Loading AI tools

American geneticist From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

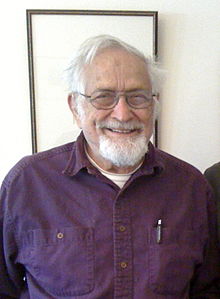

Maurice Sanford Fox (October 11, 1924 – January 26, 2020) was an American geneticist and molecular biologist, and professor of biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he served as department chair between 1985 and 1989. His pioneering investigations of bacterial transformation helped illuminate the mechanisms by which donor DNA enters and is integrated into a host cell. His research also contributed to our understanding of mechanisms of DNA mutation, recombination, and mismatch repair more generally. Ancillary activities include his critical role in the establishment of the Council for a Livable World. He was married to photo researcher Sally Fox,[1] who died in 2006, for over 50 years, and has three sons (Jonathan, Gregory, and Michael). Fox died in January 2020 at the age of 95.[2]

Maurice Sanford Fox | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Maurice Sanford Fox October 11, 1924 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | January 26, 2020 (aged 95) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | University of Chicago |

| Known for | Molecular Biology, Genetic Mutation |

| Awards | Docteur Honoris Causa, Paul Sabatier University, Toulouse, France (1994) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Molecular Biology |

| Institutions | Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| Doctoral advisor | Willard Libby |

| Doctoral students | David Botstein |

| Other notable students | H. Robert Horvitz |

Maurice Fox (Maury) was born of poor Russian Jewish immigrants and spent his formative years living in New York City. He is the brother of Evelyn Fox Keller and, early on, encouraged her work in science.[3] Like many others of his generation, he benefited from an excellent public school system in which a budding interest in science was fostered from an early age. His study of chemistry began at Stuyvesant High School and, after a brief stint at Queens College where he took calculus from Banesh Hoffmann,[3] and another as weather forecaster in the U.S. Army Air Force during WWII, culminated in a Ph.D. under Willard Libby at the University of Chicago in 1951. It was at Chicago that he first met, and soon became a disciple, protégé, friend and colleague of, Leó Szilárd. Szilárd's biography contains many references to Fox.[4] Szilárd recruited him into the small but growing ranks of the new discipline of molecular biology. In 1953, he moved to the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research to work in Roland Hotchkiss' group.

It was a heady time, in which bright young people, coming from a range of scientific disciplines, were challenged to pose questions about biology on which their diverse skills might be brought to bear. This period has often been referred to as the "Golden Age of Molecular Biology,"[citation needed] but its particular ethos shaped Fox's research for the next half century, as he continued to pose novel kinds of, and novel approaches to, questions about molecular genetics, about cancer, about adaptive mutation; to insist on the pursuit of unexamined possibilities; and to free and open sharing of ideas with colleagues and students. His life was also marked by an ongoing commitment (shared with Szilárd) to nurturing the young, and to fulfilling his particular social and political responsibilities as a scientist.[2][5]

Fox's primary achievement in the early part of his career was to turn bacterial transformation into an experimental model for genetic analysis that was to provide key insights into the mechanisms of genetic modification. Later he was to extend the powerful modes of analysis developed in this early work to the investigation of genetic modification in transduction and conjugation as well. But as important as this work was to our understanding of mutation, recombination, and mismatch repair, perhaps equally important was his lifelong insistence on the critical interrogation of available data, on the posing of alternative possible explanations, and on the design of experiments that could test such alternative interpretations. These habits of inquiry were remarkably productive, both in his own work and in the work of the many others with whom he interacted. Directly or indirectly, it led, e.g., to the search for RNA viruses by Tim Loeb (1961), to the discovery of the SOS response in bacteria by Miroslav Radman (1976), and to the development of techniques of bacterial cell fusion by Pierre Shaeffer (1976). It also led him to a very early challenge (based on critical examination of the epidemiological data on breast cancer) to the prevailing confidence among physicians in the efficacy either of radical mastectomy or of mammograms (1979),[6] and to an equally early recognition of the critical importance of epigenetic changes in the initial stages of carcinogenesis (1980).

From the start of his career, Fox was attentive to the social and political implications of scientific actively. He was, e.g., concerned about the biological effects of radiation, the dangers of biological warfare, the risks of gene therapy and (later) of genetic recombination, and on all these issues, he was actively involved in efforts to reduce risks and guarantee public safety. He talked to citizen groups, rallied scientists, wrote editorials and letters for Science, and participated in committees. For example, he chaired the Radiation Protection Committee at MIT in the 1960s, and was a member of the International Bioethics Committee of UNESCO from 1998. But what may have been his most important political and social contribution was his role in helping Szilárd organize the "Council for a Livable World" (originally called "Council for Abolishing War", 1962) and facilitating its operation. This organization served as an early political action committee and was effective in supporting peace candidates for legislative positions throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.