Greenback (1860s money)

Paper currency issued by the United States during the American Civil War From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Greenbacks were emergency paper currency issued by the United States during the American Civil War that were printed in green on the back.[1] They were in two forms: Demand Notes, issued in 1861–1862,[1] and United States Notes, issued in 1862–1865.[2] A form of fiat money, the notes were legal tender for most purposes and carried varying promises of eventual payment in coin but were not backed by existing gold or silver reserves.[3]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

Image of one dollar "Greenback", first issued in 1862

History

Summarize

Perspective

Background

Before the Civil War, the United States used gold and silver coins as its official currency. Paper currency in the form of banknotes was issued by privately owned banks, the notes being redeemable for specie at the bank's office. If a bank failed, its notes became worthless. The federal government sometimes issued Treasury Notes to borrow money during periods of economic distress, but proposals for a federal paper currency were politically contentious and recalled the experience of the Continental dollars issued during the American Revolution. These were nominally payable in silver, but rapidly depreciated due to British counterfeiting and the Continental Congress's difficulty in collecting money from the states.

The Buchanan administration had run chronic deficits as the country weathered the Panic of 1857. The southern secession movement worsened the situation, as the government lost substantial tax revenue.[4] It continued to operate during the presidential transition on private bank loans at rates up to 12 percent, with some banks asking as much as 36.[5] Salmon P. Chase, as the Treasury secretary of the incoming Lincoln administration, found the banks more receptive but struggled to keep enough coins in the Treasury to meet expenditures.[6]

Demand Notes

The United States Demand Note was authorized by Congress on July 17, 1861, and issued on August 10, 1861.

The first measure to finance the war occurred in July 1861, when Congress authorized $50,000,000 (~$1.33 billion in 2023) in Demand Notes. They bore no interest but could be redeemed for specie "on demand." Unlike state and some private banknotes, Demand Notes were printed on both sides. The reverse side was printed in green ink, so Demand Notes were dubbed "greenbacks." Initially, they were discounted relative to gold, but being fully redeemable in gold, they were soon at par. In December 1861, the government had to suspend redemption, and the Demand Notes declined.

On 1862-02-25, Congress passed the First Legal Tender Act, turning United States Notes into legal tender, with two exceptions: They could not be used to pay customs duties, or interest on the public debt. These could be paid only with gold and Demand Notes. Importers, therefore, continued to use Demand Notes in place of gold. But public confusion about the legal tender status of United States Notes continued until 1862-03-17, when Congress passed "An Act to authorize the Purchase of Coin, and for other purposes". Section 2 of that act said:

That the Treasury notes heretofore issued under the authority of the acts of July seventeen and August five, eighteen hundred and sixty-one, shall be lawful money and a legal tender in payment of all debts, public and private, within the United States, except duties on imports and interest as aforesaid.

This made the United States Notes' two legal tender payment exceptions, import duties & public debt interest payments, clear to the public. Import duties were a large part of the U.S. federal tax base at the time. Because Demand Notes were still backed by a promise of redeemability in gold (even though the U.S. Government did not physically possess enough gold to redeem the entire float of all Demand Notes all at once, the promise of an eventual redemption in gold was still backed by the power of the government), and because United States Notes had these 2 tender exceptions, Demand Notes retained superior economic value. This caused speculators to hoard the circulating Demand Notes, and as Demand Notes were used to pay import duties, they were taken out of circulation. By mid-summer of 1862, Demand Notes were available for an 8% premium over United States Notes. Newspapers were reporting on the falling amount of Demand Notes still left in circulation. By December it was estimated that the supply would soon be exhausted and that importers would have no option but gold for paying import duties.[7] When the supply of Demand Notes had been nearly exhausted they commanded a price at parity with or at only a slight discount to gold dollars[8] despite the fact that the latter continued to command a steep premium to United States Notes through the 1870s.

By June 30, 1863, only $3,300,000 of Demand Notes were outstanding versus almost $400,000,000 of Legal Tender Notes.[8] By June 30, 1883 just $58,985 remained on the books of the treasury.[9]

United States Notes

The number of Demand Notes issued was far insufficient to meet the war expenses of the government but even so was not supportable. The solution came from Colonel Edmund Dick Taylor, a businessman who was serving as a volunteer officer. Taylor met with Lincoln in January 1862 and suggested issuing unbacked paper money.[10] On February 25, 1862, Congress passed the first Legal Tender Act, which authorized the issuance of $150 million (~$3.57 billion in 2023) in United States Notes.[11]

Since the reverse of the notes was printed with green ink, they were called "greenbacks" by the public and considered to be equivalent to the Demand Notes, which were already known as such. The United States Notes were issued by the United States to pay for labor and goods.[12]

California and Oregon defied the Legal Tender Act. Gold was more available on the West Coast, and merchants in those states did not want to accept U.S. Notes at face value. They blacklisted people who tried to use them at face value. California banks would not accept greenbacks for deposit, and the state would not accept them for payment of taxes. Both states ruled that greenbacks were a violation of their state constitutions.[13]

As the government issued hundreds of millions in greenbacks, their value against gold declined. The decline was substantial, but was nothing like the collapse of the continental dollar.

In 1862, the greenback declined against gold until by December, gold had become at a 29% premium. By spring of 1863, the greenback declined further, to 152 against 100 dollars in gold. However, after the Union victory at Gettysburg, the greenback recovered to 131 dollars to 100 in gold. In 1864, it declined again, as Grant was making little progress against Lee, who held strong in Richmond throughout most of the war. The greenback's low point came in July that year, with 258 greenbacks equal to 100 gold. When the war ended in April 1865 the greenback made another recovery to 150.[14] The recovery began when Congress limited the total issue of greenback dollars to $450 million. The greenbacks rose in value until December 1878, when they became on par with gold. Greenbacks then became freely convertible into gold.[15]

Complete set of 1862–63 greenbacks

| Issue | Date[16] | Denominations |

|---|---|---|

| First | March 10, 1862 | $5, $10, $20 |

| Second | August 1, 1862 | $1 & $2 |

| Third | March 10, 1863 | $50 to $1,000 |

| Obligation | Obligation text[16] |

|---|---|

| First | This note is a legal tender for all debts, public and private, except duties on imports and interest on the public debt, and is exchangeable for the U.S. six percent twenty-year bonds, redeemable at the pleasure of the United States after five years. |

| Second | This note is a legal tender for all debts, public and private, except duties on imports and interest on the public debt, and is receivable in payment of all loans made to the United States. |

| Value | Year | Obligation | Fr. | Image | Portrait[nb 1] | Population[nb 2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $1 | 1862 | Second[nb 3] | Fr.16c |  |

Salmon P. Chase (Joseph P. Ourdan)[18] | 2,607 (194) |

| $2 | 1862 | Second | Fr.41 |  |

Alexander Hamilton | 1,212 (881) |

| $5 | 1862 | First | Fr.61a |  |

Freedom (Owen G. Hanks, eng; Thomas Crawford, art)[19] Alexander Hamilton | 1,591 (188) |

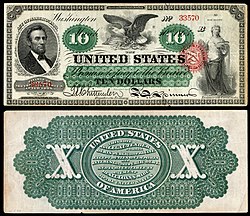

| $10 | 1863 | First | Fr.95b |  |

Abraham Lincoln (Frederick Girsch);[20] Eagle; Art | 375 (161) |

| $20 | 1863 | First | Fr.126b |  |

Liberty | 375 (161) |

| $50 | 1862 | Third | Fr.148a |  |

Alexander Hamilton (Joseph P. Ourdan)[21] | 45 (1) |

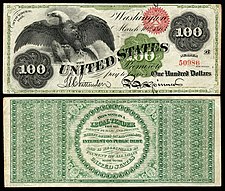

| $100 | 1863 | Third | Fr.167 |  |

Vignette spread eagle (Joseph P. Ourdan)[22] | 51 (2) |

| $500 | 1862 | Third | Fr.183c |  |

Albert Gallatin | 6 (4) |

| $1,000 | 1863 | Third | Fr.186e |  |

Robert Morris (Charles Schlecht) | 4 (1) |

See also

Notes

- Names in parentheses are either the engravers or artists responsible for the concept and/or initial design.

- The first number represents the total population[clarification needed] for the design type, the second number (in parentheses) is the total number of notes known for the variety illustrated in the table.

References

Sources

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.