Makar

Term from Scottish literature for a poet or bard From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A makar ( /ˈmækər/ ⓘ) is a term from Scottish literature for a poet or bard, often thought of as a royal court poet.

St Andrews Cathedral, St Andrews, now in ruins: one of Scotland's key buildings in the classic period of the Makars and a possible presence in some of Dunbar's spiritual works

Since the 19th century, the term The Makars has been specifically used to refer to a number of poets of fifteenth and sixteenth century Scotland, in particular Robert Henryson, William Dunbar and Gavin Douglas, who wrote a diverse genre of works in Middle Scots in the period of the Northern Renaissance.

The Makars have often been referred to by literary critics as Scots Chaucerians. In modern usage, poets of the Scots revival in the 18th century, such as Allan Ramsay and Robert Fergusson are also makars.

Since 2002, the term "makar" has been revived as the name for a publicly funded poet, first in Edinburgh, followed by the cities of Glasgow, Stirling and Dundee. In 2004 the position of Makar, was authorized by the Scottish Parliament.

Etymology

Middle Scots makar (plural makaris) is the equivalent of Middle English maker. The word functions as a calque (literal translation) of Ancient Greek term ποιητής (poiētēs) "maker; poet". The term is normally applied to poets writing in Scots although it need not be exclusive to Scottish writers. William Dunbar for instance referred to the English poets Chaucer, Lydgate and Gower as makaris.[1]

The Makars in history

Summarize

Perspective

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

The work of the Makar of the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries was in part marked out by an adoption in vernacular languages of the new and greater variety in metrics and prosody current across Europe after the influence of such figures as Dante and Petrarch and similar to the route which Chaucer followed in England. Their work is usually distinguished from the work of earlier Scottish writers such as Barbour and Wyntoun who wrote romance and chronicle verse in octosyllabic couplets and it also perhaps marked something of a departure from the medieval alliterative or troubador traditions; but one characteristic of poetry by the Makars is that features from all of these various traditions, such as strong alliteration and swift narration, continued to be a distinctive influence.

The first of the Makars proper in this sense, although perhaps the least Scots due to his education predominantly in captivity at the English court in London, is generally taken to be James I (1394–1437) the likely author of the Kingis Quair. Apart from other principal figures already named, writing by makars such as Richard Holland, Blind Hary and Walter Kennedy also survives along with evidence that suggests the existence of a substantial body of lost work. The quality of extant work generally, both minor and major, demonstrates a thriving poetic tradition in Scotland throughout the period.

Henryson, who is generally seen today as one of the foremost makars, is not known to have been a court poet, but the Royal Palace of Dunfermline, the city in which he was based, was one of the residences of the Stewart court.

A high point in cultural patronage was the Renaissance Court of James IV (1488–1513) now principally associated in literary terms with William Dunbar. The pinnacle in writing from this time was in fact Douglas's Eneados (1513), the first full and faithful translation of an important work of classical antiquity into any Anglic language. Douglas is one of the first authors to explicitly identify his language as Scottis. This was also the period when use of Scots in poetry was at its most richly and successfully aureate. Dunbar's Lament for the Makaris (c.1505) contains a leet of makars, not exclusively Scottish, some of whom are now only known through his mention, further indicative of the wider extent to the tradition.

Qualities in verse especially prized by many of these writers included the combination of skilful artifice with natural diction, concision and quickness (glegness) of expression. For example, Dunbar praises his peer, Merseir in The Lament (ll.74-5) as one

- That did in luf so lifly write, So schort, so quyk, of sentence hie...

- "That did in love so lively write, So short so quick, of sentence high..."

Some of the Makars, such as Dunbar, also featured an increasing incorporation of Latinate terms into Scots prosody, or aureation, heightening the creative tensions between the ornate and the natural in poetic diction.

The new plane of achievement set by Douglas in epic and translation was not followed up in the subsequent century, but later makars, such as David Lyndsay, still drew strongly on the work of fifteenth and early sixteenth century exponents. This influence can be traced right through to Alexander Scott and the various members of the Castalian Band in the Scottish court of James VI (1567–1603) which included Alexander Montgomerie and, once again, the king himself. The king composed a treatise, the Reulis and Cautelis (1584), which proposed a formalisation of Scottish prosody and consciously strove to identify what was distinctive in the Scots tradition.[2][3] The removal of the Court to London under James after 1603 is usually regarded as marking the eclipse of the distinctively Scottish tradition of poetry initiated by the Makars, but figures such as William Drummond might loosely be seen as forming a continuation into the seventeenth century.

The Makars have often been referred to by literary critics as Scots Chaucerians. While Chaucer's influence on fifteenth-century Scottish literature was certainly important, the makars drew strongly on a native tradition predating Chaucer, exemplified by Barbour, as well as the courtly literature of France.[4]

In the more general application of the term which is current today the word can be applied to poets of the Scots revival in the eighteenth century, such as Allan Ramsay and Robert Fergusson. In recent times, other examples of poets that have seemed to particularly exemplify the traditions of the makars have included Robert Garioch, Sydney Goodsir Smith, George Campbell Hay and Norman MacCaig among many others.[clarification needed]

Modern usage

Summarize

Perspective

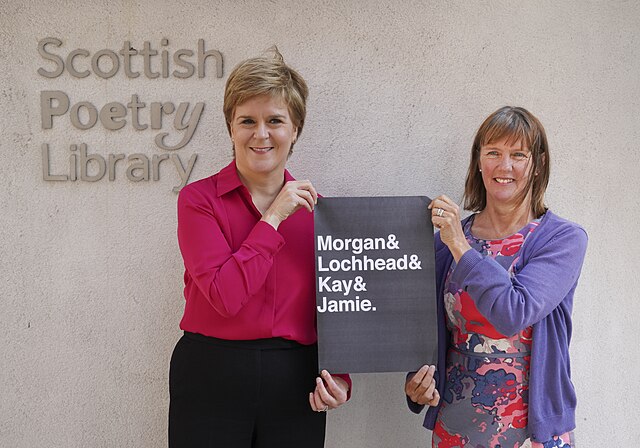

The Scots Makar

A position of national laureate, entitled The Scots Makar, was established in 2004 by the Scottish Parliament. The first appointment was made directly by the Parliament in that year when Edwin Morgan received the honour to become Scotland's first ever official national poet.[5][6] He was succeeded in 2011 by Liz Lochhead.[7] Jackie Kay was announced as the third holder of this post in 2016.[8] Before Kay was appointed, it was suggested that the role might now only be referred to as the National Poet for Scotland, because of concerns that the word makar had to be explained outside of Scotland.[9] Kay states that she argued for retaining the Makar name, which is still used.[10][11] In August 2021 Kathleen Jamie was announced as the fourth holder of the post.[12]

The city Makars

In 2002 the City of Edinburgh, Scotland's capital, instituted a post of makar, known as the Edinburgh Makar.[13] Each term lasts for three years and the first three incumbents were Stewart Conn (2002), Valerie Gillies (2005), and Ron Butlin (2008, 2011). The current incumbent (as of 2021) is Hannah Lavery.[14] The previous Edinburgh makars were Alan Spence.[15] and Shetlandic dialect writer and advocate Christine De Luca.

Other cities to create Makar posts include Glasgow (Liz Lochhead),[16] Stirling (Magi Gibson,[17] Laura Fyfe)[18] Aberdeen (Sheena Blackhall)[19] and Dundee (W.N. Herbert).[20]

Other uses

- American poet John Berryman uses the word in The Dream Songs #43 and #94.

- Makar is the name of a fictional character in the video game The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker, see The Wind Waker characters.

- Makar is a New York indie rock band formed in 2002 by singer/songwriters Mark Purnell and Andrea DeAngelis.[21]

- The Edinburgh Makars is an Amateur Drama Group founded in 1932 by Christine Orr, the well-known Scottish actress, broadcaster and playwright.[22]

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.