Maya Ulanovskaya

Soviet dissident and Russian-Israeli writer From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Maya Aleksandrovna Ulanovskaya (also known as Maiia Ulanovskie and Maria Ulanovsky) (Russian: Майя Александровна Улановская) (Hebrew: מאיה אולאנובסקאיה) (October 20, 1932 – June 25, 2020), was an American-born Russian-Israeli who, with spouse Anatoly Yakobson, participated in the dissident movement in the USSR and became a professor, writer, and translator in Israel.[1][2][3]

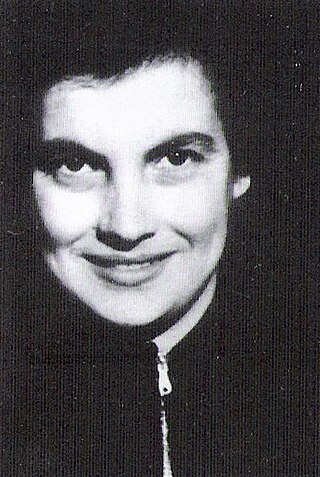

Maya Ulanovskaya | |

|---|---|

| Майя Александровна Улановская | |

Maya Ulanovskaya (circa 1955) | |

| Born | Maya Aleksandrovna Ulanovskaya October 20, 1932 |

| Died | June 25, 2020 (aged 87) |

| Citizenship | Soviet Union Israel |

| Occupation(s) | Literary critic, translator, teacher |

| Movement | Human rights movement in the Soviet Union |

| Spouse | Anatoly Yakobson |

| Children | Alexander Yakobson |

| Parent(s) | Alexander Ulanovsky, Nadezhda Ulanovskaya |

Background

Maya Aleksandrovna Ulanovskaya was born in New York City while her Jewish parents were stationed there as Soviet resident spies and Soviet intelligence officer illegals for the GRU. Her father was Alexander Ulanovsky (1891–1971). Her mother was Nadezhda Ulanovskaya (1903–1986). In a 1952 memoir, Whittaker Chambers, who reported to the Ulanovskys in the early 1930s, noted Nadezhda's pregnancy and also noted that Ulanovskaya had an older brother, "kept hostage at school in Russia (the boy was killed fighting against the Germans during the Nazi invasion)."[4]

Career

Summarize

Perspective

USSR

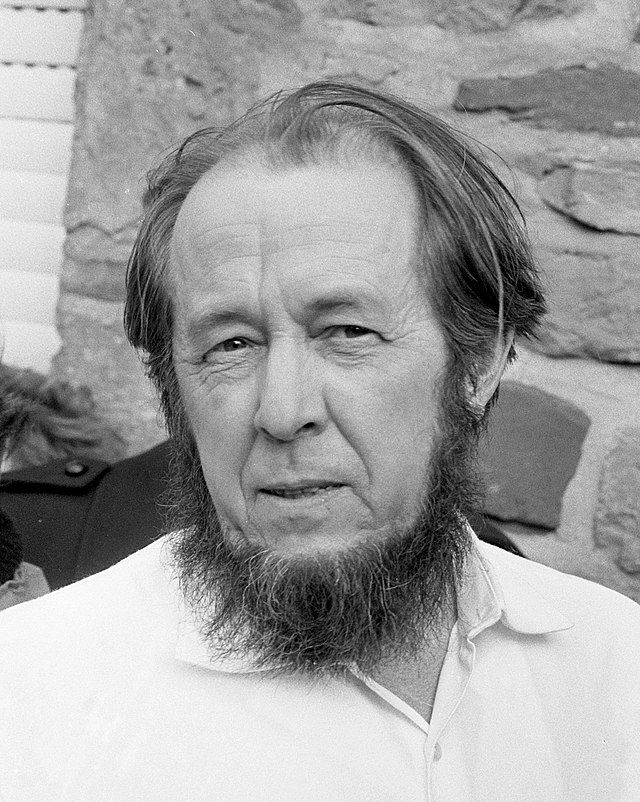

In 1948–1949, Ulanovskaya's parents were arrested on political charges. Her parents were among those cited in The Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.[5][6]

In 1949, Ulanovskaya graduated from school and entered the Moscow Institute of Food Industry. At the institute, she met members of and joined an underground anti-Stalinist organization, organized by students Boris Slutsky, Yevgeny Gurevich, and Vladilen Furman in 1950.[3]

On February 7, 1951, the MGB arrested Ulanovskaya among 15 others. Just over a year later, on February 13, 1952, the Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court arrested and sentenced her to 25 years in the Ozerlag (Озерлаг) MVD special camp, part of the Soviet GULAG labor camp system for political prisoners. Slutsky, Gurevich, and Furman received death sentences, ten received 25-year sentences, and three 10-year sentences. In February 1956, the case was revised, the term of imprisonment was reduced to five years, and she, along with other accomplices, was released under an amnesty.[2][3]

In the 1960s - 1970s, Ulanovskaya worked at the Institute of Scientific Information on Social Sciences of the Russian Academy of Sciences (INION RAN) library in Moscow and participated in the human rights movement by reprinting samizdat, passing information abroad, etc.

Israel

In 1973, Ulanovskaya emigrated with her husband and son to Israel. In 1974, she divorced her husband.

Ulanovskaya worked at the National Library in Jerusalem. She translated into Russian books from English (including some by Arthur Koestler), Hebrew, and Yiddish.

In 1989, Ulanovskaya received rehabilitation from the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the USSR Rehabilitation, based on lack of an evidence and corpus delicti.[3]

Hiss Case

Regarding the Hiss Case, Ulavoskaya's mother wrote (quoted from the new English edition of their memoir):

My story has many parallels with that of Whittaker Chambers. We met the same people, and I can thus confirm his testimony.[7]

Personal life

In 1956, Ulanovskaya married Anatoly Yakobson; in 1959, they had a son, Alexander Yakobson. In 1973, Ulanovskaya immigrated with her husband, son, and mother to Israel.[citation needed]

Works

Summarize

Perspective

Ulanovskaya wrote a memoir with her mother that recounts the lives of two generations of their family.[2][7]

The memoir provides details about:

- The early espionage career of Whittaker Chambers, first documented in English by Allen Weinstein in his book Perjury: The Hiss-Chambers Case.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15]

- Stalinism and Soviet post-war youth[16]

- Women's history[17]

- Russian women writers[18]

Writings:

- История одной семьи (translated History of One Family) (New York: Chalidze, 1982) (Russian)

- История одной семьи (Moscow: Vest-VIMO, 1994)

- История одной семьи (St. Petersburg: INAPRESS, 2003)

- История одной семьи (St. Petersburg: INAPRESS, 2005)

- The Family Story (2016) (Hannover, NH: Seven Arts/Lulu, 2016)[7]

- Jews in the culture of the Russian emigre (1995)

- Internal Plan of Life (on Vladimir Gershuni) (1996)

- Freedom and dogma: the life and work of Arthur Koestler (1996)

- "Why Koestler?" (1997)

- The Jewish National Library and its Russian Roots (1999)

- On Anatoly Yacobson (2010)

- The Serene Breathing of Sadness (2017) by Anatoly Yakobson (compiler)

Translations Hebrew to Russian:

- The Book of Testimony (1989) by Abba Kovner = יום זה: מגילת עדות

- Letters Yoni: portrait of a hero (1984) by Yonatan Netanyahu = מכתבי יוני

- The Last Fight Yoni (2001) by Yonatan Netanyahu = הקרב האחרון של יוני

Translations English to Russian:

- Thieves in the Night (1981) by Arthur Koestler

- The Thirteenth Tribe (1998) by Arthur Koestler

- Arrival and Departure (2017) by Arthur Koestler

Translations Yiddish to Russian:

- My memories (2009, 2012) by Yechezkel Kotik = מיינע זכרונות

See also

References

External sources

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.