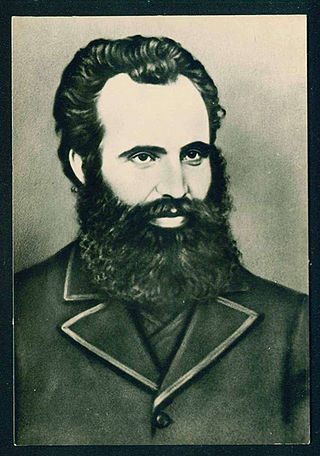

Lyuben Karavelov

Bulgarian writer and revolutionary From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Lyuben Stoychev Karavelov (Bulgarian: Любен Стойчев Каравелов; c. 1834 – 21 January 1879) was a Bulgarian writer, journalist, revolutionary and an important figure of the Bulgarian National Revival.[1][2] In his lifetime, he published many literary works. He was a leader of the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee.

Lyuben Karavelov | |

|---|---|

| Любен Каравелов | |

| |

| Born | Lyuben Stoychev Karavelov c. 1834 Koprivshtitsa, Ottoman Empire (now Bulgaria) |

| Died | 21 January 1879 Rousse, Bulgaria |

| Occupation(s) | Revolutionary, journalist, writer |

| Known for | Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee |

| Relatives | Petko Karavelov (brother) |

Life

Summarize

Perspective

Karavelov was born in Koprivshtitsa, Ottoman Empire (modern Bulgaria), in 1834,[3][4] as part of the Rum millet.[5] His father Stoycho Karavelov was a trader, while his mother Nedelya Doganova originated from a rich and educated family.[6] He began his education in a church school, but he moved to the school of Nayden Gerov and Yoakim Gruev.[7] His father sent him to study Greek at a Greek gymnasium in Plovdiv,[5] so that he can work as a trader.[8] While living with a Greek family there, he learned about the oppression of the Bulgarians by Greeks and Turks.[9] Karavelov studied weaving in 1853 and worked alongside his father.[7] In 1856, he worked as a trader's assistant in Istanbul. Having linguistic talent, he was more interested in literature and folklore than trade, so he decided to go to Odessa in the Russian Empire in the next year, where there was flourishing Bulgarian intellectual life.[5]

In 1857, Karavelov enrolled in the Faculty of History and Philology at the Moscow State University, with a scholarship from the Slavonic Committee,[6] where he fell under the influence of Russian revolutionary democrats Alexander Herzen and Nikolay Chernyshevsky.[5] Karavelov also begun opposing Tsarism, aristocracy, and the church.[10] He became a member of a Bulgarian society in Moscow in 1859, collecting literature, providing financial aid to Bulgarian young intellectuals and issuing the journal Fraternal Labor. He also contributed to the slavophile magazines Den (Day), Moskva (Moscow) and Moskovskie vedomosti (Moscow Gazette).[7] Karavelov also became closely associated with Russian Slavophiles, such as Ivan Aksakov and Mikhail Pogodin, who gave him funds to publish the 1861 Russian-language work Pamjatniki narodnago byta bolgar (Monuments of the Folk Culture of the Bulgarians).[9] However, after he was placed under police surveillance, he went to Belgrade in 1867 and worked as a journalist. Here, he fell under the influence of Pan-Slavism and became an ardent propagator of the ideology. In the same year, he also married Natalija Petrović, a Serbian activist and writer.[5] He went to Novi Sad and was arrested by the local authorities in connection with the murder of Serbian prince Mihailo Obrenović.[4] He was imprisoned in Budapest for seven months.[11] In 1869, he settled in Bucharest, working as a journalist.[5]

Karavelov became inspired by the works and ideas of a previous revolutionary Georgi Rakovski. He was among the founders of the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee (BRCC) and in 1872 became its chairman.[3] Together with Hristo Botev, he actively published revolutionary propaganda, alongside other prominent figures such as Panayot Hitov and Vasil Levski.[5] Karavelov edited BRCC's newspapers Freedom (Svoboda) and Independence (Nezavisimost), in collaboration with Botev.[12] Levski's execution by the Ottomans made him doubt the efficacy of BRCC's tactics. He left BRCC and began publishing Knowledge (Znanie), a literary and cultural magazine.[3] During the First Serbian–Ottoman War (starting from 1876) and the Russo-Turkish War between 1877 and 1878, he organized groups of Bulgarian volunteers.[4] In 1878, he returned to the Principality of Bulgaria, soon after its liberation. Karavelov died in Rousse, Bulgaria, on 21 January 1879 from tuberculosis.[3][5]

Views and works

Summarize

Perspective

Karavelov denied the continuity between modern Greeks and ancient Greeks.[13] He thought that the Greeks treated Bulgarians like "slaves" or "domesticated animals".[10] Per him, the Bulgarian medieval tsars did not have a Bulgarian identity. Karavelov also believed in the thesis that Slavs were autochthonous since indefinite time in Thrace, Macedonia and Danubian Bulgaria.[13] Karavelov described the Turkish character as being incapable of civilization: having no laws, no truth, and no humanity. He also promoted the concept of a Balkan Federation.[14] There was also strong anti-Turkish sentiment in his fictional works and at one point he wrote: "Anybody who will not agree that a Turk is more inhuman than a mad dog is a Turkophile."[9] Karavelov preferred Young Italy's form of civic nationalism. He saw the chorbadzhi as an obstacle for the national movement. In his newspapers, he had written: "The chief enemy of the Bulgarian nation is the Bulgarians themselves, i. e. our chorbadjii." and "Bulgaria will only be saved when the Turk, the chorbadjiya, and the bishop are hung from the same tree."[4] He described Ottoman rule as tyrannical, under which the Bulgarians were oppressed, and applied the same description for the Habsburg monarchy, which ruled over South Slavs and Romanians.[11]

He was an atheist.[4] While admiring the natural sciences, he was very critical of priesthood and superstition, and supported keeping scientific thought independent from political and religious power.[6] He thought that many social evils originated from organized religion. Karavelov published the short stories Vojvoda (Voivode, 1860), Turski pasha: zapiski na edna kalugerka (The Turkish Pasha: Notes of a Nun, 1866), and Machenik (The Martyr, 1870).[9] In 1867, he published his memoirs titled Iz zapisok bolgarina (From a Bulgarian's Notes) in the journal Russkij vestnik (Russian newspaper) and in 1868 a collection of shorter pieces under the title Stranicy iz knigi stradanij bolgarskago plemeni (Pages from the Book of Bulgarian Sufferings) in Russian.[9] He wrote the poems Njakoga i sega (Then and Now, 1872) and Kirilu i Metodiju (Cyril and Methodius, 1875).[9] Karavelov's other works include the short novels Old Time Bulgarians (Bulgarian: „Българи от старо време“; Bulgari ot staro vreme), and Mommy's Boy (Bulgarian: „Мамино детенце“; Mamino detentse).[3] His trilogy Otmashtenie (Revenge), Posle otmashtenieto (After Revenge), and Tuka mou e kraiat (This is the End), which he published in his newspaper Independence between 1873 and 1874, has been considered as the first Bulgarian historical novel. In his novels, he made an ideological division between Bulgarians and the Others. The Others being the Turks (external enemies), as well as the Greeks and treasonous Bulgarian aristocracy (internal enemies).[15]

He was also interested in ethnography and numismatics, seeking out old coins.[16] Karavelov had heard about 'the woman question' in the 1850s and 1860s in Russia.[6] In his 1869 short novel Kriva li e sadbata? (Is fate wrong?), published originally in Serbian as Je li kriva sudbina?,[9] he depicted woman not as an object or a slave, but as a rational and independent person of value to society, not merely there just to satisfy men.[6] He believed that because women lacked education, it made them incapable of working for the common good. In his opinion, few worthy sons were found among Bulgarians because there were few worthy mothers. While he praised women for organizing themselves, he also thought that women's associations would not be able to achieve anything unless men were members, arguing that such associations would be "like a body without a soul."[17] In his newspaper Freedom, he advocated that women "needed education like men: human, positive; a real education not a fashionable one."[6] After 1875, he viewed women's possible contributions to society more positively and advocated for female education.[17] In 1876, he published a series of articles titled "Za zhenskoto vospitanie" (On women's education), opposing ideas that women should be only be educated to perform manual labor and housekeeping, and that education should be fundamentally different between the sexes. He also opposed the double standards of men who approved of prostitution for their own pleasure but stigmatized women who did it to support themselves.[6] Karavelov praised the liberal political system of the United States, its educational system, and status of American women.[10]

Legacy

After his death, his complete works were published in eight volumes by his wife.[6] His younger brother Petko was a prominent figure in Bulgaria's political life in the late nineteenth century. Bulgarian politician Dimitar Blagoev described him as a "progressive liberal, whose views do not go further than political radicalism."[18] Karavelov has been ranked as the leading prose writer during the 1860s and 1870s in Bulgaria. American literary critic Charles Arthur Moser criticized his writing and style.[9] A translation of his work Is fate to blame? into Bulgarian was released in 1946.[15] A commemorative plaque in his honor was placed in the Bulgarian embassy in Belgrade in November 2024.[19]

References

Literature

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.