Madame Bovary (1949 film)

1949 film by Vincente Minnelli From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

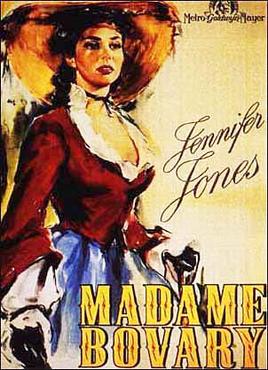

Madame Bovary is a 1949 American romantic drama, a film adaptation of the classic 1857 novel of the same name by Gustave Flaubert. It stars Jennifer Jones, James Mason, Van Heflin, Louis Jourdan, Alf Kjellin (billed as Christopher Kent), Gene Lockhart, Frank Allenby and Gladys Cooper.

| Madame Bovary | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Vincente Minnelli |

| Screenplay by | Robert Ardrey |

| Based on | Madame Bovary 1857 novel by Gustave Flaubert |

| Produced by | Pandro S. Berman |

| Starring | Jennifer Jones Van Heflin Louis Jourdan Christopher Kent Gene Lockhart Frank Allenby Gladys Cooper James Mason |

| Narrated by | James Mason |

| Cinematography | Robert H. Planck |

| Edited by | Ferris Webster |

| Music by | Miklós Rózsa |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 106 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2,076,000[2] |

| Box office | $2,016,000[2] |

It was directed by Vincente Minnelli and produced by Pandro S. Berman, from a screenplay by Robert Ardrey based on the Flaubert novel. The music score was by Miklós Rózsa, the cinematography by Robert H. Planck and the art direction by Cedric Gibbons and Jack Martin Smith.

The film was a project of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios and Lana Turner was set to star, but when pregnancy forced her to withdraw, Jones stepped into the title role. Production ran from mid-December 1948 to mid-March 1949 and the film premiered the following August.[1]

The story of a frivolous and adulterous wife presented censorship issues with the Motion Picture Production Code. A plot device which structured the story around author Flaubert's obscenity trial was developed to placate the censors. One famous sequence of the film is an elaborately choreographed ball sequence set to composer Miklós Rózsa's film score.

The film received an Academy Award nomination for Best Art Direction-Set Decoration in 1950 for Cedric Gibbons, Jack Martin Smith, Edwin B. Willis and Richard Pefferle.[3]

Plot

Summarize

Perspective

In an 1850s Paris courtroom, author Gustave Flaubert attempts to prevent the banning of his novel Madame Bovary. His accusers have described the book's title character as shocking and immoral. Flaubert counters with a narration of Bovary's story from his own realist perspective. Thus, we are introduced to 20-year-old Emma, a lonely woman who fantasizes a perfect life for herself. She falls in love with Dr. Charles Bovary. The two are married and move into a small house in Normandy. Emma re-decorates it lavishly, incurring much debt. Bemoaning her lack of social status, Emma tells Charles she wants a baby boy, someone not confined in accordance with Second French Empire’s repressive cultural norms. Instead, Emma gives birth to a girl, Berthe. She soon tires of her role as mother and leaves Berthe's upbringing to her nanny. Unhappy with her life, Emma embarks on a relationship with Leon Dupuis, but his mother induces him to move to Paris and enroll in law school.

After Charles fails to match her lofty expectations of "heroic country doctor", Emma succumbs to the advances of aristocrat Rodolphe Boulanger, who then abandons her. A heartbroken Emma attempts suicide, but Charles intervenes. She endures several months of severe depression, but eventually recovers. Sometime after, Emma and Charles attend an opera in nearby Rouen. There, they encounter Leon, who has returned from Paris. Leon brags of attaining his law credentials and earning lots of money. At first Emma rejects Leon's attempts to renew their affair, but she finally consents. When Emma returns home, she finds that the Bovarys' outstanding remodeling debts have come back to haunt them when their house is put up for sale to satisfy creditors. One of them offers to forgive Emma's debts in exchange for sex. She refuses, deciding instead to approach Leon for money. However, Leon admits he has no money to lend her, confessing he is only a law clerk. Finally, Emma turns to Rodolphe, but he flatly refuses to help. Rather than endure shame for what she has caused, Emma breaks into the village apothecary and swallows arsenic. Charles attempts to save her, but to no avail. Emma dies. The film then returns to Flaubert and the courtroom. In the end, it is decided the author's novel will not be blocked from publication.

Cast

- Jennifer Jones as Emma Bovary

- Van Heflin as Charles Bovary

- Louis Jourdan as Rodolphe Boulanger

- Christopher Kent as Léon Dupuis

- Gene Lockhart as J. Homais

- Frank Allenby as Lheureux

- Gladys Cooper as Mme. Dupuis

- John Abbott as Mayor Tuvache

- Henry Morgan as Hyppolite

- George Zucco as Dubocage

- Ellen Corby as Félicité

- Eduard Franz as Rouault

- Henri Letondal as Guillaumin

- Frederic Tozere as Pinard

- Paul Cavanagh as Marquis D'Andervilliers

- James Mason as Gustave Flaubert

- Esther Somers as Mme. Lefrançois

- Larry Simms as Justin

- Vernon Steele as Priest

Production

Lana Turner says it was the only film she turned down at MGM in her time there. She says she "got myself suspended. And it was a stinker!"[4]

Reception

Summarize

Perspective

Reviews from critics were mixed. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times was mostly positive, calling it a "faithful transcription" of the novel with an understanding of the protagonist "beautifully and tenderly put forth in the patient unfolding of the story which a cohort of talents has contrived." Crowther suggested, however, that Jones was "a little bit light for supporting the anguish of this classic dame."[5] Variety called the film "interesting to watch but hard to feel. It is a curiously unemotional account of some rather basic emotions and this failure to plumb beneath its characters lessens the broad, general appeal somewhat. However, the surface treatment of Vincente Minnelli's direction is slick and attractively presented." [6] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post called it a "persuasive picture", with Jones "bringing a depth of acting infrequently seen on the screen and a performance that far outweighs any of her previous ones."[7] Edwin Schallert of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "If one is patient with the slowness of 'Madame Bovary' he or she will find unique interest in this picture because in treatment and character it is well off the beaten path in Hollywood productions." However, Schallert found Jones to be "erratic in the quality of her presentation. She is pictorial on all occasions, surprisingly fine at times, very uncertain and wavering in her delineation at others."[8] Harrison's Reports published a negative review, calling the direction "heavy-handed" and the story "very unpleasant and slow-moving, and not one of the principal characters wins any sympathy, not even the heroine's ill-treated husband, a weakling who humbly accepts her sinning."[9] Philip Hamburger of The New Yorker called it "a dull-witted adaptation of the Flaubert classic. As interpreted by Miss Jones, Mme. Bovary could be Mme. X or Mme. Defarge, or Mme. Typhoid Mary, so amateurish and flaccid was her acting."[10]

According to MGM records the film earned $1,132,000 in the US and Canada and $884,000 overseas resulting in a loss of $910,000.[2][11]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – Nominated[12]

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.