Loading AI tools

American politician From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

James Noble Tyner (January 17, 1826 – December 5, 1904) was a lawyer, U.S. Representative from Indiana and U.S. Postmaster General. Tyner was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1869 and served three terms from 1869 to 1875.

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (August 2023) |

James Tyner | |

|---|---|

| |

| 26th United States Postmaster General | |

| In office July 12, 1876 – March 3, 1877 | |

| President | Ulysses S. Grant |

| Preceded by | Marshall Jewell |

| Succeeded by | David M. Key |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Indiana's 8th district | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 3, 1875 | |

| Preceded by | Godlove Orth |

| Succeeded by | Morton C. Hunter |

| Personal details | |

| Born | James Noble Tyner January 17, 1826 Brookville, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died | December 5, 1904 (aged 78) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

While in the House, Tyner opposed granting railroad subsidies, promoted gradual western industrial expansion, and spoke out against the Congressional franking privilege. In 1873, Tyner voted for the controversial Salary Grab Act that raised congressional pay, which resulted in his losing the Republican nomination for a fourth term. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Tyner Second Assistant Postmaster General in 1875 then U.S. Postmaster General in 1876, and he served until 1877.[1] Tyner served as First Assistant Postmaster General under President Rutherford B. Hayes from 1877 to 1881. In October 1881, President Chester A. Arthur requested his resignation because of his involvement in the Star Route postal frauds and for giving his son, whom he had appointed Superintendent of the Chicago Post Office, a $1,000 salary increase.

Tyner served as Assistant Attorney General in the U.S. Post Office Department from 1889 to 1893 and from 1897 to 1903. Tyner was a delegate to the International Postal Congresses in 1878 and 1897. Postmaster General Henry C. Payne requested his resignation in April 1903, after which Tyner was indicted for fraud and bribery. Tyner was acquitted after his family controversially removed pertinent papers from his office safe.

James Noble Tyner was born in Brookville, Indiana, on January 17, 1826, one of twelve children born to Richard Tyner and Martha Sedgwick Willis Swift Noble.[2][3] Tyner's grandfather, William E. Tyner, was a pioneer Baptist minister who preached in Eastern Indiana for many years.[3] His father was a prominent Indiana businessman, and his mother's brother was Indiana Governor Noah Noble. Another brother was U.S. Senator James Noble.[4] Tyner graduated from Brookville Academy in 1844 and joined his father's banking and business ventures.[2] Tyner then studied law, attained admission to the bar in 1857, and practiced in Peru, Indiana.[2]

From 1857 to 1861, Tyner was secretary of the Indiana Senate. In 1860, he served as a Republican presidential elector and cast his ballot for Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin. From 1861 to 1866, Tyner was a special agent for the United States Post Office Department.[2]

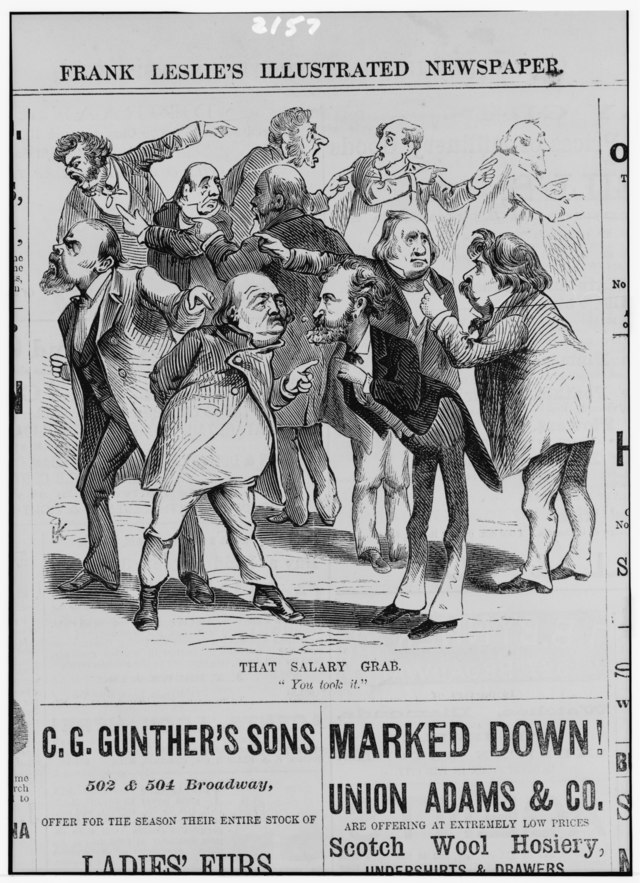

In 1869, Tyner was elected to the United States House of Representatives to fill the vacancy caused when Representative-elect Daniel D. Pratt resigned after winning a seat in the United States Senate.[2] Tyner represented Indiana's 8th District during the 41st, 42nd, and 43rd U.S. Congresses, March 4, 1869, to March 3, 1875.[2] Tyner, considered a reformer in his first two terms, gave few speeches in the House and was noted for his statistical accuracy and "sound reasoning".[5][6] After Congress passed the unpopular 1873 Salary Grab Act, many members lost their seats, and Tyner was among those who lost his party's nomination for reelection in 1874.[7]

On February 5, 1870, Tyner made his first House speech, in which he advocated for ending the Congressional Franking Privilege.[5] President Grant's Postmaster General John Creswell also advocated the end of franking, but efforts to eliminate it failed, and members of the U.S. House and U.S. Senate continued to send franked mail for free.

Tyner spoke against granting large land subsidies to the Northern Pacific Railroad.[6] In his view, the land between the Mississippi and the Pacific Ocean should be settled gradually over time, giving settlers free land to build houses.[6] Tyner considered America to be an empire and believed U.S. citizens had a right to settle the West.[6] On May 16, 1870, Tyner stated in a speech to the House, "Much as we desire to see the country lying between the Mississippi and the Pacific teaming with an industrious population, it would be far better to reach that end by slow marches than to rush into a policy that will eventually retard its prosperity and check its growth."[6]

On March 3, 1873, Grant signed a bill into law that increased the President's pay from $25,000 to $50,000, raised Congressional salaries from $5,000 to $7,500, and included a $5,000 bonus for House and Senate members. Tyner voted for the bill, which came to be known as the Salary Grab Act. Newspapers widely publicized the $5,000 bonus, and the bill was repealed in January 1874, though the president's salary raise remained in effect. The unpopularity of the Salary Grab led to many members of Congress losing their seats, and Tyner lost the Republican nomination when he ran for reelection in 1874.[7]

In February 1875, Grant appointed Tyner as Second Assistant U.S. Postmaster General, serving under Postmaster General Marshall Jewell and First Assistant Postmaster General James William Marshall. He served from February 26, 1875, to July 12, 1876, when he was appointed as Jewell's successor.

On July 12, 1876, President Grant appointed Tyner Postmaster General, serving until March 12, 1877. Tyner secured his old position of Second Assistant Postmaster General to his fellow Indianan and Civil War general Thomas J. Brady appointed by President Grant. Brady would later be involved and associated with the Star Route postal scandal that was revealed after President James A. Garfield took office in 1881.

After the end of the Grant administration, he was appointed to First Assistant Postmaster General by President Rutherford B. Hayes, serving from 1877 until his resignation in October 1881. When President James A. Garfield took office on March 4, 1881, there were rumors of fraud in the postal department where corrupt contractors made excessive profits on Star Routes. President Garfield had ordered an investigation on the matter by his appointed Postmaster General Thomas L. James.[9] Tyner was extremely familiar with the inner workings of the postal contract system and upon investigation by Postmaster General James was assumed to have known and allowed postal contract profiteering. James ordered Tyner to resign office by July, but after Garfield was assassinated and incapacitated, Tyner refused to leave. Also involved in the Star Route frauds was Tyner's Indiana friend and Second Assistant Postmaster Thomas J. Brady.[9] The investigation revealed that Tyner had given his son a lucrative job of $2,000 a year as Superintendent of the Chicago Post Office. When his son took the position Tyner had increased his salary from $1,000 to $2,000. When Garfield finally died on September 19, and his Vice President Chester A. Arthur took office, President Arthur finally forced Tyner to resign and vacate office on October 17, 1881.[9]

On the evening of June 12, 1882, Tyner was seriously injured, suffering a concussion and bruising on his face after being thrown from a buggy while riding near Brightwood.[10] Tyner recovered after being taken to the city and his wounds were dressed.[10]

Tyner was a delegate to the International Postal Congress in Paris in 1878 and in Washington, D.C., in 1897. Tyner served as Assistant Attorney General of the Post Office Department from 1889 to 1893 and again from 1897 to 1903.

On March 7, 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt launched an investigation into fraud in the Post Office.[11] Early in April, Postmaster General Henry C. Payne informed Tyner who was under suspicion of corruption to resign office by a mutual friend.[12] Tyner and Mrs. Tyner then pleaded with Payne to keep Tyner in office.[12] Payne then postponed Tyner's resignation to May 1 and told Tyner he was suspended from duties as Assistant Attorney barring Tyner from his office.[12] This left Tyner in a precarious position of technically being an Assistant Attorney without administrative powers.[12] Tyner instructed his wife to retrieve his official papers from the safe room in his Washington D.C. office on the fifth floor of the Postal Department.[12] On Tuesday, April 20 Mrs. Tyner arrived at Tyner's office at closing time 4 P.M., and was allowed to enter Tyner's office unsuspectedly alone.[12] Tyner's wife then secretly let in her sister-in-law and a company safe man by another door who unlocked the safe, after which, Mrs. Tyner retrieved all of Tyner's official papers.[12] Having bundled and packaged the papers Mrs. Tyner sent the papers by an African American messenger, who had also entered Tyner's office by another door, taking the papers to Tyner's residence. After her party had left by the other door, Mrs. Tyner walked out of Tyner's office alone and returned to Tyner's house.[12] The head of the Post Office Bureau George Christiancy, immediately discovered and informed Postmaster General Payne of Mrs. Tyner taking Tyner's papers from the safe.[12] Payne sent two investigators to Tyner's house, but Tyner and his wife refused to give the investigators Tyner's papers nor allow the investigators into Tyner's residence.[12]

On April 22, 1903, Assistant Attorney General Tyner was removed from office by Postmaster General Payne.[12] Four days later on April 26 Tyner and his wife denied any wrongdoing.[13] Tyner stated that he had served his country faithfully and the officials at the Post Office had "lost their heads".[13] Tyner stated he remained on as Assistant Attorney after March 9 to vindicate his honor.[13] Mrs. Tyner stated that she and her husband had been labeled robbers by the Postal Department.[13] Mrs. Tyner said that she had freely been allowed to go into Tyner's office room where the safe was located and nothing was done in secret.[13] Mrs. Tyner said she returned papers in a box to the Postal Department that did not have any criminal evidence.[13]

In mid-1903 Tyner was investigated for corruption in the Post Office by special prosecutor Charles J. Bonaparte and Fourth Assistant Postmaster General Joseph L. Bristow.[11] Tyner was indicted three times for fraud and one count bribery.[11] Also indicted was First Assistant Postmaster Perry S. Heath.[14] President Roosevelt stated the postal investigation revealed a condition of "gross corruption" in their offices.[14] Allegations against Tyner and Heath ranged from gross negligence of office, and criminal collusion, to actual participation in frauds, bribery, and financial profiteering.[14] Tyner was acquitted for lack of evidence since Tyner's wife had removed his papers from his office in April.[11] Bristow's investigation resulted in 41 indictments against 31 persons connected to the postal fraud.[14] Four postal officers and employees resigned, while thirteen workers were removed from office.[14]

Since July, 1902, Tyner had been suffering from paralysis, and the postal investigation trial in 1904 had strained his feeble health.[15] He died in Washington, D.C., on December 5, 1904, and was interred there in Oak Hill Cemetery.[15]

Tyner was the only member of the Grant Administration cabinet to hold a federal office appointment in the 20th Century serving under President William McKinley and President Theodore Roosevelt. [16] Elected three times to the House starting in 1869 Tyner was a successful mid-western politician, however, he was not reelected in 1874 due to his vote for the controversial Salary Grab Act. His long career in the Post Office Department was suspended in 1881 and finally ended in 1903 under suspicion of corruption. In 1903, Tyner and his wife's reputation was damaged after the controversy of taking official government documents from his office in Washington D.C.

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.