent. |

The two Unfortunate Isles, so called by Magellan, for that they held neither men nor victuals. |

| Sheet 9 | ||

|

28°N,315°E |

Anno D. 1492, 11 Octobris Christophorus Columbus novam Indian nomine regis Castellae detexit, prima terra quam conquisivit fuit Haiti. |

In the year of Our Lord 1492 on 11 October Christopher Columbus, in the name of the King of Castille, discovered the New Indies. The first land conquered by him was Haiti. |

|

8°N,275°E |

Maranon fluvius inventus fuit a Vincentio Yanez Pincon an: 1499, et an: 1542 totus a foutibus fere, ad ostia usque navigatus a Francisco Oregliana leucis 1660, mensibus 8, dulces in mari servat aquas usque ad 40 leucas. |

The River Maranon was discovered by Vicente Yáñez Pinzón in 1499, and in 1542 it was descended in its entirety, almost from its sources to its mouth, by Francisco Oregliana, over a course of 1,660 leagues during 8 months. It maintains its sweet waters in the sea for 40 leagues from the coast. |

|

12°S,350°E |

Portus regalis in quem Franci et Britanni mercatum navigant. |

Port Royal to which the French and the English repair for trade. |

| Sheet 11 | ||

|

55°N,110°E |

Care desertum per quod in Cathaium eunt ac redeunt Tartari. |

The desert of Cara by which the Tartars pass when going to Cathay or returning therefrom. |

|

52°N,115°E |

Karakithay id est nigra Kathaya. |

Karakithai, that is to say Black Cathay. |

|

40°N,115°E |

Pamer altissima pars totius continentis. M. Paul Ven : lib.5 |

Pamer, the highest part of the whole continent, M. Polo, the Venetian, Bk.9. |

|

45°N,85°E |

Mare de Sala, vel de Bachu, Ruthenis Chualenske more, olim Casitum et Hircanum. |

The Sala or Bachu Sea, the Chualenske more of the Ruthenians, formerly Caspian and Hircanian Sea. |

|

5°N,115°E |

Zeilam insula Tearisim incolis dicta, Ptol : Nauigeris. |

Isle of Zeilam called by the inhabitants Tenarisim, the Nanigeris of Ptolemy. |

|

8°N,88°E |

Mare Rubrum quod et Aethiopicum Dionyso, juxta quem et Pomp: Melam ad Taprobauam usque extenditur. |

The Red Sea which Dionysius calls also the Ethiopic Sea. According to Dionysius and Pom. Meta it extends as far as Taprobana. |

| Sheet 12 | ||

|

55°N,165°E |

Cianganor id est lacus albus forte eadem est Coccoranagora Ptol : |

Cianganor, which is to say White Lake, perhaps the same as Ptolemy's Coccoranagora. |

|

50°N,175°E |

Tamos promont: Melae, quod ab Orosio videtur dici Samara. |

The Promontory of Tamos according to Mela, which seems to be called Samara by Orosius. |

|

47°N,137°E |

Lacus salsus in quo margaritarum magna copia est. |

Salt lake in which pearls exist in extreme abundance. |

|

38°N,127°E |

Formicae hic aurum effodientes homines sunt. |

Here there are men who unearth the gold of ants. |

|

42°N,155°E |

Magnus sinus Ptol: Chrise Pliu: hodie mare Cin, a Cin regno (quod est Mangi) sic an apanitis appellato. |

The Great Gulf of Ptolemy, the Chrise of Pliny, now Sea of Ci, thus called by the Japanese of the Kingdom Chin (namely Mangi). |

|

35°N,168°E |

Japan dicta Zipangri a M. Paulo Veneto, olim Chrise. |

Japan, called Zipagri by M. Polo the Venetian. Formerly Chrise. |

|

25°N,154°E |

Bergatera insula a donde se haze la benjaga. |

Bergatera Isle whence gum benjamin is got. |

|

18°N,163°E |

Barussae insulae praecipuae sunt 5 istae Mindanao Cailon Subut cum reliquis duabus Circium versus, Sindae autem 3 praecipuae Celebes Gilolo et Ambon. |

The principal Barusse Isles are the 5 following : Mindanao, Cailon, Subut and two others to the northwestward; the three principal Sinde isles are Celebes, Gilolo and Ambon. |

|

13°S,170°E |

Moluccae vocantur 5 insulae ordine positae juxta Gilolo, quarum suprema Tarenate, sequentes deinceps Tidore Motir Machiam et infima Bachian. |

Five islauds set in a row beside Gilolo are called Moluccas, the highest is Tarenata, thereafter come Tidore, Motir, Machiam and the lowest is Bachian. |

| Sheet 13 | ||

|

74°N,190°E |

LATIN |

ENGLISH |

|

77°N,180°E |

LATIN |

ENGLISH |

|

80°N,220°E |

Oceanus 19 ostiis inter has insulas irrumpens 4 euripos facit quibus indesinenter sub septentrionem fertur, atque ibi in viscera terrae absorbetur. |

The ocean breaking through by 19 passages between these isles forms four arms of the sea by which, without cease, it is carried northward there being absorbed into the bowels of the Earth. |

|

80°N,100°E |

Hic euripus 5 habet ostia et propter angustiam ac celerem fluxum nunquam |

This arm of the sea has five passages and, on account of its straitness and of the speed of the current it never freezes. |

|

80°N,350°E |

Hic euripus 3 ingreditur ostiis et quotannis at 3 circiter menses congelatus manet, latitudinem habet 37 leucarum. |

This arm of the sea enters by three passages and yearly remains frozen about 3 months; it has a width of 37 leagues. |

|

80°N,70°E |

Pygmae hic habitant 4 ad summum pedes longi, quaemadmodum illi quos in Gronlandia Screlingers vocant. |

Here live pygmies whose length is 4 feet, as are also those who are called the Skræling in Greenland. |

|

80°N,310°E |

Haec insula optima est et saluberrima totius septentrionis. |

This isle is the best and most salubrious of the whole Septentrion. |

| Sheet 14 | ||

|

20°S,270°E |

Hicuspiam longius intra mare in parallelo portus Hacari dicunt nonnulli Indi et Christiani esse insulas grandes et publica fama divites auro. |

Somewhere about here further to seaward on the parallel of Port Hacari some Indians and Christians report that there are some large islands wherein, according to common report, gold abounds. |

|

40°S,295°E |

Tale in his regionibus animal invenitur habens sub ventre receptaculum in quo tenellos fovet catulos, quos non nisi lactandi gratia promit. |

In these parts an animal thus made is found, having under the belly a receptacle in which it keeps its young warm and takes them out but to suckle them. |

| Sheet 15 | ||

|

18°S,340°E |

Bresilia inventa a Portogallensibus anno 1504. |

Brazil was discovered by the Portuguese in 1504. |

|

40°S,305°E |

Indigenae passim per Indiam novam sunt antropophagi. |

The natives of various parts of the New Indies are cannibals. |

|

45°S,315°E |

Patagones gigantes, 1 et ad summum 13 spithamas longi. |

Giant Patagonians, 11 and even 13 spans tall. |

| Sheet 16 | ||

|

42°S,15°E |

Hic in latitudine 42 gr: distantia 450 leucarum a capite bonae spei, et 6oo a promontorio S : Augustini inventum est promont: terrae australis ut annotavit Martinus Fernandus Denciso in sua Summa geographiae. |

Here, in the 42nd degree of latitude, at a distance of 450 leagues from the Cape of Good Hope and 6oo from St. Augustin's Promontory, a headland of the Southern Lands was discovered, as stated by Martin Fernandez de Enciso in his Suma de Geographia. |

|

45°S,40°E |

Psitacorum regio sic a Lusitanis huc lebegio vento appulsis, cum Callicutium peterent, appellata propter inauditam earum avium ibidem magnitudinem, porro cum hujus terrae littus ad 2000 miliarium prosecuti essent, necdum tamen finem invenerunt, unde australem continentem attigisse indubitatum est. |

Region of the Parrots, so called by the Lusitanians, carried along by the libeccio when sailing towards Calicut, on account of the unprecedented size of these birds at that place. As they had followed the coast of this land unto the 2,000th mile without finding an end to it, there was no doubt but that they had reached the Southern Continent. |

| Sheet 17 | ||

|

22°S,82°E |

Haec insula quae ab incolis Madagascar, id est insula lunae, a nostris S. Laurentii vocatur, Plinio lib : 6 cap: 31 videtur esse Cerne, Ptol : est Menuthias. |

This island, called by the inhabitants Madagascar, i.e. Isle of the Moon, is called by us St. Lawrence; it would appear to be the Cerne of Pliny, Bk.6, chapt.31, and the Menuthias of Ptolemy. |

|

37°S,85°E |

Los Romeros insulae, in quibus Ruc avis vasto corpore certo anni tempore apparet. M. Paul Venet : lib:3 cap:40. |

Los Romeros Isles in which, at a certain time of the year, the bird "Ruc" of vast body appears. Marco Polo, the Venetian, Bk.3, chapt.40. |

|

44°S,65°E |

Vehemens admodum est fluxus maris versus ortum et occasum inter Madagascar et Romeros insulas, ita ut difficillima huc illinc sit navigatio, teste M.Paulo Ven: lib:3 cap:40, quare non admodum multum haec littora a Madagascar distare necesse est, ut contractiore alveo orientalis oceanus in occidentalem magno impetu se fundat et refundat. Astipulatur huic Cretici cujusdam Venetorum ad regem Portogalliae legati epistola, quae nudos hie degere viros habet. |

Between Madagascar and Los Romeros Isles there is an extremely violent current of the sea in the East and West direction such that sailing therein is of great difficulty to go from the one to the others according to the testimony of M. Polo, the Venetian, Bk.3, chapt.40; hence necessarily these coasts cannot be very distant from Madagascar so that the eastern ocean should flow and spread through a more narrow bed into the western. This testimony is confirmed by the letter of a Cretan, the Ambassador of Venice to the King of Portugal, who says that naked men live there. |

| Sheet 18 | ||

|

18°S,145°E |

Beach provincia aurifera quam pauci ex alienis regionibus adeunt propter gentis inhumanitatem. |

Beach, a province yielding gold, where few from foreign parts do come on account of the cruelty of the people. |

|

22°S,145°E |

Maletur regnum in quo maxima est copia aromatum. |

Maletur, a kingdom in which there is a great quantity of spices. |

|

28°S,164°E |

Java minor producit varia aromata Europaeis nunquam visa, ut habet M.Paulus Ven : lib:3, cap:13. |

Remove ads Java Minor produces various spices which Europeans have never seen, thus saith Marco Polo, the Venetian, in Bk.3, Chapt.13. |

Bibliography

- Bagrow, Leo (1985), History of cartography [Geschichte der Kartographie] (2nd ed.), Chicago

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Calcoen, Roger; et al. (1994), Le cartographe Gérard mercator 1512 1594, Credit Communal Belgique, ISBN 978-2-87193-202-4Published jointly by the Royal Library of Belgium (Brussels), Plantin-Moretus Museum (Antwerp), Musée Mercator (Sint-Niklaas) on the occasion of the opening of the Musée Mercator de Sint-Niklaas and the exhibition "Le cartographe Gérard Mercator, 1512–1594" at the Royal Library.

- de Meer, Sjoerd (2012), Atlas of the World: Gerard Mercator's map of the world (1569), Walburg Pers, ISBN 978-90-5730-854-3

- Gaspar, Joaquim Alves & Leitão, Henrique (2013), "Squaring the Circle: How Mercator Constructed His Projection in 1569", Imago Mundi, 66: 1–24, doi:10.1080/03085694.2014.845940, S2CID 140165535

- Ghym, Walter (159), Vita Mercatoris Translated in Osley. (Surname also spelled as Ghim)

- Horst, Thomas (2011), Le monde en cartes. Gérard Mercator (1512–1594) et le premier atlas du monde. Avec les reproductions en couleur de l'ensemble des planches de l'Atlas de Mercator de 1595 (2o Kart. B 180 / 3) conservé à la Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Mercatorfonds / Faksimile Verlag, Gütersloh / Munich / Brussels, 400 pp, ISBN 978-90-6153-157-9See Mercator Fonds

- Imhof, Dirk; et al. (1994), Le cartographe Gerard Mercator 1512-1594, Bibliotheque Royale, Bruxelles, ISBN 978-2-87193-202-4

- Imhof, Dirk; Kockelbergh, Iris; Meskens, Ad; Parmentier, Jan (2012), Mercator: exploring new horizons, Plantin-Moretus Museum [Antwerp]. - Schoten : BAI, ISBN 978-90-8586-629-9

- Karrow, R.W. (1993), Mapmakers of the sixteenth century and their maps, Published for the Newberry Library by Speculum Orbis Press, ISBN 978-0-932757-05-0

- Leitão, Henrique & Alves Gaspar, Joaquim (2014), "Globes, Rhumb Tables, and the Pre-History of the Mercator Projection", Imago Mundi, 66 (2): 180–195, doi:10.1080/03085694.2014.902580, S2CID 128800259

- Monmonier, Mark [Stephen] (2004), Rhumb Lines and Map Wars: A Social History of the Mercator Projection, Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-53431-2

- Osley, A. S. (1969), Mercator, a monograph on the lettering of maps, etc. in the 16th century Netherlands, with a facsimile and translation of his treatise on the italic hand ['Literarum latinarum'] and a translation of Ghim's 'Vita Mercatoris, Watson-Guptill (New York ) and Faber (London)

- Renckhoff, W, ed. (1962), Gerhard Mercator, 1512–1594 :Festschrift zum 450. Geburtstag (Duisburger Forschungen), Duisburg-Ruhrort :Verlag fur Wirtschaft und Kultur

- Snyder, John P. (1993), Flattening the Earth: Two Thousand Years of Map Projections., University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-76747-5 This book is an expanded version of the following article, and similar articles, in The History of Cartography.

- Snyder J.P. Cartography in the Renaissance in The History of Cartography, Volume 3, part I, p. 365.

- "Text and Translation of the Legends of the Original Chart of the World by Gerhard Mercator, issued in 1569". Hydrographic Review. 9 (2): 7–45. 1932.

- van Nouhuys, J. W. (1933). "Mercator's World Atlas "ad usum Navigantium"". Hydrographic Review. 10 (2): 237–241.

- van Raemdonck, J (1869), Gerard Mercator, Sa vie et ses oeuvres, St Niklaas

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - van 't Hoff, Bert and editors of Imago Mundi (1961), Gerard Mercator's map of the world (1569) in the form of an atlas in the Maritime Museum Prins Hendrik at Rotterdam, reproduced on the scale of the original, Rotterdam/'s-Gravenhage: Maritime Museum Rotterdam Publication No. 6. Supplement no. 2 to Imago Mundi

{{citation}}:|first=has generic name (help). - Woodward, D. and Harley J.B. (1987), The History of Cartography, Volume 3, Cartography in the European Renaissance, University of Chicago, ISBN 978-0-226-90734-5

Map bibliography

Summarize

Perspective

This bibliography gives lists of world and regional maps, on various projections, that Mercator may have used in the preparation of his world map. In addition there are examples of maps of the succeeding decades which did or did not use the Mercator projection. Where possible references are given to printed or online reproductions.

Atlases and map collections

- Barron, Roderick (1989), Decorative Maps, Londo: Studio Editions, ISBN 978-1-85170-298-5

- Baynton-Williams, Ashley and Miles (2006), New Worlds: maps from the age of discovery, London: Quercus, ISBN 978-1-905204-80-9

- Mercator (1570), Atlas of Europe. There are two online versions in the British Library: the 'Turning the pages' version at and an annotated accessible copy at .

- Nordenskiöld, Adolf Eric (1897), Periplus: An essay on the early history of charts and sailing-direction translated from the Swedish original by Francis A. Bather. With reproductions of old charts and maps., Stockholm

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Nordenskiöld, Adolf Eric (1889), Facsimile-atlas till kartografiens äldsta historia English [Facsimile-atlas to the early history of cartography with reproductions of the most important maps printed in the XV and XVI centuries translated from the Swedish by J. A. Ekelöf and C. R. Markham], Kraus Reprint Corporation and New York Dover Publications London Constable 1973, ISBN 978-0-486-22964-5

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Shirley, Rodney W. (2001), The mapping of the world: early printed world maps 1472-1700 (4 ed.), Riverside, Conn.: Early World Press, ISBN 978-0-9703518-0-7

- Ptolemy, Claudius (1990), Cosmography, Leicester: Magna, ISBN 978-1-85422-103-2. The maps of the Codex Lat V F.32, a 15th-century manuscript in the National Library, Naples.

World maps before 1569

- de la Cosa, Juan (1500), Map of Juan de la Cosa Nordenskiöld Periplus, plate XLIII.

- Ribero, Diego (1529), The second Borgian map by Diego Riber Nordenskiöld plates XLVIII-XLIX .

- Gastaldi, Giacomo (1546), Universale Müller-Baden, Emanuel (Hrsg.): Bibliothek des allgemeinen und praktischen Wissens, Bd. 2. – Berlin, Leipzig, Wien, Stuttgart: Deutsches Verlaghaus Bong & Co, 1904. – 1. Aufl.

- Mercator, Gerardus (1538), 1538 Mercator Map Nordenskiöld Facsimile Atlas, plate XLIII. Shirley plate 79 (entries 74 and 91).

- Ortelius, Abraham (1564), Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Shirley plate 97 (entry 114).

Regional maps before 1569

- Mercator, Gerardus (1554), Map of Europe.

- Gastaldi (1561), Map of Asia Nordenskiöld Periplus, plates LIV, LV, LVI.

- Gastaldi (1564), Map of Africa Nordenskiöld Periplus, plates XLVI.

- Gutierez (1562), Map of South America Bagrow, Plate 86.

World maps using the Mercator projection after 1569

- Hondius, Jodocus (1597), The Christian Knight Map

- Wright (1599), Map for sailing to the Isles of Azores

- Wright, Edward; Moxon, Joseph (1655), A Plat of All the World

- Blaeu, William Janzoon (1606), Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Geographica ac Hydrographiva Tabula. Printed in New Worlds, page 59

Remove ads

See also

Notes

- Cape Prassum has been identified with Mozambique.[44]

- The Gulf of Hesperia has been identified with the River Gambia.[45]

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads