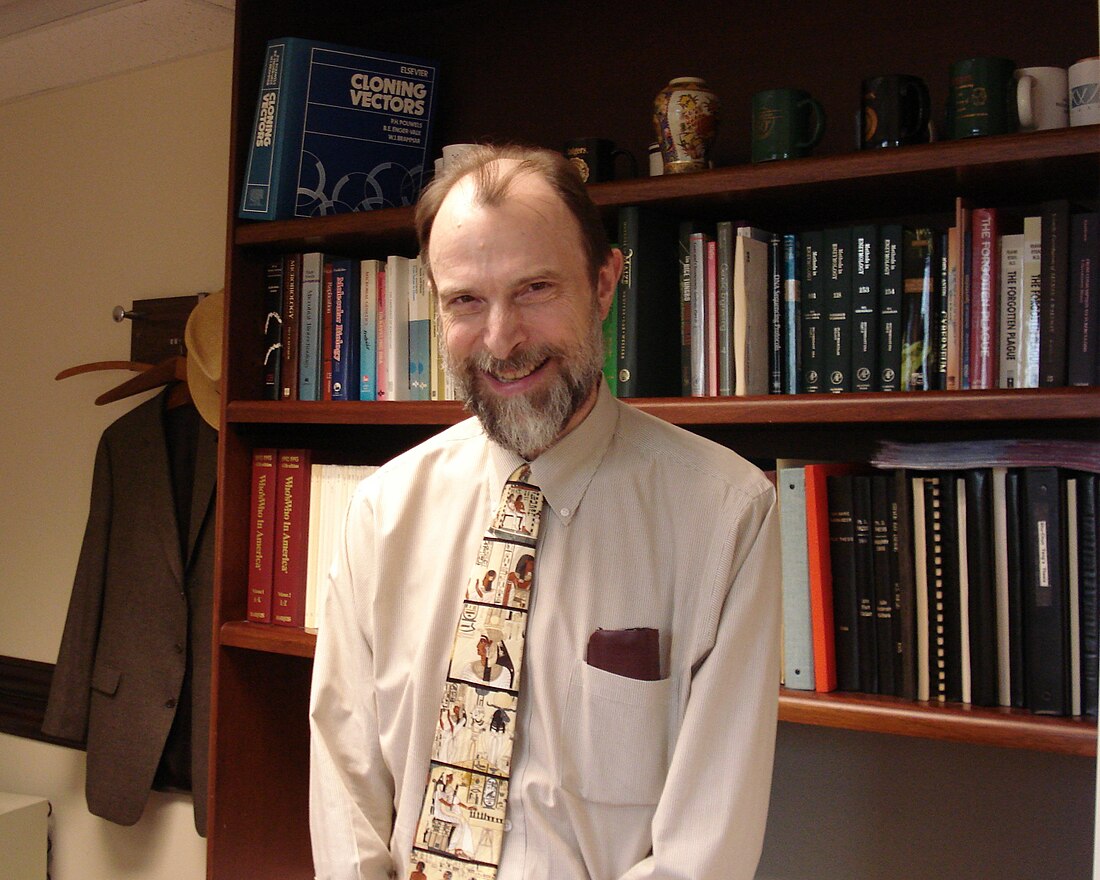

Joachim Messing

German-American biologist (1946–2019) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Joachim Wilhelm "Jo" Messing (September 10, 1946 – September 13, 2019) was a German-American biologist who was a professor of molecular biology and the fourth director of the Waksman Institute of Microbiology at Rutgers University.[1]

Joachim Messing | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Joachim Wilhelm Messing September 10, 1946 Duisburg, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany |

| Died | September 13, 2019 (aged 73) Somerset, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Free University of Berlin, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biology |

| Institutions | University of California, Davis, University of Minnesota, Rutgers University |

Upon his arrival at Rutgers in 1985, Jo Messing initiated research activity on computational and structural biology and further emphasis on molecular genetics of the regulation of gene expression and biomolecular interactions.[2] In the eighties, he provided incubator space for two Biotechnology centers at Rutgers, one in Medicine and one in Agriculture.[3] Subsequently, he also founded two new departments at Rutgers and served as the first chair, the Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry and the Department of Genetics.

Messing was also involved in the Plant Genome Initiative at Rutgers, which has contributed to the sequencing of the maize, sorghum, and the rice genome.[4][5] Besides maize, sorghum, and rice, they have also contributed to the sequencing of the Brachypodium[6] and Spirodela genomes.[7]

Messing died at his home in Somerset, New Jersey on September 13, 2019, three days after his 73rd birthday.[8]

Research

Summarize

Perspective

Jo Messing was a pharmacist by training, but specialized in molecular biology during his PhD-research at the LM University of Munich and the Max-Planck Institute of Biochemistry.

In the late seventies and early eighties, Jo Messing and his colleagues developed the shotgun DNA sequencing method with single and paired synthetic universal primers. The method is based on fragmenting DNA into small sizes, purifying them by cloning, and defining the start of sequencing with a short oligonucleotide.[9][10] Because fragmentation produces overlapping fragments, sequences can be concatenated by overlapping sequence information,[11] thereby reconstructing contiguous sequences (contigs), which was first exemplified by the complete structure of a plant DNA virus.[12] His cloning vectors were also used to develop the method for oligonucleotide site-directed mutagenesis.[13] DNA cloning, shotgun sequencing and site-directed mutagenesis became widely used to sequence large DNA molecules like human chromosomes and to engineer genes and proteins. These methods are freely available, have been the cornerstone of the biotechnology industry and are cited in many patents.

At Rutgers, his plant genetics initiatives were directed towards the evolution of plant chromosomes and gene duplication. He also did research in non-Mendelian inheritance. Applied research in these genomic sequences permitted his laboratory to study the organization and evolution of the genes that control the supply of proteins for nutrition and as sources of biofuel. Projects with maize focused on upgrading the nutritional value of corn by genetically modifying corn to make methionine and lysine in the seeds, two essential amino acids that people and livestock need in their diet. Investigating the genetic properties of sorghum led to a natural sorghum variant with increased sugar in the stem allows the plant to be used for both biofuel and feed. Most recent initiatives investigating the properties of spirodela (duckweed) led to its discovery as an alternative bio-energy source.[14]

Education

- 1968: B.S. in Pharmacy, Düsseldorf, Germany

- 1971: M.S. in Pharmacy, Free University of Berlin, Berlin

- 1975: Dr. rer. nat. in Biochemistry/Pharmacy Ludwig-Maximilians University, Munich, Germany[15]

Professional career

- 1975–1978: Research Fellow, Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Munich, Germany

- 1978–1980: Research Associate in Bacteriology, University of California, Davis, CA

- 1980–1982: Assistant Professor of Biochemistry, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN

- 1982–1984: Associate Professor of Biochemistry, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN

- 1984–1985: Professor of Biochemistry, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN

- 1985–2019: University Professor of Molecular Biology, Rutgers University

- 1988–2019: Director, Waksman Institute, Rutgers University

Awards and honors

- 1981-1990 World's most-cited scientist[16]

- 1985-1986 The most cited 1985 paper in the life sciences[17]

- 2002 Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science[18]

- 2004 United States Secretary of Agriculture Honor Award for (US Rice Genome)[19]

- 2007 Member of the National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina (Germany)[20]

- 2009 Inaugural Chair of the Selman Waksman Endowed Chair in Molecular Genetics at Rutgers University[21]

- 2013 Wolf Prize in Agriculture[22]

- 2014 Elected to the 100 Most Influential People in New Jersey in Food Category[23]

- 2014 Promega Biotechnology Research Award of American Society for Microbiology[24]

- 2015 Fellow of American Academy of Microbiology[25]

- 2015 Member of National Academy of Sciences[26]

- 2016 Rutgers University created Joachim Messing Endowed Chair in Molecular Genetics[27]

- 2016 Member of American Academy of Arts and Sciences[28]

- Recognized as a Pioneer Member of the American Society of Plant Biologists. [29]

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.