American basketball player (1938–1987) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

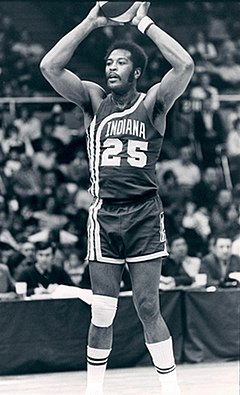

Gus (Honeycomb) Johnson Jr. (December 13, 1938 – April 29, 1987) was an American college and professional basketball player in the National Basketball Association (NBA) and American Basketball Association (NBA). A chiseled 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m), 235-pound (107 kg) forward who occasionally played center,[1] Johnson spent nine seasons with the Baltimore Bullets before he split his final campaign between the Phoenix Suns and ABA champions Indiana Pacers. He was a five-time NBA All-Star before chronic knee issues and dubious off-court habits took their tolls late in his career.

| |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | December 13, 1938 Akron, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | April 29, 1987 (aged 48) Akron, Ohio, U.S. |

| Listed height | 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m) |

| Listed weight | 230 lb (104 kg) |

| Career information | |

| High school | Central (Akron, Ohio) |

| College |

|

| NBA draft | 1963: 2nd round, 10th overall pick |

| Selected by the Chicago Zephyrs | |

| Playing career | 1963–1973 |

| Position | Power forward / small forward |

| Number | 25, 13 |

| Career history | |

| 1963–1972 | Baltimore Bullets |

| 1972 | Phoenix Suns |

| 1972–1973 | Indiana Pacers |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Career NBA and ABA statistics | |

| Points | 10,243 (16.2 ppg) |

| Rebounds | 7,624 (12.1 rpg) |

| Assists | 1,603 (2.5 apg) |

| Stats at NBA.com | |

| Stats at Basketball Reference | |

| Basketball Hall of Fame | |

Johnson was the prototype of the modern NBA power forward, a rare combination of brute strength, deceptive quickness, creative flair and startling leaping ability who played with equal flair and ferocity at both ends of the court. Well known for his frequent forays above the rim, he was among the first wave of great dunk shot artists in the game. He shattered three backboards on dunk attempts in his career, tearing down his first basket in 1964 at the Kiel Auditorium in St. Louis against the Hawks.[2] He last shattered a backboard against the Milwaukee Bucks on January 10, 1971, leaving the game with an injured wrist.[3]

Known as "The Honeycomb Kid", or "Honeycomb" for short, a nickname that his University of Idaho coach bestowed on him, Johnson was one of the colorful personalities of his era. He wore expensive shoes and Continental suits and drove a purple Bonneville convertible around town. Early in his career, he had a gold star set into one of his front teeth, which was readily seen in his friendly smile. Because as Johnson once put it, a star deserved a star.[4][5]

As a member of the Bullets, Johnson was voted to the All-Rookie Team for 1963–64, averaging 17.3 points and 13.6 rebounds per game.[6] He was named to the All-NBA Second Team four times and to the All-NBA Defense First Team on two occasions.[7] His number 25 jersey was retired by the Bullets franchise in 1986, months before his death.[8][9]

Johnson was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2010.[10]

Born amid the slums of central Akron, Ohio, Johnson was one of six children. As a teenager, Johnson spent more time at local bars and pool halls than he did libraries and book stores.[11]

"Despite my ways, I never got into any real bad trouble in Akron," Johnson recalled in a 1964 Sports Illustrated article. "I just drifted around. Nothing mattered except basketball and the Bible. I used to read the Bible all the time. I still do. I'm real big on Samson. He's helped me a lot, I suppose. He stimulates me."[12][11]

Johnson attended Akron Central High School, where he was an all-state basketball player and did well enough to graduate. Among his teammates was center Nate Thurmond, a future Hall of Fame member who towered above foes and teammates alike.[13][14] In part, that accounted for the fact that, despite his own clear talent and athletic ability, Johnson had few college athletic scholarship offers.

Johnson enrolled at hometown Akron, but he dropped out before basketball started and joined a nearby Amateur Athletic Union club. While playing for the AAU Cleveland Pipers of the National Industrial Basketball League in 1960,[15] he was spotted by a former teammate of first-year Idaho head coach Joe Cipriano. It wasn't long before the university offered him a scholarship offer. First, Johnson made a stop at Boise Junior College to improve his grades. He averaged 30 points and 20 rebounds a game for the Broncos.[16]

As a sophomore, Johnson transferred north to the University of Idaho in Moscow in 1962.[6][17] The Vandals had a .500 season at 13–13 the previous season, and the addition of Johnson made an immediate impact as they won their first five games and were 12–2 through January. Idaho was actually undefeated through January with Johnson playing: due to NCAA rules (junior college transfer originally enrolled at a four-year school) at the time, he was allowed to play regular season games only, not tournaments.[18] The Vandals went 1–2 without him at the Far West Classic in late December in Portland, and the victory was a one-pointer over WSU.[19] A week earlier with Johnson, the Vandals routed the Cougars by 37 points in Moscow.[20]

Johnson became known as "Honeycomb," a nickname Cipriano gave him because of his sweet play. As a junior, he averaged 19.0 points and 20.3 rebounds per game during the 1962–63 season, leading independent Idaho to a 20–6 record, their best in 36 years.[21] With Johnson and leading scorer Chuck White, the Vandals were at their best in their main rivalries, 4–0 versus Oregon, 4–1 versus Palouse neighbor Washington State, and 1–1 against Washington. Idaho's primary nemesis was Seattle University, led by guard Eddie Miles, who won all three of its games with the Vandals. Idaho lost its only game with Final Four-bound Oregon State at the Far West without Johnson, but won all three with Gonzaga, for a 9–3 record against its four former PCC foes and a collective 12–6 against the six Northwest rivals.[21] Attendance at the Memorial Gym was consistently over-capacity, with an estimated 3,800 for home games in the cramped facility.[22] Johnson and center Paul Silas of Creighton waged a season-long battle to lead the NCAA in rebounding. Silas claimed this by averaging 20.6 per game, 0.3 per game more than Johnson's average.[23] Johnson also set the UI record with 31 rebounds in a game against Oregon. Ducks head coach Steve Belko, a former Vandal, called Johnson a "6' 6" Bill Russell," and "the best ball player one of my teams has ever played against..."[24]

Despite their 20–6 (.769) record, the Vandals sat out the post-season. The 1963 NCAA tournament included only 25 teams, and Oregon State and Seattle were selected from the Northwest. The 1963 NIT invited only twelve teams, none from the Mountain or Pacific time zones. If the Vandals had been invited, Johnson again would not have been eligible to participate.[18]

During his time at Idaho, Johnson's standing high jump ability led the Corner Club, a local sports bar, to establish "The Nail" challenge. Anyone who could match Johnson's leap from a standing start to touch a nail hammered 11 ft 6 in (3.51 m) above the ground would win free drinks.[25] It only happened 23 years later when high jumper Joey Johnson, brother of basketball hall of famer Dennis Johnson, touched the nail.[26] Ironically, both Gus Johnson and Dennis Johnson were posthumously inducted into the hall of fame in 2010.[27]

Johnson turned professional after his only season at Idaho,[6] and Cipriano moved on to coach at Nebraska. Without Johnson (and White), the Vandals fell to 7–19 in 1963–64 and were 4–6 in the new Big Sky Conference, fifth place in the six-team league. They had a dismal 3–14 record through January and lost every game against their Northwest rivals, a collective 0–10 vs UW, WSU, UO, OSU, Seattle U., and Gonzaga.[21]

Following his professional career, Johnson returned to Moscow to help commemorate the first basketball game in the newly enclosed Kibbie Dome, held on January 21, 1976.[28][29] He participated in a pre-game alumni contest between former players of Idaho and Washington State.[30]

Johnson got a late start as an NBA player, as he turned age 25 in December of his rookie season. He was selected tenth overall (second round) of the 1963 NBA draft by the Chicago Zephyrs, who were in the process of moving to Baltimore, where they became known as the Bullets in the 1963–64 season.[31]

Johnson was an immediate starter under head coach Bob Leonard and averaged 17.3 points and 13.6 rebounds per game. Johnson finished as the runner-up for the Rookie of the Year honors to Jerry Lucas, the much-heralded Cincinnati Royals star forward and one-time Ohio State national champion and the U.S. Olympic basketball team member. Lucas and Johnson required no introduction. The two had faced each other in high school in Ohio, which marked the start of a rivalry that grew more intense at the professional level. So much so that Johnson was known to stare at a photo of Lucas as a source of motivation before their games. Johnson was selected to the NBA All-Rookie Team along with Lucas and Nate Thurmond, his one-time high school teammate.

Playing with Baltimore under Leonard, the young starting five, consisting of center Walt Bellamy (the first overall draft pick in 1961 and the 1962 rookie-of-the-year for the Chicago Zephyrs[32]), forwards Terry Dischinger (a member of the 1962-1963 all rookie team as a Chicago Zephyr[33]) and Johnson, and guards Rod Thorn and Kevin Loughery were nicknamed the "kiddie corps."[34]

Said Leonard about a young Johnson, "I could see Gussie developing into one of the great defensive forwards of all time."[34]

From the start, Johnson was both a lethal inside scorer and an exciting open-court player. During his early years, the Bullets regularly finished in last place not only in the Eastern Division but also the league. However, with good first and second-round draft choices every year, the Bullets gradually grew to be a better team, adding these players – who all made the NBA All-Rookie Team: Johnson (1963–1964), Rod Thorn (1963–1964), Wali Jones (1964–1965), Jack Marin (1966–1967), Earl Monroe (1967–1968),[33] and finally, the keystone of a championship team, Wes Unseld, who became both the Rookie-of-the-Year and the NBA Most Valuable Player for 1968–69.[35] That same year, the Bullets won the NBA Eastern Division for their very first time.[36]

Johnson was among the most effective two-way players of his time. His scoring moves around the basket were comparable to those of his peers Elgin Baylor and Connie Hawkins. Yet, however effective as Johnson was a post-up player, with his medium-range jump shot, and on the fast break, he was even more effective as an aggressive defender and a rebounder throughout his time in the NBA. Indeed, he was one of the select few players who was quick enough to be paired against backcourt great Oscar Robertson, yet strong enough to hold his own against the taller forwards of the NBA in the front line, or even be called upon to defend Wilt Chamberlain.[26]

Despite chronic knee problems that would limit his games played and shorten his career,[37][38][39][40] Johnson was a member of the NBA All-Star Team five times. During his NBA career, Johnson averaged 17.1 points and 12.7 rebounds per game.[41][7] He also scored 25 points in 25 minutes in the 1965 NBA All-Star Game.[42]

Gus Johnson had his best years with the Bullets from 1968 to 1971, including the watershed basketball year of 1968–69. While the Bullets improved, Johnson received more recognition from the press and the spectators for his outstanding play at forward. He was voted onto the All-NBA second-team during this time span. During the 1968–69 season, the Bullets achieved their best regular-season record but were quickly swept out of the playoffs by the Knicks, largely because Johnson was sidelined during the playoff series with an injury.

After fading to third place in the Eastern Division in 1969–70, Johnson played a key role in Baltimore's unexpected run to the Finals the following season by averaging 13 points and 10.4 rebounds per playoff game.[43] First, the Bullets beat the Philadelphia 76ers in a grueling seven game semifinals series, then they upset the top-seeded and defending champion New York Knicks four games to three in the Eastern Conference Finals, and advanced to the NBA Finals. But injuries had decimated the team, and the Bullets were swept in four straight by the Milwaukee Bucks, led by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Robertson, and Bobby Dandridge.

Injuries kept Johnson on the bench for most of 1971–72, limiting him to 39 games and 6 points per game. That season would be his last with the Bullets; the team would trade for Elvin Hayes the following summer. In nine seasons with Baltimore, he averaged 17.5 points, 12.9 rebounds, 2.9 assists and 35.2 minutes in 560 games.[1]

Johnson was traded to the Phoenix Suns on April 12, 1972, completing a transaction from two days prior when the Bullets acquired a second-round pick (25th overall) in the 1972 NBA draft and selected Tom Patterson.[44][45] Johnson played 21 games before being waived on December 1. He averaged 7.8 points and 6.5 rebounds in 19.9 minutes under head coaches Butch van Breda Kolff (fired after seven games) and Jerry Colangelo, Johnson's former Baltimore teammate.[1]

The Indiana Pacers, then of the American Basketball Association (ABA), picked up Johnson after he was recruited to the Pacers by one of his former Baltimore coaches, Hall of Fame inductee Slick Leonard. He played his first game with the Pacers on December 16, 1972, and became a steadying veteran influence on a young team which went on to win the 1973 ABA championship.[46][13]

"It doesn't hurt to have some veterans around, and Gus was great for team chemistry," Leonard said of adding Johnson to the Pacers.[34]

Playing in 50 games with the Pacers, and reunited with his former Coach Slick Leonard, Johnson averaged 6.0 points and 4.9 rebounds, playing alongside 22 year-old future Hall of Famer George McGinnis, Hall of Famer Mel Daniels, Hall of Famer Roger Brown, Freddie Lewis, Donnie Freeman, Darnell Hillman and Billy Keller.[47]

"Gus came to us at the end of his career when he had lost a lot of his physical abilities, but he really wanted a shot at making a run at a championship," recalled Darnell Hillman of Johnson's influence on the Pacers. "And his coming to the team made us that much more solid. He was a great, great individual. The locker room was where he was really an asset. He always knew the right things to say and he could read people. He knew who would be a little bit off or down and he could just bring you right back into focus and send you out on the floor. He was also very instrumental in being like an assistant coach to Slick on the bench. Sometimes when Slick didn't go to the assistant coach, he'd ask Gus."[48]

In the ABA playoffs, Johnson and the Pacers defeated the Denver Rockets and Ralph Simpson 4–1 and the Utah Stars with Hall of Famer Zelmo Beaty and ironman Ron Boone 4–2 to advance to the ABA Finals against the Kentucky Colonels with Hall of Famers Artis Gilmore, Dan Issel and Louie Dampier.[49][50]

The Pacers defeated the Colonels 4–3 in the 1973 ABA Finals to capture the ABA championship, with Johnson playing 13 minutes and grabbing 6 rebounds in the decisive Game 7, an 88–81 Pacers victory at Freedom Hall in Louisville, Kentucky. When Indiana center Daniels was in foul trouble toward the end of Game 7, even with his bad knees, the 35-year old Johnson was called off the bench to defend Kentucky's Gilmore. Johnson successfully did so, even though Gilmore was 7'2" tall and 11 years younger than Johnson. It was Johnson's final career game. Overall, Johnson averaged 2.7 points and 4.0 rebounds in the Finals off the bench.[51][52][53]

Injuries limited Johnson's pro basketball career to 10 seasons.

Shortly before his death from inoperable brain cancer, his jersey number 25 was retired by the Washington Bullets on his 48th birthday.[54] Upon Johnson's death, Bullets owner Abe Pollin remarked "Gus was the Dr. J of his time, and anyone who had the privilege of seeing him play will never forget what a great basketball player Gus Johnson was."[55]

A month later he was also honored by the two college programs he played for, Boise State and Idaho, during a conference basketball game between the two teams on January 17, 1987. A crowd of 12,225 at the BSU Pavilion in Boise set a Big Sky attendance record for a regular season game, and the visiting Vandals overcame an eight-point deficit in the second half to win by ten.[56] That month in a ceremony in Akron, his No. 43 was retired by Idaho, the first basketball number retired in school history.[21][57]

Before his death and reflecting on his career, Johnson had expressed that his greatest fear was that he would die and his daughters "don't even know what their daddy did."[58]

Johnson died less than four months later at Akron City Hospital on April 29, 1987, at the age of 48, and is buried at Mount Peace Cemetery in Akron. He was survived by his four daughters.[54][59]

Teammate and hall of famer Earl Monroe said of Gus Johnson – "Gus was ahead of his time, flying through the air for slam dunks, breaking backboards and throwing full-court passes behind his back. He was spectacular, but he also did the nitty gritty jobs, defense and rebounding. With all the guys in the Hall of Fame, Gus deserves to be there already."[8][9][53]

"I first saw Gus on television...I had never seen a player dominate a game so. Gus was the Dr. J of his time and anyone that ever had the privilege to see him play will never forget what a great basketball player Gus Johnson was." – Abe Pollin – Former Owner of the Washington Bullets/Wizards Franchise.[8]

New York Knicks Hall of Fame coach Red Holzman thought Johnson was superior to Michael Jordan or Julius Erving in leaping to dunk from the foul line because Johnson did not need an extra step to generate momentum.[60]

"Gus Johnson was one of the greatest players I ever played with or against," teammate and hall of famer Wes Unseld said. "He was a ferocious defender and rebounder, and as a young player, I was completely in awe of his ability. He was truly a star ahead of his time."[11]

"Gus was probably one of the roughest players I have ever played against. He was not a dirty player. He was one of the most tenacious competitors ever to play the game." – Hall of Famer Dave DeBusschere.[8][9]

“If he played today, ol’ Gussie would be a human highlight film,” said hall of famer Slick Leonard of Johnson. “That’s what people remember the most. But there was a lot more to his game than the spectacular dunks. He was special. He could play, man.”[61]

Oscar Robertson, a member of the NBA's 75th Anniversary Team that included the leagues 76 greatest players,[62] described Johnson as "'one of the truly great forwards of our time,' ... and one of the best rebounders I’ve ever seen in my life.'”[53]

Paul Silas, who was Johnson' rebounding rival in college, and an NBA player and coach, was on the court for the St. Louis Hawks in 1964 when Johnson tore down the basket while dunking. Silas has described Johnson as "tremendously gifted", with great jumping ability and strength, who did not fear contact.[53]

| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

| † | Denotes seasons in which Johnson won an ABA championship |

| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1963–64 | Baltimore | 78 | – | 36.5 | .430 | – | .658 | 13.6 | 2.2 | – | – | 17.3 |

| 1964–65 | Baltimore | 76 | – | 38.1 | .418 | – | .676 | 13.0 | 3.6 | – | – | 18.6 |

| 1965–66 | Baltimore | 41 | – | 31.3 | .413 | – | .736 | 13.3 | 2.8 | – | – | 16.5 |

| 1966–67 | Baltimore | 73 | – | 36.0 | .450 | – | .708 | 11.7 | 2.7 | – | – | 20.7 |

| 1967–68 | Baltimore | 60 | – | 37.9 | .467 | – | .667 | 13.0 | 2.7 | – | – | 19.1 |

| 1968–69 | Baltimore | 49 | – | 34.1 | .459 | – | .717 | 11.6 | 2.0 | – | – | 17.9 |

| 1969–70 | Baltimore | 78 | – | 37.4 | .451 | – | .724 | 13.9 | 3.4 | – | – | 17.3 |

| 1970–71 | Baltimore | 66 | – | 38.5 | .453 | – | .738 | 17.1 | 2.9 | – | – | 18.2 |

| 1971–72 | Baltimore | 39 | – | 17.1 | .383 | – | .683 | 5.8 | 1.3 | – | – | 6.4 |

| 1972–73 | Phoenix | 21 | – | 19.9 | .381 | – | .694 | 6.5 | 1.5 | – | – | 7.8 |

| 1972–73† | Indiana (ABA) | 50 | – | 15.1 | .441 | .190 | .738 | 4.9 | 1.2 | – | – | 6.0 |

| Career | 631 | – | 33.1 | .440 | .190 | .700 | 12.1 | 2.5 | – | – | 16.2 | |

| All-Star | 5 | 0 | 19.8 | .429 | – | .760 | 7.0 | 1.2 | – | – | 13.4 | |

| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1965 | Baltimore | 10 | – | 37.7 | .358 | – | .739 | 11.1 | 3.4 | – | – | 15.8 |

| 1966 | Baltimore | 1 | – | 8.0 | .250 | – | – | .0 | .0 | – | – | 2.0 |

| 1970 | Baltimore | 7 | – | 42.6 | .459 | – | .794 | 11.4 | 1.3 | – | – | 18.4 |

| 1971 | Baltimore | 11 | – | 33.2 | .422 | – | .745 | 10.4 | 2.7 | – | – | 13.0 |

| 1972 | Baltimore | 5 | – | 15.4 | .300 | – | 1.000 | 5.0 | .6 | – | – | 4.0 |

| 1973† | Indiana (ABA) | 17 | – | 10.8 | .254 | .000 | .750 | 4.1 | .9 | – | – | 2.5 |

| Career | 51 | – | 25.7 | .380 | .000 | .759 | 7.8 | 1.8 | – | – | 9.7 | |

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.