Gothic language

Extinct East Germanic language From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Gothic is an extinct East Germanic language that was spoken by the Goths. It is known primarily from the Codex Argenteus, a 6th-century copy of a 4th-century Bible translation, and is the only East Germanic language with a sizeable text corpus. All others, including Burgundian and Vandalic, are known, if at all, only from proper names that survived in historical accounts, and from loanwords in other, mainly Romance, languages.

This article has an unclear citation style. The reason given is: article uses predominantly full citations but also some short ones. Move the short to full citations. (January 2025) |

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{langx}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (April 2025) |

| Gothic | |

|---|---|

The Codex Argenteus, a 6th-century Gothic manuscript | |

| Region | Oium, Dacia, Pannonia, Dalmatia, Italy, Gallia Narbonensis, Gallia Aquitania, Hispania, Crimea, North Caucasus |

| Era | attested 3rd–10th century; related dialects survived until 18th century in Crimea |

| Dialects | |

| Gothic alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | got |

| ISO 639-3 | got |

| Glottolog | goth1244 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ADA |

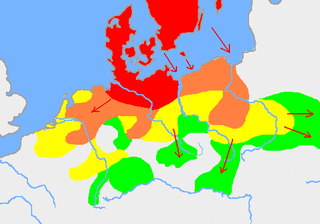

Settlements before 750 BC

New settlements by 500 BC

New settlements by 250 BC

New settlements by AD 1

Some sources also give a date of 750 BC for the earliest expansion out of southern Scandinavia and northern Germany along the North Sea coast towards the mouth of the Rhine.[3]As a Germanic language, Gothic is a part of the Indo-European language family. It is the earliest Germanic language that is attested in any sizable texts, but it lacks any modern descendants. The oldest documents in Gothic date back to the fourth century. The language was in decline by the mid-sixth century, partly because of the military defeat of the Goths at the hands of the Franks, the elimination of the Goths in Italy, and geographic isolation (in Spain, the Gothic language lost its last and probably already declining function as a church language when the Visigoths converted from Arianism to Nicene Christianity in 589).[4] The language survived as a domestic language in the Iberian Peninsula (modern-day Spain and Portugal) as late as the eighth century. Gothic-seeming terms are found in manuscripts subsequent to this date, but these may or may not belong to the same language.

A language known as Crimean Gothic survived in the lower Danube area and in isolated mountain regions in Crimea as late as the second half of the 18th century. Lacking certain sound changes characteristic of Gothic, however, Crimean Gothic cannot be a lineal descendant of the language attested in the Codex Argenteus.[5][6]

The existence of such early attested texts makes Gothic a language of considerable interest in comparative linguistics.

History and evidence

Summarize

Perspective

Only a few documents in Gothic have survived – not enough for a complete reconstruction of the language. Most Gothic-language sources are translations or glosses of other languages (namely, Greek), so foreign linguistic elements most certainly influenced the texts. These are the primary sources:

- The largest body of surviving documentation consists of various codices, mostly from the sixth century, copying the Bible translation that was commissioned by the Arian bishop Ulfilas (Wulfila, 311–382), leader of a community of Visigothic Christians in the Roman province of Moesia (modern-day Serbia, Bulgaria/Romania). He commissioned a translation into the Gothic language of the Greek Bible, of which translation roughly three-quarters of the New Testament and some fragments of the Old Testament have survived. The extant translated texts, produced by several scholars, are collected in the following codices and in one inscription:

- Codex Argenteus (Uppsala), including the Speyer fragment: 188 leaves

The best-preserved Gothic manuscript, dating from the sixth century, it was preserved and transmitted by northern Ostrogoths in modern-day Italy. It contains a large portion of the four gospels. Since it is a translation from Greek, the language of the Codex Argenteus is replete with borrowed Greek words and Greek usages. The syntax in particular is often copied directly from the Greek.

- Codex Ambrosianus (Milan) and the Codex Taurinensis (Turin): Five parts, totaling 193 leaves

It contains scattered passages from the New Testament (including parts of the gospels and the Epistles), from the Old Testament (Nehemiah), and some commentaries known as Skeireins. The text likely had been somewhat modified by copyists.

- Codex Gissensis (Gießen): One leaf with fragments of Luke 23–24 (apparently a Gothic-Latin diglot) was found in an excavation in Arsinoë in Egypt in 1907 and was destroyed by water damage in 1945, after copies had already been made by researchers.

- Codex Carolinus (Wolfenbüttel): Four leaves, fragments of Romans 11–15 (a Gothic-Latin diglot).

- Codex Vaticanus Latinus 5750 (Vatican City): Three leaves, pages 57–58, 59–60, and 61–62 of the Skeireins. This is a fragment of Codex Ambrosianus E.

- Gothica Bononiensia (also known as the Codex Bononiensis or "Bologna fragment"), a palimpsest fragment, discovered in 2009, of two folios with what appears to be a sermon, containing besides non-biblical text a number of direct Bible quotes and allusions, both from previously attested parts of the Gothic Bible (the text is clearly taken from Ulfilas's translation) and from previously unattested ones (e.g., Psalms, Genesis).[7]

- Fragmenta Pannonica (also known as the Hács-Béndekpuszta fragments or Tabella Hungarica), which consist of fragments of a 1 mm thick lead plate with remnants of verses from the Gospels.

- The Mangup Graffiti: five inscriptions written in the Gothic alphabet discovered in 2015 from the basilica church of Mangup, Crimea. The graffiti all date from the mid-9th century, making this perhaps the youngest attestation of the Gothic alphabet (being seemingly slightly more recent than the two Carolingian alphabets listed below). The five texts include a quotation from the otherwise unattested Psalm 76 and some prayers; the language is not noticeably different from Wulfila's and only contains words known from other parts of the Gothic Bible.[8]

- Codex Argenteus (Uppsala), including the Speyer fragment: 188 leaves

- A scattering of minor fragments: two deeds (the Naples and Arezzo deeds, on papyri), two Carolingian-era Gothic alphabets recorded in otherwise non-Gothic manuscripts (respectively the late eighth to early ninth century Gothica Vindobonensia[9] and the ninth-century Gothica Parisina[10]), a calendar (in the Codex Ambrosianus A), glosses found in a number of manuscripts and a few runic inscriptions (between three and 13) that are known or suspected to be Gothic: some scholars believe that these inscriptions are not at all Gothic.[11] Krause thought that several names in an Indian inscription were possibly Gothic.[12]

Reports of the discovery of other parts of Ulfilas's Bible have not been substantiated. Heinrich May in 1968 claimed to have found in England twelve leaves of a palimpsest containing parts of the Gospel of Matthew.[clarification needed][citation needed]

Only fragments of the Gothic translation of the Bible have been preserved. The translation was apparently done in the Balkans region by people in close contact with Greek Christian culture. The Gothic Bible was apparently used by the Visigoths in Occitania until the loss of Visigothic Occitania at the start of the 6th century,[13] in Visigothic Iberia until about 700, and perhaps for a time in Italy, the Balkans, and Ukraine until at least the mid-9th century. During the extermination of Arianism, Trinitarian Christians probably overwrote many texts in Gothic as palimpsests, or alternatively collected and burned Gothic documents. Apart from biblical texts, the only substantial Gothic document that still exists – and the only lengthy text known to have been composed originally in the Gothic language – is the Skeireins, a few pages of commentary on the Gospel of John.[citation needed]

Very few medieval secondary sources make reference to the Gothic language after about 800. In De incrementis ecclesiae Christianae (840–842), Walafrid Strabo, a Frankish monk who lived in Swabia, writes of a group of monks who reported that even then certain peoples in Scythia (Dobruja), especially around Tomis, spoke a sermo Theotiscus ('Germanic language'), the language of the Gothic translation of the Bible, and that they used such a liturgy.[14]

Many writers of the medieval texts that mention the Goths used the word Goths to mean any Germanic people in eastern Europe (such as the Varangians), many of whom certainly did not use the Gothic language as known from the Gothic Bible. Some writers even referred to Slavic-speaking people as "Goths". However, it is clear from Ulfilas's translation that – despite some puzzles – the Gothic language belongs with the Germanic language-group, not with Slavic.

Generally, the term "Gothic language" refers to the language of Ulfilas, but the attestations themselves date largely from the 6th century, long after Ulfilas had died.[citation needed]

Alphabet and transliteration

Summarize

Perspective

A few Gothic runic inscriptions were found across Europe, but due to early Christianization of the Goths, the Runic writing was quickly replaced by the newly invented Gothic alphabet.

Ulfilas's Gothic, as well as that of the Skeireins and various other manuscripts, was written using an alphabet that was most likely invented by Ulfilas himself for his translation. Some scholars (such as Braune) claim that it was derived from the Greek alphabet only while others maintain that there are some Gothic letters of Runic or Latin origin.

A standardized system is used for transliterating Gothic words into the Latin script. The system mirrors the conventions of the native alphabet, such as writing long /iː/ as ei. The Goths used their equivalents of e and o alone only for long higher vowels, using the digraphs ai and au (much as in French) for the corresponding short or lower vowels. There are two variant spelling systems: a "raw" one that directly transliterates the original Gothic script and a "normalized" one that adds diacritics (macrons and acute accents) to certain vowels to clarify the pronunciation or, in certain cases, to indicate the Proto-Germanic origin of the vowel in question. The latter system is usually used in the academic literature.

The following table shows the correspondence between spelling and sound for vowels:

| Gothic letter or digraph |

Roman equivalent |

"Normalised" transliteration |

Sound | Normal environment of occurrence (in native words) |

Paradigmatically alternating sound in other environments |

Proto-Germanic origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𐌰 | a | a | /a/ | Everywhere | — | /ɑ/ |

| ā | /aː/ | Before /h/, /hʷ/ | Does not occur | /ãː/ (before /h/) | ||

| 𐌰𐌹 | ai | aí | /ɛ/ | Before /h/, /hʷ/, /r/ | i /i/ | /e/, /i/ |

| ai | /ɛː/ | Before vowels | ē /eː/ | /ɛː/, /eː/ | ||

| ái | /ɛː/ | Not before vowels | aj /aj/ | /ɑi/ | ||

| 𐌰𐌿 | au | aú | /ɔ/ | Before /h/, /hʷ/, /r/ | u /u/ | /u/ |

| au | /ɔː/ | Before vowels | ō /oː/ | /ɔː/ | ||

| áu | /ɔː/ | Not before vowels | aw /aw/ | /ɑu/ | ||

| 𐌴 | e | ē | /eː/ | Not before vowels | ai /ɛː/ | /ɛː/, /eː/ |

| 𐌴𐌹 | ei | ei | /iː/ | Everywhere | — | /iː/; /ĩː/ (before /h/) |

| 𐌹 | i | i | /i/ | Everywhere except before /h/, /hʷ/, /r/ | aí /ɛ/ | /e/, /i/ |

| 𐌹𐌿 | iu | iu | /iu/ | Not before vowels | iw /iw/ | /eu/ (and its allophone [iu]) |

| 𐍉 | o | ō | /oː/ | Not before vowels | au /ɔː/ | /ɔː/ |

| 𐌿 | u | u | /u/ | Everywhere except before /h/, /hʷ/, /r/ | aú /ɔ/ | /u/ |

| ū | /uː/ | Everywhere | — | /uː/; /ũː/ (before /h/) |

Notes:

- This "normalised transliteration" system devised by Jacob Grimm is used in some modern editions of Gothic texts and in studies of Common Germanic. It signals distinctions not made by Ulfilas in his alphabet. Rather, they reflect various origins in Proto-Germanic. Thus,

- aí is used for the sound derived from the Proto-Germanic short vowels e and i before /h/ and /r/.

- ái is used for the sound derived from the Proto-Germanic diphthong ai. Some scholars have considered this sound to have remained as a diphthong in Gothic. However, Ulfilas was highly consistent in other spelling inventions, which makes it unlikely that he assigned two different sounds to the same digraph. Furthermore, he consistently used the digraph to represent Greek αι, which was then certainly a monophthong. A monophthongal value is accepted by Eduard Prokosch in his influential A Common Germanic Grammar.[15] It had earlier been accepted by Joseph Wright but only in an appendix to his Grammar of the Gothic Language.[16]

- ai is used for the sound derived from the Common Germanic long vowel ē before a vowel.

- áu is used for the sound derived from Common Germanic diphthong au. It cannot be related to a Greek digraph, since αυ then represented a sequence of a vowel and a spirant (fricative) consonant, which Ulfilas transcribed as aw in representing Greek words. Nevertheless, the argument based on simplicity is accepted by some influential scholars.[15][16]

- The "normal environment of occurrence" refers to native words. In foreign words, these environments are often greatly disturbed. For example, the short sounds /ɛ/ and /i/ alternate in native words in a nearly allophonic way, with /ɛ/ occurring in native words only before the consonants /h/, /hʷ/, /r/ while /i/ occurs everywhere else (nevertheless, there are a few exceptions such as /i/ before /r/ in hiri, /ɛ/ consistently in the reduplicating syllable of certain past-tense verbs regardless of the following consonant, which indicate that these sounds had become phonemicized). In foreign borrowings, however, /ɛ/ and /i/ occur freely in all environments, reflecting the corresponding vowel quality in the source language.

- Paradigmatic alterations can occur either intra-paradigm (between two different forms within a specific paradigm) or cross-paradigm (between the same form in two different paradigms of the same class). Examples of intra-paradigm alternation are gawi /ɡa.wi/ "district (nom.)" vs. gáujis /ɡɔː.jis/ "district (gen.)"; mawi /ma.wi/ "maiden (nom.)" vs. máujōs /mɔː.joːs/ "maiden (gen.)"; þiwi /θi.wi/ "maiden (nom.)" vs. þiujōs /θiu.joːs/ "maiden (gen.)"; taui /tɔː.i/ "deed (nom.)" vs. tōjis /toː.jis/ "deed (gen.)"; náus /nɔːs/ "corpse (nom.)" vs. naweis /na.wiːs/ "corpses (nom.)"; triu /triu/?? "tree (nom.)" vs. triwis /tri.wis/ "tree (gen.)"; táujan /tɔː.jan/ "to do" vs. tawida /ta.wi.ða/ "I/he did"; stōjan /stoː.jan/ "to judge" vs. stauida /stɔː.i.ða/ "I/he judged". Examples of cross-paradigm alternation are Class IV verbs qiman /kʷiman/ "to come" vs. baíran /bɛran/ "to carry, to bear", qumans /kʷumans/ "(having) come" vs. baúrans /bɔrans/ "(having) carried"; Class VIIb verbs lētan /leː.tan/ "to let" vs. saian /sɛː.an/ "to sow" (note similar preterites laílōt /lɛ.loːt/ "I/he let", saísō /sɛ.soː/ "I/he sowed"). A combination of intra- and cross-paradigm alternation occurs in Class V sniwan /sni.wan/ "to hasten" vs. snáu /snɔː/ "I/he hastened" (expected *snaw, compare qiman "to come", qam "I/he came").

- The carefully maintained alternations between iu and iw suggest that iu may have been something other than /iu/. Various possibilities have been suggested (for example, high central or high back unrounded vowels, such as [ɨ] [ʉ] [ɯ]); under these theories, the spelling of iu is derived from the fact that the sound alternates with iw before a vowel, based on the similar alternations au and aw. The most common theory, however, simply posits /iu/ as the pronunciation of iu.

- Macrons represent long ā and ū (however, long i appears as ei, following the representation used in the native alphabet). Macrons are often also used in the case of ē and ō; however, they are sometimes omitted since these vowels are always long. Long ā occurs only before the consonants /h/, /hʷ/ and represents Proto-Germanic nasalized /ãː(h)/ < earlier /aŋ(h)/; non-nasal /aː/ did not occur in Proto-Germanic. It is possible that the Gothic vowel still preserved the nasalization, or else that the nasalization was lost but the length distinction kept, as has happened with Lithuanian ą. Non-nasal /iː/ and /uː/ occurred in Proto-Germanic, however, and so long ei and ū occur in all contexts. Before /h/ and /hʷ/, long ei and ū could stem from either non-nasal or nasal long vowels in Proto-Germanic; it is possible that the nasalization was still preserved in Gothic but not written.

The following table shows the correspondence between spelling and sound for consonants:

| Gothic Letter | Roman | Sound (phoneme) | Sound (allophone) | Environment of occurrence | Paradigmatically alternating sound, in other environments | Proto-Germanic origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𐌱 | ⟨b⟩ | /b/ | [b] | Word-initially; after a consonant | – | /b/ |

| [β] | After a vowel, before a voiced sound | /ɸ/ (after a vowel, before an unvoiced sound) | ||||

| 𐌳 | ⟨d⟩ | /d/ | [d] | Word-initially; after a consonant | – | /d/ |

| [ð] | After a vowel, before a voiced sound | /θ/ (after a vowel, before an unvoiced sound) | ||||

| 𐍆 | ⟨f⟩ | /ɸ/ | [ɸ] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | /b/ [β] | /ɸ/; /b/ |

| 𐌲 | ⟨g⟩ | /ɡ/ | [ɡ] | Word-initially; after a consonant | – | /ɡ/ |

| [ɣ] | After a vowel, before a voiced sound | /ɡ/ [x] (after a vowel, not before a voiced sound) | ||||

| [x] | After a vowel, not before a voiced sound | /ɡ/ [ɣ] (after a vowel, before a voiced sound) | ||||

| /n/ | [ŋ] | Before k /k/, g /ɡ/ [ɡ], gw /ɡʷ/ (such usage influenced by Greek, compare gamma) | – | /n/ | ||

| ⟨gw⟩ | /ɡʷ/ | [ɡʷ] | After g /n/ [ŋ] | – | /ɡʷ/ | |

| 𐌷 | ⟨h⟩ | /h/ | [h] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | /ɡ/ [ɣ] | /x/ |

| 𐍈 | ⟨ƕ⟩ | /hʷ/ | [hʷ] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | – | /xʷ/ |

| 𐌾 | ⟨j⟩ | /j/ | [j] | Everywhere | – | /j/ |

| 𐌺 | ⟨k⟩ | /k/ | [k] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | – | /k/ |

| 𐌻 | ⟨l⟩ | /l/ | [l] | Everywhere | – | /l/ |

| 𐌼 | ⟨m⟩ | /m/ | [m] | Everywhere | – | /m/ |

| 𐌽 | ⟨n⟩ | /n/ | [n] | Everywhere | – | /n/ |

| 𐍀 | ⟨p⟩ | /p/ | [p] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | – | /p/ |

| 𐌵 | ⟨q⟩ | /kʷ/ | [kʷ] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | – | /kʷ/ |

| 𐍂 | ⟨r⟩ | /r/ | [r] | Everywhere | – | /r/ |

| 𐍃 | ⟨s⟩ | /s/ | [s] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | /z/ | /s/; /z/ |

| 𐍄 | ⟨t⟩ | /t/ | [t] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | – | /t/ |

| 𐌸 | ⟨þ⟩ | /θ/ | [θ] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | /d/ [ð] | /θ/; /d/ |

| 𐍅 | ⟨w⟩ | /w/ | [w] | Everywhere | – | /w/ |

| 𐌶 | ⟨z⟩ | /z/ | [z] | After a vowel, before a voiced sound | /s/ | /z/ |

- /hʷ/, which is written with a single character in the native alphabet, is transliterated using the symbol ⟨ƕ⟩, which is used only in transliterating Gothic.

- /kʷ/ is similarly written with a single character in the native alphabet and is transliterated q (with no following u).

- /ɡʷ/, however, is written with two letters in the native alphabet and hence 𐌲𐍅 (gw). The lack of a single letter to represent this sound may result from its restricted distribution (only after /n/) and its rarity.

- /θ/ is written þ, similarly to other Germanic languages.

- Although [ŋ] is the allophone of /n/ occurring before /ɡ/ and /k/, it is written g, following the native alphabet convention (which, in turn, follows Greek usage), which leads to occasional ambiguities, e.g. saggws [saŋɡʷs] "song" but triggws [triɡɡʷs] "faithful" (compare English "true").

Phonology

Summarize

Perspective

It is possible to determine more or less exactly how the Gothic of Ulfilas was pronounced, primarily through comparative phonetic reconstruction. Furthermore, because Ulfilas tried to follow the original Greek text as much as possible in his translation, it is known that he used the same writing conventions as those of contemporary Greek. Since the Greek of that period is well documented, it is possible to reconstruct much of Gothic pronunciation from translated texts. In addition, the way in which non-Greek names are transcribed in the Greek Bible and in Ulfilas's Bible is very informative.

Vowels

- /a/, /i/ and /u/ can be either long or short.[17] Gothic writing distinguishes between long and short vowels only for /i/ by writing i for the short form and ei for the long (a digraph or false diphthong), in an imitation of Greek usage (ει = /iː/). Single vowels are sometimes long where a historically present nasal consonant has been dropped in front of an /h/ (a case of compensatory lengthening). Thus, the preterite of the verb briggan [briŋɡan] "to bring" (English bring, Dutch brengen, German bringen) becomes brahta /braːhta/ (English brought, Dutch bracht, German brachte), from Proto-Germanic *branhtē. In detailed transliteration, when the intent is more phonetic transcription, length is noted by a macron (or failing that, often a circumflex): brāhta, brâhta. This is the only context in which /aː/ appears natively whereas /uː/, like /iː/, is found often enough in other contexts: brūks "useful" (Dutch gebruik, German Gebrauch, Icelandic brúk "use").

- /eː/ and /oː/ are long close-mid vowels. They are written as ⟨e⟩ and ⟨o⟩: neƕ [neːʍ] "near" (English nigh, Dutch nader, German nah); fodjan [foːdjan] "to feed".

- /ɛ/ and /ɔ/ are short open-mid vowels.[18] They are noted using the digraphs ai and au: taihun [tɛhun] "ten" (Dutch tien, German zehn, Icelandic tíu), dauhtar /dɔhtar/ "daughter" (Dutch dochter, German Tochter, Icelandic dóttir). In transliterating Gothic, accents are placed on the second vowel of these digraphs aí and aú to distinguish them from the original diphthongs ái and áu: taíhun, daúhtar. In most cases short [ɛ] and [ɔ] are allophones of /i, u/ before /r, h, ʍ/.[19] Furthermore, the reduplication syllable of the reduplicating preterites has ai as well, which was probably pronounced as a short [ɛ].[20] Finally, short [ɛ] and [ɔ] occur in loan words from Greek and Latin (aípiskaúpus [ɛpiskɔpus] = ἐπίσκοπος "bishop", laíktjo [lɛktjoː] = lectio "lection", Paúntius [pɔntius] = Pontius).

- The Germanic diphthongs /ai/ and /au/ appear as digraphs written ⟨ai⟩ and ⟨au⟩ in Gothic. Researchers have disagreed over whether they were still pronounced as diphthongs /ai̯/ and /au̯/ in Ulfilas's time (4th century) or had become long open-mid vowels: /ɛː/ and /ɔː/: ains [ains] / [ɛːns] "one" (German eins, Icelandic einn), augo [auɣoː] / [ɔːɣoː] "eye" (German Auge, Icelandic auga). It is most likely that the latter view is correct, as it is indisputable that the digraphs ⟨ai⟩ and ⟨au⟩ represent the sounds /ɛː/ and /ɔː/ in some circumstances (see below), and ⟨aj⟩ and ⟨aw⟩ were available to unambiguously represent the sounds /ai̯/ and /au̯/. The digraph ⟨aw⟩ is in fact used to represent /au/ in foreign words (such as Pawlus "Paul"), and alternations between ⟨ai⟩/⟨aj⟩ and ⟨au⟩/⟨aw⟩ are scrupulously maintained in paradigms where both variants occur (e.g. taujan "to do" vs. past tense tawida "did"). Evidence from transcriptions of Gothic names into Latin suggests that the sound change had occurred very recently when Gothic spelling was standardized: Gothic names with Germanic au are rendered with au in Latin until the 4th century and o later on (Austrogoti > Ostrogoti). The digraphs ⟨ai⟩ and ⟨au⟩ are normally written with an accent on the first vowel (ái, áu) when they correspond to Proto-Germanic /ai̯/ and /au̯/.

- Long [ɛː] and [ɔː] also occur as allophones of /eː/ and /uː, oː/ respectively before a following vowel: waian [wɛːan] "to blow" (Dutch waaien, German wehen), bauan [bɔːan] "to build" (Dutch bouwen, German bauen, Icelandic búa "to live, reside"), also in Greek words Trauada "Troad" (Gk. Τρῳάς). In detailed transcription these are notated ai, au.

- The existence of a vowel /y/ in Gothic is unclear. It is derived from the use of w to transcribe Greek υ (y) or the diphthong οι (oi), both of which were pronounced [y] in the Greek of the time. W is otherwise used to denote the consonant /w/). It may have been pronounced [i].[21]

- /iu/ is usually reconstructed as a falling diphthong ([iu̯]: diups [diu̯ps] "deep" (Dutch diep, German tief, Icelandic djúpur), though this has been disputed (see alphabet and transliteration section above).

- Greek diphthongs: In Ulfilas's era, all the diphthongs of Classical Greek had become simple vowels in speech (monophthongization), except for αυ (au) and ευ (eu), which were probably pronounced [aβ] and [ɛβ] (they evolved into [av~af] and [ev~ef] in Modern Greek.) Ulfilas notes them, in words borrowed from Greek, as aw and aiw, probably pronounced [au̯, ɛu̯]: Pawlus [pau̯lus] "Paul" (Gk. Παῦλος), aíwaggelista [ɛwaŋɡeːlista] "evangelist" (Gk. εὐαγγελιστής, via the Latin evangelista).

- All vowels (including diphthongs) can be followed by a [w], which was likely pronounced as the second element of a diphthong with roughly the sound of [u̯]. It seems likely that this is more of an instance of phonetic juxtaposition than of true diphthongs (such as, for example, the sound /aj/ in the French word paille ("straw"), which is not the diphthong /ai̯/ but rather a vowel followed by an approximant): alew [aleːw] "olive oil" ( < Latin oleum), snáiws [snɛːws] ("snow"), lasiws [lasiws] "tired" (English lazy).

Consonants

Gothic distinguished single or short consonants from long or geminated consonants: the latter were written double, as in atta [atːa] "dad", kunnan [kunːan] "to know" (Dutch kennen, German kennen "to know", Icelandic kunna). Gothic is rich in fricative consonants (although many of them may have been approximants; it is hard to separate the two) originating from Grimm's law and Verner's law. Gothic retained Proto-Germanic *z as /z/, unlike North Germanic languages and West Germanic languages, which turned this sound into /r/ through rhotacization. Voiced fricative consonants were devoiced at the ends of words.

Stops

- The voiceless stops /p/, /t/ and /k/ are regularly noted by p, t and k respectively: paska [paska] "Easter" (from the Greek πάσχα), tuggo [tuŋɡoː] "tongue", kalbo [kalboː] "calf".

- The letter q is probably a voiceless labiovelar stop, /kʷ/, comparable to the Latin qu: qiman [kʷiman] "to come". In later Germanic languages, this phoneme has become either a consonant cluster /kw/ of a voiceless velar stop + a labio-velar approximant (English qu) or a simple voiceless velar stop /k/ (English c, k)

- The voiced stops [b], [d] and [ɡ] are noted by the letters b, d and g. Like the other Germanic languages, they occurred in word-initial position, when doubled and after a nasal. In addition, they apparently occurred after other consonants,: arbi [arbi] "inheritance", huzd [huzd] "treasure". (This conclusion is based on their behavior at the end of a word, in which they do not change into voiceless fricatives, unlike when they occur after a vowel.)

- There was probably also a voiced labiovelar stop, [ɡʷ], which was written with the digraph gw. It occurred after a nasal, e.g. saggws [saŋɡʷs] "song", or long as a regular outcome of Germanic *ww: triggws [triɡʷːs] "faithful" (English true, German treu, Icelandic tryggur). The existence of a long [ɡʷː] separate from [ŋɡʷ], however, is not universally accepted.[22]

- Similarly, the letters ddj, which is the regular outcome of Germanic *jj, may represent a voiced palatal stop, [ɟː]:[citation needed] waddjus [waɟːus] "wall" (Icelandic veggur), twaddje [twaɟːeː] "two (genitive)" (Icelandic tveggja).[citation needed]

Fricatives

- /s/ and /z/ are usually written s and z. The latter corresponds to Germanic *z (which has become r or silent in the other Germanic languages); at the end of a word, it is regularly devoiced to s. E.g. saíhs [sɛhs] "six", máiza [mɛːza] "greater" (English more, Dutch meer, German mehr, Icelandic meira) versus máis [mɛːs] "more, rather".

- /ɸ/ and /θ/, written f and þ, are voiceless bilabial and voiceless dental fricatives respectively. It is likely that the relatively unstable sound /ɸ/ became /f/. The cluster /ɸl/ became /θl/ in some words but not others: þlauhs "flight" from Germanic *flugiz; þliuhan "flee" from Germanic *fleuhaną (but see flōdus "river", flahta "braid"). This sound change is unique among Germanic languages.[citation needed]

- [β], [ð] and [ɣ] are allophones of /b/, /d/ and /ɡ/ respectively, and are not distinguished from them in writing. [β] may have become [v], a more stable labiodental form. In the study of Germanic languages, these phonemes are usually transcribed as ƀ, đ and ǥ respectively: haban [haβan] "to have", þiuda [θiu̯ða] "people" (Dutch Diets, German Deutsch, Icelandic þjóð > English Dutch), áugo [ɔːɣoː] "eye" (English eye, Dutch oog, German Auge, Icelandic auga). The voiced fricative allophones were used when /b, d, ɡ/ came between vowels. When preceded by a vowel and followed by a voiceless consonant or by the end of a word, /b, d/ were devoiced to [ɸ, θ] and spelled as f, þ: e.g. hláifs [hlɛːɸs] "loaf" but genitive hláibis [hlɛːβis] "of a loaf", plural hláibōs [hlɛːβoːs] "loaves"; gif [ɡiɸ] "give (imperative)" (infinitive giban: German geben); miþ [miθ] "with" (Old English mid, Old Norse með, Dutch met, German mit). The velar consonant /ɡ/ was probably also phonetically devoiced in the same position, becoming the voiceless velar fricative [x], but this is less certain; it remained spelled as g and apparently did not merge with any other phoneme.

- /h/ (from Proto-Germanic *x) is written as h: haban "to have". It could occur in the coda of syllables (e.g. jah /jah/ "and" (Dutch, German, Scandinavian ja "yes") and unlike /ɸ/ and /θ/, it did not merge at the end of a word or before a voiceless consonant with its etymologically paired voiced consonant: /ɡ/ remained written as g, e.g. dags /dags/ "day" (German Tag). There are conflicting interpretations of what this data means in terms of phonetics. Some linguists interpret it as a sign that [ɣ] failed to be devoiced in this context, but given that the other voiced fricatives were subject to devoicing in this position, Howell 1991 argues it is more likely that /dags/ was pronounced with devoicing as [daxs] and coda /h/ was pronounced as something other than a voiceless velar fricative. Two phonetic values that have been proposed for syllable-final /h/ are uvular [χ] and glottal [h].[23]

- In some borrowed Greek words there is a special letter x, which represents the Greek letter χ (ch): Xristus [xristus] "Christ" (Gk. Χριστός).

- ƕ (also transcribed hw) is the labiovelar equivalent of /h/, derived from Proto-Indo-European *kʷ. It was probably pronounced [ʍ] (a voiceless [w]), as wh is pronounced in certain dialects of English and in Scots: ƕan /ʍan/ "when", ƕar /ʍar/ "where", ƕeits [ʍiːts] "white".

Sonorants

- Gothic has three nasal consonants, [m, n, ŋ]. The first two are phonemes, /m/ and /n/; the third, [ŋ], is an allophone found only in complementary distribution with the other two.

- The bilabial nasal /m/, transcribed m, can be found in any position in a syllable: e.g. guma 'man', bagms 'tree'.[24]

- The coronal nasal /n/, transcribed n, can be found in any position in a syllable. It assimilates to the place of articulation of a following stop consonant: before a bilabial consonant, it becomes [m] and before front of a velar stop, it becomes [ŋ]. Thus, clusters like [nb] or [nk] are not possible.

- The velar nasal [ŋ], transcribed g, is not a phoneme and cannot appear freely in Gothic. It occurs only before a velar stop as the result of nasal place assimilation, and so is in complementary distribution with /n/ and /m/. Following Greek conventions, it is normally written as g (sometimes n): þagkjan [θaŋkjan] "to think", sigqan [siŋkʷan] "to sink" ~ þankeiþ [θaŋkiːθ] "thinks". The cluster ggw sometimes denotes [ŋɡʷ], but sometimes [ɡʷː] (see above).

- /w/ is transliterated as w before a vowel: weis [wiːs] ("we"), twái [twai] "two" (German zwei).

- /j/ is written as j: jer [jeːr] "year", sakjo [sakjoː] "strife".

- /l/ and /r/ occur as in other European languages: laggs (possibly [laŋɡs], [laŋks] or [laŋɡz]) "long", mel [meːl] "hour" (English meal, Dutch maal, German Mahl, Icelandic mál). The exact pronunciation of /r/ is unknown, but it is usually assumed to be a trill [r] or a flap [ɾ]): raíhts /rɛhts/ "right", afar [afar] "after".

- /l/, /m/, /n/ and /r/ may occur either between two other consonants of lower sonority or word-finally after a consonant of lower sonority. It is probable that the sounds are pronounced partly or completely as syllabic consonants in such circumstances (as in English "bottle" or "bottom"): tagl [taɣl̩] or [taɣl] "hair" (English tail, Icelandic tagl), máiþms [mɛːθm̩s] or [mɛːθms] "gift", táikns [tɛːkn̩s] or [tɛːkns] "sign" (English token, Dutch teken, German Zeichen, Icelandic tákn) and tagr [taɣr̩] or [taɣr] "tear (as in crying)".

Accentuation and intonation

Accentuation in Gothic can be reconstructed through phonetic comparison, Grimm's law, and Verner's law. Gothic used a stress accent rather than the pitch accent of Proto-Indo-European. This is indicated by the shortening of long vowels [eː] and [oː] and the loss of short vowels [a] and [i] in unstressed final syllables.

Just as in other Germanic languages, the free moving Proto-Indo-European accent was replaced with one fixed on the first syllable of simple words. Accents do not shift when words are inflected. In most compound words, the location of the stress depends on the type of compound:

- In compounds in which the second word is a noun, the accent is on the first syllable of the first word of the compound.

- In compounds in which the second word is a verb, the accent falls on the first syllable of the verbal component. Elements prefixed to verbs are otherwise unstressed except in the context of separable words (words that can be broken in two parts and separated in regular usage such as separable verbs in German and Dutch). In those cases, the prefix is stressed.

For example, with comparable words from modern Germanic languages:

- Non-compound words: marka [ˈmarka] "border, borderlands" (English march, Dutch mark); aftra [ˈaɸtra] "after"; bidjan [ˈbiðjan] "pray" (Dutch, bidden, German bitten, Icelandic biðja, English bid).

- Compound words:

- Noun first element: guda-láus [ˈɡuðalɔːs] "godless".

- Verb second element: ga-láubjan [ɡaˈlɔːβjan] "believe" (Dutch geloven, German glauben < Old High German g(i)louben by syncope of the unaccented i).

Grammar

Summarize

Perspective

Morphology

Nouns and adjectives

Gothic preserves many archaic Indo-European features that are not always present in modern Germanic languages, in particular the rich Indo-European declension system. Gothic had nominative, accusative, genitive and dative cases, as well as vestiges of a vocative case that was sometimes identical to the nominative and sometimes to the accusative. The three genders of Indo-European were all present. Nouns and adjectives were inflected according to one of two grammatical numbers: the singular and the plural.

Nouns can be divided into numerous declensions according to the form of the stem: a, ō, i, u, an, ōn, ein, r, etc. Adjectives have two variants, indefinite and definite (sometimes indeterminate and determinate), with definite adjectives normally used in combination with the definite determiners (such as the definite article sa/þata/sō) while indefinite adjectives are used in other circumstances.,[25][26] Indefinite adjectives generally use a combination of a-stem and ō-stem endings, and definite adjectives use a combination of an-stem and ōn-stem endings. The concept of "strong" and "weak" declensions that is prevalent in the grammar of many other Germanic languages is less significant in Gothic because of its conservative nature: the so-called "weak" declensions (those ending in n) are, in fact, no weaker in Gothic (in terms of having fewer endings) than the "strong" declensions (those ending in a vowel), and the "strong" declensions do not form a coherent class that can be clearly distinguished from the "weak" declensions.

Although descriptive adjectives in Gothic (as well as superlatives ending in -ist and -ost) and the past participle may take both definite and indefinite forms, some adjectival words are restricted to one variant. Some pronouns take only definite forms: for example, sama (English "same"), adjectives like unƕeila ("constantly", from the root ƕeila, "time"; compare to the English "while"), comparative adjective and present participles. Others, such as áins ("some"), take only the indefinite forms.

The table below displays the declension of the Gothic adjective blind (English: "blind"), compared with the an-stem noun guma "man, human" and the a-stem noun dags "day":

| Number | Case | Definite/an-stem | Indefinite/a-stem | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noun | Adjective | Noun | Adjective | ||||||||

| root | masc. | neut. | fem. | root | masc. | neut. | fem. | ||||

| Singular | nom. | guma | blind- | -a | -o | dags | blind- | -s | — / -ata | -a | |

| acc. | guman | -an | -o | -on | dag | -ana | |||||

| dat. | gumin | -in | daga | -amma | -ái | ||||||

| gen. | gumins | -ins | -ons | dagis | -is | áizos | |||||

| Plural | nom. | gumans | -ans | -ona | dagos | -ái | -a | -os | |||

| acc. | dagans | -ans | |||||||||

| dat. | gumam | -am | -om | dagam | -áim | ||||||

| gen. | gumane | -ane | -ono | dage | -áize | -áizo | |||||

This table is, of course, not exhaustive. (There are secondary inflexions of various sorts not described here.) An exhaustive table of only the types of endings that Gothic took is presented below.

- vowel declensions:

- roots ending in -a, -ja, -wa (masculine and neuter): equivalent to the Greek and Latin second declension in ‑us / ‑ī and ‑ος / ‑ου;

- roots ending in -ō, -jō and -wō (feminine): equivalent to the Greek and Latin first declension in ‑a / ‑ae and ‑α / ‑ας (‑η / ‑ης);

- roots ending in -i (masculine and feminine): equivalent to the Greek and Latin third declension in ‑is / ‑is (abl. sg. ‑ī, gen. pl. -ium) and ‑ις / ‑εως;

- roots ending in -u (all three genders): equivalent to the Latin fourth declension in ‑us / ‑ūs and the Greek third declension in ‑υς / ‑εως;

- n-stem declensions, equivalent to the Greek and Latin third declension in ‑ō / ‑inis/ōnis and ‑ων / ‑ονος or ‑ην / ‑ενος:

- roots ending in -an, -jan, -wan (masculine);

- roots ending in -ōn and -ein (feminine);

- roots ending in -n (neuter): equivalent to the Greek and Latin third declension in ‑men / ‑minis and ‑μα / ‑ματος;

- minor declensions: roots ending in -r, -nd and vestigial endings in other consonants, equivalent to other third declensions in Greek and Latin.

Gothic adjectives follow noun declensions closely; they take same types of inflection.

Pronouns

Gothic inherited the full set of Indo-European pronouns: personal pronouns (including reflexive pronouns for each of the three grammatical persons), possessive pronouns, both simple and compound demonstratives, relative pronouns, interrogatives and indefinite pronouns. Each follows a particular pattern of inflection (partially mirroring the noun declension), much like other Indo-European languages. One particularly noteworthy characteristic is the preservation of the dual number, referring to two people or things; the plural was used only for quantities greater than two. Thus, "the two of us" and "we" for numbers greater than two were expressed as wit and weis respectively. While proto-Indo-European used the dual for all grammatical categories that took a number (as did Classical Greek and Sanskrit), most Old Germanic languages are unusual in that they preserved it only for pronouns. Gothic preserves an older system with dual marking on both pronouns and verbs (but not nouns or adjectives).

The simple demonstrative pronoun sa (neuter: þata, feminine: so, from the Indo-European root *so, *seh2, *tod; cognate to the Greek article ὁ, ἡ, τό and the Latin istud) can be used as an article, allowing constructions of the type definite article + weak adjective + noun.

The interrogative pronouns begin with ƕ-, which derives from the proto-Indo-European consonant *kʷ that was present at the beginning of all interrogatives in proto-Indo-European, cognate with the wh- at the beginning of many English interrogative, which, as in Gothic, are pronounced with [ʍ] in some dialects. The same etymology is present in the interrogatives of many other Indo-European languages: w- [v] in German, hv- in Danish, the Latin qu- (which persists in modern Romance languages), the Greek τ- or π-, the Slavic and Indic k- as well as many others.

Verbs

The bulk of Gothic verbs follow the type of Indo-European conjugation called 'thematic' because they insert a vowel derived from the reconstructed proto-Indo-European phonemes *e or *o between roots and inflexional suffixes. The pattern is also present in Greek and Latin:

- Latin – leg-i-mus ("we read"): root leg- + thematic vowel -i- (from *o) + suffix -mus.

- Greek – λύ-ο-μεν ("we untie"): root λυ- + thematic vowel -ο- + suffix -μεν.

- Gothic – nim-a-m ("we take"): root nim- + thematic vowel -a- (from *o) + suffix -m.

The other conjugation, called 'athematic', in which suffixes are added directly to roots, exists only in unproductive vestigial forms in Gothic, just like in Greek and Latin. The most important such instance is the verb "to be", which is athematic in Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, and many other Indo-European languages.

Gothic verbs are, like nouns and adjectives, divided into strong verbs and weak verbs. Weak verbs are characterised by preterites formed by appending the suffixes -da or -ta, parallel to past participles formed with -þ / -t. Strong verbs form preterites by ablaut (the alternating of vowels in their root forms) or by reduplication (prefixing the root with the first consonant in the root plus aí) but without adding a suffix in either case. This parallels the Greek and Sanskrit perfects. The dichotomy is still present in modern Germanic languages:

- weak verbs ("to have"):

- Gothic: haban, preterite: habáida, past participle: habáiþs;

- English: (to) have, preterite: had, past participle: had;

- German: haben, preterite: hatte, past participle: gehabt;

- Icelandic: hafa, preterite: hafði, past participle: haft;

- Dutch: hebben, preterite: had, past participle: gehad;

- Swedish: ha(va), preterite: hade, supine: haft;

- strong verbs ("to give"):

- Gothic: infinitive: giban, preterite: gaf;

- English: infinitive: (to) give, preterite: gave;

- German: infinitive: geben, preterite: gab;

- Icelandic: infinitive: gefa, preterite: gaf;

- Dutch: infinitive: geven, preterite: gaf;

- Swedish: infinitive: giva (ge), preterite: gav.

Verbal conjugation in Gothic have two grammatical voices: the active and the medial; three numbers: singular, dual (except in the third person) and plural; two tenses: present and preterite (derived from a former perfect); three grammatical moods: indicative, subjunctive (from an old optative form) and imperative as well as three kinds of nominal forms: a present infinitive, a present participle, and a past passive. Not all tenses and persons are represented in all moods and voices, as some conjugations use auxiliary forms.

Finally, there are forms called 'preterite-present': the old Indo-European perfect was reinterpreted as present tense. The Gothic word wáit, from the proto-Indo-European *woid-h2e ("to see" in the perfect), corresponds exactly to its Sanskrit cognate véda and in Greek to ϝοἶδα. Both etymologically should mean "I have seen" (in the perfect sense) but mean "I know" (in the preterite-present meaning). Latin follows the same rule with nōuī ("I have learned" and "I know"). The preterite-present verbs include áigan ("to possess") and kunnan ("to know") among others.

Syntax

Word order

The word order of Gothic is fairly free as is typical of other inflected languages. The natural word order of Gothic is assumed to have been like that of the other old Germanic languages; however, nearly all extant Gothic texts are translations of Greek originals and have been heavily influenced by Greek syntax.

Sometimes what can be expressed in one word in the original Greek will require a verb and a complement in the Gothic translation; for example, διωχθήσονται (diōchthēsontai, "they will be persecuted") is rendered:

wrakos winnand (2 Timothy 3:12) persecution-PL-ACC suffer-3PL "they will suffer persecution"

Likewise Gothic translations of Greek noun phrases may feature a verb and a complement. In both cases, the verb follows the complement, giving weight to the theory that basic word order in Gothic is object–verb. This aligns with what is known of other early Germanic languages.[27]

However, this pattern is reversed in imperatives and negations:[28]

waírþ hráins (Matthew 8:3, Mark 1:42, Luke 5:13) become-IMP clean "become clean!"

ni nimiþ arbi (Galatians 4:30) not take-3SG inheritance "he shall not become heir"

And in a wh-question the verb directly follows the question word:[28]

ƕa skuli þata barn waírþan (Luke 1:66) what shall-3SG-OPT the-NEUT child become-INF "What shall the child become?"

Clitics

Gothic has two clitic particles placed in the second position in a sentence, in accordance with Wackernagel's Law.

One such clitic particle is -u, indicating a yes–no question or an indirect question, like Latin -ne:

ni-u taíhun þái gahráinidái waúrþun? (Luke 17:17) not-Q ten that-MASC-PL cleanse-PP-MASC-PL become-3PL-PST "Were there not ten that were cleansed?" ei saíƕam qimái-u Helias nasjan ina (Matthew 27:49) that see-1PL come-3SG-OPT-Q Elias save-INF he-ACC "that we see whether or not Elias will come to save him"

The prepositional phrase without the clitic -u appears as af þus silbin: the clitic causes the reversion of originally voiced fricatives, unvoiced at the end of a word, to their voiced form; another such example is wileid-u "do you (pl.) want" from wileiþ "you (pl.) want". If the first word has a preverb attached, the clitic actually splits the preverb from the verb: ga-u-láubjats "do you both believe...?" from galáubjats "you both believe".

Another such clitic is -uh "and", appearing as -h after a vowel: ga-h-mēlida "and he wrote" from gamēlida "he wrote", urreis nim-uh "arise and take!" from the imperative form nim "take". After iþ or any indefinite besides sums "some" and anþar "another", -uh cannot be placed; in the latter category, this is only because indefinite determiner phrases cannot move to the front of a clause. Unlike, for example, Latin -que, -uh can only join two or more main clauses. In all other cases, the word jah "and" is used, which can also join main clauses.

More than one such clitics can occur in one word: diz-uh-þan-sat ijōs "and then he seized them (fem.)" from dissat "he seized" (notice again the voicing of diz-), ga-u-ƕa-sēƕi "whether he saw anything" from gasēƕi "he saw".[29]

Comparison to other Germanic languages

Summarize

Perspective

For the most part, Gothic is known to be significantly closer to Proto-Germanic than any other Germanic language[citation needed] except for that of the (scantily attested) Ancient Nordic runic inscriptions, which has made it invaluable in the reconstruction of Proto-Germanic[citation needed]. In fact, Gothic tends to serve as the primary foundation for reconstructing Proto-Germanic[citation needed]. The reconstructed Proto-Germanic conflicts with Gothic only when there is clearly identifiable evidence from other branches that the Gothic form is a secondary development.[citation needed]

Distinctive features

Gothic fails to display a number of innovations shared by all Germanic languages attested later:

- It lacks Germanic umlaut.

- It lacks rhotacism.

The language also preserved many features that were mostly lost in other early Germanic languages:

- dual inflections on verbs,

- morphological passive voice for verbs,

- reduplication in the past tense of Class VII strong verbs,

- clitic conjunctions that appear in second position of a sentence in accordance with Wackernagel's Law, splitting verbs from pre-verbs.

Lack of umlaut

Most conspicuously, Gothic shows no sign of morphological umlaut. Gothic fotus, pl. fotjus, can be contrasted with English foot : feet, German Fuß : Füße, Old Norse fótr : fœtr, Danish fod : fødder. These forms contain the characteristic change /u/ > /iː/ (English), /uː/ > /yː/ (German), /oː/ > /øː/ (ON and Danish) due to i-umlaut; the Gothic form shows no such change.

Lack of rhotacism

Proto-Germanic *z remains in Gothic as z or is devoiced to s. In North and West Germanic, *z changes to r by rhotacism:

- Gothic dius, gen. sg. diuzis ≠

- Old English dēor, gen. sg. dēores "wild animal" (Modern English deer).

Passive voice

Gothic retains a morphological passive voice inherited from Indo-European but unattested in all other Germanic languages except for the single fossilised form preserved in, for example, Old English hātte or Runic Norse (c. 400) haitē "am called", derived from Proto-Germanic *haitaną "to call, command".

The morphological passive in North Germanic languages (Swedish gör "does", görs "is being done") originates from the Old Norse middle voice, which is an innovation not inherited from Indo-European.

Dual number

Unlike other Germanic languages, which retained dual numbering only in some pronoun forms, Gothic has dual forms both in pronouns and in verbs. Dual verb forms exist only in the first and second person and only in the active voice; in all other cases, the corresponding plural forms are used. In pronouns, Gothic has first and second person dual pronouns: Gothic and Old English wit, Old Norse vit "we two" (thought to have been in fact derived from *wi-du literally "we two").

Reduplication

Gothic possesses a number of verbs which form their preterite by reduplication, another archaic feature inherited from Indo-European. While traces of this category survived elsewhere in Germanic, the phenomenon is largely obscured in these other languages by later sound changes and analogy. In the following examples the infinitive is compared to the third person singular preterite indicative:

- Gothic saian "to sow" : saiso

- Old Norse sá : seri < Proto-Germanic *sezō

- Gothic laikan "to play" : lailaik

- Old English lācan : leolc, lēc

Classification

The standard theory of the origin of the Germanic languages divides the languages into three groups: East Germanic (Gothic and a few other very scantily-attested languages), North Germanic (Old Norse and its derivatives, such as Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Icelandic, and Faroese) and West Germanic (all others, including Old English, Old High German, Old Saxon, Old Dutch, Old Frisian and the numerous modern languages derived from these, including English, German, and Dutch). Sometimes, a further grouping, that of the Northwest Germanic languages, is posited as containing the North Germanic and West Germanic languages, reflecting the hypothesis that Gothic was the first attested language to branch off.

A minority opinion (the so-called Gotho-Nordic hypothesis) instead groups North Germanic and East Germanic together. It is based partly on historical claims: for example, Jordanes, writing in the 6th century, ascribes to the Goths a Scandinavian origin. There are a few linguistically significant areas in which Gothic and Old Norse agree against the West Germanic languages.

Perhaps the most obvious is the evolution of the Proto-Germanic *-jj- and *-ww- into Gothic ddj (from Pre-Gothic ggj?) and ggw, and Old Norse ggj and ggv ("Holtzmann's Law"), in contrast to West Germanic where they remained as semivowels. Compare Modern English true, German treu, with Gothic triggws, Old Norse tryggr.

However, it has been suggested that these are, in fact, two separate and unrelated changes.[30] A number of other posited similarities exist (for example, the existence of numerous inchoative verbs ending in -na, such as Gothic ga-waknan, Old Norse vakna; and the absence of gemination before j, or (in the case of old Norse) only g geminated before j, e.g. Proto-Germanic *kunją > Gothic kuni (kin), Old Norse kyn, but Old English cynn, Old High German kunni). However, for the most part these represent shared retentions, which are not valid means of grouping languages. That is, if a parent language splits into three daughters A, B and C, and C innovates in a particular area but A and B do not change, A and B will appear to agree against C. That shared retention in A and B is not necessarily indicative of any special relationship between the two.

Similar claims of similarities between Old Gutnish (Gutniska) and Old Icelandic are also based on shared retentions rather than shared innovations.

Another commonly-given example involves Gothic and Old Norse verbs with the ending -t in the 2nd person singular preterite indicative, and the West Germanic languages have -i. The ending -t can regularly descend from the Proto-Indo-European perfect ending *-th₂e, while the origin of the West Germanic ending -i (which, unlike the -t-ending, unexpectedly combines with the zero-grade of the root as in the plural) is unclear, suggesting that it is an innovation of some kind, possibly an import from the optative. Another possibility is that this is an example of independent choices made from a doublet existing in the proto-language. That is, Proto-Germanic may have allowed either -t or -i to be used as the ending, either in free variation or perhaps depending on dialects within Proto-Germanic or the particular verb in question. Each of the three daughters independently standardized on one of the two endings and, by chance, Gothic and Old Norse ended up with the same ending.

Other isoglosses have led scholars to propose an early split between East and Northwest Germanic. Furthermore, features shared by any two branches of Germanic do not necessarily require the postulation of a proto-language excluding the third, as the early Germanic languages were all part of a dialect continuum in the early stages of their development, and contact between the three branches of Germanic was extensive.

Polish linguist Witold Mańczak argued that Gothic is closer to German (specifically Upper German) than to Scandinavian and suggested that their ancestral homeland was located in the southernmost part of the Germanic territories, close to present-day Austria, rather than in Scandinavia. Frederik Kortlandt has agreed with Mańczak's hypothesis, stating: "I think that his argument is correct and that it is time to abandon Iordanes' classic view that the Goths came from Scandinavia."[31]

Influence

The reconstructed Proto-Slavic language features several apparent borrowed words from East Germanic (presumably Gothic), such as *xlěbъ, "bread", vs. Gothic hlaifs.[32]

The Romance languages also preserve several loanwords from Gothic, such as Portuguese agasalho (warm clothing), from Gothic *𐌲𐌰𐍃𐌰𐌻𐌾𐌰 (*gasalja, "companion, comrade"); ganso (goose), from Gothic *𐌲𐌰𐌽𐍃 (*gans, "goose"); luva (glove), from Gothic 𐌻𐍉𐍆𐌰 (lōfa, "palm of the hand"); and trégua (truce), from Gothic 𐍄𐍂𐌹𐌲𐌲𐍅𐌰 (triggwa, "treaty; covenant"). Other examples include the French broder (to embroider), from Gothic *𐌱𐍂𐌿𐌶𐌳𐍉𐌽 (*bruzdon, "to embroider"); gaffe (gaffe), from Gothic 𐌲𐌰𐍆𐌰𐌷 (gafāh, "catch; something which is caught"); and the Italian bega (quarrel, dispute), from Gothic *𐌱𐌴𐌲𐌰 (*bēga, "quarrel").

Use in Romanticism and the Modern Age

Summarize

Perspective

J. R. R. Tolkien

Several linguists have made use of Gothic as a creative language. The most famous example is "Bagme Bloma" ("Flower of the Trees") by J. R. R. Tolkien, part of Songs for the Philologists. It was published privately in 1936 for Tolkien and his colleague E. V. Gordon.[33]

Tolkien's use of Gothic is also known from a letter from 1965 to Zillah Sherring. When Sherring bought a copy of Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War in Salisbury, she found strange inscriptions in it; after she found his name in it, she wrote him a letter and asked him if the inscriptions were his, including the longest one on the back, which was in Gothic. In his reply to her he corrected some of the mistakes in the text; he wrote for example that hundai should be hunda and þizo boko ("of those books"), which he suggested should be þizos bokos ("of this book"). A semantic inaccuracy of the text which he mentioned himself is the use of lisan for read, while this was ussiggwan. Tolkien also made a calque of his own name in Gothic in the letter, which according to him should be Ruginwaldus Dwalakoneis.[34]

Gothic is also known to have served as the primary inspiration for Tolkien's invented language, Taliska[35] which, in his legendarium, was the language spoken by the race of Men during the First Age before being displaced by another of his invented languages, Adûnaic. As of 2022[update], Tolkien's Taliska grammar has not been published.

Others

On 10 February 1841, the Bayerische Akademie für Wissenschaften published a reconstruction in Gothic of the Creed of Ulfilas.[36]

The Thorvaldsen museum also has an alliterative poem, "Thunravalds Sunau", from 1841 by Massmann, the first publisher of the Skeireins, written in the Gothic language. It was read at a great feast dedicated to Thorvaldsen in the Gesellschaft der Zwanglosen in Munich on July 15, 1841. This event is mentioned by Ludwig von Schorn in the magazine Kunstblatt from the 19th of July, 1841.[37] Massmann also translated the academic commercium song Gaudeamus into Gothic in 1837.[38]

In 2012, professor Bjarne Simmelkjær Hansen of the University of Copenhagen published a translation into Gothic of Adeste Fideles for Roots of Europe.[39]

In Fleurs du Mal, an online magazine for art and literature, the poem Overvloed of Dutch poet Bert Bevers appeared in a Gothic translation.[40][full citation needed]

Alice in Wonderland has been translated into Gothic (Balþos Gadedeis Aþalhaidais in Sildaleikalanda) by David Carlton in 2015 and is published by Michael Everson.[41][full citation needed][42][full citation needed]

Examples

Summarize

Perspective

The Lord's Prayer in Gothic:

𐌰𐍄𐍄𐌰

atta

/ˈatːa

Father

𐌿𐌽𐍃𐌰𐍂

unsar

ˈunsar

our,

𐌸𐌿

þu

θuː

thou

𐌹𐌽

in

in

in

𐌷𐌹𐌼𐌹𐌽𐌰𐌼

himinam

ˈhiminam

heaven,

𐍅𐌴𐌹𐌷𐌽𐌰𐌹

weihnai

ˈwiːhnɛː

be holy

𐌽𐌰𐌼𐍉

namo

ˈnamoː

name

𐌸𐌴𐌹𐌽

þein

θiːn

thy.

𐌵𐌹𐌼𐌰𐌹

qimai

ˈkʷimɛː

Come

𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌹𐌽𐌰𐍃𐍃𐌿𐍃

þiudinassus

ˈθiu̯ðinasːus

kingdom

𐌸𐌴𐌹𐌽𐍃

þeins

θiːns

thy,

𐍅𐌰𐌹𐍂𐌸𐌰𐌹

wairþai

ˈwɛrθɛː

happen

𐍅𐌹𐌻𐌾𐌰

wilja

ˈwilja

will

𐌸𐌴𐌹𐌽𐍃

þeins

θiːns

thy,

𐍃𐍅𐌴

swe

sweː

as

𐌹𐌽

in

in

in

𐌷𐌹𐌼𐌹𐌽𐌰

himina

ˈhimina

heaven

𐌾𐌰𐌷

jah

jah

also

𐌰𐌽𐌰

ana

ana

on

𐌰𐌹𐍂𐌸𐌰𐌹

airþai

ˈɛrθɛː

earth.

𐌷𐌻𐌰𐌹𐍆

hlaif

hlɛːɸ

Loaf

𐌿𐌽𐍃𐌰𐍂𐌰𐌽𐌰

unsarana

ˈunsarana

our,

𐌸𐌰𐌽𐌰

þana

ˈθana

the

𐍃𐌹𐌽𐍄𐌴𐌹𐌽𐌰𐌽

sinteinan

ˈsinˌtiːnan

daily,

𐌲𐌹𐍆

gif

ɡiɸ

give

𐌿𐌽𐍃

uns

uns

us

𐌷𐌹𐌼𐌼𐌰

himma

ˈhimːa

this

𐌳𐌰𐌲𐌰

daga

ˈdaɣa

day,

𐌾𐌰𐌷

jah

jah

and

𐌰𐍆𐌻𐌴𐍄

aflet

aɸˈleːt

forgive

𐌿𐌽𐍃

uns

uns

us,

𐌸𐌰𐍄𐌴𐌹

þatei

ˈθatiː

that

𐍃𐌺𐌿𐌻𐌰𐌽𐍃

skulans

ˈskulans

debtors

𐍃𐌹𐌾𐌰𐌹𐌼𐌰

sijaima

ˈsijɛːma

be,

𐍃𐍅𐌰𐍃𐍅𐌴

swaswe

ˈswasweː

just as

𐌾𐌰𐌷

jah

jah

also

𐍅𐌴𐌹𐍃

weis

ˈwiːs

we

𐌰𐍆𐌻𐌴𐍄𐌰𐌼

afletam

aɸˈleːtam

forgive

𐌸𐌰𐌹𐌼

þaim

θɛːm

those

𐍃𐌺𐌿𐌻𐌰𐌼

skulam

ˈskulam

debtors

𐌿𐌽𐍃𐌰𐍂𐌰𐌹𐌼

unsaraim

ˈunsarɛːm

our.

𐌾𐌰𐌷

jah

jah

And

𐌽𐌹

ni

ni

not

𐌱𐍂𐌹𐌲𐌲𐌰𐌹𐍃

briggais

ˈbriŋɡɛːs

bring

𐌿𐌽𐍃

uns

uns

us

𐌹𐌽

in

in

in

𐍆𐍂𐌰𐌹𐍃𐍄𐌿𐌱𐌽𐌾𐌰𐌹

fraistubnjai

ˈɸrɛːstuβnijɛː

temptation,

𐌰𐌺

ak

ak

but

𐌻𐌰𐌿𐍃𐌴𐌹

lausei

ˈlɔːsiː

loose

𐌿𐌽𐍃

uns

uns

us

𐌰𐍆

af

aɸ

from

𐌸𐌰𐌼𐌼𐌰

þamma

ˈθamːa

the

𐌿𐌱𐌹𐌻𐌹𐌽

ubilin

ˈuβilin

evil.

𐌿𐌽𐍄𐌴

unte

ˈunteː

For

𐌸𐌴𐌹𐌽𐌰

þeina

ˈθiːna

thine

𐌹𐍃𐍄

ist

ist

is

𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰𐌽𐌲𐌰𐍂𐌳𐌹

þiudangardi

ˈθiu̯ðanˌɡardi

kingdom

𐌾𐌰𐌷

jah

jah

and

𐌼𐌰𐌷𐍄𐍃

mahts

mahts

might

𐌾𐌰𐌷

jah

jah

and

𐍅𐌿𐌻𐌸𐌿𐍃

wulþus

ˈwulθus

glory

𐌹𐌽

in

in

in

𐌰𐌹𐍅𐌹𐌽𐍃

aiwins

ˈɛːwins/

eternity.

See also

General references

- G. H. Balg: A Gothic grammar with selections for reading and a glossary. New York: Westermann & Company, 1883 (archive.org).

- G. H. Balg: A comparative glossary of the Gothic language with especial reference to English and German. New York: Westermann & Company, 1889 (archive.org).

- Bennett, William Holmes (1980). An Introduction to the Gothic Language. New York: Modern Language Association of America.

- W. Braune and E. Ebbinghaus, Gotische Grammatik, 17th edition 1966, Tübingen

- 20th edition, 2004. ISBN 3-484-10852-5 (hbk), ISBN 3-484-10850-9 (pbk)

- Fausto Cercignani, "The Development of the Gothic Short/Lax Subsystem", in Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung, 93/2, 1979, pp. 272–278.

- Fausto Cercignani, "The Reduplicating Syllable and Internal Open Juncture in Gothic", in Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung, 93/1, 1979, pp. 126–132.

- Fausto Cercignani, "The Enfants Terribles of Gothic 'Breaking': hiri, aiþþau, etc.", in The Journal of Indo-European Studies, 12/3–4, 1984, pp. 315–344.

- Fausto Cercignani, "The Development of the Gothic Vocalic System", in Germanic Dialects: Linguistic and Philological Investigations, edited by Bela Brogyanyi and Thomas Krömmelbein, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, Benjamins, 1986, pp. 121–151.

- N. Everett, "Literacy from Late Antiquity to the early Middle Ages, c. 300–800 AD", The Cambridge Handbook of Literacy, ed. D. Olson and N. Torrance (Cambridge, 2009), pp. 362–385.

- Carla Falluomini, "Traces of Wulfila's Bible Translation in Visigothic Gaul", Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik 80 (2020) pp. 5–24.

- Kortlandt, Frederik (2001). "The origin of the Goths" (PDF). Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik. 55: 21–25. doi:10.1163/18756719-055-01-90000004.

- W. Krause, Handbuch des Gotischen, 3rd edition, 1968, Munich.

- Thomas O. Lambdin, An Introduction to the Gothic Language, Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2006, Eugene, Oregon.

- Miller, D. Gary (2019). The Oxford Gothic Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198813590.

- F. Mossé, Manuel de la langue gotique, Aubier Éditions Montaigne, 1942

- E Prokosch, A Comparative Germanic Grammar, 1939, The Linguistic Society of America for Yale University.

- Irmengard Rauch, Gothic Language: Grammar, Genetic Provenance and Typology, Readings, Peter Lang Publishing Inc; 2nd Revised edition, 2011

- C. Rowe, "The problematic Holtzmann’s Law in Germanic", Indogermanische Forschungen, Bd. 108, 2003. 258–266.

- Skeat, Walter William (1868). A Moeso-Gothic glossary. London: Asher & Co.

- Stearns, MacDonald (1978). Crimean Gothic. Analysis and Etymology of the Corpus. Saratoga, California: Anma Libri. ISBN 0-915838-45-1.

- Wilhelm Streitberg, Die gotische Bibel , 4th edition, 1965, Heidelberg

- Joseph Wright, Grammar of the Gothic language, 2nd edition, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1966

- 2nd edition, 1981 reprint by Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-811185-1

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.