Loading AI tools

American judge (1825–1872) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

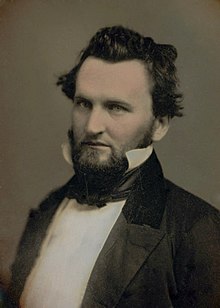

John Neely Johnson (August 2, 1825 – August 31, 1872) was an American lawyer and politician. He was elected as the fourth governor of California from 1856 to 1858, and later appointed justice to the Nevada Supreme Court from 1867 to 1871.[1] As a member of the American Party, Johnson remains one of only two members of a third party to be elected to the California governorship (the other was Hiram Johnson of the Progressive Party).

J. Neely Johnson | |

|---|---|

| |

| 4th Governor of California | |

| In office January 9, 1856 – January 8, 1858 | |

| Lieutenant | Robert M. Anderson |

| Preceded by | John Bigler |

| Succeeded by | John B. Weller |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 2, 1825 Gibson County, Indiana |

| Died | August 31, 1872 (aged 47) Salt Lake City, Utah Territory |

| Political party | Whig Party, American Party |

| Spouse | Mary Zabriskie |

| Children |

|

| Profession | Jurist, lawyer, politician |

| Signature |  |

Born in rural Gibson County, Indiana, Johnson never attended college; while born to a prominent family, his plans for his studies were foiled by economic effects of the Panic of 1837. He apprenticed a printer before moving to Iowa to work with a lawyer, and was admitted to practice law in Iowa.[2]

In July 1849, Johnson left Iowa for the Gold Rush in California, where he briefly employed himself as a gold prospector, and later as a mule train driver. Johnson restarted his law career in Sacramento, California by founding a law practice with Ferris Forman, and was elected as Sacramento City Attorney in 1850.[3] After two years in the City Attorney's office, Johnson began his political career by running as a Whig in the 1852 election, in which Johnson was elected to the California State Assembly as one of four members representing Sacramento.[4]

During his time in the Assembly, Johnson nearly broke a local editor's nose after accusing the editor of writing an insulting article about him. The editor aimed a pistol at Johnson, but was tackled by onlookers before he could fire.[5]

In 1854, both the state and federal wings of the Whig Party were on the verge on collapse due to party splits over the Kansas–Nebraska Act. In the wake of this split, Johnson joined the nativist American Party, known popularly as the Know Nothings.[citation needed]

In the 1855 general election, the American Party hoped to capitalize on the disintegration of the Whig party, internal Democratic divisions, and growing anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiment. The party nominated Assemblyman Johnson as its candidate for governor. Johnson ran against incumbent John Bigler, with Johnson securing the governorship by a comfortable margin. Johnson was described as "the most startled man in the state" upon hearing of his election.[5]

Along with the governorship, Know Nothings also received considerable gains in the California State Legislature, as well as elections to every other major executive post in the state, including the offices of Lieutenant Governor (Robert M. Anderson), Attorney General (William T. Wallace), Treasurer (Henry Bates), and Controller (George W. Whitman).[6]

Johnson was sworn in as the fourth governor of California on January 9, 1856. At 30, Johnson is the youngest governor in California history. Johnson inherited a growing state debt from the Bigler administration, and planned to reduce government expenditures to cut the debt. Early in his administration, Johnson agreed with legislation authored by San Francisco Assemblyman Horace Hawes to unite the city and county of San Francisco as a single entity to combat widespread corruption and lawlessness. The result of the legislation passed by Johnson was the Consolidation Act of 1856,[7][8] which unified the municipal and county governments, as well as separated the southern portion of San Francisco to later become San Mateo County.

Since the early 1850s, tensions within San Francisco political circles had sometimes erupted in open violence. In 1851, armed citizens formed the San Francisco Vigilance Movement to correct wrongs they saw being committed or protected by the municipal government. The vigilantes lynched two criminals being held in city jails. Governor John McDougall, condemned the actions of the vigilantes, but was not able to stop them because state law enforcement was too weak.

Distrust of city authorities again reached the surface on May 14, 1856, when James King of William, editor of the San Francisco Bulletin and a vocal critic of corrupt officials, was mortally wounded by James P. Casey, a purported ballot-box stuffer and city politician.[9] When Casey was in the custody of San Francisco law enforcement, William Tell Coleman, a ringleader in the 1851 Vigilance Committee and another vocal critic of municipal authorities, called for the formation of another Vigilante Committee. Vigilantes erected a barricade along Sacramento Street to repel city officers from removing them. After a week, the Vigilantes marched on the city jail and overpowered its guards to arrest Casey, along with another criminal: Charles Cora, who had fatally shot a U.S. Marshal the previous year.

Johnson traveled to San Francisco from Sacramento along with his brother William and the newly commissioned chief of the California Militia, Captain William Tecumseh Sherman to meet the Vigilante Committee ringleaders. Sherman recalled in his 1875 Memoirs Johnson angrily confronting Coleman and other Vigilante ringleaders in their makeshift headquarters and exclaiming, "Coleman, what the devil is the matter here?" Coleman replied that the San Franciscans "were tired of it, and had no faith in the officers of the law."[10] After personal negotiations between Governor Johnson and the Vigilantes over transferring the criminals to state law enforcement failed, Johnson watched helplessly as both Casey and Cora were hanged by the Vigilantes on May 20.

Johnson returned to Sacramento with the Vigilantes refusing to disperse, claiming they were San Francisco's rightful law enforcement. With the city's police and sheriff's departments outnumbered and trying to establish an armed presence in the streets, Mayor James Van Ness pleaded to Johnson for military assistance. Johnson responded by instructing Sherman to call the California Militia to San Francisco on June 2, and issued a gubernatorial proclamation declaring San Francisco in a state of insurrection the following day.[11] Johnson's proclamation, like McDougall's, was difficult to enforce. Johnson had instructed the California Militia to impose martial law, but without proper arms, the Militia needed more equipment to be provided by federal forces. Johnson ordered John E. Wool of the U.S. Army's Department of the Pacific based in Benicia to dispatch weapons to the state militia. General Wool declined, claiming that the Governor did not have the authority to use arms from federal soldiers because that right laid exclusively with the President.[12] Both Johnson and Sherman were furious about General Wool's refusal to lend arms for state militia forces: Sherman resigned from his military commission, vowing never to return to California politics. Meanwhile, the California Militia, under the command of Major General Volney E. Howard continued to gather arms, but suffered a major setback on June 21, 1856, when Vigilantes seized the arms schooner Julia.[13]

The Vigilantes remained San Francisco's de facto law enforcement until August 1856. Vigilantes arrested Chief Justice David S. Terry of the Supreme Court of California for stabbing a Vigilante member, and hanged two more individuals. Governor Johnson revoked his proclamation on San Francisco's insurrection on November 3.[14]

The Vigilante Crisis in the summer of 1856 overshadowed the rest of Johnson's term. Despite the fact that a large portion of the State Legislature were Know Nothing party members, Johnson vetoed a bill due to its "bad spelling, improper punctuation and erasures."[5] Johnson also approved funds to build the future California State Capitol. By 1857, Know Nothings were frustrated with Johnson's inability to deal with the San Francisco Vigilantes. During that year's American Party convention, Johnson lost the party's nomination for the governorship to George W. Bowie. Bowie would be defeated by Lecompton Democrat John Weller. Shortly after, the American Party ceased to be a major political force in California and elsewhere throughout the United States, and were absorbed by the Republican Party and sections of the Democratic Party.

Frustrated by his tenure in the California governorship and anxious for a new political start, Johnson relocated to western Utah Territory, which became Nevada Territory in March 1861. In 1863, Johnson was elected as a delegate to Nevada's first Constitutional Convention. Following its failed ratification vote, a second Constitutional Convention was called and he again became a delegate to, and this time was elected President of the Convention.[15] Nevada's electorate ratified this second attempt, and Nevada was admitted as a U.S. state on October 31, 1864.

In 1867, Nevada governor Henry G. Blasdel appointed Johnson to the Nevada Supreme Court. He served until 1871. After leaving the high court, Johnson contracted a severe case of sunstroke and died in Salt Lake City on August 31, 1872.[16]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.