Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Currency union

Agreement involving states sharing a single currency From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

A currency union (also known as monetary union) is an intergovernmental agreement that involves two or more states sharing the same currency. These states may not necessarily have any further integration (such as an economic and monetary union, which would have, in addition, a customs union and a single market).

There are three types of currency unions:

- Informal – unilateral adoption of a foreign currency.[1]

- Formal – adoption of foreign currency by virtue of bilateral or multilateral agreement with the monetary authority, sometimes supplemented by issue of local currency in currency peg regime.

- Formal with common policy – establishment by multiple countries of a common monetary policy and monetary authority for their common currency.

The theory of the optimal currency area addresses the question of how to determine what geographical regions should share a currency in order to maximize economic efficiency.[2]

Remove ads

Advantages and disadvantages

Summarize

Perspective

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2019) |

Implementing a new currency in a country is always a controversial topic because it has both many advantages and disadvantages. New currency has different impacts on businesses and individuals, which creates more points of view on the usefulness of currency unions. As a consequence, governmental institutions often struggle when they try to implement a new currency, for example by entering a currency union.

Advantages

- A currency union helps its members strengthen their competitiveness on a global scale and eliminate the exchange rate risk.

- Transactions among member states can be processed faster and their costs decrease since fees to banks are lower.[3]

- Prices are more transparent and so are easier to compare, which enables fair competition.

- The probability of a monetary crisis is lower. The more countries there are in the currency union, the more they are resistant to crisis.

Disadvantages

- The member states lose their sovereignty in monetary policy decisions. There is usually an institution (such as a central bank) that takes care of the monetary policymaking in the whole currency union.

- The risk of asymmetric "shocks" may occur. The criteria set by the currency union are never perfect, so a group of countries might be substantially worse off while the others are booming.

- Implementing a new currency causes high financial costs. Businesses and also single persons have to adapt to the new currency in their country, which includes costs for the businesses to prepare their management, employees, and they also need to inform their clients and process plenty of new data.

- Unlimited capital movement may cause moving most resources to the more productive regions at the expense of the less productive regions. The more productive regions tend to attract more capital in goods and services, which might avoid the less productive regions.[4][5]

Remove ads

Convergence and divergence

Convergence in terms of macroeconomics means that countries have a similar economic behaviour (similar inflation rates and economic growth). It is easier to form a currency union for countries with more convergence as these countries have the same or at least very similar goals. The European Monetary Union (EMU) is a contemporary model for forming currency unions. Membership in the EMU requires that countries follow a strictly defined set of criteria (the member states are required to have a specific rate of inflation, government deficit, government debt, long-term interest rates and exchange rate). Many other unions have adopted the view that convergence is necessary, so they now follow similar rules to aim the same direction.

Divergence is the exact opposite of convergence. Countries with different goals are very difficult to integrate in a single currency union. Their economic behaviour is completely different, which may lead to disagreements. Divergence is therefore not optimal for forming a currency union.[6]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The first currency unions were established in the 19th century. The German Zollverein came into existence in 1834, and by 1866, it included most of the German states. The fragmented states of the German Confederation agreed on common policies to increase trade and political unity.

The Latin Monetary Union, comprising France, Belgium, Italy, Switzerland, and Greece, existed between 1865 and 1927, with coinage made of gold and silver. Coins of each country were legal tender and freely interchangeable across the area. The union's success made other states join informally.

The Scandinavian Monetary Union, comprising Sweden, Denmark, and Norway, existed between 1873 and 1905 and used a currency based on gold. The system was dissolved by Sweden in 1924.[7]

A currency union among the British colonies and protectorates in Southeast Asia, namely the Federation of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak, Singapore and Brunei was established in 1952. The Malaya and British Borneo dollar, the common currency for circulation was issued by the Board of Commissioners of Currency, Malaya and British Borneo from 1953 until 1967. Following the cessation of the common currency arrangement, Malaysia (the combination of Federation of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak), Singapore and Brunei began issuing their own currencies. Contemporarily, a currency reunion of these countries might still be feasible based on the findings of economic convergence.[8][9]

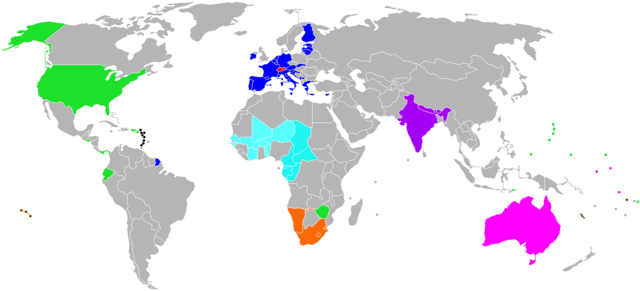

List of currency unions

Summarize

Perspective

Existing

Note: Every customs and monetary union and economic and monetary union also has a currency union.

![]() Zimbabwe is theoretically in a currency union with four blocs as the South African rand, Botswana pula, British pound and US dollar freely circulate. The US Dollar was, until 2016, official tender.[17]

Zimbabwe is theoretically in a currency union with four blocs as the South African rand, Botswana pula, British pound and US dollar freely circulate. The US Dollar was, until 2016, official tender.[17]

Additionally, the autonomous and dependent territories, such as some of the EU member state special territories, are sometimes treated as separate customs territory from their mainland state or have varying arrangements of formal or de facto customs union, common market and currency union (or combinations thereof) with the mainland and in regards to third countries through the trade pacts signed by the mainland state.[18]

Currency union in Europe

The European currency union is a part of the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union (EMU). EMU was formed during the second half of the 20th century after historic agreements, such as Treaty of Paris (1951), Maastricht Treaty (1992). In 2002, the euro, a single European currency, was adopted by 12 member states. Currently, the Eurozone has 20 member states. The other members of the European Union are required to adopt the euro as their currency (except for Denmark, which has been given the right to opt out), but there has not been a specific date set. The main independent institution responsible for stability of the euro is the European Central Bank (ECB). The Eurosystem groups together the ECB and the national central banks (NCBs) of the Member States whose currency is the euro. The European System of Central Banks (ESCB) is made up of the ECB and the national central banks of all Member States of the European Union (EU), regardless of whether or not they have adopted the euro. The Governing Board consists of the Executive Committee of the ECB and the governors of individual national banks, and determines the monetary policy, as well as short-term monetary objectives, key interest rates and the extent of monetary reserves.[19]

Planned

Disbanded

- between

Bahrain and

Bahrain and  Abu Dhabi using the Bahraini dinar

Abu Dhabi using the Bahraini dinar - between

Bahrain,

Bahrain,  Kuwait,

Kuwait,  Oman,

Oman,  Qatar and the

Qatar and the  Trucial States, using the Gulf rupee from 1959 until 1966

Trucial States, using the Gulf rupee from 1959 until 1966 - between

Aden,

Aden,  South Arabia,

South Arabia,  Bahrain,

Bahrain,  Kenya,

Kenya,  Kuwait,

Kuwait,  Oman,

Oman,  Qatar,

Qatar,  British Somaliland,

British Somaliland,  the Trucial States,

the Trucial States,  Uganda,

Uganda,  Zanzibar and

Zanzibar and  British India (later independent

British India (later independent  India) using the Indian rupee until 1974

India) using the Indian rupee until 1974 - between

Belgium and the

Belgium and the  Grand-Duchy of Luxemburg (Belgium-Luxembourg Economic Union) using the Belgian/Luxembourgish franc from 1921 to the Euro

Grand-Duchy of Luxemburg (Belgium-Luxembourg Economic Union) using the Belgian/Luxembourgish franc from 1921 to the Euro - between

British India and the

British India and the  Straits Settlements (1837–1867) using the Indian rupee

Straits Settlements (1837–1867) using the Indian rupee - between

Czech Republic and

Czech Republic and  Slovakia (briefly from January 1, 1993 to February 8, 1993) using the Czechoslovak koruna

Slovakia (briefly from January 1, 1993 to February 8, 1993) using the Czechoslovak koruna - between

Ethiopia and

Ethiopia and  Eritrea using the Ethiopian birr

Eritrea using the Ethiopian birr - between

France,

France,  Monaco, and

Monaco, and  Andorra using the French franc

Andorra using the French franc - between

Austria-Hungary and

Austria-Hungary and  Liechtenstein using the Austro-Hungarian krone

Liechtenstein using the Austro-Hungarian krone - between the Eastern Caribbean,

Jamaica,

Jamaica,  Barbados,

Barbados,  Trinidad and Tobago and

Trinidad and Tobago and  British Guiana using the British West Indies dollar

British Guiana using the British West Indies dollar - between the Eastern Caribbean,

Barbados,

Barbados,  Trinidad and Tobago and

Trinidad and Tobago and  British Guiana using the Eastern Caribbean dollar

British Guiana using the Eastern Caribbean dollar - between

Italy,

Italy,  Vatican City, and

Vatican City, and  San Marino using the Italian lira

San Marino using the Italian lira - between

Jamaica and the

Jamaica and the  Cayman Islands using the Jamaican pound and later Jamaican dollar

Cayman Islands using the Jamaican pound and later Jamaican dollar - between

Kenya,

Kenya,  Uganda, and

Uganda, and  Zanzibar using the East African rupee

Zanzibar using the East African rupee - between

Kenya,

Kenya,  Uganda, and

Uganda, and  Zanzibar (and later

Zanzibar (and later  Tanganyika) using the East African florin

Tanganyika) using the East African florin - between

Kenya,

Kenya,  Tanganyika and

Tanganyika and  Zanzibar (later merged as

Zanzibar (later merged as  Tanzania),

Tanzania),  Uganda,

Uganda,  South Arabia,

South Arabia,  British Somaliland and

British Somaliland and  Italian Somaliland using the East African shilling

Italian Somaliland using the East African shilling - Latin Monetary Union (1865–1927), initially between

France,

France,  Belgium,

Belgium,  Italy and

Italy and  Switzerland, and later involving

Switzerland, and later involving  Greece,[24]

Greece,[24]  Romania,

Romania,  Spain and other countries.

Spain and other countries. - between

Liberia and the

Liberia and the  United States using the United States dollar

United States using the United States dollar - between

Mauritius and

Mauritius and  Seychelles using the Mauritian rupee

Seychelles using the Mauritian rupee - between

Nigeria,

Nigeria,  the Gambia,

the Gambia,  Sierra Leone,

Sierra Leone,  the Gold Coast and

the Gold Coast and  Liberia using the British West African pound

Liberia using the British West African pound - between

Prussia and the North German states (1838–1857) using the North German thaler

Prussia and the North German states (1838–1857) using the North German thaler - between

Russia and the

Russia and the  former Soviet republics (1991–1993) using the Soviet ruble

former Soviet republics (1991–1993) using the Soviet ruble - between

Qatar and all the emirates of the

Qatar and all the emirates of the  United Arab Emirates, except Abu Dhabi using the Qatari and Dubai riyal

United Arab Emirates, except Abu Dhabi using the Qatari and Dubai riyal - between

Saudi Arabia and

Saudi Arabia and  Qatar using the Saudi riyal

Qatar using the Saudi riyal - between

Western Samoa and

Western Samoa and  New Zealand using the New Zealand pound

New Zealand using the New Zealand pound - Scandinavian Monetary Union (1870s until 1924), between

Denmark,

Denmark,  Norway and

Norway and  Sweden[24]

Sweden[24] - between the

Solomon Islands,

Solomon Islands,  Papua New Guinea and

Papua New Guinea and  Australia using the Australian dollar

Australia using the Australian dollar - between

Australia,

Australia,  Papua,

Papua,  New Guinea,

New Guinea,  Nauru,

Nauru,  the Solomon Islands, and

the Solomon Islands, and  the Gilbert and Ellice Islands using the Australian pound

the Gilbert and Ellice Islands using the Australian pound - between

Bavaria,

Bavaria,  Baden,

Baden,  Württemberg,

Württemberg,  Frankfurt, and

Frankfurt, and  Hohenzollern using the South German guilder

Hohenzollern using the South German guilder - between

Spain and

Spain and  Andorra using the Spanish peseta

Andorra using the Spanish peseta - between

Trinidad and Tobago and

Trinidad and Tobago and  Grenada using the Trinidad and Tobago dollar

Grenada using the Trinidad and Tobago dollar - between

Brunei,

Brunei,  Malaysia, and

Malaysia, and  Singapore (1953–1967) using the Malaya and British Borneo dollar

Singapore (1953–1967) using the Malaya and British Borneo dollar - between

Cambodia,

Cambodia,  Laos,

Laos,  Guangzhouwan,

Guangzhouwan,  Annam,

Annam,  Tonkin, and

Tonkin, and  Cochinchina (later

Cochinchina (later  Vietnam) between 1885 and 1952 using the French Indochinese piastre

Vietnam) between 1885 and 1952 using the French Indochinese piastre - between

South Africa,

South Africa,  South West Africa, and

South West Africa, and  Bechuanaland (later independent

Bechuanaland (later independent  Botswana) using the South African rand

Botswana) using the South African rand - between

Egypt,

Egypt,  Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, and

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, and  Mandatory Palestine (until 1926) using the Egyptian pound

Mandatory Palestine (until 1926) using the Egyptian pound - between

West Germany and

West Germany and  East Germany between 1 July 1990 and 3 October 1990, as part of a temporary, so-called "Monetary, Economic and Social Union" prior to German reunification.

East Germany between 1 July 1990 and 3 October 1990, as part of a temporary, so-called "Monetary, Economic and Social Union" prior to German reunification. - between what ultimately became the

Republic of Ireland and the

Republic of Ireland and the  United Kingdom, between 1928 and 1979. The Irish Pound was held at exactly the same value as Sterling for this period, although it was not accepted for payments in the UK.

United Kingdom, between 1928 and 1979. The Irish Pound was held at exactly the same value as Sterling for this period, although it was not accepted for payments in the UK. - Yen Bloc (between 1905 and 1945), between the

Empire of Japan, the

Empire of Japan, the  Korean Empire,

Korean Empire,  Manchukuo,

Manchukuo,  Mengjiang, the

Mengjiang, the  Wang Jingwei regime, and Japanese-occupied Southeast Asia prior to and during World War II.

Wang Jingwei regime, and Japanese-occupied Southeast Asia prior to and during World War II.

Never materialized

- proposed Pan-American monetary union – abandoned in the form proposed by Argentina

- proposed monetary union between the

United Kingdom and

United Kingdom and  Norway using the pound sterling during the late 1940s and early 1950s

Norway using the pound sterling during the late 1940s and early 1950s - proposed gold-backed, pan-African monetary union put forward by Muammar Gaddafi prior to his death

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads