Margaret Sanger

American birth control activist and nurse (1879–1966) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Margaret Sanger (/ˈsæŋər/; née Higgins; September 14, 1879 – September 6, 1966) was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. She opened the first birth control clinic in the United States, founded Planned Parenthood, and was instrumental in the development of the first birth control pill. Sanger is regarded as a founder and leader of the birth control movement.

Margaret Sanger | |

|---|---|

Sanger in 1936 | |

| Born | Margaret Louise Higgins September 14, 1879 Corning, New York, U.S. |

| Died | September 6, 1966 (aged 86) Tucson, Arizona, U.S. |

| Other names | Margaret Sanger Slee |

| Occupation(s) | Social reformer, sex educator, writer, nurse |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives |

|

In the early 1900s, contraceptives, abortion, and even birth control literature were illegal in much of the U.S. Working as a nurse in the slums of New York City, Sanger often treated mothers desperate to avoid conceiving additional children, many of whom had resorted to back-alley abortions. Sanger was a first-wave feminist and believed that women should be able to decide if and when to have children, leading her to campaign for the legalization of contraceptives. As an adherent of the eugenics movement, she argued that birth control would reduce the number of unfit people and improve the overall health of the human race. She was also influenced by Malthusian concerns about the detrimental effects of overpopulation.

To promote birth control, Sanger gave speeches, wrote books, and published periodicals. Sanger deliberately flouted laws that prohibited distribution of information about contraceptives, and was arrested eight times. Her activism led to court rulings that legalized birth control, including one that enabled physicians to dispense contraceptives; and another – Griswold v. Connecticut – which legalized contraception, without a prescription, for couples nationwide.

Sanger established a network of dozens of birth control clinics across the country, which provided reproductive health services to hundreds of thousands of patients. She discouraged abortion, and her clinics never offered abortion services during her lifetime. She founded several organizations dedicated to family planning, including Planned Parenthood and International Planned Parenthood Federation. In the early 1950s, Sanger persuaded philanthropists to provide funding for biologist Gregory Pincus to develop the first birth control pill. She died in Arizona in 1966.

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Sanger's parents were Irish Catholics who separately emigrated from Ireland. Her father, Michael Hennessey Higgins, immigrated to Canada with his family, then moved to the U.S. at the age of 14, and joined the Union army in the Civil War as a drummer at 15. Upon leaving the army, he studied medicine and phrenology but ultimately became a stonecutter.[2][3] Her mother, Anne Purcell Higgins, immigrated to the U.S. with her family during the Great Famine.[2] Anne and Michael were married in 1869.[2]

Sanger was born Margaret Louise Higgins September 14, 1879 in Corning, New York. She spent her early years in a bustling household, under the influence of her father, who was a free-thinker, a socialist, and an agnostic.[4][5] In 22 years, Anne Higgins conceived 18 times, and gave birth to 11 live babies. She died at the age of 50, when Margaret was 19 years old.[2][b]

With financial help from two elder sisters, Margaret Higgins attended the Hudson River Institute at Claverack College from 1896 to 1900, then nursing school at White Plains Hospital from 1900 to 1902.[8] After graduating as a nurse, she married architect William Sanger in 1902. Although she suffered from tuberculosis, she settled down to a quiet life in Hastings-on-Hudson and had three children.[9]

Woman rebel

Summarize

Perspective

In 1911, after a fire destroyed their home, the Sangers abandoned the suburbs for a new life in New York City. Margaret Sanger worked as a nurse, making house calls in the slums of the East Side, while her husband worked as an architect and artist. The couple socialized with the bohemian community of Greenwich Village, including local intellectuals, left-wing artists, socialists and social activists, such as John Reed, Upton Sinclair, Mabel Dodge, and Emma Goldman. Sanger and her husband embraced socialism; Margaret joined the Women's Committee of the Socialist Party of New York and took part in the labor actions of the Industrial Workers of the World, including the 1912 Lawrence textile strike and the 1913 Paterson silk strike.[11][12][13]

Working as a nurse, Sanger visited many working-class immigrant women in their homes; many of them underwent frequent childbirth, miscarriages, and self-induced abortions.[14] Availability of contraceptive information was limited, due to the Comstock Act, a federal anti-obscenity law which prohibited – among other things – mailing contraceptives, or even information about contraception.[15] In 1913, she visited public libraries, searching for publications that instructed women how to avoid conception, but she found none.[16]

The hardships women faced were epitomized in a story that Sanger often recounted in her speeches: while working as a nurse, she was called to the apartment of a woman, "Sadie Sachs", who had a severe sepsis infection due to a self-induced abortion. Sadie begged the attending doctor to tell her how she could prevent this from happening again. The doctor laughed and said "You want your cake while you eat it too, do you? Well it can't be done. I'll tell you the only sure thing to do .... Tell Jake to sleep on the roof [abstain from sex]." A few months later, Sanger was called back to Sadie's apartment and found that Sadie had attempted yet another self-induced abortion; she died shortly after Sanger arrived. Sanger would sometimes end the story by saying, "I threw my nursing bag in the corner and announced ... that I would never take another case until I had made it possible for working women in America to have the knowledge to control birth."[17][18]

The Sadie Sachs episode was described by Sanger as the origin of her commitment to spare women from dangerous and illegal abortions.[19] Sanger opposed abortion, not on religious grounds, but as a societal ill and public health danger, which would disappear, she believed, if women were able to prevent unwanted pregnancy.[20]

Searching for a way to share her ideas with the public, she wrote two columns for the New York Call socialist magazine: What Every Mother Should Know (1911–12) and What Every Girl Should Know (1912–13).[21] The columns gave advice to women and girls on love, masturbation, and sex; and emphasized the distinction between sex and love.[22][23][24] By the standards of the day, Sanger's articles were extremely frank in their discussion of sexuality, and many New York Call readers were outraged by them. Other readers, however, praised the series for its integrity and candor.[24] Both series were later published in book form.[23]

Sanger's political interests, her emerging feminism, and her nursing experience led her to believe that only by liberating women from the risk of unwanted pregnancy would fundamental social change take place. In 1914, she undertook a decades-long campaign to free women, starting with The Woman Rebel, an eight-page monthly newsletter that used the slogan "No Gods, No Masters."[25][c] The newsletter contained articles about a variety of progressive subjects, including contraception, and was designed to challenge governmental censorship of contraceptive information through confrontation.[26][d] The Woman Rebel helped popularize the term "birth control", which was selected by Sanger and fellow activists as a more candid alternative to euphemisms then in use, such as "family limitation".[28][29][e]

Sanger became estranged from her husband in 1913, and their divorce was finalized in 1921.[31]

Year as an outlaw

Summarize

Perspective

Sanger's first obstacle to educating women about contraception was the Comstock Act, which banned dissemination of information about contraception. Her strategy was to deliberately violate the Act, hoping that the confrontation would eventually lead to amendment of the law.[33][34] Throughout 1914, she attempted to mail copies of the monthly The Woman Rebel newsletter.[f] Postal authorities intercepted five of its seven issues, but Sanger continued publication.[36][37] In August that year, Sanger was finally arrested for sending The Woman Rebel through the postal system.[38]

While awaiting trial, she wrote a 16-page pamphlet, Family Limitation, which detailed several contraceptive methods, discussed marriage and sex, and chided husbands who – after sex – fell asleep without bringing their wife to a climax.[39][40][41] Fearing arrest, several printers refused to print the pamphlet; she finally found a socialist printer willing to undertake the job, and he resorted to printing it secretly, at night.[42] The pamphlet was very popular: 100,000 copies were printed of its first edition, it went through 18 editions, and it was translated into a dozen languages.[40]

Facing imprisonment if she went to trial, she fled to Canada, where fellow activists forged a passport that permitted her to sail to England in early November.[43][g] Sanger spent most of her self-imposed exile in England, where contact with British Malthusians – such as Charles Vickery Drysdale and Bessie Drysdale – helped refine her socioeconomic justifications for birth control. She shared the concern of Malthusians that overpopulation led to poverty, famine, and war.[45] She would return to Europe in 1922 to attend the Fifth International Neo-Malthusian Conference – where she became the first woman to chair a session;[46] and she organized the Sixth International Neo-Malthusian and Birth-Control Conference that took place in New York in 1925.[47][48] Overpopulation would remain a concern of hers for the rest of her life.[45]

During her stay in England, she was profoundly influenced by British physician Havelock Ellis – author of the multi-volume Studies in the Psychology of Sex.[49][50] Under his tutelage, she expanded her birth control strategy to incorporate the additional benefit of stress-free, enjoyable sex; and came to adopt his view of sexuality as a powerful, liberating force.[51][52][53] While abroad, Sanger met with several Spanish anarchists, including activist Lorenzo Portet, with whom she had a passionate affair.[54][h]

News reports from America signaled to Sanger that support for birth control was increasing, so she returned from England in October 1915 to face trial. Shortly before the December trial, her five-year-old daughter, Peggy, died of pneumonia she caught while at a boarding school.[56][i] Sanger was offered a plea bargain, but refused, because she wanted to use the trial as a forum to advocate for the right of women to control their own bodies.[57] The prosecutor dropped the charges because he did not want to turn Sanger into a martyr.[58][59]

Early in 1915, an undercover representative of anti-vice politician Anthony Comstock asked Sanger's estranged husband, William, for a copy of Family Limitation, and William obliged. William was tried and convicted, spending thirty days in jail while attracting interest in birth control as an issue of civil liberty.[60][61][62]

The start of a movement

Summarize

Perspective

Some European countries had more liberal policies towards contraception than the United States. When Sanger visited a Dutch birth control clinic in 1915, she encountered diaphragms and became convinced that they were a more effective means of contraception than the suppositories and douches that she had been distributing back in the United States.[64] Diaphragms were generally unavailable in the United States due to the Comstock Act, so Sanger and others began importing them from Europe, in defiance of United States law.[65]

On October 16, 1916, Sanger opened a family planning and birth control clinic – the first in the United States – in the Brownsville neighborhood of the Brooklyn borough of New York City.[66][j] She was unable to find a physician to join the staff, so she turned to her sister, Ethel Byrne (a nurse), to fill the medical role.[68][69][k] Nine days after the clinic opened, Sanger was arrested for giving a birth control pamphlet to an undercover policewoman.[70] After she bailed out of jail, she continued assisting women in the clinic until the police arrested her a second time.[71][72] The clinic closed permanently after one month of operation, when the police forced the landlord to evict Sanger.[72]

Sanger and her sister were charged with distributing contraceptives in violation of New York state law. They went to trial on 29 January 1917.[73][74] Byrne was convicted and sentenced to 30 days in a workhouse, where she went on a hunger strike. She was force-fed, the first woman hunger striker in the U.S. to be so treated.[75] After ten days – when Sanger pledged that Byrne would never break the law – her sister was pardoned.[76] Sanger was also convicted; the trial judge was not persuaded by Sanger's argument that women had the right to enjoy sex without worrying about conceiving an unwanted child.[77] Sanger was offered a more lenient sentence if she promised not to break the law again, but she refused and said: "I cannot respect the law as it exists today."[78][79] Against the wishes of her attorney, she chose a thirty-day sentence in a workhouse, rather than a $5,000 fine.[79][80]

An initial appeal was rejected, but in a subsequent court proceeding in 1918 (after Sanger had served her sentence) the birth control movement secured a major victory when the New York Court of Appeals (New York's highest court) issued a ruling which allowed physicians in New York to dispense contraceptives.[81][82][l] The publicity surrounding Sanger's arrest, trial, and appeal sparked birth control activism across the United States, and generated momentum for the birth control movement.[84][85]

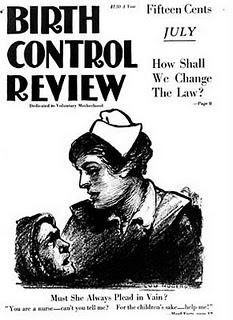

In February 1917, Sanger began publishing the periodical Birth Control Review, serving as its editor until 1929. The magazine was published monthly until 1940.[86]

In her 1920 book Woman and the New Race, Sanger framed her fight for birth control in the context of history, psychology, and feminism.[87][88][89] She wrote that male-dominated institutions, such as the church and state, have prohibited birth control throughout history – leading women to have too many children, too closely spaced. This, in turn, was a direct cause of mental distress and social pathology, and prevented women from full expression of their "feminine spirit". Sanger asserted that women have always fought back against this oppression through secretive use of abortion, contraception, or infanticide.[90] She believed that these efforts to limit family size were a manifestation of women's desire for freedom, writing:

"A free race cannot be born of slave mothers. A woman cannot choose but give a measure of that bondage to her sons and daughters. No woman can call herself free who does not own and control her body. No woman can call herself free until she can choose consciously whether she will or will not be a mother."[90][91]

Sanger had a long-term, though infrequent, love affair with the novelist H. G. Wells from 1920 until his death in 1946.[92] In 1922, she married her second husband, businessman James Noah H. Slee.[93]

Organizing

Summarize

Perspective

After World War I, Sanger continued to be frustrated by the inverted priorities of charities: they provided free obstetric and post-birth care to indigent women, yet failed to offer birth control or assistance in raising the children. She wrote: "The poor woman is taught how to have her seventh child, when what she wants to know is how to avoid ... her eighth."[95] Sanger saw a societal need to limit births by those least able to afford children: the affluent and educated already limited their childbearing, yet the poor and uneducated lacked access to contraception and information about birth control.[96]

Support from wealthy donors in the early 1920s enabled Sanger to expand her reach beyond local, small-scale activism, and allowed her to organize the American Birth Control League (ABCL).[72][97] The founding principles of the ABCL were:

"We hold that children should be (1) Conceived in love; (2) Born of the mother's conscious desire; (3) And only begotten under conditions which render possible the heritage of health. Therefore we hold that every woman must possess the power and freedom to prevent conception except when these conditions can be satisfied."[98]

The 1918 New York court decision had created an exception to the Comstock Act: contraceptives could be obtained, provided they were prescribed by a physician. To exploit this new loophole, in 1923 she established the Clinical Research Bureau (CRB) – a medical clinic with physicians on staff.[99][100][m] The CRB was the first birth control clinic in the U.S. that could dispense contraceptives directly to patients; and its staff of doctors, nurses, and social workers was entirely female.[102][n] The clinic received extensive funding from John D. Rockefeller Jr. and his family, who continued to make anonymous donations to Sanger's causes in subsequent decades.[103][104]

In 1922, soon after the formation of the ABCL, Sanger raised her international profile by traveling to Asia – giving speeches in Korea, Japan, and China.[105][106] She ultimately visited Japan seven times, working with feminist Shidzue Katō to promote birth control in Japan.[107][108]

As president of the ABCL, she chafed at bureaucratic interference from younger members of the board of directors.[109] Seeking more independence, she resigned from the presidency in 1928 and took full control of the CRB, renaming it the Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau (BCCRB). The two organizations, ABCL and BCCRB, continued to collaborate, but Sanger had complete control over the BCCRB's operations. This marked the beginning of a schism that would last until 1939.[110][111] By the 1930s, the BCCRB was serving over 10,000 patients per year, providing a range of gynecological services, conducting research, and training physicians and students.[111]

In 1925, Sanger's second husband, Noah Slee, contributed to the birth control movement by smuggling diaphragms into New York from Canada, hidden inside his company's cargo.[112] He then co-founded Holland-Rantos – the first manufacturer of legal diaphragms in the United States.[112]

Outreach and expansion

Summarize

Perspective

Sanger invested a great deal of effort in promoting birth control to the public. In 1916, she embarked on a cross-country lecture tour, speaking in dozens of cities – at churches, women's clubs, homes, and theaters. Her audience included workers, churchmen, liberals, socialists, scientists, and upper-class women.[114] She once lectured on birth control to the women's auxiliary of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) in Silver Lake, New Jersey.[115] Explaining her decision to address them, Sanger said that she was willing to speak to any group that would listen, if it helped promote the birth control cause. She described the experience as weird, and reported that she had the impression that the audience were dull, and so she spoke to them in the simplest possible language, as if talking to children.[115][p]

She wrote several books that had a nationwide impact in promoting the cause of birth control. Between 1920 and 1926, she sold 567,000 copies of Woman and the New Race and her 1922 book The Pivot of Civilization.[117] She wrote two autobiographies, both aimed at promoting birth control: Margaret Sanger: My Fight for Birth Control published in 1931; and Margaret Sanger An Autobiography published in 1938.[118]

During the 1920s, Sanger received hundreds of thousands of letters, many of them written in desperation by women begging for information on how to prevent unwanted pregnancies.[119][120] Many of the letters were printed in the monthly Birth Control Review, and 470 of these letters were compiled into the 1928 book, Motherhood in Bondage.[113]

Throughout the 1920s, Sanger and the ABCL expanded outward from their New York base by creating a network of birth control clinics across the country: Chicago (1924), Los Angeles (1925), San Antonio (1926), Detroit and Baltimore (1927), Cleveland, Newark, and Denver (1928), and Atlanta, Cincinnati, and Oakland (1929). These clinics were managed by local birth control advocates, and funded by local donors. Those that met Sanger's standards became official affiliates of the BCCRB.[121] A survey in 1930 showed that twelve of the clinics were, collectively, seeing a total of about 8,000 new patients per year.[122]

African American community

Summarize

Perspective

Women of all races and religions were served by Sanger's birth control clinics. Sanger did not tolerate bigotry among her staff, nor would she tolerate any refusal to work within interracial projects.[124] By 1929 about 12% of clinic patients listed Harlem as their address.[125]

In 1924, James H. Hubert, an African American social worker and the leader of New York's Urban League, asked Sanger to consider opening a clinic in an African American neighborhood.[126][127] In response, she established a clinic in the Columbus Hill neighborhood of New York City, but the clinic operated for only three months before closing due to low patient numbers.[125][126][q]

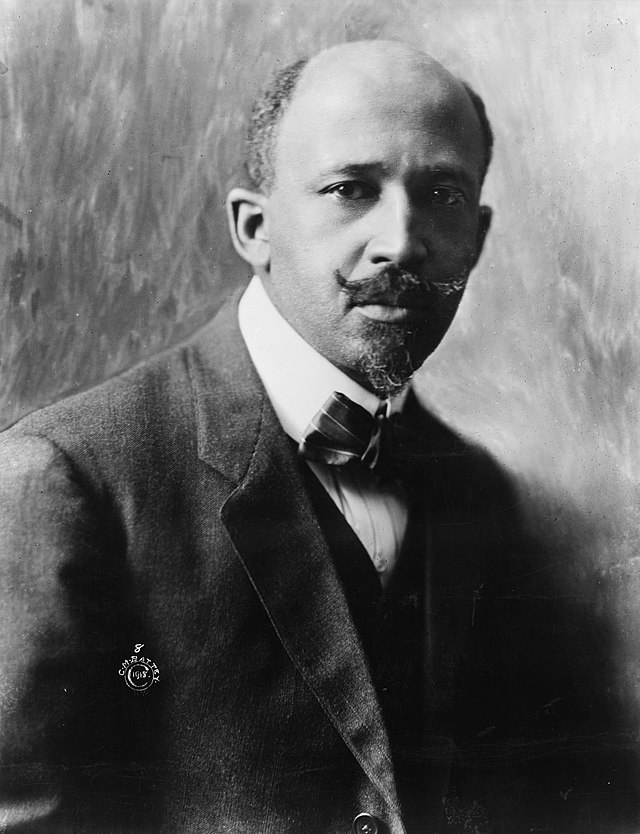

In 1929, Hubert approached Sanger again, this time suggesting a clinic in Harlem.[127][128][129] Sanger secured funding from the Julius Rosenwald Fund and opened the clinic in 1930.[130][131] The clinic was supported by an all-African American advisory board of 15 members and exclusively employed African American staff, including doctors, nurses, and social workers.[125][132][r] The clinic was publicized in the African American press as well as in African American churches, and it received the approval of W. E. B. Du Bois, the co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the editor of its magazine, The Crisis.[123][125][133][134] The clinic's clientele was about half African American and half white, and almost 3,000 patients visited the clinic in its first year and a half.[125] The Harlem clinic provided contraceptives and information to thousands of African American women until it closed in the mid-1940s.[127][131]

In June 1932, Sanger published a special issue of Birth Control Review titled "The Negro Number". Seven African American authors – including W.E.B Du Bois, George Schuyler, and Charles S. Johnson – contributed articles to the issue, providing reasons why contraception was beneficial for the African American community.[135][s]

During the 1920s and 1930s, Sanger toured the South and observed that African American women were neglected by the medical establishment, particularly in segregated areas.[136] In 1939, she worked with fellow birth control advocates Mary Lasker and Clarence Gamble to create the Negro Project, an effort to deliver information about birth control to impoverished African American people.[136][137] Sanger knew that the church played an important role in African American communities, so she advised Gamble (both Sanger and Gamble were white) on the importance of affiliating with African American ministers, writing:

"The ministers work is also important and also he should be trained, perhaps by the [Birth Control] Federation [of America] as to our ideals and the goal that we hope to reach. We do not want word to go out that we want to exterminate the Negro population and the minister is the man who can straighten out that idea if it ever occurs to any of their more rebellious members."[138]

When academic and activist Angela Davis, author of Women, Race and Class, analyzed that quote, she concluded that by 1939 the birth control movement had lost its progressive potential, and had evolved into a racist program of population control.[139][t][u] Davis' interpretation has been amplified by anti-abortion activists, leading many people to believe that Sanger was racist.[144][145] However, most scholars interpret the passage as Sanger's effort to prevent the spread of unfounded rumors about nefarious purposes, and they find no evidence that Sanger was a racist.[146][147][148][v][w]

After the Negro Project was initiated, management was handed to the Birth Control Federation of America. The project lasted from 1940 to 1943, but was unsuccessful: no new clinics were established, and participation rates remained low.[137]

Planned Parenthood

Summarize

Perspective

In 1929, Sanger formed the National Committee on Federal Legislation for Birth Control to lobby for legislation to overturn restrictions on contraception.[150][x] The lobbying did not produce results, so Sanger changed tack and in 1933 she ordered diaphragms from Japan to trigger a decisive battle in the courts.[150][152] The diaphragms were seized by the U.S. government, and Sanger's subsequent legal challenge to the confiscation led to a breakthrough 1936 court decision – United States v. One Package of Japanese Pessaries – which permitted physicians to dispense contraceptives nationwide.[153][154][y] This court victory motivated the American Medical Association to adopt contraception as a normal medical service (1937) and a key component of medical school curriculums (1942).[155][156][157]

Eager to take advantage of the One Package of Japanese Pessaries court ruling, which permitted birth control clinics across the country to begin dispensing contraceptives, leaders of the birth control movement took steps in 1937 to mend the rift between the ABCL and the BCCRB.[158] The two organizations merged in 1939 as the Birth Control Federation of America and, simultaneously, Sanger stepped down from her role as President/Chairman.[111][159][z] She no longer wielded the same power as she had in the early years of the movement, and in 1942 more conservative forces within the organization changed the name to Planned Parenthood Federation of America, a name Sanger objected to because she considered it too euphemistic.[160]

In the late 1940s, Sanger reduced her involvement in Planned Parenthood, and turned her attention to improving access to birth control globally. In 1948 she founded an exploratory committee, the International Committee on Planned Parenthood, which brought together representatives from birth control organizations in several countries around the world.[161] Four years later, in 1952, the committee evolved into the International Planned Parenthood Federation, which – as of 2025[update] – is the world's largest family planning NGO, consisting of 150 member associations working in 146 countries.[161][162][163] Sanger was the organization's first president and served in that role from 1952 to 1959.[161]

In the early 1950s, Sanger persuaded philanthropist Katharine McCormick to provide funding for biologist Gregory Pincus to develop the first birth control pill, which was eventually sold under the name Enovid.[164][165] Pincus recruited John Rock, a gynecologist at Harvard, to investigate clinical use of progesterone to prevent ovulation.[165][166] Pincus would later say that Sanger's role was essential in the development of the pill.[167]

In 1954, Sanger returned to Japan for her fourth visit, and gave a speech before a committee of the National Diet on the topic of "Population Problems and Family Planning".[107][108][168][aa]

Later life and death

Summarize

Perspective

In the late 1930s, Sanger began spending the winters in Tucson, Arizona, intending to play a less critical role in the birth control movement. She moved to Arizona full-time in 1943, after her husband died. In spite of her intention to retire, she remained active in the birth control movement through the 1950s.[171]

Sanger was silent about her personal religious beliefs through much of her life. At the time of her second marriage in 1922, Sanger was a socialist, bohemian atheist – according to biographer Ellen Chesler.[172][ab] When Sanger was 78 years old, she said she was Episcopalian.[173][ac]

Faced with declining health, Sanger moved into a convalescent home at age 83.[171] Before her death, the U.S. Supreme Court decided Griswold v. Connecticut, which struck down state laws prohibiting birth control in the United States.[175] The defendant in that case, Estelle Griswold, was the director of the Connecticut affiliate of Planned Parenthood.[176] A year before Sanger died, the Japanese government bestowed upon her the Order of the Precious Crown in recognition of her contributions to Japanese society.[107] She died of arteriosclerosis on September 6, 1966 in Tucson, Arizona, aged 86. Her funeral was held at St. Philip's in the Hills Episcopal Church in Tucson, followed a month later by a memorial service at St. George's Episcopal Church in Manhattan.[177] Sanger is buried in Fishkill, New York, next to her sister, Nan Higgins, and her second husband, Noah Slee.[178]

Views

Summarize

Perspective

Abortion

In the early 1900s, when Sanger started as an activist, abortion was illegal throughout the United States – though medically necessary abortions were permitted in some states.[180] Although abortion was illegal, it was widespread: in 1930, there were an estimated 800,000 illegal abortions performed in the U.S., resulting in 8,000 to 17,000 women's deaths from complications.[181][ad] Abortion frequency ranged from an estimated one abortion per five live births, to one abortion per 2.5 live births.[183][184] Despite the high rates of morbidity and death from back-alley abortions, there was no prospect of legalizing abortion in Sanger's era; serious efforts to legalize abortion did not begin in the U.S. until the mid-1950s.[185]

Sanger focused all her efforts on promoting contraception, rather than campaigning to make abortion legal. In her view, contraception was beneficial for many reasons: it was safe, simple, inexpensive, reduced the number of unwanted pregnancies, addressed overpopulation, and – most importantly – it eliminated the need for dangerous abortions.[186][187] Historian Peter Engelman notes an irony in Sanger's desire to end abortions: "... the birth control movement of the early 20th century, which evolved into a reproductive rights movement that vowed to make and keep abortion legal, set out initially to end the practice of abortion, which was then illegal."[188]

The majority of the educational material that Sanger produced was focused on contraception, and abortion was rarely mentioned. In her Family Limitation pamphlet, published in 1914, she wrote that every woman is entitled to make a choice of whether to have an abortion or not, and she suggested (incorrectly) that quinine could be used to induce abortion.[189][ae] That pamphlet was the only time she mentioned a technique for abortion.[189][af]

Sanger made many public statements discouraging abortion.[ag] When she opened her first birth control clinic in 1916, she distributed flyers to women, exhorting – in all capitals – "Do not kill, do not take life, but prevent."[179] After Pope Pius XI published Of Chaste Wedlock, an encyclical on sex, Sanger wrote a critical reply in 1932, which included:

"[Abortion] is an alternative that I cannot too strongly condemn. Although abortion may be resorted to in order to save the life of the mother, the practice of it merely for limitation of offspring is dangerous and vicious."[194]

Abortions were not performed at clinics managed by Sanger. For many years, staff were not even permitted to refer patients to physicians (in other facilities) for medically necessary abortions.[195] In 1932, sixteen years after the first clinic opened, Sanger authorized staff to refer patients to hospitals for medically necessary abortions.[196][ah] Planned Parenthood clinics would not offer abortions until 1970, several years after Sanger's death.[198]

Despite Sanger's public statements denouncing abortion for the purpose of limiting family size, historian Jean Baker suggests that Sanger privately felt that the procedure was ethical – but only as a last resort.[199]

Free speech

Advocates for birth control employed a variety of tactics. Some, such as Mary Dennett, preferred to work peacefully within the legislative system, and tried to amend the Comstock Act through lobbying. But Sanger chose to treat the undertaking as a battle for free speech, and repeatedly broke anti-obscenity laws, hoping to provoke arrest, which – she hoped – would lead to legal decisions in her favor.[201][202][203]

Her first brush with censorship came when she wrote a column, What Every Girl Should Know, for the New York Call. Her final article in that series, scheduled for publication on February 9, 1913, discussed syphilis and gonorrhea, so Comstock issued an order prohibiting publication. In response, Sanger and the Call replaced the column with a statement: "What Every Girl Should Know — NOTHING! — by order of the Post-Office Department".[23]

Sanger's views on free speech were expanded when Emma Goldman introduced Sanger to physician Edward Bliss Foote and lawyer Theodore Schroeder, co-founders of the Free Speech League, in New York.[204] Inspired by fellow free speech advocates, in 1914 she published The Woman Rebel with the express goal of triggering a legal challenge to the Comstock anti-obscenity laws banning dissemination of information about contraception.[205] The Free Speech League provided funding and advice to help Sanger with legal battles.[204]

One of the most formidable opponents to birth control in the 1920s was the Catholic Church, which often tried to prevent Sanger from giving speeches.[206][207][208] Catholics persuaded the Syracuse city council to ban Sanger from giving a speech in 1924; the National Catholic Welfare Conference lobbied against birth control; the Knights of Columbus boycotted hotels that hosted birth control events; the Catholic police commissioner of Albany prevented Sanger from speaking there; and several newsreel companies, succumbing to pressure from Catholics, refused to cover stories related to birth control.[209][210] Sanger turned some of the boycotted speaking events to her advantage by inviting the press, and the resultant news coverage often generated public sympathy for her cause.[211]

Numerous times in her career, local government officials prevented Sanger from speaking by shuttering a facility or threatening her hosts.[212] In 1929, city officials under the leadership of Boston's Catholic mayor James Curley threatened to arrest her if she spoke.[213][214] In response she stood on stage, silent, with a gag over her mouth, while Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr. read a statement from Sanger:

"... I have been gagged. I have been suppressed. I have been arrested numerous times. I have been hauled off to jail. Yet every time, more people have listened to me, more have protested, more have lifted up their own voices. As a pioneer fighting for a cause, I believe in free speech. As a propagandist I see immense advantages in being gagged. It silences me, but it makes millions of others talk and think the cause in which I live."[206][213][215]

Over the course of her career, Sanger was arrested several times for speaking or publishing prohibited information.[216]

Eugenics

Eugenics was one of many social reform movements that swept across America during the Progressive Era, which stretched from about 1890 to 1930. During the 1920s, when Margaret Sanger's work was gaining momentum, eugenics was a popular movement, promoted by major organizations, led by intellectuals and scientists, and funded by corporate foundations.[218][219][220]

Eugenic beliefs in the early 1900s covered a wide spectrum: at one extreme were those who overtly claimed the white race was superior, and wanted to reduce the population of certain other ethnicities.[221][222] At the other extreme were altruists who wanted to improve the health and well-being of the entire human race.[221][223][ai] Many eugenicists were somewhere between: they did not categorize ethnicities as superior or inferior; but their list of unfit traits included attributes such as illiteracy or low scores on IQ tests which – even if well-intended – often had the effect of targeting certain ethnicities.[221]

Sanger was surrounded by influential people who approved of eugenics, including close friends Havelock Ellis[228][229] and H. G. Wells,[92] and colleagues W. E. B. Du Bois[226][230] and Winston Churchill.[231][aj] Some associates of Sanger used eugenics to support their white supremacist beliefs, including Charles Davenport[233][234][235] and Lothrop Stoddard, a member of the KKK, and a founding board member of the ABCL who contributed an article to Birth Control Review.[236][237]

Sanger found common ground between eugenics and her birth control movement: both endeavors would benefit if contraception were legal and readily available.[238] From her perspective as an activist struggling to develop support for her cause, Sanger viewed the eugenics movement as scientific, respectable, growing, international, and popular.[238][239][240] Sanger adopted eugenics because it was an opportunity to advocate for the legalization of contraception – eugenics was a means to her end.[238][239][241][242] Whether she genuinely believed in eugenic principles is a matter of debate; several historians conclude that her belief was not sincere, and suggest that she joined with the eugenics movement simply to lend legitimacy to her birth control efforts.[238][242][243][244]

Her support of eugenics was first manifested in 1917, when she published an article on eugenics by Paul Popenoe in her periodical Birth Control Review.[245] From 1919 to 1921 she wrote several articles on the subject, leading to her 1922 book focused on eugenics, The Pivot of Civilization.[217]

Sanger's approach to eugenics

Sanger adopted the fundamental eugenic goal of reducing the number of unfit people. In that group, she included people who were insane, syphilitic, "paupers, morons, feeble-minded, mentally and morally deficient persons"; and included "reckless" people who were incapable of restraining themselves from having an excessive number of offspring.[246][247][ak]

To reduce the number of unfit children, Sanger initially emphasized contraceptives, which set her apart from mainstream eugenicists, who preferred sterilization.[238][250][251][al] However, when the U.S. Supreme Court decided that involuntary sterilization was legal in 1927, she began to endorse voluntary sterilization (in addition to contraception).[253] She also began to support involuntary sterilizations in limited circumstances: for parents who were incapable of managing their own fertility and were likely to produce disabled children.[249][254][255] About 60,000 Americans were sterilized involuntarily between 1927 and World War II.[256][am]

Sanger's approach to eugenics was heavily influenced by her feminism, which led her to deviate from mainstream eugenics in several ways:[217][257][258][259] She supported the right of fit parents to limit the size of their families; whereas mainstream eugenicists felt it was the duty of fit parents to have a large number of offspring.[251][260][an] And Sanger believed that mothers – with some exceptions – should individually regulate their family size; whereas mainstream eugenicists believed government mandates should be employed.[257][262][ao][ap]

Her eugenic proposals did not target specific ethnicities: instead, her goal was to improve the health of the whole human race by reducing the reproduction of those who were considered unfit.[266][267][268][aq] When she used the word "race" in the context of eugenics, the word invariably meant the entire human race, rather than a specific ethnicity; when she used the word "unfit" she meant an inherited defect, not an ethnicity.[246][266][270][ai] The consensus of scholars is that Sanger was not racist, but her collaboration with eugenicists indirectly assisted racist causes. Academic Dorothy Roberts, author of Killing the Black Body, wrote "Sanger did not tie fitness for reproduction to any particular ethnic group. It appears that Sanger was motivated by a genuine concern to improve the health of poor mothers she served rather than a desire to eliminate their stock."[266] Roberts' assessment is echoed by other scholars, including scholar Carole McCann,[271] historian Peter Engelman,[272] and biographer Ellen Chesler.[273]

Sanger had affiliated with eugenicists in the hope of gaining their support for her birth control movement – but her devotion was not reciprocated: the American Eugenics Society refused to accept any papers submitted by Sanger, most eugenicists ridiculed the birth control movement, and only a few would associate with her.[234][274] The reasons were that Sanger was a woman, she had no academic credentials, and she insisted that mothers should have the power to decide if and when to have children, which ran contrary to the mainstream eugenic policy that the state should order fit women to produce abundant offspring.[238][243][274][ar]

Legacy and honors

Summarize

Perspective

Sanger achieved her goal of improving the well-being of women around the world through family planning: contraception is now legal in the U.S., family planning clinics are commonplace, contraception is taught in medical schools, tens of millions of women have made use of Planned Parenthood services, and hundreds of millions of women around the globe have access to birth control pills.[277][278] As a result, Sanger is viewed today as an important first-wave feminist and a founder and leader of the birth control movement.[279][280][281]

Sanger's personal papers are held in two locations: the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College,[282] and the Library of Congress.[283] The papers were curated by the Margaret Sanger Papers Project, led by Esther Katz, which published them in four printed volumes.[284]

Several biographers have documented Sanger's life, including David Kennedy, whose 1970 book Birth Control in America: The Career of Margaret Sanger won the Bancroft Prize and the John Gilmary Shea Prize. Television films Portrait of a Rebel: The Remarkable Mrs. Sanger and Choices of the Heart: The Margaret Sanger Story have portrayed Sanger's life[285][286] as well as two graphic novels.[287][288]

Martin Luther King Jr. praised Sanger's work in his acceptance speech for the 1966 Margaret Sanger Award: "[Sanger] went into the slums and set up a birth control clinic, and for this deed she went to jail because she was violating an unjust law.... She launched a movement which is obeying a higher law to preserve human life under humane conditions.... Our sure beginning in the struggle for equality by nonviolent direct action may not have been so resolute without the tradition established by Margaret Sanger."[289][as]

Time magazine designated Sanger as one of the 100 most important people of the 20th century.[291] Between 1953 and 1963, Sanger was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize 31 times.[292] In 1957, the American Humanist Association named her Humanist of the Year.[293] There is a bust of Sanger in the National Portrait Gallery, which was a gift from Cordelia Scaife May.[294] Smith College awarded Sanger an honorary doctorate degree in 1949.[295] In 1966, Planned Parenthood began issuing its Margaret Sanger Awards annually to honor "individuals of distinction in recognition of excellence and leadership in furthering reproductive health and reproductive rights".[296][at] In 1981, Sanger was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[297] In 1993, the United States National Park Service designated the Margaret Sanger Clinic – where she provided birth-control services in New York in the mid-twentieth century – as a National Historic Landmark.[298] Government authorities and other institutions have memorialized Sanger by dedicating several landmarks in her name, including a room in Wellesley College's library,[299] and Margaret Sanger Square in New York City's Noho area.[276] There is a Margaret Sanger Lane in Plattsburgh, New York and an Allée Margaret Sanger in Saint-Nazaire, France.[300] Sanger, a crater in the northern hemisphere of Venus, is named after her.[301]

Attacks by anti-abortion activists

Since the legalization of abortion in 1973, Sanger has become a target of frequent attacks by opponents of abortion.[302][303][304][au] The attacks usually include falsehoods, and they often attribute quotes to Sanger that are either fabricated or presented out of context.[145][249][267][309][av] Common falsehoods are: she was a racist, she was a proponent of abortion, she was a Nazi sympathizer, or she supported the KKK.[235][267][311][312][aw] Another persistent falsehood is the claim that Sanger applied her birth control policies with the intention of suppressing the African American community.[313][ax]

Beginning in 2015, Planned Parenthood – hoping to improve relations with minority communities – took steps to distance itself from its founder: it removed Sanger's name from its annual awards, published an editorial in which it repudiated Sanger's advocacy of eugenics, and removed Sanger's name from its family planning clinic in Manhattan.[320][at] Essayist Katha Pollitt and Sanger biographer Ellen Chesner criticized Planned Parenthood for succumbing to pressure from the anti-abortion movement.[324][325]

Works

Books and pamphlets

- Sanger, Margaret (1912) [1911]. What Every Mother Should Know. Retrieved December 15, 2024. Originally published in 1911 as a column in the New York Call. The column was based on a set of lectures Sanger gave to groups of Socialist party women in 1910–1911. Multiple editions were published in book form starting in 1912 by Max N. Maisel and Sincere Publishing, with the title What Every Mother Should Know, or how six little children were taught the truth.

- —— (1914). Family Limitation (First ed.). Eighteen editions of this pamphlet were published, including:

• Family Limitation (Sixth ed.). 1917. Retrieved January 15, 2025.

• Family Limitation (Ninth ed.). 1919. Retrieved January 15, 2025.

• Family Limitation (Eighteenth ed.). 1931. Retrieved January 15, 2025.

- —— (1916) [1912-1913]. What Every Girl Should Know. Retrieved January 15, 2025. Originally published as a column in 1912-1913; published in book form in 1916.

- —— (1916a). The Fight for Birth Control. LCCN 2003558097. Retrieved January 15, 2025. Pamphlet.

- —— (1917). The Case for Birth Control: A Supplementary Brief and Statement of Facts. Modern art printing Company. OCLC 1132035. Retrieved January 15, 2025. Filed with court to support a legal battle.

- —— (1920). Woman and the New Race. Truth Publishing. OCLC 7301455. Retrieved January 15, 2025. Foreword by Havelock Ellis. Published in England with the title The New Motherhood.

- —— (1921). Debate on Birth Control. Haldeman-Julius Company. LCCN 2004563524. Retrieved January 15, 2025. Transcript of a debate between several prominent figures: Sanger, Theodore Roosevelt, Winter Russell, George Bernard Shaw, Robert L. Wolf, and Emma Sargent Russell.

- —— (1922). The Pivot of Civilization. Brentanos. Retrieved November 1, 2024. Entire book reprinted, with commentary and contemporary writings, in Sanger, Margaret; et al. (2001). Perry, M.W. (ed.). The Pivot of Civilization in Historical Perspective: The Birth Control Classic. Inkling Books. ISBN 9781587420085. Retrieved February 6, 2025.

- ——, ed. (1928). Motherhood in Bondage. Brentanos. LCCN 28028778. Retrieved January 15, 2025. A collection of letters women wrote to Sanger; many were initially published in Birth Control Review.

- —— (1931). My Fight for Birth Control. Farrar & Rinehart. LCCN 31028223. Retrieved January 15, 2025.

- —— (1938). Margaret Sanger An Autobiography. New York: W. W. Norton. Retrieved January 15, 2025. Republished starting in 1971 titled The Autobiography of Margaret Sanger. Dover. 2012. ISBN 9780486120836.

Collections

- Sanger, Margaret (2003). Esther Katz; Cathy Moran Hajo; Peter Engelman (eds.). The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 1: The Woman Rebel, 1900–1928. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252027376. OCLC 773147056.

- —— (2007). Esther Katz; Cathy Moran Hajo; Peter Engelman (eds.). The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 2: Birth Control Comes of Age, 1928–1939. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252031373.

- —— (2010). Esther Katz; Cathy Moran Hajo; Peter Engelman (eds.). The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 3: The Politics of Planned Parenthood, 1939–1966. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252033728.

- —— (2016). Esther Katz; Cathy Moran Hajo; Peter Engelman (eds.). The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 4: Round the World for Birth Control, 1920-1966. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252098802.

- "The Margaret Sanger Papers at Smith College". Smith College. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- "The Margaret Sanger Papers Project". Sponsored by New York University. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- "Margaret Sanger papers, 1900–1966". Library of Congress. Retrieved March 6, 2025.

Letters and articles

- Sanger, Margaret (February 1919). "Birth Control and Racial Betterment". Birth Control Review. 3 (2): 11–12. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- —— (March 1919b). "Why Not Birth Control Clinics in America?". American Medicine. 25: 164–167. ISSN 0898-6304. Retrieved January 10, 2025. Included as chapter 16 in Sanger's 1920 book Woman and the New Race.

- —— (1921b). "The Eugenic Value of Birth Control Propaganda". Birth Control Review. 5 (10): 5. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- —— (January 27, 1932). "The Pope's Position on Birth Control". The Nation. 135 (3473): 102–104. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved January 29, 2025.

- —— (May 27, 1934). "America Needs a Code for Babies". The Washington Herald. ISSN 1941-0662. Retrieved January 16, 2025.

- —— (December 10, 1939). "Letter from Margaret Sanger to Dr. C.J. Gamble". Letter to Clarence Gamble. Smith Libraries Exhibits. p. 2. Archived from the original on April 12, 2023. Retrieved December 13, 2024.

Periodicals

- The Woman Rebel – Seven issues published monthly from March 1914 to September 1914. Sanger was publisher and editor. Digital copies of all issues.

- Birth Control Review – Published monthly from February 1917 to 1940 (although some issues covered two or three months). Sanger was editor until 1929, when she resigned from the ABCL.[86] Digital copies of volumes 1 to 13 (1917 to 1929).

Speeches

- Sanger, Margaret (November 18, 1921a). "The Morality of Birth Control". Iowa State University Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- —— (1921–1922). "A Moral Necessity for Birth Control". Iowa State University Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- —— (March 30, 1925). "The Children's Era". Iowa State University Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- —— (April 16, 1929). "Ford Hall Forum Address". Iowa State University Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics. Retrieved February 20, 2025. Sanger's statement, read by Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr.

- —— (January 25, 1937). "Woman and the Future". Iowa State University Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.