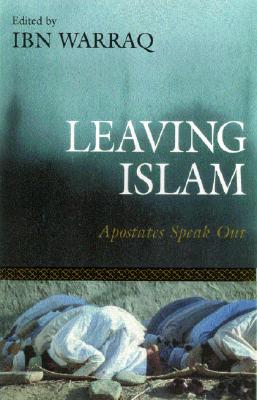

Leaving Islam

2003 book by Ibn Warraq From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Leaving Islam: Apostates Speak Out is a 2003 book, authored and edited by ex-Muslim and secularist Ibn Warraq, that researches and documents cases of apostasy in Islam. It also contains a collection of essays by ex-Muslims recounting their own experience in leaving the Islamic religion.[1][2]

| |

| Author | Ibn Warraq |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Islam |

| Publisher | Prometheus Books |

Publication date | 1 May 2003 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 320 pp |

| ISBN | 1-59102-068-9 |

| Preceded by | What the Koran Really Says |

| Followed by | Defending the West: A Critique of Edward Said's Orientalism |

Synopsis

Summarize

Perspective

Leaving Islam is divided into four parts, with a preface and five appendices.[3]

Part 1: Theory and practice of apostasy in Islam

The first part of the book presents an overview of the theological-juridical underpinnings of apostasy in Islam based upon the Qur’an, the hadiths and written opinions from classical schools of Islamic jurisprudence, as well as contemporary written pronouncements of Islamic jurists.

The next section presents the history of the application of Islamic jurisprudence on apostates, documenting notable cases from the early centuries of Islam, such as those of freethinkers Ibn al-Rawandi and Rhazes (865–925), or skeptical poets such as Omar Khayyam (1048–1131)[4] and Hafiz (1320–89), or Sufi (mystic) practitioners Mansur Al-Hallaj (executed in 922), As-Suhrawardi (executed in 1191), and the skeptic al-Ma'arri (973–1057).[4]

Part 2: Testimonies submitted to the ISIS website

Part 2 consists of numerous case studies, covering modern-day apostasies, and conversions-out-of-Islam trends throughout the world. These were submitted to the website of the Institute for the Secularisation of Islamic Society (ISIS), co-founded by Ibn Warraq.

Part 3: Testimonies of born Muslims: murtadd fitri

The third part contains testimonies of Muslim-raised apostates, including the ex-Muslim Ali Sina. According to Sina, it is no longer sufficient to simply not believe anymore, but "it is our duty to expose Islam, to write about Muhammad's depraved lifestyle, about his shameful acts and his foolish claims."[5] Many of the authors are from Iran, Pakistan and Bangladesh, where a strict version of Islam dominates society, even though the lingua franca isn't Arabic, and these authors only discovered the real meaning of the texts after reading translations of the Quran, hadith and other early Islamic writings when they moved to the West.[5]

Part 4: Testimonies of Western converts: murtadd milli

The last part is about people born in the West who were not raised as Muslims, but converted to Islam in later life, and then deconverted out of Islam again.

Appendices

The appendix "Islam on Trial: The Textual Evidence" cites, amongst other scriptural sources, Sahih Bukhari, Volume 9, Book 84, Number 57: "Whoever changes his religion, kill him."[2]

Author's rationale

Summarize

Perspective

On 24 June 2003, Ibn Warraq held a public lecture (in disguise, to protect his identity) in Cambridge, Massachusetts about the book and the context in which it was composed.[6]: 11:39 He cited several of his co-authors and other ex-Muslims who decided to leave the faith for a variety of reasons, but stated that these people rarely dared to speak out for themselves, and non-Muslims such as Western publishers often refused to grant them a platform out of fear.[6]: 13:52 Unlike himself however, Warraq said he was surprised that many co-authors, especially the women (whose stories he thought readers would "find the most moving"), were prepared to write their testimonies under their real names rather than pseudonyms.[6]: 34:16

In a July 2003 interview with The Religion Report on Australia's ABC Radio National, Warraq said he wrote Leaving Islam to support his claim that there were a large number of ex-Muslims and to encourage other Muslims to openly leave Islam. He also said his target audience with the book was not just Muslims but everyone.[7]

Aside from giving Muslim apostates a voice, Warraq also conveyed his idea that ex-Muslims should take the lead in criticising Islam and Islamism. As former Muslims, they have experienced Islam from within, and know it better than critics from outside, and perhaps can speak about it with more authority. To support this, Warraq compared 1930s Bolshevism and 1990s Islamism, and modern-day ex-Muslims to ex-communists from the 1930s, referencing Arthur Koestler's statement to his formerly fellow communists: "You hate our Cassandra cries and resent us as allies, but when all is said, we ex-Communists are the only people on your side who know what it's all about."[6]: 24:46

Reception

Summarize

Perspective

Some weeks before publication, a few writings taken from Leaving Islam were made available online on the website of Warraq's Institute for the Secularisation of Islamic Society. Reviewing these previews for Dutch daily newspaper Trouw, scholar of Islam Hans Jansen noted that, although "not all of the testimonies are written down in equally pretty English", he accepted this consequence of the World Wide Web being accessible around the globe and users with other native languages now able to communicate in unprecedented ways that censorship would previously prevent. "For the first time in history, Muslims will have unrestrained access to anti-Islamic polemics. The rule, applying in all Islamic countries, that only Islam may enter the marketplace of new religious ideas, has definitively come to an end due to the Internet, and Ibn Warraq."[8]

The New York Review of Books commented that Leaving Islam is "probably the first book of its kind — a compendium of testimonies from former Muslims about their estrangement from the Islamic faith." Finding the personal stories widely varying in quality ("from the tragic to the trite"), it remarked that the "long and illustrious history of Muslim doubt" in the book's first part was most informative.[9]

According to The Boston Globe, "Leaving Islam's stories make eye-opening reading."[10]

When a Dutch translation by Bernadette de Wit (with a foreword by Afshin Ellian) was published in 2008, de Volkskrant found the book "interesting, because it shows how the process of deconversion occurs in Muslim migrants." On the other hand, there was an apparent inconsistency in the authors' attitude towards the Abrahamic holy books. They agreed that both the Quran and the Bible described many atrocities and contained a lot of immoral commandments, but while modern Christians and Jews were praised for cherry-picking the good bits and ignoring the unethical parts or taking them as parables, the contributors of Leaving Islam tended to claim that modern Muslims who try to do the same are blind to what the texts literally say, and should stop believing in them altogether.[5]

Trouw journalist Eildert Mulder noted that the ex-Muslims' testimonies had a lot in common with those of ex-Christians. However, the latter usually focus on attacking the churches, or recounting how they suffered from their Christian upbringing; they rarely target the character of Jesus: "Criticism is restricted to the observation that one cannot walk on water, nor rise from the dead." In Leaving Islam, Mulder read that "Amongst deconverted Muslims, on the other hand, the aversion towards the prophet's personality is an important reason to break away from their religion. (...) The anger against Muhammad is enormous amongst apostates," especially concerning the oppression of women, human rights violations and mass murder. Although Warraq does discuss a few such cases in the book, Mulder criticised Warraq's website for featuring only ex-Muslim atheists and agnostics' excerpts from the book, and none from people who left Islam for another religion: "This website is not dedicated to people who have exchanged one type of irrationality for another." Mulder concludes that the books' contributors are "impressive, because these people have literally put their lives on the line."[4]

In a similar book, The Apostates: When Muslims Leave Islam (2015), Simon Cottee challenged Leaving Islam's assertion that the fact that the death penalty for apostasy is supported by several passages in the hadith, this means this reflects the 21st-century mainstream Muslim opinion on the matter.[2]

Translations

- Dutch: Weg uit de islam: getuigenissen van afvalligen, 557 pages, Uitgeverij Meulenhoff, Amsterdam (2008), ISBN 978-90-290-8153-5[5]

See also

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.