Joe Moakley

American politician (1927–2001) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

John Joseph Moakley (April 27, 1927 – May 28, 2001) was an American politician who served as the United States representative for Massachusetts's 9th congressional district from 1973 until his death in 2001. Moakley won the seat from incumbent Louise Day Hicks in a 1972 rematch; the seat had been held two years earlier by the retiring Speaker of the House John William McCormack. Moakley was the last Democratic chairman of the U.S. House Committee on Rules before Republicans took control of the chamber in 1995. He is the namesake of both Joe Moakley Park and the John Joseph Moakley United States Courthouse in Boston.

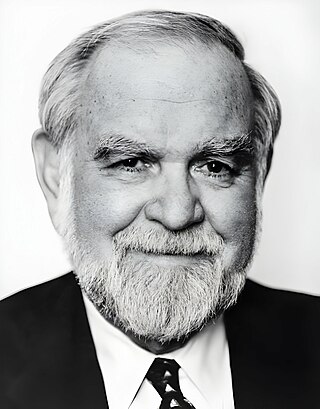

Joe Moakley | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 1999 | |

| Chair of the House Rules Committee | |

| In office May 30, 1989 – January 3, 1995 | |

| Preceded by | Claude Pepper |

| Succeeded by | Gerald Solomon |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 9th district | |

| In office January 3, 1973 – May 28, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Louise Day Hicks |

| Succeeded by | Stephen Lynch |

| Member of the Massachusetts Senate from the 4th Suffolk district | |

| In office 1965–1971 | |

| Preceded by | John E. Powers |

| Succeeded by | William M. Bulger |

| Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from the 7th Suffolk district | |

| In office 1953–1963 | |

| Preceded by | William F. Carr |

| Succeeded by | William M. Bulger |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Joseph Moakley April 27, 1927 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | May 28, 2001 (aged 74) Bethesda, Maryland, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Evelyn Duffy

(m. 1957; died 1996) |

| Education | South Boston High School[1] Suffolk University (LLB) |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Navy |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Early life and education

Moakley was born in South Boston, Massachusetts, April 27, 1927, and grew up in the Old Harbor public housing project. Lying about his age, he enlisted in the United States Navy during World War II and was involved in the Pacific War from 1943 to 1946.[2] After returning home, Moakley attended the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Florida from 1950 to 1951, and he received his LL.B. at Suffolk University Law School in Boston in 1956.

Career

Summarize

Perspective

In 1958, he partnered with his Suffolk classmate Daniel W. Healy, and together they opened a law practice at 149A Dorchester Street in South Boston. They remained legal partners into the late 1970s.

Moakley was a member of the Portuguese American Civic Club located in Taunton, Massachusetts. Moakley served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives from 1953 to 1963 and in the Massachusetts Senate from 1964 to 1970.[3] He was a delegate to the 1968 Democratic National Convention.[3] After the retirement of longtime Congressman John W. McCormack, Moakley ran for the Democratic nomination in the Ninth District but lost to Boston School Committee chair Louise Day Hicks, who gained support based on her opposition to school desegregation.[2] He was a member of the Boston City Council from 1971 to 1973.[3]

In 1972, Moakley ran as an independent against Hicks and defeated her by 3,448 votes.[2] Moakley was sworn in to Congress on January 3, 1973, one day after having switched his party affiliation back to the Democratic Party.[3] He was reelected 14 times, never facing substantive opposition. He faced Republican challengers only six times; the other times, he was either completely unopposed or faced only minor-party opposition. In 2002, he posthumously received the Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience Award for his unrelenting commitment to ending the war in El Salvador and throughout Central America, and for the compassionate care he gave his constituents in Massachusetts for nearly three decades.

He was succeeded in office by fellow Democrat Stephen Lynch.

Opposition to the legislative veto

Moakley was prominent in the opposition to the legislative veto, which became an increasingly popular device in the 1970s. He held up in committee a controversial bill proposed by Rep. Elliott Levitas that proposed to institute the legislative veto as a general feature of legislation. His position was vindicated when the Supreme Court held in INS v. Chadha (1983) that the legislative veto violated the bicameralism and presentment clauses of the U.S. Constitution.[4]

The Moakley Commission

Moakley led a special panel that investigated the 1989 deaths of six Jesuit priests and two women in El Salvador. The United States ended its military aid to El Salvador in part because of the Moakley Commission's report implicating several high-ranking Salvadoran military officials in the murders.[5] Moakley had a close relationship with Salvadoran activist Leonel Gómez Vides.[6][7]

Later career

Joe Moakley chaired the Committee on Rules from the 101st Congress through 103rd Congress.

In 1996, Moakley declined an offer to have a new bridge in Boston named in his honor, but accepted the suggestion to have the bridge named for his wife, following her death from cancer.[8] The Evelyn Moakley Bridge is next to a U.S. Courthouse, which was subsequently named the John Joseph Moakley United States Courthouse shortly before his death. Joe Moakley Park in South Boston is also named after him.[9]

Moakley's efforts led to the acquisition by Bridgewater State College (Bridgewater, MA) of a $10 million grant. The grant allowed the construction of the campus fiber network and a new regional telecommunications facility, which dramatically enhanced the teaching capabilities of the region's educational professionals. The John Joseph Moakley Center for Technological Applications in Bridgewater provides training in the use of technology for students, teachers, and members of the workforce. The three-story building houses a large computer lab, a television studio, an auditorium, and numerous classrooms.

Personal life

In 2001, Moakley announced that he would not be running for re-election for his 16th term in 2002, due to his ongoing battle with myelodysplastic syndrome. Moakley died on May 28, 2001, in Bethesda, Maryland.[2] His body was interred in Blue Hill Cemetery, Braintree, Massachusetts.

The Hematological Cancer Research Investment and Education Act, enacted in 2002, established the Joe Moakley Research Excellence Program for expanded and coordinated blood cancer research programs.[10]

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.