Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Haplogroup I-M253

Y chromosome haplogroup From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

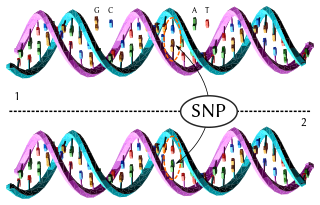

Haplogroup I-M253, also known as I1, is a Y chromosome haplogroup. The genetic markers confirmed as identifying I-M253 are the SNPs M253,M307.2/P203.2, M450/S109, P30, P40, L64, L75, L80, L81, L118, L121/S62, L123, L124/S64, L125/S65, L157.1, L186, and L187.[7] It is a primary branch of Haplogroup I-M170 (I*).

Haplogroup I1 is believed to have been present among Upper Paleolithic European hunter-gatherers as a minor lineage but due to its near-total absence in pre-Neolithic DNA samples it cannot have been very widespread. Neolithic I1 samples are very sparse as well, suggesting a rapid dispersion connected to a founder effect in the Nordic Bronze Age. Today it reaches its peak frequencies in Sweden (52 percent of males in Västra Götaland County) and western Finland (more than 50 percent in Satakunta province).[8] In terms of national averages, I-M253 is found in 38-39% of Swedish males,[9][10][8] 37% of Norwegian males,[11][12][13] 34.8% of Danish males,[14][15][16] 34.5% of Icelandic males,[17][18][19] and about 28% of Finnish males.[20] Bryan Sykes, in his 2006 book Blood of the Isles, gives the members – and the notional founding patriarch of I1 the name "Wodan".[21]

All known living members descend from a common ancestor 6 times younger than the common ancestor with I2.[1]

Before a reclassification in 2008,[22] the group was known as I1a, a name that has since been reassigned to a primary branch, haplogroup I-DF29. The other primary branches of I1 (M253) are I1b (S249/Z131) and I1c (Y18119/Z17925).

More than 99% of living men with I1 belong to the DF29 branch which is estimated to have emerged in 2400 BCE.[23][24] All DF29 men share a common ancestor born between 2500 and 2400 BCE.[25] The oldest ancient individual with I1-DF29 found is Oll009, a man from early Bronze Age Sweden.[26][27]

A 2024 study found that I1-M253 expanded rapidly during a migration from the eastern or northeastern parts of Scandinavia into Southern Sweden, Denmark and Norway around 2000 BC and was associated with the introduction of stone cist burials.[28] The study concluded that the spread of Y-DNA haplogroup I1 was associated with a genetic cluster labelled as "LNBA phase III" and that this genetic cluster formed the predominant ancestry source for Bronze Age, Iron Age and Viking Age Scandinavians, as well as other ancient European groups with a documented Scandinavian or Germanic association (for example, Anglo-Saxons and Goths; Extended Data Fig. 6e).

Remove ads

Origins

Summarize

Perspective

While haplogroup I1 most likely diverged from I* as early as 27,000 years ago in the Gravettian, so far DNA studies have only been able to locate it in three Paleolithic and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. As of November 2022, only 6 ancient DNA samples from human remains dating to earlier than the Nordic Bronze Age have been assigned to haplogroup I1:

- BAL051. A hunter-gatherer from the Azilian in Spain in 11,466 BCE classified as having a now extinct branch of I-Z2699.[24][29]

- Burial SF11 Date: 7500 BC– A Scandinavian hunter-gatherer with the label SF11 found on Stora Karlsö on Gotland. SF11 was found to have carried 9 of the 312 SNPs that define haplogroup I1. SF11 was classified as I1-Z2699*.[30][31][32][33] SF11 was not assigned to a specific archaeological culture due to the skeleton being found in the Stora Förvar cave on Stora Karlsö.

- Burial BAB5: Assumed a date of 5600-4900 BC according to archaeological context, although without C14 dating – An individual sample from Balatonszemes-Bagodomb labelled BAB5, from Hungary.[34] BAB5 was found to have carried 1 of the 312 SNPs that define haplogroup I1. BAB5 may also be classified as I1-Z2699*.[35] The skeletal remains of BAB5 have not been radiocarbon dated, and the 2015 study provides no analysis of the sample's autosomal ancestry. A 2023 study with samples from the same site features several Migration Period Langobard aDNA samples, putting doubts to the archaeological dating of sample BAB5.[36]

- Burial RISE179 Date: 2010-1776 BC – An individual found in a kurgan burial dating to the late Neolithic Dagger Period in Scandinavia labelled RISE179.[37] The grave is located close to Abbekås on the south coast of Skåne RISE179 had a genetic affinity to the populations of the Corded Ware culture and the Unetice culture.[37]

- Burial oll009 Date:1930-1750 BC - A LNBA individual from Southern Sweden. oll009 and was sequenced in the study titled "The genomic ancestry of the Scandinavian Battle Axe Culture people and their relation to the broader Corded Ware horizon".[38] Oll009 is dated to the Scandinavian late Neolithic and was found in a burial in Sweden close to Öllsjö on the east coast of Skåne. Similar to RISE179, he carried a high percentage of Western Steppe-Herder ancestry and had a genetic affinity to the population of the Battle Axe culture and other populations of the Corded Ware horizon.[39] oll009 has Y11204 but does not seem to have Y164553 or Y11205.[40]

Despite the high frequency of haplogroup I1 in present-day Scandinavians, I1 is completely absent among early agriculturalist DNA samples from Neolithic Scandinavia.[41][42][32] Except for a single DNA sample (SF11), it is also absent from Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Scandinavia. I1 first starts to appear in Scandinavia in notable frequency during the late Neolithic in conjunction with the entrance of groups carrying Western Steppe Herder ancestry into Scandinavia, but does not increase significantly in frequency until the beginning of the Nordic Bronze Age.[37][43][44]

Due to the very low number of ancient DNA samples that have been assigned to I1 that date to earlier than the Nordic Bronze Age, it is currently unknown whether I1 was present as a rare haplogroup among Scandinavian forager cultures such as Pitted Ware before becoming assimilated by the Battle Axe culture, or if it was brought into Scandinavia by incoming groups such as Battle Axe who may have assimilated it from cultures such as the Funnelbeaker culture in Central Europe; or the steppe itself. Future research will most likely be able to determine which one of these two possible origins turns out to be the case.

Samples SF11 and BAB5 are unlike other ancient DNA samples assigned to I1 in the sense that they both seem to represent now-extinct branches of I1 that hadn't fully developed into I-M253 yet. They are therefore unlikely to have been ancestral to present-day carriers of I1, who all share a common ancestor that lived around 2600 BC.

According to a study published in 2010, I-M253 originated between 3,170 and 5,000 years ago, in Chalcolithic Europe.[2] A new study in 2015 estimated the origin as between 3,470 and 5,070 years ago or between 3,180 and 3,760 years ago, using two different techniques.[3]

In 2007, it was suggested that it initially dispersed from the area that is now Denmark.[14] However, Prof. Dr. Kenneth Nordtvedt, Montana State University, regarding the MRCA, in 2009 wrote in a personal message: "We don't know where that man existed, but the greater lower Elbe basin seems like the heartland of I1".

Latest results (January 2022) published by Y-Full suggest I1 (I-M253) was formed 27,500 ybp (95 CI: 29,800 ybp – 25,200 ybp) with TMRCA 4,600 ybp (95 CI: 5,200 ybp – 4,000 ybp). Since the most up-to date calculated estimation of TMRCA of I1 is thought to be around 2600 BC, this likely puts the ancestor of all living I1 men somewhere in Northern Europe around that time. The phylogeny of I1 shows the signature of a rapid star-like expansion.[45][46] This suggests that I1 went from being a rare marker to a rather common one in a rapid burst.[3]

Remove ads

Structure

Summarize

Perspective

I-M253 (M253, M307.2/P203.2, M450/S109, P30, P40, L64, L75, L80, L81, L118, L121/S62, L123, L124/S64, L125/S65, L157.1, L186, and L187) or I1 [7]

- I-DF29 (DF29/S438); I1a

- I-CTS6364 (CTS6364/Z2336); I1a1

- FGC20030; I1a1a~

- S4767; I1a1a1~

- I-M227; I1a1a1a1a

- A394; I1a1a2~

- Y11221; I1a1a3~

- A5338; I1a1a4~

- S4767; I1a1a1~

- CTS10028; I1a1b

- I-L22 (L22/S142); I1a1b1

- CTS11651/Z2338; I1a1b1a~

- I-P109; I1a1b1a1

- I-Y3662; I1a1b1a1e~

- I-S14887; I1a1b1a1e2~

- I-Y11203; I1a1b1a1e2d~

- I-Y29630; I1a1b1a1e2d2~

- I-Y11203; I1a1b1a1e2d~

- I-S14887; I1a1b1a1e2~

- I-Y3662; I1a1b1a1e~

- CTS6017; I1a1b1a2

- I-L205 (L205.1/L939.1/S239.1); I1a1b1a3

- CTS6868; I1a1b1a4

- I-Z74; I1a1b1a4a

- CTS2208; I1a1b1a4a1~

- I-L287; I1a1b1a4a1a

- I-L258 (L258/S335); I1a1b1a4a1a1

- I-L287; I1a1b1a4a1a

- I-L813; I1a1b1a4a2

- FGC12562; I1a1b1a4a3~

- CTS2208; I1a1b1a4a1~

- I-Z74; I1a1b1a4a

- I-P109; I1a1b1a1

- CTS11603/S4744; I1a1b1b~

- I-FT40464

- I-Y19934

- I-L300 (L300/S241); I1a1b1b1a1

- I-Y31032

- I-Y32014

- I-Y22918

- I-Y21972

- I-Y24013

- I-Y24015

- I-Y31032

- I-Y19933

- I-Y19932

- I-Y22015

- I-FT57000

- I-Y22015

- I-Y19932

- I-L300 (L300/S241); I1a1b1b1a1

- I-Y19934

- I-FT40464

- CTS11651/Z2338; I1a1b1a~

- FGC10477/Y13056; I1a1b2

- A8178, A8182, A8200, A8204; I1a1b3~

- F13534.2/Y17263.2; I1a1b4~

- I-L22 (L22/S142); I1a1b1

- FGC20030; I1a1a~

- I-Z58 (S244/Z58); I1a2

- I-Z59 (S246/Z59); I1a2a

- I-Z60 (S337/Z60, S439/Z61, Z62); I1a2a1

- I-Z140 (Z140, Z141)

- I-L338

- I-F2642 (F2642)

- I-Z73

- I-L1302

- I-L573

- I-L803

- I-Z140 (Z140, Z141)

- I-Z382; I1a2a2

- I-Z60 (S337/Z60, S439/Z61, Z62); I1a2a1

- I-Z138 (S296/Z138, Z139); I1a2b

- I-Z2541

- I-Z59 (S246/Z59); I1a2a

- I-Z63 (S243/Z63); I1a3

- I-BY151; I1a3a

- I-L849.2; I1a3a1

- I-BY351; I1a3a2

- I-CTS10345

- I-Y10994

- I-Y7075

- I-CTS10345

- I-S2078

- I-S2077

- I-Y2245 (Y2245/PR683)

- I-L1237

- I-FGC9550

- I-S10360

- I-S15301

- I-Y7234

- I-L1237

- I-Y2245 (Y2245/PR683)

- I-S2077

- I-BY62 (BY62); I1a3a3

- I-BY151; I1a3a

- I-CTS6364 (CTS6364/Z2336); I1a1

- I-Z131 (Z131/S249); I1b

- I-CTS6397; I1b1

- I-Z17943 (Y18119/Z17925, S2304/Z17937); I1c

Remove ads

Historical expansion

Summarize

Perspective

Haplogroup I1, as well as subclades of R1b such as R1b-Z18 and subclades of R1a such as R1a-Z284, are strongly associated with Germanic peoples and are linked to the proto-Germanic speakers of the Nordic Bronze Age.[47][48] Current DNA research indicates that I1 was close to non-existent in most of Europe outside of Scandinavia and northern Germany before the Migration Period. The expansion of I1 is directly tied to that of the Germanic tribes. Starting around 900 BC, Germanic tribes started moving out of southern Scandinavia and northern Germany into the nearby lands between the Elbe and the Oder. Between 600 and 300 BC another wave of Germanic peoples migrated across the Baltic Sea and settled alongside the Vistula. Germanic migration to that area resulted in the formation of the Wielbark culture, which is associated with the Goths.[49]

I1-Z63 has been traced to the Kowalewko burial site in Poland which dates to the Roman Iron Age. In 2017 Polish researchers could successfully assign YDNA haplogroups to 16 individuals who were buried at the site. Out of these 16 individuals, 8 belonged to I1. In terms of subclades, three belonged to I-Z63, and in particular subclade I-L1237.[50] The Kowalewko archeological site has been associated with the Wielbark culture. Therefore, the subclade I-L1237 of I-Z63 may be seen somewhat as a genetic indicator of the Gothic tribe of late antiquity. I1-Z63 has also been found in a burial associated with Goth and Lombard remains in Collegno, Italy.[51][52] The cemetery is dated to the late 6th Century and further suggests that I1-Z63 and downstream subclades are linked to early Medieval Gothic migrations.

In 2015, a DNA study tested the Y-DNA haplogroups of 12 samples dated to 300–400 AD from Saxony-Anhalt in Germany. 8 of them belonged to haplogroup I1. This DNA evidence is in alignment with the historical migrations of Germanic tribes from Scandinavia to central Europe.[53]

Additionally, I1-Z63 was found in the Late Antiquity site Crypta Balbi in Rome, this time with the downstream subclade I-Y7234.[54] Material findings associated with the Lombards have been excavated in Crypta Balbi.

The Pla de l'Horta villa near Girona in Spain is located in close proximity to a necropolis with a series of tombs associated with the Visigoths. The grave goods and the typology of the tombs point to a Visigothic origin of the individuals. A small number of individuals buried at the site were sampled for DNA analysis in a 2019 study. One of the samples belonged to haplogroup I1.[55] This finding is in accordance with the common ancestral origin of the Visigoths and the Ostrogoths.

The Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain introduced I1 to the British Isles.[56] A 2022 study found that out of 120 samples from Anglo-Saxon period England, 41 samples or roughly 34.17% of the samples belonged to haplogroup I1. The study noted that there was a heavy correlation between "CNE" Continental North European-like ancestry and Y-DNA I1.[57]

During the Viking Age, I-M253 saw another expansion. Margaryan et al. 2020 analyzed 442 Viking world individuals from various archaeological sites in Europe. I-M253 was the most common Y-haplogroup found in the study. Norwegian and Danish Vikings brought more I1 to Britain and Ireland, while Swedish Vikings introduced it to Russia and Ukraine and brought more of it to Finland and Estonia.[58]

Remove ads

Geographical distribution

Summarize

Perspective

I-M253 is found at its highest density in Northern Europe and other countries that experienced extensive migration from Northern Europe, either in the Migration Period, the Viking Age, or modern times. It is found in all places invaded by the Norse.

During the modern era, significant I-M253 populations have also taken root in immigrant nations and former European colonies such as the United States, Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

In 2002 a paper was published by Michael E. Weale and colleagues showing genetic evidence for population differences between the English and Welsh populations, including a markedly higher level of Y-DNA haplogroup I1 in England than in Wales. They saw this as convincing evidence of Anglo-Saxon mass invasion of eastern Great Britain from northern Germany and Denmark during the Migration Period.[59] The authors assumed that populations with large proportions of haplogroup I1 originated from northern Germany or southern Scandinavia, particularly Denmark, and that their ancestors had migrated across the North Sea with Anglo-Saxon migrations and Danish Vikings. The main claim by the researchers was

that an Anglo-Saxon immigration event affecting 50–100% of the Central English male gene pool at that time is required. We note, however, that our data do not allow us to distinguish an event that simply added to the indigenous Central English male gene pool from one where indigenous males were displaced elsewhere or one where indigenous males were reduced in number ... This study shows that the Welsh border was more of a genetic barrier to Anglo-Saxon Y chromosome gene flow than the North Sea ... These results indicate that a political boundary can be more important than a geophysical one in population genetic structuring.

In 2003 a paper was published by Christian Capelli and colleagues which supported, but modified, the conclusions of Weale and colleagues.[60] This paper, which sampled Great Britain and Ireland on a grid, found a smaller difference between Welsh and English samples, with a gradual decrease in Haplogroup I1 frequency moving westwards in southern Great Britain. The results suggested to the authors that Norwegian Vikings invaders had heavily influenced the northern area of the British Isles, but that both English and mainland Scottish samples all have German/Danish influence.

Remove ads

Prominent members of I-M253

Summarize

Perspective

Through direct testing or testing of their descendants and genealogical evidence, the following notable people have been shown to be I-M253:

- Alexander Hamilton, founding father of the United States.[61]

- The Varangian Šimon, said to be the founder of the Russian Vorontsov noble family (including Prince Mikhail Semyonovich Vorontsov and Illarion Ivanovich Vorontsov-Dashkov) belonged to haplogroup I1-Y15024.[62][63][64][65]

- The Rurikid Prince Sviatopolk the Accursed (son of Vladimir the Great) belonged to I1-S2077.[66][67][68]

- Birger Jarl, Duke of Sweden of the East Geatish House of Bjälbo, founder of Stockholm; his remains were exhumed and tested in 2002 and found to be I-M253.[69] The House of Bjälbo also provided three kings of Norway, and one king of Denmark in the 14th century.

- British musician Gordon Sumner, known as Sting[70]

- William Bradford, Governor of the Plymouth Colony[71]

- William Brewster, an early colonist who emigrated to America on the Mayflower[71]

- Confederate general Robert E. Lee. Other prominent members of the Lee family of Virginia and Maryland were Richard Lee I and Richard Henry Lee.[72]

- The House of Grimaldi belong to a Scandinavian subclade of I1, downstream of I1-Y3549.[73]

- President of the United States Andrew Jackson.[74][75]

- Russian writer Leo Tolstoy.[76][77]

- Icelandic historian and poet Snorri Sturluson[76]

- Swedish scientist and theologian Emanuel Swedenborg[78][79]

- Siener van Rensburg, Boer patriotic figure and mystic.[80][81]

- Björn Wahlroos, Finnish businessman and millionaire.[76]

- Finnish mathematician Rolf Nevanlinna.[82][83][84]

- American inventor Samuel Morse.[85][86][87]

- Swedish Footballers Sebastian Larsson and his father Svante Larsson belong to I1-Y24470.[88][89][90][91]

- Swedish YouTuber Felix Kjellberg (PewDiePie) belongs to I1-L22.[92]

- Swedish actor Björn Andrésen belongs to haplogroup I1-L22.[93][94][95][96] His ancestor Johan Andrésen lived on both sides of the Swedish-Norwegian border.[97][98]

- American actor Chris Pine belongs to haplogroup I1-A13819.[99][100]

- Swedish Sámi Ice hockey player Börje Salming.[101]

- American colonist Edmund Rice.[citation needed]

- German composer Ludwig van Beethoven.[102]

Remove ads

Markers

Summarize

Perspective

The following are the technical specifications for known I-M253 haplogroup SNP and STR mutations.

Name: M253[103]

- Type: SNP

- Source: M (Peter Underhill of Stanford University)

- Position: ChrY:13532101..13532101 (+ strand)

- Position (base pair): 283

- Total size (base pairs): 400

- Length: 1

- ISOGG HG: I1

- Primer F (Forward 5′→ 3′): GCAACAATGAGGGTTTTTTTG

- Primer R (Reverse 5′→ 3′): CAGCTCCACCTCTATGCAGTTT

- YCC HG: I1

- Nucleotide alleles change (mutation): C to T

Name: M307[104]

- Type: SNP

- Source: M (Peter Underhill)

- Position: ChrY:21160339..21160339 (+ strand)

- Length: 1

- ISOGG HG: I1

- Primer F: TTATTGGCATTTCAGGAAGTG

- Primer R: GGGTGAGGCAGGAAAATAGC

- YCC HG: I1

- Nucleotide alleles change (mutation): G to A

Name: P30[105]

- Type: SNP

- Source: PS (Michael Hammer of the University of Arizona and James F. Wilson, at the University of Edinburgh)

- Position: ChrY:13006761..13006761 (+ strand)

- Length: 1

- ISOGG HG: I1

- Primer F: GGTGGGCTGTTTGAAAAAGA

- Primer R: AGCCAAATACCAGTCGTCAC

- YCC HG: I1

- Nucleotide alleles change (mutation): G to A

- Region: ARSDP

Name: P40[106]

- Type: SNP

- Source: PS (Michael Hammer and James F. Wilson)

- Position: ChrY:12994402..12994402 (+ strand)

- Length: 1

- ISOGG HG: I1

- Primer F: GGAGAAAAGGTGAGAAACC

- Primer R: GGACAAGGGGCAGATT

- YCC HG: I1

- Nucleotide alleles change (mutation): C to T

- Region: ARSDP

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads