Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

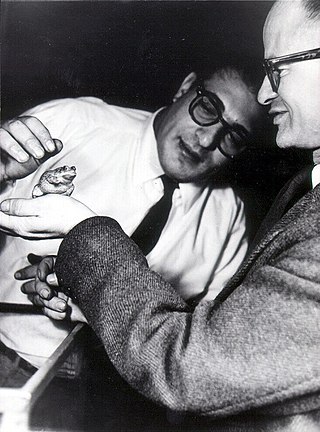

Jerome Lettvin

American cognitive scientist (1920–2011) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Jerome Ysroael Lettvin (February 23, 1920 – April 23, 2011), often known as Jerry Lettvin, was an American cognitive scientist, and Professor of Electrical and Bioengineering and Communications Physiology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He is best known as the lead author of the paper, "What the Frog's Eye Tells the Frog's Brain" (1959),[3] one of the most cited papers in the Science Citation Index. He wrote it along with Humberto Maturana, Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts, and in the paper they gave special thanks and mention to Oliver Selfridge at MIT.[4] Lettvin carried out neurophysiological studies in the spinal cord, made the first demonstration of "feature detectors" in the visual system, and studied information processing in the terminal branches of single axons. Around 1969, he originated the term "grandmother cell"[5] to illustrate the logical inconsistency of the concept.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2010) |

Lettvin was also the author of many published articles on subjects varying from neurology and physiology to philosophy and politics.[6] Among his many activities at MIT, he served as one of the first directors of the Concourse Program, and, along with his wife Maggie, was a houseparent of the Bexley dorm.[7]

Remove ads

Early life

Lettvin was born February 23, 1920, in Chicago, the eldest of four children (including the pianist Theodore Lettvin) of Solomon and Fanny Lettvin, Jewish immigrants from Ukraine. After training as a neurologist and psychiatrist at the University of Illinois (BS, MD 1943),[8] he practiced medicine during the Battle of the Bulge.[9] After the war, he continued practicing neurology and researching nervous systems, partly at Boston City Hospital, and then at MIT with Walter Pitts and Warren McCulloch under Norbert Wiener.

Remove ads

Scientific philosophy

Summarize

Perspective

Lettvin considered any experiment a failure from which the experimental animal does not recover to a comfortable happy life.[citation needed] He was one of the very few neurophysiologists who successfully recorded pulses from unmyelinated vertebrate axons. His main approach to scientific observation seems to have been reductio ad absurdum, finding the least observation that contradicts a key assumption in the proposed theory. This led to some unusual experiments. In the paper "What the Frog's Eye Tells the Frog's Brain", he took a major risk by proposing feature detectors in the retina. When he presented this paper at a conference, he was laughed off the stage by his peers,[10] yet for the next ten years it was the single most cited scientific paper. MIT Technology Review described this experiment:

"The assumption has always been that the eye mainly senses light, whose local distribution is transmitted to the brain in a kind of copy by a mosaic of impulses," he wrote. Instead of accepting that assumption, he attached electrodes to the frog's optic nerve so he could eavesdrop on the signals it sent. He then positioned an aluminum hemisphere around the frog's eye and moved objects attached to small magnets along the inner surface of the sphere by moving a large magnet on its outer side. By analyzing the signals the optic nerve produced when viewing the objects, Lettvin and his collaborators demonstrated the concept of "feature detectors"—neurons that respond to specific features of a visual stimulus, such as edges, movement, and changes in light levels. They even identified what they called "bug detectors", or cells in a frog's retina that are predisposed to respond when small, dark objects enter the visual field, stop, and then move intermittently. In short, Lettvin’s group discovered that a lot of what was thought to happen in the brain actually happened in the eye itself. "The eye speaks to the brain in a language already highly organized and interpreted, instead of transmitting some more or less accurate copy of the distribution of light on the receptors," he concluded.[10]

For Lettvin, a corollary to finding contradictions was taking risks: the bigger the risk, the likelier a new finding. Robert Provine quotes him as asking, "If it does not change everything, why waste your time doing the study?"[citation needed]

Lettvin was an outspoken critic of pseudo-scientific practices relied upon by many of the social sciences, as well as the potential threat posed by Artificial Intelligence. His presentation at the 1971 UNESCO symposium on Culture and Science[11] titled The Diversity of Cultures as against the Universality of Science and Technology[12] opens with the statement that “The comprehensive involvement of man in science is now fatal” and closes with the warning “For this is the new rationalism, the new messiah, the new church, and the new dark ages come upon us."

Lettvin made a careful study of the work of Leibniz, discovering that he had constructed a mechanical computer in the late 17th century.

Lettvin is also known for his friendship with, and encouragement of the cognitive scientist and logician Walter Pitts, a polymath who first showed the relationship between the philosophy of Leibniz and universal computing in "A Logical Calculus of Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity,"[13] a seminal paper Pitts co-authored with Warren McCulloch.

Lettvin continued to research the properties of nervous systems throughout his life, culminating in his study of ion dynamics in axon cytoskeleton.

Remove ads

Politics

Lettvin was a firm advocate of individual rights and heterogeneous society. His father nurtured these views with ideas from Kropotkin's book Mutual Aid. Lettvin became an expert witness in trials in both the United States and in Israel, always on behalf of individual rights.

During the anti-war demonstrations of the 1960s, Lettvin helped to negotiate agreements between police and protesters, and in 1968 he took part in the student takeover of the MIT Student Center in support of an AWOL soldier.[14] He deplored the making of laws based on false science and false statistics, and the distortion of observations for political or economic advantage.

When the American Academy of Arts and Sciences withdrew its award of the annual Emerson-Thoreau medal from Ezra Pound because of his vocal support for Italian Fascism, Lettvin resigned from the Academy and wrote in his resignation letter: "It is not art that concerns you but politics, not taste but special interest, not excellence but propriety."[15]

Debating

On May 3, 1967, in the Kresge Auditorium at MIT, Lettvin debated with Timothy Leary about the merits and dangers of LSD. Leary took the position that LSD is a beneficial tool in exploring consciousness. Lettvin took the position that LSD is a dangerous molecule that should not be used.[1][16][17]

Lettvin was a regular invitee at the Ig Nobel Prize ceremony as "the world's smartest man," and debated extemporaneously against groups of people on their own subjects of expertise.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Personal life

Lettvin married his wife, Maggie Lettvin in 1947. They had three children: David, Ruth, and Jonathan.

Death

Lettvin died on April 23, 2011, in Hingham, Massachusetts at the age of 91.

Published papers

Summarize

Perspective

Year Title, Publication, Issue; Contributing Authors[6]

- 1943 A Mathematical Theory of the Affective Psychoses, Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics, Vol. 5; (with Pitts)

- 1948 Somatic Functions of the Central Nervous System, Annual Review of Physiology Vol. 10; (with McCulloch)

- 1948 The Path of Suppression in the Spinal Grey Matter, Federation Proceedings, Vol. 7, No. 1, March; (with McCulloch)

- 1950 An Electrical Hypothesis of Central Inhibition and Facilitation, Proceedings of the Association for Research in Nervous and Mental Diseases, Vol. 30, December; (with McCulloch, Pitts, and Dell)

- 1950 Positivity in Ventral Horn During Bulbar Reticular Inhibition of Motoneurons Federation Proceedings, Vol. 9, No. 1, March; (with Dell and McCulloch)

- 1951 Changes Produced in the Central Nervous System by Ultrasound, Science, Vol. 114, No. 2974; (with Wall, Fry, Stephens, and Tucker)

- 1952 Sources and Sinks of Current in the Spinal Cord, Federation Proceedings, Vol. 11, No. 1, March; (with Pitts and Brazier)

- 1953 Comparaison entre les machines à calculer et le cerveau, Les machines à calculer et la pensée humaine, Vo.l. 37, pp. 425–443; (with McCulloch, Pitts, and Dell)

- 1953 On Microelectrodes for Plotting Currents in Nervous Tissue, Proceedings of the Physiological Society, Vol. 122; (with Howland, McCulloch, Pitts, and Wall)

- 1954 Maps Derived by Bipolar Microelectrode Stimulation Within the Spinal Cord, Federation Proceedings, Vol. 13, March; (with Pitts, McCulloch, Wall, and Howland)

- 1955 Physiology of a Primary Chemoreceptor Unit, Science, Vol. 122, No. 3166, September; (with Hodgson and Roeder)

- 1955 Reflex Inhibition by Dorsal Root Interaction, Journal of Neurophysiology, vol.18; (with Howland, McCulloch, Pitts, and Wall)

- 1955 Effects of Strychnine, with Special Reference to Spinal Afferent Fibers, Epilepsia, Series III, Vol. 4; (with Wall, McCulloch, and Pitts)

- 1955 The Terminal Arborisation of the Cat's Pyramidal Tract Determined by a New Technique, The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, Vol. 28, Nos. 3-4, Dec.-Feb.; (with Wall, McCulloch, and Pitts)

- 1956 Excitability Changes in Anatomical Components of the Monosynaptic Arc Following Tetanic Stimulation, Federation Proceedings, Vol. 15, No. 1, March; (with McCulloch and Pitts)

- 1956 Limits on Nerve Impulse Transmission, IRE Convention Record, National, Part 4, March 19–20; (with Wall, Pitts, and McCulloch)

- 1956 Central Effects of Strychnine on Spinal Afferent Fibers, A.M.A. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, Vol. 75: 323-324; (with McCulloch, Pitts, and Wall)

- 1957 Membrane Currents in Clamped Vertebrate Nerve, Nature, Vol. 180, pp. 1290–1291, Dec. 7; (with McCulloch, and Pitts)

- 1956/1957 Footnotes on a Headstage, IRE Transactions on Medical Electronics; (with Howland and Gesteland)

- 1956 Evidence that Cut Optic Nerve Fibers in a Frog Regenerate to their Proper Places in the Tectum, Science, Vol. 130, No. 3390, December; (with Maturana, McCulloch, and Pitts)

- 1959 How Seen Movement Appears in the Frog's Optic Nerve, Federation Proceedings Vol. 18, No. 1, March; (with Maturana, Pitts, and McCulloch)

- 1959 What the Frog's Eye Tells the Frog's Brain, Proceedings of the IRE, Vol. 47, No. 11, November; (with Maturana, McCulloch, and Pitts)

- 1959 Comments on Microelectrodes, Proceedings of the IRE, Vol. 47, No. 11, November; (with Gesteland, Howland, and Pitts)

- 1959 Number of Fibers in the Optic Nerve and the Number of Ganglion Cells in the Retina of Anurans, Nature, Vol. 183, pp. 1406–1407, May 16; (with Maturana)

- 1959 Bridge for Measuring the Impedance of Metal Microelectrodes, The Review of Scientific Instruments, Vol. 30, No. 4, April; (with Gesteland and Howland)

- 1960 Anatomy and Physiology of Vision in the Frog (Rana pipiens), The Journal of General Physiology, Vol. 43, No. 6, Supplement pp. 129–175; (with Maturana, McCulloch, and Pitts)

- 1961 Two Remarks on the Visual System of the Frog, Research Laboratory of Electronics, MIT, Vol. 38; (with Maturana, Pitts, and McCulloch)

- 1962 Translations of Poems by Morgenstern, The Fat Abbot, Fall/Winter 1962

- 1963 Odor Specificities of the Frog's Olfactory Receptors, Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Olfaction and Taste (Pergamon Press); (with Gesteland, Pitts, and Rojas)

- 1964 A Theory of Passive Ion Flux through Axon Membranes, Nature, Vol. 202, No. 4939, pp. 1338–1339, June; (with Pickard, McCulloch, and Pitts)

- 1964 Microelectrodes Research Laboratory of Electronics, MIT Encyclopedia of Electrochemistry, (Reinhold Publishing Corporation: New York), pp. 822–826; (with Gesteland, Howland, and Pitts)

- 1964 Receptor Model of the Frog's Nose, NEREM Record; (with Gesteland)

- 1964 Caesium Ions Do Not Pass the Membrane of the Giant Axon, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 52, No. 5, pp. 1177–1183; (with Pickard, Moore, Takata, Pooler, and Bernstein)

- 1964? Lanthanum Simulates High Calcium and Reduces Conductance Changes in Nerve Membranes, XXIII International Congress of Physiological Sciences; (with Moore, Takata, and Pickard)

- 1964 Passive Transport of Ions Across Nerve membranes, Minutes of the APS-NES 1964 Spring Meeting of the New England Section, 4 April; (with Pickard)

- 1964 Experiments in Perception, Tech Engineering News, November;

- 1965 Chemical Transmission in the Nose of the Frog, Journal of Physiology, Vol. 181, pp. 525–559; (with Gesteland, and Pitts)

- 1965 Octopus Optic Responses, Experimental Neurology, Vol. 12, No. 3, July; (with Boycott, Maturana, and Wall)

- 1965 Glass-Coated Tungsten Microelectrodes, Science, Vol. 148, No.3676, pp. 1462–1464; (with Baldwin, and Frenk)

- 1965 Speculations on Smell, Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology, Vol. 30; (with Gesteland)

- 1965 General Discussion: Early Receptor Potential, Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology, vol. 30; (with Platt, Wald, and Brown)

- 1966 Ionic Conductance Changes in Lobster Axon Membrane When Lanthanum is Substituted for Calcium, Journal of General Physiology, Vol. 50, Number 2, November; (with Takata, Pickard, and Moore)

- 1966 Alkali Cation Selectivity of a Squid Axon Membrane, N.Y. Academy of Sciences, vol. 137, pp. 818–829; (with Moore, Anderson, Blaustein, Takata, Pickard, Bernstein, and Pooler)

- 1966 A Demonstration of Ion-Exchange Phenomena in Phospholipid Mono-Molecular Films, Nature, Vol. 209, No. 5026, pp. 886–887, February; (with Rojas and Pickard)

- 1967 You Can't Even Step in the Same River Once, Journal of the American Museum of Natural History , Vol. 76, No. 8, October;

- 1967 The Colors of Colored Things, MIT Research Laboratory of Electronics Quarterly Progress Reports, No. 87, October 15, 1967

- 1968 A Code in the Nose, Cybernetic Problems in Bionics (Gordon and Breach Science Publishers); (with Gesteland, Pitts, and Chung)

- 1968 Pure Renaissance, Natural History, June–July, p. 62

- 1969 The Annotated Octopus, Natural History, Vol. 78, No. 9, p. 10; (Sokolski with notes by Lettvin)

- 1970 Multiple Meaning in Single Visual Units, Brain, Behavior and Evolution, vol.3, pp. 72–101; (with Chung and Raymond)

- 1970 The Rise and Fall of Progress, Natural History, Vol. 79, No. 3, pp. 80–82, March

- 1971 The Diversity of Cultures as against the Universality of Science and Technology, UNESCO Symposium on Culture and Science, Paris, France September 6–10, 1971;

- 1972 Scratched and Chiseled Marks of Man, Natural History

- 1974 The CLOOGE: A Simple Device for Interspike Interval Analysis, Proceedings of the Physiological Society, vol. 239, pp. 63–66, February; (with Chung and Raymond)

- 1976 A Physical Model for the Passage of Ions through an Ion-Specific Channel - I. The Sodium-Like Channel, Mathematical Biosciences, vol.32, pp. 37–50; (with Pickard)

- 1976 Probability of Conduction Deficit as Related to Fiber Length in Random-Distribution Models of Peripheral Neuropathies, Journal of the Neurological Sciences, Vol. 29, pp. 39–53; (with Waxman, Brill, Geschwind, and Sabin)

- 1976 The Use of Myth, Technology Review, Vol. 78(7), pp. 52–57

- 1976 On Seeing Sidelong, The Sciences, Vol. 16, No. 4, July/August

- 1977 The Gorgon's Eye, Technology Review, Vol. 80(2), pp. 74–83

- 1977 Freedoms and Constraints in Color Vision, Brain Theory Newsletter, Vol. 3, No. 2, December; (with Linden)

- 1978 Aftereffects of Activity in Peripheral Axons as a Clue to Nervous Coding, Physiology and Pathobiology of Axons, edited by Waxman (Raven Press: New York); (with Raymond)

- 1978 Relation of the E-Wave to Ganglion Cell Activity and Rod Responses in the Frog, Vision Research, Vol. 18, pp. 1181–1188; (with Newman)

- 1980 Anatomy and Physiology of a Binocular System in the Frog Rana pipiens, Brain Research Vol. 192, pp. 313–325; (with Gruberg)

- 1983 Processing of Polarized Light by Squid Photoreceptors, Nature, Vol. 304, pp. 534–536; (with Saidel and MacNichol)

- 1986 The Colors of Things, Scientific American, Vol.255.3, pp. 84–91; September (with Brou, Philippe, Sciascia, and Linden)

- 1995 Functional Properties of Regenerated Optic Axons Terminating in the Primary Olfactory Cortex

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads