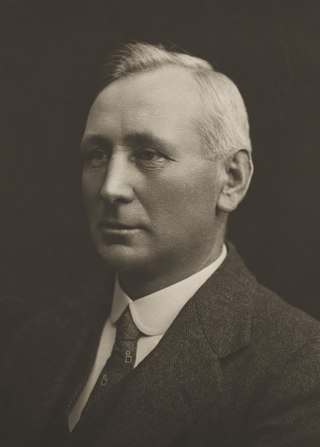

John Wren

Australian businessman From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

John Wren (3 April 1871 – 26 October 1953) was an Australian bookmaker, boxing and wrestling promoter, Irish nationalist, land speculator, newspaper owner, racecourse and racehorse owner, soldier, pro-conscriptionist and theatre owner.[1] He became a legendary figure thanks mainly to a fictionalised account of his life in Frank Hardy's novel Power Without Glory, which was also made into a television series. After his death in 1953, Wren was buried at Boroondara Cemetery in Kew, Victoria.

Early life

John Wren was born in Collingwood, Melbourne, on 3 April 1871. He was the third son of Irish immigrants John Wren Snr., a labourer, and Margaret, née Nester. He left school at the age of 12 and worked in a woodyard and as a boot clicker, while supplementing his wage through various gambling activities. Losing his job in the 1890s depression, he commenced a successful horse-racing gambling venture at his Johnston Street totalizator, which eventually earned him £20,000 per year (A$2,646,000 in 2021 terms).[1]

In 1916, he took over J. L. Garvan's Stadia Ltd, of which Snowy Baker was general manager, and parlayed it into a major business – Stadiums Pty Ltd.[2]

Power Without Glory

In 1950, the novelist Frank Hardy portrayed Wren negatively in his self-published 1950 novel Power Without Glory, in which Wren appears thinly disguised as a character called John West. The book also included characters based on other important Victorian and Australian political figures, including Victorian Premier Sir Thomas Bent and Prime Minister James Scullin, as well as Roman Catholic Archbishop Daniel Mannix. Due to the fact that Hardy was a member of the Communist Party of Australia, the book, and its criticisms of Wren, became politically embroiled in the anti-communist culture of the Cold War.[3] John Wren's wife, Ellen Wren, sued Hardy for libel after the book's publication.[clarification needed]

Other books about John Wren

Frank Brennan's son, the author Niall Brennan, gave a favourable portrayal of Wren in his 1971 biography, John Wren: Gambler. Hugh Buggy's The Real John Wren (1977), with a foreword by Arthur Calwell, Federal Parliamentary Labor Party Deputy Leader, was also very favourable. An alternative account was given by Chris McConville's article in Labor History, "John Wren: Machine Boss" (1981). John Wren: A Life Reconsidered by James Griffin (2004) presented an essentially positive view of Wren's life and career.

Family

Wren's granddaughter Gabrielle Pizzi also achieved renown as an art dealer credited with raising the profile of Aboriginal art. Others of his children had troubled lives. His son Anthony committed suicide after being disinherited following an argument with Wren, while his daughter-in-law Nora and grandchildren only received a meagre allowance. When another of Wren's grandchildren, Susan Wardlaw, died,[4] her two brothers had her buried without notifying her husband Greg, who was then given 24 hours to leave the family home, while another of Wren's daughters, Angela, purportedly died of malnutrition when she was 39, leaving an estate worth £97,000.[5]

Collingwood benefactor

Wren was well known for supporting exemplary Collingwood players in the VFL's pre-professionalised era. While players were paid a per-game salary, the amount was meagre until the late 20th century when the sport became professionalised. To compensate for this, Wren was known to send monetary gifts to players who performed well, often paying ten to twenty times the normal game salary to certain Collingwood players. Among the beneficiaries included Collingwood legend Gordon Coventry after he scored a then-record 16 goals in a game in 1929; however, in his case, League Laws prevented him from doing this, so he exploited a loophole by gifting A£50 to Coventry's wife (A$4,449 in 2022 terms) to buy a suite of furniture.

In 1952, Wren donated A£500 (A$20,784 in 2022 terms), which was to be distributed among Collingwood players.[6]

In another example of generosity, Lou Richards recalled on The Sunday Footy Show a time when Wren asked Richards how much he was paid the week prior. When Richards replied "a pound note, sir", Wren gifted Richards A£20 (potentially up to A$1,819 in 2022 terms, as the year this happened was not clarified).[7]

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.