Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Manned Maneuvering Unit

NASA astronaut propulsion unit From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

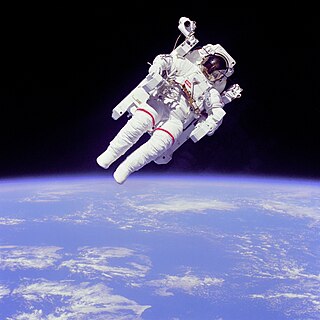

The Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) is an astronaut propulsion unit that was used by NASA on three Space Shuttle missions in 1984. The MMU allowed the astronauts to perform untethered extravehicular spacewalks at a distance from the shuttle. The MMU was used in practice to retrieve a pair of faulty communications satellites, Westar VI and Palapa B2. Following the third mission the unit was retired from use. A smaller successor, the Simplified Aid For EVA Rescue (SAFER), was first flown in 1994; it is intended for emergency use only.

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2011) |

Remove ads

Overview

Summarize

Perspective

The unit featured redundancy to protect against failure of individual systems. It was designed to fit over the life-support system backpack of the Space Shuttle Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU). When carried into space, the MMU was stowed in a support station attached to the wall of the payload bay near the airlock hatch. Two MMUs were carried on a mission, with the second unit mounted across from the first on the opposite payload bay wall. The MMU controller arms were folded for storage. When an astronaut backed into the unit and snapped the life-support system into place, the arms were unfolded.

To adapt to astronauts with different arm lengths, controller arms could be adjusted over a range of approximately 13 centimetres. The MMU was small enough to be maneuvered with ease around and within complex structures. With a full propellant load, its mass was 148 kilograms (326 pounds).

Gaseous nitrogen was used as the propellant for the MMU. Two aluminum tanks with Kevlar wrappings contained 5.9 kilograms of nitrogen each, enough propellant for a six-hour Extravehicular activity (EVA) depending on the amount of maneuvering done. The two propellent tanks had an initial charge on the ground prior to the mission allowing for Delta-v of 110 to 130 ft/sec. The tanks could be recharged in orbit to a minimum equivalent Delta-v of 72 ft/sec. For a nominal mass, translational acceleration was 0.3±0.05 ft/sec2 and rotational acceleration was 10.0±3.0 deg/sec2.[1]

There were 24 nozzle thrusters placed at different locations on the MMU. To operate the propulsion system, the astronaut used their fingertips to manipulate hand controllers at the ends of the MMU's two arms. The right controller produced rotational acceleration for roll, pitch, and yaw. The left controller produced translational acceleration for moving forward-back, up-down, and left-right. Coordination of the two controllers produced intricate movements in the unit. Once a desired orientation was achieved, the astronaut could engage an automatic attitude-hold function that maintained the inertial attitude of the unit in flight. This freed both hands for work.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

In 1966, the US Air Force developed an Astronaut Maneuvering Unit (AMU), a self-contained rocket pack very similar to the MMU. This was planned to be tested during Project Gemini on an EVA by Eugene Cernan on Gemini 9A on June 5, 1966. However, the test had to be cancelled because Cernan, tired and overheated, sweated so profusely that his helmet visor fogged before he could get to the AMU mounted on the back of the spacecraft. Astronauts did not learn how to work during EVA without tiring until the final Gemini 12 mission, but no AMU was carried on that flight. Since there was no real need for self-contained astronaut EVA flight in the Apollo and Skylab programs, the idea had to wait for the advent of the Space Shuttle program, though several maneuvering device designs were tested inside Skylab.

Active use in space

The MMU was used on three Shuttle missions in 1984. It was first tested on February 7 during mission STS-41-B by astronauts Bruce McCandless II and Robert L. Stewart. Two months later, during mission STS-41-C, astronauts James van Hoften and George Nelson attempted to use the MMU to capture the Solar Maximum Mission satellite and to bring it into the orbiter's payload bay for repairs and servicing. The plan was to use an astronaut-piloted MMU to grapple the SMM with the Trunion Pin Attachment Device (TPAD) mounted between the hand controllers of the MMU, null its rotation rates, and allow the Shuttle to bring it into the Shuttle's payload bay for stowage. Three attempts to grapple the satellite using the TPAD failed. The TPAD jaws could not lock onto Solar Max because of an obstructing grommet on the satellite not included in the blueprints for the satellite. This led to an improvised plan which nearly ended the satellite's mission. The improvisation had the MMU astronaut use his hands to grab hold of an SMM solar array and null the rates by a push from MMU's thrusters. Instead, this attempt induced higher rates and in multiple axes; the satellite was tumbling out of control and quickly losing battery life. SMM Operations Control Center engineers shut down all non-essential SMM subsystems and with a bit of luck were able to recover the SMM minutes before total failure. The ground support engineers then stabilized the satellite and nulled its rotation rates for capture with the orbiter's robotic arm, the Shuttle Remote Manipulator System (SRMS). This proved to be a much better plan. Their successful work increased the lifespan of the satellite.

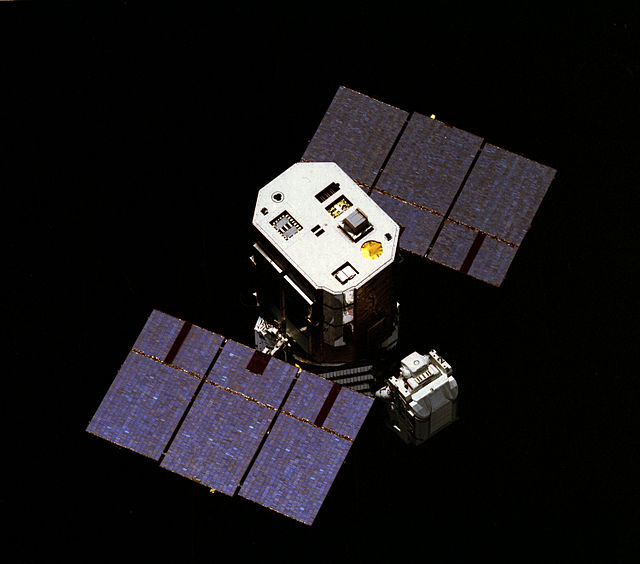

The final MMU mission was STS-51-A, which flew in November 1984. The propulsion unit was used to retrieve two communication satellites, Westar VI and Palapa B2, that did not reach their proper orbits because of faulty propulsion modules. Astronauts Joseph P. Allen and Dale Gardner captured the two satellites and brought them into the Orbiter payload bay for stowage and return to Earth.

Retirement

After a safety review following the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster, the MMU was judged too risky for further use and it was found many activities planned for the MMU could be done effectively with manipulator arms or traditional tethered EVAs.[2] NASA also discontinued using the Shuttle for commercial satellite contracts, and the military discontinued the use of the Shuttle, eliminating the main potential uses. Although the MMU was envisioned as a natural aid for constructing the International Space Station, with its retirement, NASA developed different tethered spacewalk approaches.

The two operational, flown flight units MMU No. 2 and No. 3 were stored by NASA in a clean room at Lockheed Martin in Denver through 1998. NASA transferred flight article No. 3 to the National Air and Space Museum in 1998, which now hangs suspended in the hall above Space Shuttle Discovery in the Udvar-Hazy Center annex.[3][4] Flight article No. 2 is on display at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. As of 2017, MMU No. 1 is on display in the Space Vehicle Mockup Facility at Johnson Space Center.

Remove ads

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads