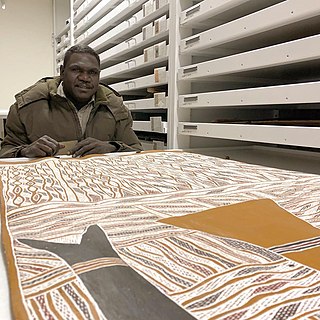

Gunybi Ganambarr

Australian Aboriginal Artist From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Gunybi Ganambarr is an Aboriginal artist from Yirrkala, in the North-eastern Arnhem Land of the Northern Territory.[1] He currently resides in Gängän where he continues to create his art.[2] Ganambarr is considered the founder of the "Found" movement in northeast Arnhem Land, in which artists use recycled materials, onto which are etched sacred designs more commonly painted on eucalyptus bark.[3]

Personal life

Summarize

Perspective

Gunybi Ganambarr was born on 15 April 1973.[2] His homeland being Yangunbi, an area on the Western shore of Melville Bay, close to where the Giddy River meets the Arafura Sea.[4] He is part of the Ngaymil Clan of the Dhuwa Moiety.[2] Dhuwa being one of the two moieties that make up the Yolngu world, where everything, including people, creatures, and vegetation, are either one or the other.[5] Ganambarr claimed that becoming an artist has allowed him to care more about educating others. He wants everyone to hear his story as he shares about his special home that has existed for thousands and thousands of years.[6]

Ganambarr plays the ceremonial yidaki, also known as a Didgeridoo.[2] In this role, he was sought after by elders to accompany their sacred song.[7] He played the Digeridoo for two of his mother's clans in Dhaḻwaŋu and Maḏarrpa ceremonies, both clans being of the Yirritja moeity.[8][9] Ganambarr spent over a decade as a construction worker and builder for the Laynhapuy Homelands Association, however returned to Gängän, his mother's homeland, later.[2] His mother being a member of the Dhaḻwaŋu clan.[2] The leaders of Ganambarr's mother's clans recognized his talents in ceremony and guided him to become a djunggaya, a caretaker of clan laws, but first encouraged him to share his knowledge through painting.[8]

One of his influential mentors is Djambawa Marawili, whose daughter, Lamangirra Marawili, he is married to.[2]

Ganambarr's upbringing was highlighted by his cultural experience in the art center in Yirrkala; it provides an economy that is inherited by everyone who lives in Arnhem Land. This pathway is clean-cut and allows each individual that enters it to be a well-known artist; anyone can tap into it. Ganambarr explained that any average individual without previous artistic and creative experience can come in with small prints that hold no value, that are now hanging in well-renowned museums around the world. This explanation reveals that the skill set in the community can be adopted by any individual, it is everyone's birthright, just as it was Gunybi's.[6]

Artistic career

Summarize

Perspective

In his return to Gängän he worked under the authority of the artists Gawirrin Gumana and Yumutjin Wunungmurra and it was precisely this that would lead him to having ceremonial authority within the Dhaḻwaŋu clan.[2] He took the cultural and sacred customs very seriously and has kept those elements strong throughout his art regardless of his modern and experimental approach.[2] He has combined that experience with a startling innovative flair to produce groundbreaking sacred art that is at once novel and still entirely consistent with Yolgnu Madayin law.[10] After working at a building cite in Arnhem Land, building houses, he was able to understand the machinery, grinder, and tools that the artists typically use to collect their bark. Ganambarr gained knowledge from his family, as artist technique was passed down and inherited through generational family ties[6]

Ganambarr began painting at the age of 30.[11] He started his career painting with natural pigments on eucalyptus bark and larrakitj, however through personal investigation and practice would begin to work with reclaimed materials, such as glass, rubber, and even various metals, pushing the boundaries on what Aboriginal art is.[1] He began experimenting with reclaimed materials in 2006.[12] Before Ganambarr's efforts to introduce reclaimed materials into the Aboriginal art scene, most Yolngu artists had been held to the longstanding tradition that in order to paint Madayin miny'tji, or sacred clan designs, one had to use materials that came from country or naturally occurred in the landscape—traditionally, these materials included natural ochres and eucalyptus bark.[13] Ganambarr consulted with his clan elders, arguing that reclaimed or "found" materials such as aluminum metal scraps should also be considered part of the land and therefore eligible for use in artwork depicting sacred designs, opening up avenues for other artists to use new materials in their artwork as well.[13] It is important to note that these reclaimed materials must be found already discarded within the landscape. Ganambarr and followers of the "Found" art movement do not buy new materials, but rather find it discarded or pre-used in some way, for example, discarded roofing insulation or sheet metal.[14] His use of discarded materials in his artworks can be traced to his twelve-year stint as a housebuilder in a Gangan outstation.[11] When asked what led Ganambarr to become an artist, he noted that he wanted to come up with a new technique and new talent[6]

In 2005 he entered the National Sculpture Prize, on invitation by National Gallery of Australia's, Brenda Croft.[2]

In 2008 he won the Xstrata Coal Engineering Indigenous Artist Award, at the Gallery of Modern Art at Queensland Art Gallery.[2]

In 2009 Ganambarr had his first solo exhibition at Annandale Galleries, titled Dhuwa Saltwater.[3] While his work never strays from the tradition of the Yolnu people, he uses his western influence to innovate what it means to make bark art.[3] The exhibition included works where the bark was incised and the remaining shavings added on after, a method not seen before.[15] Dhuwa Saltwater, was Ganambarr's place to really show himself as a revolutionary.[15]

In 2011 he won the West Australian Indigenous Art Award.[2] Within the same year, he also won an allocation in the form of a grant from the Sidney Myer Fund, which he shared with 12 other artists.[16]

In 2012 he would host his second solo exhibition at the Annandale Galleries titled, From My Mind, in which he had works containing chicken wire, roofing insulation and even PVC pipes.[17] He has on countless occasion provoked the idea of breaking the mold and instilling the question as to what is stopping Aboriginal artists from bringing in certain materials.[17] Ganambarr with ease introduced the concept of varying textures.[17]

In 2018 Ganambarr was awarded first prize in the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards for his etched aluminum work Buyku. Speaking on the work, Ganambarr said:

Artworks of this nature have multiple layers of metaphor and meaning which give lessons about the connections between an individual and specific pieces of country (both land and sea), as well as the connections between various clans but also explaining the forces that act upon and within the environment and the mechanics of a spirit’s path through existence. The knowledge referred to by this imagery deepens in complexity and secrecy as a person progresses through a life-long learning process.[18]

"Yolgnu arist Gunybi Ganambarr's innovative substitution of industrial laminate board for organic materials has transformed the centuries-old tradition of Arnhem Land bark painting, both materially and conceptually."[19]

Ganambarr said his art is inspired by mapping his family, habit, and place, which is the meaning behind his art.[6]

Collections

Art Gallery of New South Wales[20]

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College[21]

Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia[22]

Exhibitions

Summarize

Perspective

- Young Guns II (16 April - 10 May 2008)[25]

- Breaking Boundaries: Contemporary Indigenous Australian Art From The Collection (13 December - 25 October 2009)[26]

- Gunybi Ganambarr, Dhua Saltwater (28 October - 5 December 2009)[27]

- Yalmakany & Gurrundul Marawili (17 March - 17 April 2010)[28]

- Gunybi Ganambarr, From My Mind (2 May - 16 June 2012)[29]

- unDisclosed: 2nd National Indigenous Art Triennial (11 May - 22 July 2012)[30]

- Stock Jewels, Artists of the Gallery (19 June - 14 July 2012)[31]

- unDisclosed: 2nd National Indigenous Art Triennial (3 May - 5 July 2013)[30]

- Found Gunybi Ganambarr, Djirrirra Wunungmurra & Ralwurrandji Wanambi (23 July - 31 August 2013)[32]

"Found is an exhibition that explores limits."[14] Inspired by Gunybi Ganambarr, permission was granted to his fellow artists to use whatever materials catch their eye. While this is not seen as abandoning the traditional medium of bark, they are expanding their methods and materials with this exhibition.[14]

- unDisclosed: 2nd National Indigenous Art Triennial (25 October 2013 – 5 January 2014)[30]

- Celebration 25 Years of the AGWA Foundation (21 June - 1 December 2014)[33]

- Gunybi Ganambarr, Garawan Wanambi, Naminapu Maymuru-White: Notions of Country (3 November - 2 December 2017)[34]

- Artists of the Gallery (3 July - 3 August 2018)[35]

- Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka: Mittji (26 September - 26 October 2019)[36]

- Gunybi Ganambarr: Mother and Child (12 October - 1 December 2019)[37]

- Tarnanthi (18 October 2019 – 27 January 2020)[38]

- Steel: Art Design Architecture (7 December 2019 – 9 February 2020)[39]

- Special Selection, International, Australian & Aboriginal Paintings & Sculpture (8–29 August 2020)[40]

- Gunybi Ganambarr, Dhanun nalma - Here we are (7 November - 19 December 2020)[41]

- An Alternative Economics (7 May - 9 July 2022)[42]

- Transitions (20 August 2022 – 18 July 2023)[43]

- First Nation Australia (2 February - 22 March 2024)[44]

- Maḏayin: Eight Decades of Aboriginal Australian Bark Painting from Yirrkala (September 2022 – Present)[45]

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.