J. C. Leyendecker

German-American illustrator (1874–1951) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Joseph Christian Leyendecker (March 23, 1874 – July 25, 1951) was one of the most prominent and financially successful freelance commercial artists in the U.S. He was active between 1895 and 1951 producing drawings and paintings for hundreds of posters, books, advertisements, and magazine covers and stories. He is best known for his 80 covers for Collier's Weekly, 322 covers for The Saturday Evening Post, and advertising illustrations for B. Kuppenheimer men's clothing and Arrow brand shirts and detachable collars. He was one of the few known reportedly gay artists working in the early-twentieth century U.S.[1][2][3]

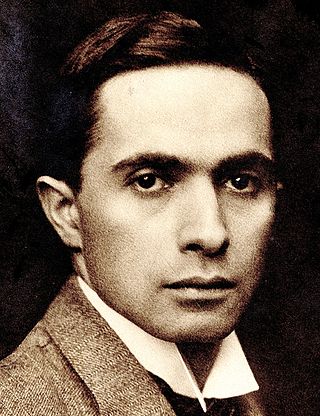

J. C. Leyendecker | |

|---|---|

Leyendecker in 1895 | |

| Born | Joseph Christian Leyendecker March 23, 1874 |

| Died | July 25, 1951 (aged 77) New Rochelle, New York, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | School of the Art Institute of Chicago Académie Julian |

| Known for | Illustration, painting |

| Partner | Charles A. Beach (1903–1951) |

Early life

Leyendecker (also known as 'J. C.' or 'Joe') was born on March 23, 1874, in Montabaur, Germany, to Peter Leyendecker (1838–1916) and Elizabeth Ortseifen Leyendecker (1845–1905). His brother and fellow illustrator Francis Xavier (aka "Frank") was born two years later. In 1882, the entire Leyendecker family immigrated to Chicago, Illinois, where Elizabeth's brother Adam Ortseifen was vice-president of the McAvoy Brewing Company. A sister, Augusta Mary, arrived after the family immigrated to America.[2][3]

As a teenager, around 1890, J. C. Leyendecker apprenticed at the Chicago printing and engraving company J. Manz & Company, eventually working his way up to the position of staff artist. At the same time he took night classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.[3]

After studying drawing and anatomy under John Vanderpoel at the Art Institute, J. C. and Frank enrolled in the Académie Julian[4] in Paris from October 1895 through June 1897. Upon their return to Chicago, the Leyendecker brothers took an apartment in Hyde Park. They also shared a studio in Chicago's Fine Arts Building at 410 South Michigan Ave.

Career

Summarize

Perspective

J. C. Leyendecker had a long career that extended from the mid-1890s until his death in 1951. During that time he worked for a wide range of commercial, editorial and government clients.

Before 1902: Chicago and Paris

As a staff artist at J. Manz & Company J. C. Leyendecker produced 60 Bible illustrations for the Powers Brothers Company, cover and interior illustrations for The Interior magazine, and frontispiece art for The Inland Printer. He also produced artwork for posters and book covers for the Chicago publisher E. A. Weeks.[5][6] He also provided artwork for a range of marketing materials for the Chicago men's clothier Hart, Schaffner & Marx.[7]

While in Paris, J. C. Leyendecker continued providing art to Hart, Schaffner & Marx, produced artwork for 12 covers of The Inland Printer, and won a contest (out of 700 entries) for the poster and cover of the midsummer 1896 issue of The Century Magazine, which garnered national newspaper and magazine coverage.[1][2][3]

Upon his return from Paris in June 1897, Leyendecker illustrated for a range of mostly local clients including Hart, Schaffner & Marx, the Chicago department store Carson, Pirie & Scott, the Eastern Illinois Railroad, the Northern Pacific Railroad, Woman's Home Companion magazine, the stone cutter's trade journal Stone, Carter's monthly, the bird hobbyist magazine The Osprey, and books including Conan Doyle's Micah Clarke and Octave Thanet's A Book of True Lovers.[1][2] He also painted 132 scenes of America for L. W. Yaggy's laptop panorama of Biblical scenes titled Royal Scroll published by Powers, Fowler & Lewis (Chicago).[8]

On May 20, 1899, Leyendecker received his first commission for a cover for The Saturday Evening Post launching a forty-four-year association with the magazine. Eventually, his work would appear on 322 covers of the magazine, introducing many iconic visual images and traditions including the New Year's Baby, the pudgy red-garbed rendition of Santa Claus, flowers for Mother's Day, and firecrackers on the 4th of July.[1]

During the 1890s, Leyendecker was active in Chicago's arts community. He exhibited with and attended social events by the Palette and Chisel Club, the Art Students League, and the Chicago Society of Artists. In December 1895, some of his posters were exhibited at the Siegel, Cooper & Company department store in Chicago. In January 1898 his posters for covers of The Inland Printer were exhibited at the Kimball Cafetier (Chicago).[2][9]

During his 1895–97 time studying in Paris, J. C. Leyendecker's work won four awards at the Académie Julian and one of his paintings titled "Portrait of My Brother" was exhibited in the Paris salon in 1897. One of his posters for Hart, Schaffner & Marx titled "The Horse Show" was exhibited as part of the award winning display of American manufacturers' posters at the Exposition Universelle (1900) in Paris.[7]

After 1902: New York City and New Rochelle

After relocating to New York City in 1902, Leyendecker continued illustrating books, magazine covers and interiors, posters, and advertisements for a wide range increasingly prominent clients.

His illustrations for men's product advertising, pulp magazines, and college posters earned him a reputation as specialist in illustrations of men.[10] Major clients included the Philadelphia suitmaker A. B. Kirschbaum,[7] Wick Fancy Hat Bands,[11] Gillette Safety Razors,[12] E. Howard & Co. watches, Ivory Soap, Williams Shaving Cream, Karo Corn Syrup, Kingsford's Corn Starch, Interwoven socks, B. Kuppenheimer & Co., Cooper Underwear, and Cluett Peabody & Company, maker of Arrow brand shirts and detachable shirt collars and cuffs.

The male models who appeared in Leyendecker's 1907–30 illustrations for Arrow shirt and collar ads were often referred to as "the" Arrow Collar Man. But a number of different men served as models, and some developed successful careers in theater, film, and television. Among the models were Brian Donlevy, Fredric March, Jack Mulhall, Neil Hamilton, Ralph Forbes, and Reed Howes.[13]

Among the men who modeled most frequently for Leyendecker was the Canadian-born Charles A. Beach (1881–1954). In 1903 Beach went to the artist's New York studio looking for modeling work.[14] Beach subsequently appeared in many of Leyendecker's illustrations. The two enjoyed a nearly 50-year professional and personal relationship. Many Leyendecker biographers have described that relationship as having a romantic and sexual dimension.[4][15][16][17]

Another important Leyendecker client was Kellogg's cereals. As part of a major advertising campaign, he painted a series of twenty different images of children eating Kellogg's Corn Flakes.[18]

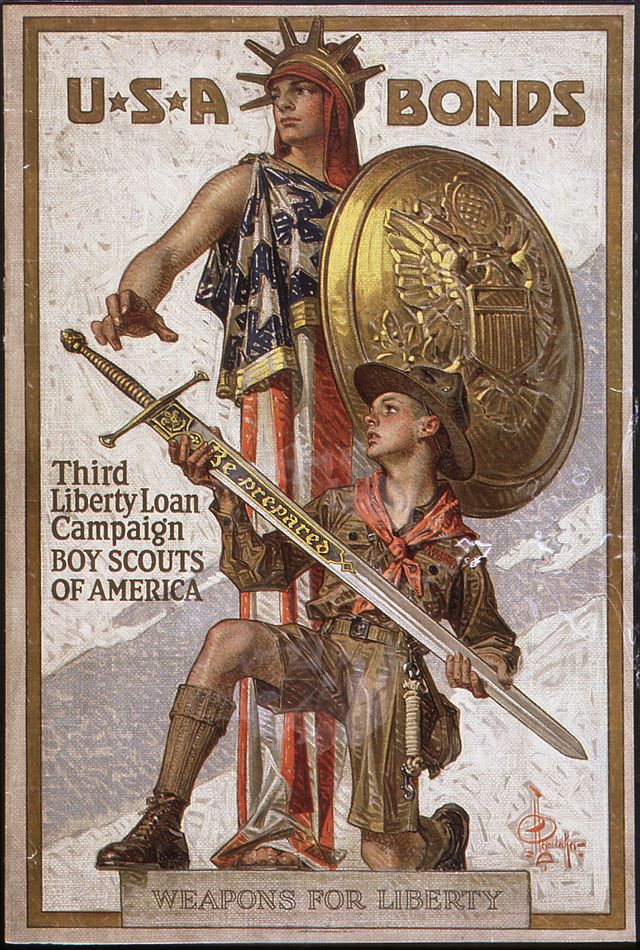

During the First and Second World Wars, Leyendecker painted military recruitment posters and war bonds posters for the U.S. government.

Decline of career

After 1930, Leyendecker's career began to slow, perhaps in reaction to the popularity of his work in the previous decade or as a result of the economic downturn following the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

Around 1930–31, Cluett Peabody & Company ceased using Leyendecker's illustrations in its advertisements for Arrow collars and shirts. In 1936, George Horace Lorimer, the famous editor at the Saturday Evening Post, retired and was replaced by Wesley Winans Stout (1937–1942) and then Ben Hibbs (1942–1962), both of whom rarely commissioned Leyendecker to illustrate covers.[19] Leyendecker's last cover for the Saturday Evening Post was of a New Year Baby for the January 2, 1943, issue.[20]

New commissions were fewer in the 1930s and 1940s. These included posters for the United States Department of War, in which Leyendecker depicted commanding officers of the armed forces encouraging the purchases of bonds to support the nation's efforts in World War II.[19]

Personal life

Summarize

Perspective

Sexuality

No statements (in Leyendecker's own words) survive concerning his sexual desires, behavior, or identity. But historians assess elements of his personal life as fitting the pattern they have identified for many gay men who lived during his time.[4][16][17][21][22]

Leyendecker never married, and he lived with another man, model Charles A. Beach, for most of his adult life (1903–1951).[14] Beach was Leyendecker's studio manager and frequent model, and many biographers describe Beach as Leyendecker's romantic, sexual, or life partner, for reasons stated before. They also describe Leyendecker as "gay" or "homosexual."[1][3][4][16][23]

Some historians have attributed the homoeroticism in some of Leyendecker's work to his sexuality, while others have pointed to the collaborative nature of commercial art making, which suggests the content of Leyendecker's work was more expressive of the times in which it was created than the artist's sexuality.[12][16][22][24][25]

Residences

In 1915, J. C., his brother Frank and sister Augusta Mary relocated from New York City to a newly built home and art studio in New Rochelle, New York, an art colony and suburb of New York City.[26] Sometime after 1918, Charles Beach also moved into the New Rochelle home.

Leyendecker and Beach reportedly hosted large galas attended by people of consequence from all sectors. The parties they hosted at their New Rochelle home/studio were important social and celebrity making events.[1]

While Beach often organized the famous gala-like social gatherings that Leyendecker was known for in the 1920s, he reportedly (by Norman Rockwell) also contributed largely to Leyendecker's social isolation in his later years. Beach reportedly forbade outside contact with the artist in the last months of his life.[27]

Due to his professional success, Leyendecker enjoyed a luxurious lifestyle with large home, domestic servants, and chauffeured car. However, when commissions began to wane during the Great Depression, he was forced to curtail spending considerably. By the time of his death, Leyendecker had let all of the household staff at his New Rochelle estate go. He and Beach tried to maintain their home themselves.[1][2][3]

Death, burial, disposition of estate

Leyendecker died on July 25, 1951, of an acute coronary occlusion at his home in New Rochelle. He was buried alongside his parents and brother Frank at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.[28]

Leyendecker's will directed his estate—house, furnishings, paintings, etc.—be divided equally between his sister Augusta Mary and Charles Beach. Though Leyendecker directed Beach to burn his drawings upon his death, Beach instead sold many of his drawings and paintings at a lawn sale.[3][14]

Other Leyendecker works were sold through New York's Society of Illustrators or given to the New York Public Library and Metropolitan Museum of Art. Sister Augusta Mary Leyendecker retained many of J. C. Leyendecker's paintings for Kellogg's cereals, and donated them along with other family ephemera upon her death to the Haggin Museum.[1][2]

Body of work

Summarize

Perspective

Notable clients

- Amoco

- Boy Scouts of America

- The Century Company

- Chesterfield Cigarettes

- Cluett, Peabody & Company

- Collier's Weekly

- Cooper Underwear

- Cream of Wheat

- Curtis Publishing Company

- Franklin Automobile

- Hart Schaffner & Marx

- Howard Watch

- Ivory Soap

- Karo Corn Syrup

- Kellogg Company

- Kuppenheimer

- Overland Automobile

- Palmolive Soap

- Pierce Arrow Automobile

- Procter & Gamble

- The Timken Company

- Saturday Evening Post

- U.S. Army

- U.S. Marines

- U.S. Navy

- Willys-Overland Company

Museum holdings

Examples of Leyendecker's original artwork can be found in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City), Norman Rockwell Museum (Stockbridge, MA), Haggin Museum (Stockton, CA), National Museum of American Illustration (Newport, RI), Lucas Museum of Narrative Art (Los Angeles, CA), and Pritzker Military Museum & Library in Chicago, IL. Significant collections of his work as reproduced can be found in many major archives and library collections including the Hagley Museum and Library (Wilmington, DE), Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library (Wilmington, DE), New York Public Library (New York, NY), and the D. B. Dowd Modern Graphic History Library Archives at Washington University in St. Louis (St. Louis, MO).

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

As the premier cover illustrator for the enormously popular Saturday Evening Post for much of the first half of the 20th century, Leyendecker's work both reflected and helped mold many of the visual aspects of the era's culture in America. The mainstream image of Santa Claus as a jolly fat man in a red fur-trimmed coat was popularized by Leyendecker, as was the image of the New Year Baby.[29] The tradition of giving flowers as a gift on Mother's Day was started by Leyendecker's May 30, 1914 Saturday Evening Post cover[30] depicting a young bellhop carrying hyacinths. It was created as a commemoration of President Woodrow Wilson's declaration of Mother's Day as an official holiday that year.

Leyendecker was a chief influence upon, and friend of, Norman Rockwell, who was a pallbearer at Leyendecker's funeral. In particular, the early work of Norman Rockwell for the Saturday Evening Post bears a strong superficial resemblance to that of Leyendecker. While today it is generally accepted that Norman Rockwell established the best-known visual images of Americana, in many cases they are derivative of Leyendecker's work, or reinterpretations of visual themes established by Rockwell's idol.

The visual style of Leyendecker's art inspired the graphics in The Dagger of Amon Ra, a video game, as well as designs in Team Fortress 2, a first-person shooter for the PC, Xbox 360, and PlayStation 3.[31]

Leyendecker's work inspired George Lucas and will be part of the collection of the anticipated Lucas Museum of Narrative Art.[32]

Leyendecker's Beat-up Boy, Football Hero, which appeared on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post on November 21, 1914, sold for $4.12 million on May 7, 2021.[33][34] The previous world record for a J. C. Leyendecker original was set in December 2020, when Sotheby's sold his 1930 work Carousel Ride for $516,100.[35]

Costume designer Carol Cutshall used Leyendecker's illustrations as inspiration for the costumes created for Anne Rice's Interview with the Vampire on AMC, a 2022 television series adaptation of the 1976 novel by American author Anne Rice. Of the clothing designed specifically for the male characters Louis de Pointe du Lac and Lestat de Lioncourt, Cutshall said, in part, "And the whole first two episodes, their style sense in many ways is a love letter to Leyendecker. Some things are just perfectly pulled from – like their formalwear, their tuxedos that they wear to the opera in 1917, and the black pinstripe suit with the green tie and the white boutonniere that Lestat wears to the du Lac family home for dinner – those are from a Leyendecker illustration." Cutshall also referenced Louis and Lestat's clothing being created from Leyendecker's illustrations as a way to draw a parallel between Louis and Lestat, who were shown in the series as having to keep their romantic relationship hidden from the public in the 1910s and 1920s, and Leyendecker and his life partner, Charles Beach.[36]

Films and plays

In Love with the Arrow Collar Man, a play written by Lance Ringel and directed by Chuck Muckle at Theatre 80 St. Marks from November to December 2017, dramatizes the life of Leyendecker and his life partner Charles Beach.

Coded, a 2021 film documentary, tells the story of Leyendecker and premiered at the TriBeCa Film Festival in 2021.[37]

Gallery

- Illustration for Arrow Collar ad, 1907. J. C. Leyendecker

- The Sleuth, circa 1906. Cover of the Saturday Evening Post, June 2, 1906

- Arrow Shirts ad from the 1920s

- Leyendecker illustration on cover of December 28, 1907, issue of The Saturday Evening Post

- Leyendecker illustration on for August 19, 1911, cover of The Saturday Evening Post

- Illustration for Queen Maev in Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race, 1911

- Leyendecker painting ca. 1913. Model is Charles A. Beach

- Study for the cover of The Saturday Evening Post

- J. C. Leyendecker painting for U.S. Marines recruiting poster

- Award-winning Leyendecker illustration on midsummer holiday (August 1896) issue of The Century Magazine

- U.S. Navy military recruitment poster

- Leyendecker-illustrated poster for The Pageant and Masque of St. Louis, Forest Park, May 28–31, 1914

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.