Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

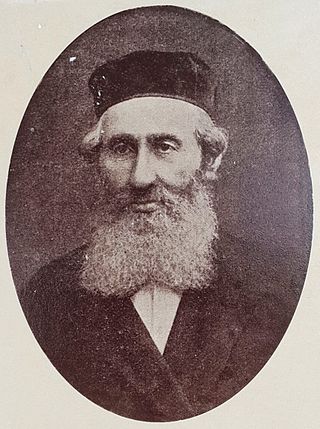

Kalman Schulman

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Kalman Schulman (1819 – 2 January 1899) was a Jewish writer who pioneered modern Hebrew literature.

Life

Summarize

Perspective

Schulman was born in 1819 in Bykhaw, Mogilev Governorate, Russia. He came from a Hassidic family.[1]

Schulman studied Hebrew and the Talmud in the heder, and two years after his marriage he began studying at the Volozhin Yeshiva. He was in the Yeshiva for six years, which caused an eye affection. To cure the affection, he moved to Vilnius and studied Talmud in the "klaus" of Elijah Gaon. He faced extreme poverty during that time, which led him to divorce his wife. He then left for Kalvarija and worked as a Hebrew instructor while commencing the grammatical study of Hebrew and German. In 1843, he returned to Vilnius and entered the yeshiva of Rabbi Israel Ginsberg (Zaryechev), receiving a rabbinical diploma from there. He first became known as a writer in 1846, when he wrote a petition to Moses Montefiore on behalf of Jews who resided within fifty versts of the German and Austrian borders and were driven from their homes by a special law from the Russian government.[2]

Schulman studied German while in the Volozhin Yeshiva and gained an interest in Haskalah. After he settled in Vilnius, he joined the city's circle of maskilic writers and became close friends with Micah Joseph Lebensohn. From 1849 to 1861, he taught Hebrew at the secondary school attached to the state rabbinical school. He then focused entirely on literary activity, receiving support from the Society for the Promotion of Culture among the Jews of Russia in Saint Petersburg.[1]

Schulman was under contract with Romm publishing house, who paid him so little he could barely support his families. His Hebrew books were mostly translations intended to spread Haskalah among the Hebrew-speaking public and youth, although they also proved popular in Orthodox circles. One of his widely read abridged translations was Eugène Sue's The Mysteries of Paris, which Schulman published from 1857 to 1860 and was republished with five more editions over the next half-century. The translation was considered by one source as an innovative experiment in translating contemporary novels into Hebrew, although it also caused controversy among those who considered it a sacrilege to use Hebrew to describe the Parisian underworld. The controversy deterred him from translating more novels and led him to focus more on translating and adapting scientific books.[3]

Schulman freely Weber's History of the World in nine volumes from 1867 to 1884. Using a secondary source, he also translated Josephus' Life in 1859, and from 1861 to 1863 he translated Jewish War and Antiquities. He wrote a ten-volume work on world geography called Mosede Eretz from 1871 to 1878, a four-volume biographical book of great Jewish personalities called Toledoth Hachme Yisrael that was adopted from Heinrich Graetz from 1872 to 1878, and two volumes on the geography of Palestine and the Near East called Halichoth Kedem in 1848 and 1854. He published several collected essays and sketches, both original and adapted, on historical and geographical subjects, especially Palestine. The published collected essays included Ariel in 1856, Harel in 1864, Habatzeleth Hasharon in 1881, Minhath Ereb in 1889, and Eretz Hakedem in 1890. A prolific writer, he produced over twenty volumes, mostly translations and adaptions.[4]

Schulman was a moderate maskil with a firmly religious outlook. His translations understated elements that contradicted Jewish tradition and included religious elements. While his Orthodox tendencies angered more radical maskilim like Moshe Leib Lilienblum, it also meant his work was popular with a large audience of traditional readers who saw them as safe to read. Some critics considered him a harbinger of Zionism, due to his books on Israel. However, his work on Israel was written more from a lens of religious romanticism, than from nationalist motives.[1]

Schulman died in Vilnius on 2 January 1899.[2]

Remove ads

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads