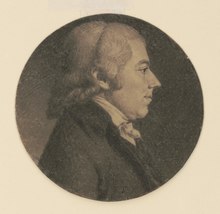

Matthew Clay

American politician From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Matthew Clay (March 25, 1754 – May 27, 1815) was a Virginia lawyer, planter, Continental Army officer and politician who served in the United States House of Representatives and the Virginia House of Delegates representing Pittsylvania County.[1]

Matthew Clay | |

|---|---|

Matthew Clay (portrait) | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia's 15th district | |

| In office March 4, 1815 – May 27, 1815 | |

| Preceded by | John Kerr |

| Succeeded by | John Kerr |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia's 14th district | |

| In office March 4, 1803 – March 3, 1813 | |

| Preceded by | Samuel Jordan Cabell |

| Succeeded by | William A. Burwell |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia's 6th district | |

| In office March 4, 1797 – March 3, 1803 | |

| Preceded by | Isaac Coles |

| Succeeded by | Abram Trigg |

| Member of the Virginia House of Delegates from Pittsylvania County | |

| In office 1790–1794 | |

| Preceded by | William Dix |

| Succeeded by | William Payne |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 25, 1754 Halifax County, Virginia Colony, British America |

| Died | May 27, 1815 (aged 61) Halifax, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Pittsylvania County, Virginia |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouse | Mary Williams |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Continental Army |

| Years of service | 1776–1783 |

| Rank | Quartermaster |

| Unit | Ninth, First and Fifth Virginia Regiments |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War |

Early life

Born to the former Martha Green and her planter husband, Charles Clay, who was the son of Henry Clay of Chesterfield County. His uncle (father's brother) was the grandfather of Henry Clay, who became famous after moving to Kentucky (i.e. Henry Clay was a first cousin). One historian believes Matthew Clay was born in the part of then vast Goochland County that became Cumberland County in 1749 and that in 1777 became Powhatan County. Nothing is known about his schooling, other than that his brothers Rev. Charles Clay (1745–1820) and General Green Clay (1757–1828), who were born in that area were well educated.[1] Other siblings included Rev. Eleazer Clay and Thomas, Henry and Martha Clay.[2] His father had also patented (claimed) much land in what became eastern Pittsylvania County, which Matthew Clay would ultimately inherit from a sibling (but which at the time of Matthew's birth was in Halifax County).

Military service

During the American Revolutionary War Clay joined the Ninth Virginia Regiment on October 1, 1776, as an ensign and probably fought in the New Jersey and Pennsylvania campaigns (but was on detached duty so not present at the disastrous Battle of Germantown).[1] After Clay was promoted to second lieutenant in May 1778, his depleted regiment became part of the First Virginia Regiment, and by year's end he was its quartermaster. However, Clay was not with the regiment when it was sent south, then captured when Charlestown surrendered in 1780. In February 1781 Clay was reassigned to the Fifth Virginia Regiment, but the unit existed only on paper and was ultimately dissolved. He was mustered out January 1783, entitled to more than 2,660 acres of western bounty land.[1]

Personal life

On December 4, 1788, Mathew Clay married Mary Williams of Pittsylvania County, who died on March 25, 1798, after giving birth to two sons and two daughters. Her gravestone names her father and husband, as well as a daughter Sally and a son Joseph, whereas Clay's will named his children as Joseph, Martha and Amanda Anne.[3] Matthew's daughter Mary was a victim of the Richmond Theatre fire of 1811.[citation needed] Clay remarried, to Ann Saunders of Buckingham County, who bore one daughter before dying on July 10, 1806.[1] As indicated by his will discussed below, Clay may also have had children out of wedlock, and directed his sons who were his executors to provide for three girls and one boy when they reached legal age for their gender.

Career

Summarize

Perspective

Immediately after the Revolutionary War, Clay worked in Richmond, as a clerk for the state solicitor general. His brothers Charles Clay and Green Clay both won election to and served in the Ratification Convention of 1788, where they opposed ratification of the federal constitution unless a Bill of Rights was added. Then Mathew Clay moved to Pittsylvania County to farm a land he inherited from a brother. Clay would both farm and practice law there for the rest of his life.[1] His home was near Chestnut Level.

Pittsylvania County voters first elected Clay to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1790, then re-elected him four times as one of their representatives in the Virginia House of Delegates (through 1794).[4] In 1790, in addition to service on the Committee of Propositions and Grievances, Clay became a member of a commission to improve the upper Roanoke River to permit commercial navigation. The next year, Clay headed a commission to determine whether to remove dams on the Bannister River to permit upstream fish migration (the harvest of shad, a large herring being important both as subsistence and for sale in the era). Also as a member of the Committee on Religion in 1791, Clay voted for a compromise (that failed to pass) which would have allowed the Episcopal Church to retain glebe lands (for the support of the minister and poor people of the parish, his brother Charles Green having been rector of St. Anne's Parish in Albemarle County before abandoning the ministry to farm in Bedford County). Clay also supported expanding suffrage to all white men who either owned property or could be forced to bear arms for the community, basing his argument on fairness. Clay had a combative debating style, and in one legislative argument in the 1791 session, accused Pittsylvania's other delegate of improprieties (but later apologized formally to the House for his conduct).[1] After losing his first attempt to unseat incumbent Congressman Isaac Coles (in 1793), Clay succeeded in the 1796 election, in part by attacking Coles for marrying an Englishwoman rather than a Virginia girl.[5][1] Clay won the post as a Democratic-Republican and was re-elected to the Fifth and to the seven succeeding Congresses, serving from March 4, 1797, to March 3, 1813, despite redistricting, and some difficulties in arriving early enough to secure appointment to the most influential committees. Thus, Clay served on the Committee of revised and Unfinished Business, and on the Committee of Elections (becoming its ranking member in 1809), as well as on the Committee on Militia (becoming its chairman in the Tenth Congress). Although initially a Jeffersonian Republican who opposed the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1803 and repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801, Clay later favored James Monroe over James Madison in 1808, only reluctantly agreeing that Monroe should not formally run and risk splitting the party. Clay also became known for his devotion to states' rights and strict interpretation of the Constitution, which sometimes allied him with Jefferson's opponents such as John Randolph of Roanoke and John Taylor of Caroline.[1] He was also one of six Democratic-Republican representatives to vote against the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[6]

Clay lost his reelection campaign in a primary in 1813 (to fellow Republican John Kerr, who had raised an unsuccessful challenge in 1811), so Clay did not attend the Thirteenth Congress. His refusal to vote in favor of the Declaration of War against Great Britain in June 1812 (Clay abstained on the vote, one of only two Virginia Republicans who declined to vote for the Declaration) proved unpopular with his constituents and contributed to his defeat, as did local factionalism and personal differences.[7] Clay won back his seat in the April 1815 (but was never sworn into the Fourteenth Congress), but died suddenly at Halifax Court House, while returning home from Richmond.[1]

Matthew Clay was one of the original trustees (in 1793) of the then unincorporated town of Danville. The others were Thomas Tunstall, William Harrison, John Wilson, Thomas Fearne, George Adams, and Thomas Smith.[citation needed]

Death and legacy

Clay died at Halifax Court House on May 27, 1815, while returning home from Richmond. Interment was probably in his family's burial vault (with his first wife and at least one child) in Pittsylvania County. When he died, Clay owned more than 3,000 acres in Kentucky, more than 1800 acres and at least thirteen slaves in Pittsylvania County. His will also directed his two sons (as his executors) to give a fourteen-year-old boy named William Penn a horse, bridle, saddle, clothes and $1000 when he reached 21 years old. Also to emancipate three mixed-race girls then about eight years old when they reached 18 years old and to give each clothes, $500 and transportation out of Virginia.[1]

Elections

- 1797; Clay was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives unopposed.

- 1799; Clay was re-elected defeating Federalist Isaac Coles.

- 1801; Clay was re-elected unopposed.

See also

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.