Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

John Heysham Gibbon

American surgeon From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

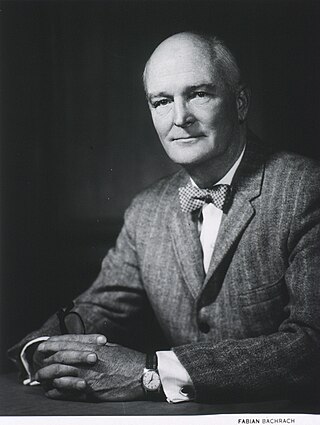

John Heysham Gibbon (September 29, 1903 – February 5, 1973) was an American surgeon best known for inventing the heart–lung machine and performing subsequent open-heart surgeries which revolutionized heart surgery in the twentieth century. He was the son of Dr. John Heysham Gibbon Sr., and Marjorie Young Gibbon (daughter of General Samuel Young), and came from a long line of medical doctors including his father, grandfather Robert, great-grandfather John and great-great grandfather.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2018) |

Remove ads

Early years and education

Gibbon was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on September 29, 1903. Descended from the Gibbon family, who first arrived in Philadelphia from Wiltshire, England in 1684, his father was a surgeon at Pennsylvania Hospital and the Hospital of Jefferson Medical College.

Gibbon was the second oldest of four children and grew up attending the Penn Charter School in Philadelphia. He entered Princeton University at 16 and received his AB in 1923. He went to medical school at Jefferson Medical College of Philadelphia and received his MD in 1927. He completed his internship at Pennsylvania Hospital from 1927 to 1929.

Remove ads

Research and the heart-lung machine

Summarize

Perspective

Gibbon completed a research fellowship in surgery at Harvard Medical School under Edward Delos Churchill from 1930–31 and 1933–34 and became an assistant surgeon from 1931-1942 at Pennsylvania Hospital and Bryn Mawr Hospital. It was during his research fellowship at Harvard in 1931 when he first developed the idea for a heart-lung machine. A patient had developed a massive pulmonary embolism following a cholecystectomy. The team, under Dr. Churchill, performed a pulmonary embolectomy on her but she did not survive. Gibbon believed that a machine that would have taken her venous blood, oxygenated it and returned it to her arterial system would have saved her. He began work on this machine experimenting on cats at Harvard and continued this research at the University of Pennsylvania. He was successful at maintaining cardiorespiratory function of cats for nearly four hours and published these results in 1937.

During World War II, Gibbon served as a surgeon in the Burma China India Theater, achieving the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and becoming chief of surgery at Mayo General Hospital.

Gibbon continued his research upon his return and on May 6, 1953, he was able to perform the first successful open heart procedure, an ASD closure, on an 18-year-old patient using total cardiopulmonary bypass.[2] The patient lived for over 30 more years. For this achievement, he was awarded the Lasker Award in 1968 and the Gairdner Foundation International Award in 1960, the second and third most prestigious awards in medicine, respectively.

Remove ads

Career

After the war, Gibbon was appointed assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania in 1945 before accepting the title of Professor of Surgery and Director of Surgical Research at Jefferson Medical College. In 1956, he was appointed the Samuel D Gross Professor of Surgery and Chief of Surgery of Jefferson Medical College and its hospital.

Gibbon retired in 1967 and died after a game of tennis in 1973 of a heart attack. His papers are held at the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland.[3]

Personal life

Gibbon married Mary Hopkinson, daughter of painter Charles Hopkinson. His wife Mary was an assistant to his development of the heart-lung machine. They had four children: Mary, John, Alice and Marjorie. After his surgical career he retired in Lynnfield Farm in Media, PA, where he devoted himself to his hobbies - painting and poetry.[4]

Titles and achievements

- President of the American Surgical Association - 1954

- President of the American Association of Thoracic Surgeons - 1960-61

- President of the Society for Vascular Surgery - 1964-65

- National Academy of Sciences - (elected, 1972)

- Chairman of Annals of Surgery - 1947-57

Awards

- Gairdner Foundation International Award - 1960

- Lasker Award in clinical research - 1968

- Dickson Prize - 1973

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads