Loading AI tools

Brooklyn Dodgers fan From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

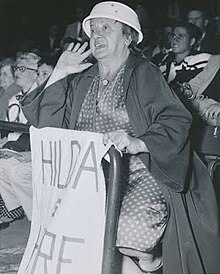

Hilda Chester (September 1, 1897 – December 1, 1978), also known as Howlin' Hilda, was an American fan of the Brooklyn Dodgers baseball team, and arguably the most famous fan in baseball history.[1]

Hilda Chester | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 1, 1897 |

| Died | December 1, 1978 (aged 81) Queens, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Mount Richmond Cemetery, Staten Island, New York, U.S. |

| Other names | Howlin' Hilda |

| Occupation | Food services employee |

| Known for | Brooklyn Dodgers fanatic |

| Children | 1 |

Chester was born on the East Side of Manhattan. She began her long allegiance to the Brooklyn Dodgers as a teenager, when she stood outside the offices of the Brooklyn Chronicle every day to hear the scores of the Dodgers' games as soon as possible. After a while, she was able to get passes to games from sportswriters. At some time, she was hired as a peanut sacker by the Harry M. Stevens corporation, which ran the concession stands at Ebbets Field and most other Major League Baseball stadiums, breaking down 50-pound sacks of peanuts into retail bags for sale.[1][2][3]

After she was done with her work, she was able to watch the games. She also worked for the Stevens' concessions at Aqueduct and Belmont Racetracks. Eventually, she "graduated" to selling hot dogs. By the 1930s, she was attending Dodgers' games frequently, and in 1938, after Larry MacPhail, the Dodgers' executive vice president, instituted Ladies' Day at Ebbets Field with a ten-cent admission price, she became a regular.[1][2][4]

Because of her extremely loud voice, thick Brooklynese accent, and allegiance to the Dodgers, Chester was well-known in Ebbets Field and beyond, throughout Brooklyn. But she became famous after her first heart attack. Instructed by her doctor not to yell anymore, she returned to Ebbets Field with a frying pan and iron ladle, and made so much noise that everybody quickly knew who she was. The Dodgers' players soon replaced her noisemaking implements with a brass cowbell as a gift. She received grandstand passes from the team, but preferred to sit in the bleachers, where she would hang a sign wherever she sat that said, "Hilda Is Here". In 1941, she had a second heart attack, and by then was important enough to be visited in Jewish Hospital of Brooklyn by Dodgers' manager Leo Durocher and several players.[5]

On one occasion, Chester influenced the events of a game, and almost its outcome. With Dodgers' pitcher Whitlow Wyatt holding a big lead, Chester dropped a folded note onto the outfield grass and yelled to Pete Reiser, "Give that to Leo!" Reiser picked up the paper, and at the end of the inning, ran in from the outfield, exchanging brief greetings with general manager Larry MacPhail, who was sitting next to the dugout. Reiser then gave the note to Durocher. It said that Wyatt was getting tired, and that Hugh Casey should start to warm up in the bullpen.[1][6]

When Wyatt gave up a hit in the next half-inning, Durocher promptly replaced him with Casey, who was then hit very hard. The Dodgers held on to win, but in the clubhouse afterward, Durocher was livid, yelling at Reiser, "Don't you ever give me another note from MacPhail as long as you play for me!" Reiser answered that the note wasn't from MacPhail, it was from Hilda. It was one of the few times Durocher was at a loss for words.[1][6]

Chester occasionally accompanied the Dodgers on short road trips. In Philadelphia, one of her counterparts for the Phillies started to yell at and berate Dixie Walker, calling him a has-been. "You're all through!" yelled the Phillies' fan. Chester quieted him with one comment. "Oh, yeah?" she yelled back. "Look where he is, and look where you are!"[1][6]

In 1943, Chester was given a silver bracelet from the Dodgers, with her first name on the band, and a small dangling silver baseball.[7]

In 1946, Chester was called as a defense witness for Durocher, who was on trial for assault. The previous year, a fan named John Christian had been heckling the Dodgers' players from the Ebbets Field grandstand many times over several weeks. On June 9, 1945, Durocher had enlisted Joseph Moore, a special policeman at the game, to get Christian from his seat, and the three met under the stands. Christian wound up with a broken jaw, and Durocher was accused of using brass knuckles to beat him up. Chester testified that Durocher had come to her aid and was defending her honor because Christian had been calling her names, including "cocksucker," and "usin' langwidge that shocked the ladies." After two days of testimony from several witnesses, including Durocher, who testified in his own defense, the jury deliberated 38 minutes and both Durocher and Moore were acquitted on April 25, 1946.[8][9][10][11]

Of all the Dodgers' players and managers, Chester was partial to Durocher because he had led the visit to the hospital when she had her heart attack in 1941. Durocher sent her cards annually at Christmas time for many years. Chester also occasionally went to Yankee Stadium and the Polo Grounds, and to Madison Square Garden to see the New York Rangers, and although her initial allegiance was with the Dodgers, she became ambivalent between the Dodgers and the New York Giants after Durocher became the Giants' manager.[2][10]

Chester appeared on the episode of This Is Your Life which celebrated the life of umpire Beans Reardon, in the Ebbets Field scene of the comedy Whistling in Brooklyn, and in Brooklyn, I Love You (1946), a Paramount Pictures short highlighting the Dodgers' 1946 season.[2][10]

The Dodgers named their all-time team in between games of their Old-Timers' Day double-header in 1955. On the occasion, they asked other significant contributors to the team who were in the stands to take bows, including Billy Herman, former star second baseman, Whit Wyatt, former star pitcher, Leon Cadore, who pitched an entire 26 inning game in 1920, Otto Miller, who was on the Dodgers' first two pennant-winning teams of the modern era, Arthur Dede, Gus Getz, Jack Doscher, three of the oldest living Dodgers, and Hilda Chester as the Dodgers' all-time fan.[12] Several weeks later, she was profiled in a newspaper article in The New York Times.[2]

After the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles following the 1957 season, Chester said she "wouldn't be caught dead" going to see them in Philadelphia, their closest visit to Brooklyn.[13]

Chester was very private about her life outside attending baseball games. Her husband died relatively early in their marriage. Their daughter, Bea Chester,[14][15] was brought up at the Brooklyn Hebrew Orphan Asylum.[10] Bea was a backup at third base in 1943 and 1944 in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League and had a son named Stephen by 1948.[16]

When the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles, Chester lost her team, her outlet to fandom, and her fame, although she continued to be a semi-celebrity for several more years. Upon the razing of Ebbets Field in 1960, she and five members of the Dodger Sym-Phony band appeared on Be Our Guest, a short-lived television program on CBS. Other guests on that episode were former Dodgers Ralph Branca and Carl Erskine, and former Phil Silvers Show regulars Maurice Gosfield and Harvey Lembeck.[17] She was also honored as "America's No. 1 baseball fan" during ceremonies at the opening of the National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita, Kansas in 1961.[10][18]

Over time, she slowly faded from the news, although she maintained some of her old ties to the Dodgers. In 1969, Dixie Walker noted that he hadn't been back to Brooklyn "for years" although he added, "but last September I got a birthday card from Hilda Chester. She never misses a one."[10][19]

Chester died on December 1, 1978. By then, she apparently was no longer in touch with or had no immediate family, and was indigent. She was buried by the Hebrew Free Burial Association in their Mount Richmond Cemetery on Staten Island. Unlike many of her antics, her death was not reported in any news media.[10]

Three years after her death, Chester's character had a minor role in The First, the Broadway musical about Jackie Robinson that was adapted from a book by Joel Siegel, with music by Bob Brush and lyrics by Martin Charnin.[20] More than 30 years later, she was the subject of a one-person biographical musical, Howling Hilda.[21] She is also remembered by the annual Hilda Award given by the Baseball Reliquary, and with a nearly life-size fabric-machê statue at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.[10]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.