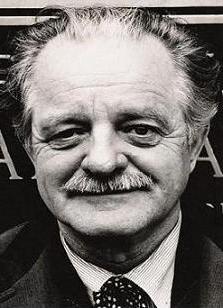

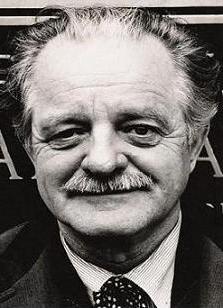

Kenneth Rexroth

American poet (1905–1982) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Kenneth Charles Marion Rexroth (December 22, 1905 – June 6, 1982)[1] was an American poet, translator, and critical essayist. He is regarded as a central figure in the San Francisco Renaissance, and paved the groundwork for the movement.[2][3] Although he did not consider himself to be a Beat poet, and disliked the association, he was dubbed the "Father of the Beats" by Time magazine.[4] Largely self-educated, Rexroth learned several languages and translated poems from Chinese, French, Spanish, and Japanese.[5]

Kenneth Rexroth | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 22, 1905 |

| Died | June 6, 1982 (aged 76) |

| Occupation | Poet, writer, translator, critic, musician |

| Spouse(s) | Andrée Rexroth |

| Awards |

|

Early life

Rexroth was born Kenneth Charles Marion Rexroth in South Bend, Indiana,[6] the son of Charles Rexroth, a pharmaceuticals salesman, and Delia Reed. His childhood was troubled by his father's alcoholism and his mother's chronic illness. His mother died in 1916 and his father in 1919, after which he went to live with his aunt in Chicago and enrolled in the Art Institute of Chicago.[7]

At age 19, he hitchhiked across the country, taking odd jobs and working a stint as a Forest Service trail crew hand, cook and packer at the Marblemount Ranger Station in the Pacific Northwest.[8]

Poetry career

Summarize

Perspective

In the 1930s, Rexroth was associated with the Objectivists, a largely New York group gathered around Louis Zukofsky and George Oppen.[9] He was included in the 1931 issue of Poetry magazine dedicated to Objectivist poetry, and in the 1932 An “Objectivists” Anthology.[10] Much of Rexroth's work can be classified as "erotic" or "love poetry", given his deep fascination with transcendent love. According to Hamill and Kleiner, "nowhere is Rexroth's verse more fully realized than in his erotic poetry".[4]

With The Love Poems of Marichiko, Rexroth claimed to have translated the poetry of a contemporary, "young Japanese woman poet", but it was later disclosed that he was the author, and he gained critical recognition for having conveyed so authentically the feelings of someone of another gender and culture.[11] Linda Hamalian, his biographer, suggests that, "translating the work of women poets from China and Japan reveals a transformation of both heart and mind".[4]

With Rexroth acting as master of ceremonies, Allen Ginsberg, Philip Lamantia, Michael McClure, Gary Snyder, and Philip Whalen performed at the famous Six Gallery reading on October 7, 1955.[12] Rexroth later testified as a defense witness at Ferlinghetti's obscenity trial for publishing "Howl". Rexroth had previously sent Ginsberg (new in the Bay Area) to meet Snyder, and was thus responsible for their friendship. Lawrence Ferlinghetti named Rexroth as one of his own mentors.[13] Rexroth was eventually critical of the Beat movement. Years after the Six Gallery reading, Time referred to him as "Father of the Beats.[4] Rexroth ostensibly appears in Jack Kerouac's novel The Dharma Bums as Reinhold Cacoethes.[14]

Politics

As a young man in Chicago, Rexroth was involved with the anarchist movement and was active in the IWW.[8] Fellow poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti recalled that Rexroth self-identified as a philosophical anarchist, regularly associated with other anarchists in North Beach, and sold Italian anarchist newspapers at the City Lights Bookstore.[15]

Rexroth, a pacifist, was a conscientious objector during World War II.[8]

Painter

Rexroth trained as an artist and was an avid painter into his 40s. His mediums were usually wax and silica on Masonite or board. In his introduction to an undated auction catalog of Rexroth's paintings, critic Bradford Morrow observes that his early works were mainly abstract, often geometric reminiscent of Mondrian, but that as time went on, Rexroth turned to more figurative treatment of his subjects.[16]

Last years

Rexroth died in Santa Barbara, California, on June 6, 1982.[6] He had spent his final years translating Japanese and Chinese women poets, as well as promoting the work of female poets in America and overseas. The year before his death, on Easter, Rexroth converted to Roman Catholicism.[17]

Works

Summarize

Perspective

As author

(all titles poetry except where indicated)

- In What Hour? (1940). New York: The Macmillan Company

- The Phoenix and the Tortoise (1944). New York: New Directions Press

- The Art of Worldly Wisdom (1949). Prairie City, Il: Decker Press (reissued in 1953 by Golden Goose and 1980 by Morrow & Covici)

- The Signature of All Things (1949). New York: New Directions

- Beyond the Mountains: Four Plays in Verse (1951). New York: New Directions Press

- The Dragon and the Unicorn (1952). New York: New Directions Press

- Thou Shalt Not Kill: A Memorial for Dylan Thomas (1955). Mill Valley: Goad Press

- In Defense of the Earth (1956). New York: New Directions Press

- Bird in the Bush: Obvious Essays (1959) New York: New Directions

- Assays (1961) New York: New Directions (essays)

- Natural Numbers: New and Selected Poems (1963). New York: New Directions

- Classics Revisited (1964; 1986). New York: New Directions (essays).

- Collected Shorter Poems (1966). New York: New Directions.

- An Autobiographical Novel (1966). New York: Doubleday (prose autobiography)(expanded edition 1991 by New Directions)

- Heart's Garden, The Garden's Heart (1967). Cambridge: Pym-Randall Press

- Collected Longer Poems (1968). New York: New Directions.

- The Alternative Society: Essays from the Other World (1970). New York: Herder & Herder.

- With Eye and Ear (1970). New York: Herder & Herder.

- American Poetry in the Twentieth Century (1971). New York: Herder & Herder (essay).

- Sky, Sea, Birds, Trees, Earth, House, Beasts, Flowers (1971). Santa Barbara: Unicorn Press

- The Elastic Retort: Essays in Literature and Ideas (1973). Seabury.

- Communalism: From Its Origins to the Twentieth Century (1974). Seabury (non-fiction).

- New Poems (1974). New York: New Directions

- The Silver Swan (1976). Port Townsend: Copper Canyon Press

- On Flower Wreath Hill (1976). Burnaby, British Columbia: Blackfish Press

- The Love Poems of Marichiko (1978). Santa Barbara: Christopher's Books

- The Morning Star (1979) New York: New Directions

- Saucy Limericks & Christmas Cheer (1980). Santa Barbara: Bradford Morrow

- Between Two Wars: Selected Poems Written Before World War II (1982). Labyrinth Editions & The Iris Press

- Selected Poems (1984). New York: New Directions

- World Outside the Window: Selected Essays (1987). New York: New Directions

- More Classics Revisited (1989). New York: New Directions (essays).

- An Autobiographical Novel (1964; expanded edition, 1991). New York: New Directions

- Kenneth Rexroth & James Laughlin: Selected Letters (1991). New York: Norton.

- Flower Wreath Hill: Later Poems (1991). New York: New Directions.

- Sacramental Acts: The Love Poems (1997). Copper Canyon Press.

- Swords That Shall Not Strike: Poems of Protest and Rebellion (1999). Glad Day.

- Complete Poems (2003). Port Townsend: Copper Canyon Press.

- In the Sierra: Mountain Writings (2012). New York: New Directions (poems and prose).

- K. Rexroth: World Poems #17 (2017). Tokyo: Shichōsha (poems and prose in Japanese translation).

As translator

(in chronological order)

- Fourteen Poems by O. V. de L.-Milosz. (1952), San Francisco: Peregrine Press. Translated by Kenneth Rexroth, with illustrations by Edward Hagedorn. Second edition. (Port Townsend, WA): Copper Canyon Press, (1983). Paperbound. Issued without the Hagedorn illustrations.

- 30 Spanish Poems of Love and Exile (1956), San Francisco: City Lights Books.

- One Hundred Poems from the Japanese (1955), New York: New Directions.

- One Hundred Poems From the Chinese (1956), New York: New Directions.

- Poems from the Greek Anthology. (1962), Ann Arbor: Ann Arbor Paperbacks: The University of Michigan Press.

- Pierre Reverdy: Selected Poems (1969), New York: New Directions

- Love and the Turning Year: One Hundred More Poems from the Chinese (1970), New York: New Directions.

- 100 Poems from the French (1972), Pym-Randall.

- Orchid Boat (1972), Seabury Press. with Ling Chung; reprinted as Women Poets of China, New York: New Directions

- 100 More Poems from the Japanese (1976), New York: New Directions.

- The Burning Heart (1977), Seabury Press. with Ikuko Atsumi; reprinted as Women Poets of Japan, New York: New Directions

- Seasons of Sacred Lust: Selected Poems of Kazuko Shiraishi. (1978), (New York): New Directions.

- Complete Poems of Li Ch'ing-Chao. (1979), (New York): New Directions.

Discography

- Poetry Readings in the Cellar (with the Cellar Jazz Quintet): Kenneth Rexroth & Lawrence Ferlinghetti (1957) Fantasy #7002 LP (Spoken Word)

- Rexroth: Poetry and Jazz at the Blackhawk (1958) Fantasy #7008 LP (Spoken Word)

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.