Hebraization of Palestinian place names

The renaming of geographical sites in Palestine From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Hebrew-language names were coined for the place-names of Palestine throughout different periods under the British Mandate; after the establishment of Israel following the 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight and 1948 Arab–Israeli War; and subsequently in the Palestinian territories occupied by Israel in 1967.[1][2] A 1992 study counted c. 2,780 historical locations whose names were Hebraized, including 340 villages and towns, 1,000 Khirbat (ruins), 560 wadis and rivers, 380 springs, 198 mountains and hills, 50 caves, 28 castles and palaces, and 14 pools and lakes.[3] Palestinians consider the Hebraization of place-names in Palestine part of the Palestinian Nakba.[4]

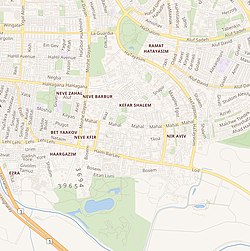

Two examples of Hebraization of Palestinian towns depopulated in 1948. In the first, Bayt Jibrin became Beit Guvrin, in the second Salama became Kfar Shalem.

Many existing place names in Palestine are based on unknown etymologies. Some are descriptive, some survivals of ancient Nabataean, Hebrew Canaanite or other names, and the occasional name was unaltered from the forms found in the Hebrew Bible or Talmud.[5][6] During classical and late antiquity, the ancient place-names metamorphosed into Aramaic and Greek,[7][8] the two major languages spoken in the region before the advent of Islam.[8][7][9] Following the Muslim conquest of the Levant, Arabized forms of the ancient names were adopted.

The Hebraization of place-names was encouraged by the Israeli government, aiming to strengthen the connection of Jews, most of whom had immigrated in recent decades, with the land.[10] As part of this process, some ancient Biblical or Talmudic place-names were restored,[11] although enthusiasm since cooled after mistakes were identified by archeologists.[12][13] Some names were adapted from Arabic,[12] including cases where Hebraizations were chosen because the Hebrew was a homophone of the Arabic despite having a different meaning.[12] In other cases sites with only Arabic names and no pre-existing ancient Hebrew names or associations were given new Hebrew names, thereby losing the historical tradition.[14][11] In some instances, the Palestinian Arabic place name was preserved in the modern Hebrew, despite there being a different Hebrew tradition regarding the name, as in the case of Banias, which in classical Hebrew writings is called Paneas.[15] Municipal direction sign-posts and maps produced by state-run agencies sometimes note the traditional Hebrew name and the traditional Arabic name alongside each other, such as "Nablus / Shechem" and "Silwan / Shiloach" etc.[16] In certain areas of Israel, particularly the mixed cities, there is a growing trend to restore the original Arabic street names that were Hebraized after 1948.[17][18]

History

Summarize

Perspective

Early history

In the 19th century, the contemporary Palestinian Arabic toponyms were used to identify ancient locations. These two examples were the most notable lists created during the period.[19]

C. R. Conder (1848–1910) of the Palestine Exploration Fund was among the first to analyze present-day Arabic place-names in order to assess what a more ancient Hebrew name may have been. Conder's contribution did not eradicate the Arabic place-names in his Survey of Western Palestine maps, but preserved their names intact, rather than attribute a site to a dubious identification.[20] In his memoirs, he mentions that the Hebrew and Arabic traditions of place-names are often consonant with each other:

The names of the old towns and villages mentioned in the Bible remain for the most part almost unchanged... The fact that each name was carefully recorded in Arabic letters made it possible to compare with the Hebrew in a scientific and scholarly manner... When the Hebrew and the Arabic are shown to contain the same radicals, the same gutturals, and often the same meanings, we have a truly reliable comparison... We have now recovered more than three-quarters of the Bible names, and are thus able to say with confidence that the Bible topography is a genuine and actual topography, the work of Hebrews familiar with the country.[21]

First modern Hebraization efforts

Modern Hebraization efforts began from the time in the First Aliyah in 1880.[23] In the early 1920s, the HeHalutz youth movement began a Hebraization program for newly established settlements in Mandatory Palestine.[24] These names, however, were applied only to sites purchased by the Jewish National Fund (JNF), as they had no sway over the names of other sites in Palestine.

Seeing that directional signposts were frequently inscribed only in the Arabic language with their English transliterations (excluding their equivalent Hebrew names), the Jewish community in Palestine, led by prominent Zionists such as David Yellin, tried to influence the naming process initiated by the Royal Geographical Society's (RGS's) Permanent Committee on Geographical Names,[23][25] so as to make the naming more inclusive.[26] Despite these efforts, well-known cities and geographical places, such as Jerusalem, Jericho, Nablus, Hebron, the Jordan River, etc. carried names in both Hebrew and Arabic writing (e.g. Jerusalem / Al Quds / Yerushalayim and Hebron / Al Khalil / Ḥevron),[27] but lesser-known classical Jewish sites of antiquity (e.g. Jish / Gush Halav; Beisan /Beit She'an; Shefar-amr / Shefarʻam; Kafr 'Inan / Kefar Hananiah; Bayt Jibrin / Beit Gubrin, etc.) remained inscribed after their Arabic names, without change or addition.[28][29][26] The main objection to adding additional spellings for ancient Hebrew toponymy was the fear that it would cause confusion to the postal service, when long accustomed names were given new names, as well as be totally at variance with the names already inscribed on maps. Therefore, British officials sought to ensure unified forms of place-names.[30]

One of the motivating factors behind members of the Yishuv to apply Hebrew names to old Arabic names, despite attempts to the contrary by the RGS Committee for Names,[26] was the belief by historical geographers, both Jewish and non-Jewish, that many Arabic place-names were mere "corruptions" of older Hebrew names[31] (e.g. Khirbet Shifat = Yodfat; Khirbet Tibneh = Timnah;[32][33] Lifta = Nephtoah;[34] Jabal al-Fureidis = Herodis, et al.). At other times, the history of assigning the "restored Hebrew name" to a site has been fraught with errors and confusion, as in the case of the ruin ʻIrâq el-Menshiyeh, situated where Kiryat Gat now stands. Initially, it was given the name Tel Gath, based on Albright's identification of the site with the biblical Gath. When this was found to be a misnomer, its name was changed to Tel Erani, which, too, was found to be an erroneous designation for what was thought to be the old namesake for the site.[35]

According to Professor Virginia Tilley, "[a] body of scientific, linguistic, literary, historical, and biblical authorities was invented to foster impressions of Jewish belonging and natural rights in a Jewish homeland reproduced from a special Jewish right to this land, which clearly has been occupied, through the millennia, by many peoples."[36]

As early as 1920, a Hebrew sub-committee was established by the British government in Palestine with the aim of advising the government on the English transcript of names of localities and in determining the form of the Hebrew names for official use by the government.[25]

JNF Naming Committee

In 1925, the Directorate of the Jewish National Fund (JNF) established The Names Committee for the Settlements, with the intent of giving names to the new Jewish settlements established on lands purchased by the JNF.[37] It was led directly by the head of the JNF, Menachem Ussishkin.[38] The Jewish National Council (JNC), for their part, met in parley in late 1931, in order to make its recommendations known to the British government in Mandatory Palestine, by suggesting emendations to a book published by the British colonial office in Palestine in which it outlined a set of standards used when referencing place-names transliterated from Arabic and Hebrew into English, or from Arabic into Hebrew, and from Hebrew into Arabic, based on the country's ancient toponymy.[39] Many of the same proposals made by the JNC were later implemented, beginning in 1949 (Committee for Geographical Names) and later following 1951, when Yeshayahu Press (a member of the JNC) established the Government Naming Committee.[40]

Meron Benvenisti writes that the Arabic geographical names upset the new Jewish community, for example on 22 April 1941 the Emeq Zevulun Settlements Committee wrote to the head office of the JNF:[41]

Such names as the following are displayed in all their glory: Karbassa, al- Sheikh Shamali, Abu Sursuq, Bustan al-Shamali – all of them names that the JNF has no interest in immortalizing in the Z'vulun Valley.... We recommend to you that you send a circular letter to all of the settlements located on JNF land in the Z'vulun Valley and its immediate vicinity and warn them against continuing the above-mentioned practice [i.e., the use of] old maps that, from various points of view, are dangerous to use.

Between 1925 and 1948, the JNF Naming Committee gave names to 215 Jewish communities in Palestine.[23] Although sweeping changes had come over the names of old geographic sites, a record of their old names is preserved on the old maps.[42]

Arabic language preeminence

By 1931, the destinational listings at post offices, signs at train stations and place-names listed in the telephone directory, had removed any mention in Hebrew of "Shechem" (Nablus), "Nazareth," and "Naḥal Sorek" (Wadi es-Sarar), which aroused the concern of the Jewish National Council that the British Government of Palestine was being prejudicial towards its Jewish citizens.[43] Naḥal Sorek, was a major route and thoroughfare when commuting by train from Jerusalem to Hartuv.

Since the establishment of the State of Israel

1949: Committee for the Designation of Place-Names in the Negev

In late 1949, after the 1947–1949 Palestine war, the new Israeli government created the Committee for the Designation of Place-Names in the Negev Region, a group of nine scholars whose job was to assign Hebrew names to towns, mountains, valleys, springs, roads, etc., in the Negev region.[44] Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion had decided on the importance of renaming in the area earlier in the year, writing in his diary in July: "We must give Hebrew names to these places – ancient names, if there are, and if not, new ones!";[45] he subsequently established the committee's objectives with a letter to the chairman of the committee:[44]

We are obliged to remove the Arabic names for reasons of state. Just as we do not recognize the Arabs' political proprietorship of the land, so also do we not recognize their spiritual proprietorship and their names.

In the Negev, 333 of the 533 new names which the committee decided upon were transliterations of, or otherwise similar-sounding to, the Arabic names.[46] According to Bevenisti, some members of the committee had objected to the eradication of Arabic place-names, but in many cases they were overruled by political and nationalistic considerations.[46]

1951: Governmental Naming Committee

In March 1951, the JNF committee and the Negev committee were merged to cover all of Israel. The new merged committee stated their belief that the "Judaization of the geographical names in our country [is] a vital issue".[47] The work was ongoing as of 1960; in February 1960 the director of the Survey of Israel, Yosef Elster, wrote that "We have ascertained that the replacement of Arabic names with Hebrew ones is not yet complete. The committee must quickly fill in what is missing, especially the names of ruins."[48] In April 1951, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi and Dr. Benjamin Maisler were appointed to the Government Naming Committee.[49]

Between 1920 and 1990, the different committees had set Hebrew names for some 7,000 natural elements in the country, of which more than 5,000 were geographical place-names, several hundred were names of historical sites, and over a thousand were names given to new settlements.[50] Vilnay has noted that, since the 19th century, biblical words, expressions and phrases have provided names for many urban and rural settlements and neighborhoods in Modern Israel.[51]

While the names of many newer Jewish settlements had replaced the names of older Arab villages and ruins (e.g. Khirbet Jurfah becoming Roglit;[52][53] Allar becoming Mata; al-Tira becoming Kfar Halutzim, which is now Bareket, etc.), leaving no traces of their former designations, Benvenisti has shown that the memorial of these ancient places had not been utterly lost through hegemonic practices:

Approximately one-quarter of the 584 Arab villages that were standing in the 1980s, had names whose origins were ancient – biblical, Hellenistic, or Aramaic.[54]

Today, the Israeli Government Naming Committee discourages giving a name to a new settlement if its name cannot be shown to be connected in some way to the immediate area or region. Still, it is the only authorized arbiter of names, whether the name has a historical connection to the site or not.[55][56]

Recent trends

By the 2010s, a trend emerged to restore the original Arabic street names which were Hebraized after 1948 in certain areas of Israel, particularly mixed Jewish–Arab cities.[17][18]

See also

Citations

General bibliography

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.