Gandhara

Ancient Indo-Aryan civilization of Sapta Sindhu From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Gandhara (IAST: Gandhāra) was an ancient Indo-Aryan[1] region in present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan.[2][3][4] The core of the region of Gandhara was the Peshawar (Pushkalawati) and Swat valleys extending as far east as the Pothohar Plateau in Punjab, though the cultural influence of Greater Gandhara extended westwards into the Kabul valley in Afghanistan, and northwards up to the Karakoram range.[5][6] The region was a central location for the spread of Buddhism to Central Asia and East Asia with many Chinese Buddhist pilgrims visiting the region.[7]

| Gandhāra Gandhara | |

|---|---|

| c. 1200 BCE–1001 CE | |

Location of Gandhara in South Asia (Afghanistan and Pakistan) | |

Approximate geographical region of Gandhara centered on the Peshawar Basin, in present-day northwest Pakistan | |

| Capital | Puṣkalavati Puruṣapura Takshashila Udabhandapura |

| Government | |

| Raja | |

• c. 6th/5th cent. BCE | Pushkarasarin |

• c. 330 BCE | Taxiles |

• c. 321 BCE | Chandragupta Maurya |

• c. 46 CE | Sases |

• c. 127 CE | Kanishka |

• c. 514 CE | Mihirakula |

• 964 – 1001 | Jayapala |

| Historical era | Antiquity |

• Established | c. 1200 BCE |

| 27 November 1001 CE | |

| Today part of | Pakistan Afghanistan |

Between the third century BCE and third century CE, Gāndhārī, a Middle Indo-Aryan language written in the Kharosthi script, acted as the lingua franca of the region and through Buddhism, the language spread as far as China based on Gandhāran Buddhist texts.[8] Famed for its unique Gandharan style of art, the region attained its height from the 1st century to the 5th century CE under the Kushan Empire which had their capital at Puruṣapura, ushering the period known as Pax Kushana.[9]

The history of Gandhara originates with the Gandhara grave culture, characterized by a distinctive burial practice. During the Vedic period Gandhara gained recognition as one of the sixteen Mahajanapadas, or 'great realms', within South Asia playing a role in the Kurukshetra War. In the 6th or 5th century BCE, King Pukkusāti governed the region either before or after Gandhara succumbed to conquest by the Achaemenid Empire of Persia.[10][11] During the Wars of Alexander the Great, the region was split into two factions with Taxiles, the king of Taxila, allying with Alexander the Great,[12] while the Western Gandharan tribes, exemplified by the Aśvaka around the Swat valley, resisted.[13]

Following the Macedonian downfall, Gandhara became part of the Mauryan Empire with Chandragupta Maurya receiving an education in Taxila under Chanakya and later assumed control with his support.[14][15] Subsequently, Gandhara was successively annexed by the Indo-Greeks, Indo-Scythians, and Indo-Parthians though a regional Gandharan kingdom, known as the Apracharajas, retained governance during this period until the ascent of the Kushan Empire. The zenith of Gandhara's cultural and political influence transpired during Kushan rule, before succumbing to devastation during the Hunnic Invasions.[16] However, the region experienced a resurgence under the Turk Shahis and Hindu Shahis.

Etymology

Summarize

Perspective

Gandhara was known in Sanskrit as Gandhāraḥ (गन्धारः) and in Avestan as 'Vaēkərəta. In Old Persian, Gandhara was known as Gadāra (𐎥𐎭𐎠𐎼, also transliterated as Gandāra since the nasal "n" before consonants were omitted in Old Persian).[17] In Chinese, Gandhara is known as Jiāntuóluó (traditional Chinese: 犍陀羅; simplified Chinese: 犍陀罗, also written 健馱邏; 健驮逻), with the Middle Chinese pronunciation reconstructed as kɨɐndala. One state of the region named Jìbīn (罽賓; 罽宾, also romanized as Kipin) is recorded in the Book of Han.

One proposed origin of the name is from the Sanskrit word gandhaḥ (गन्धः), meaning "perfume" and "referring to the spices and aromatic herbs which they (the inhabitants) traded and with which they anointed themselves".[18][19] The Gandhari people are a tribe mentioned in the Rigveda, the Atharvaveda, and later Vedic texts.[20] This origin is also supported by the word Gandhara meaning “fragrance bringer” in the Pashayi language. A Persian form of the name, Gandara, mentioned in the Behistun inscription of Emperor Darius I,[21][22] was translated as Paruparaesanna (Para-upari-sena, meaning "beyond the Hindu Kush") in Babylonian and Elamite in the same inscription.[23] In Greek, Gandhara was known as Paropamisadae.[24]

Geography

Summarize

Perspective

The geographical location of Gandhara has undergone much alteration throughout history, with the general understanding being the region situating between Pothohar in contemporary Punjab, the Swat valley, and the Khyber Pass also extending along the Kabul River.[25] The prominent urban centres within this geographical scope were Taxila and Pushkalavati.[26] According to a specific Jataka, Gandhara's territorial extent at a certain period encompassed the region of Kashmir.[27] The Eastern border of Gandhara has been proposed to be the Jhelum River based on arachaeological Gandharan art discoveries however further evidence is needed to support this,[28][29] though during the rule of Alexander the Great the kingdom of Taxila stretched to the Hydaspes (Jhelum river).[30]

The term Greater Gandhara describes the cultural and linguistic extent of Gandhara and its language, Gandhari.[31] In later historical contexts, Greater Gandhara encompassed the territories of Jibin and Oddiyana which had splintered from Gandhara proper and also extended into parts of Bactria and the Tarim Basin. Oddiyana was situated in the vicinity of the Swat valley, while Jibin corresponded to the region of Kapisa, south of the Hindu Kush. However during the 5th and 6th centuries CE, Jibin was often considered synonymous with Gandhara.[32]

The Udichya region was another region mentioned in ancient texts and is noted by Pāṇini as comprising both the regions of Vahika and Gandhara.[33]

History

Summarize

Perspective

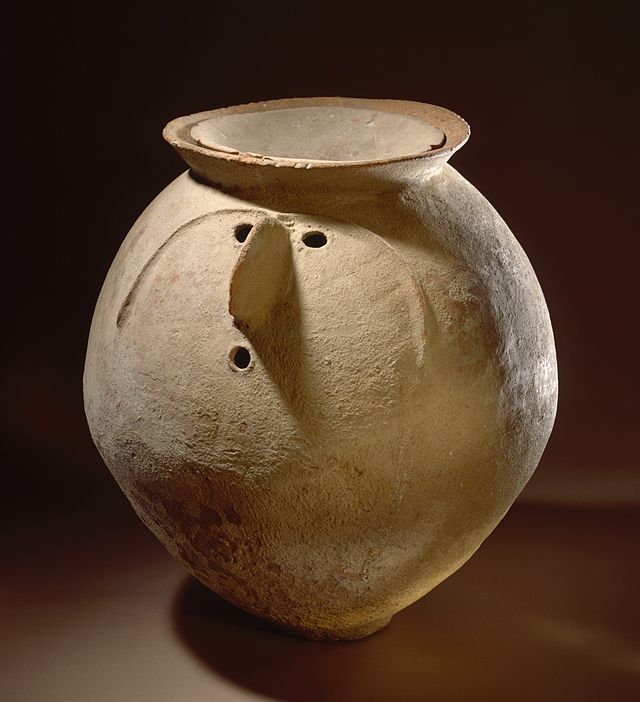

Gandhāra grave culture

Gandhara's first recorded culture was the Grave Culture that emerged c. 1200 BCE and lasted until 800 BCE,[34] and named for their distinct funerary practices. It was found along the Middle Swat River course, even though earlier research considered it to be expanded to the Valleys of Dir, Kunar, Chitral, and Peshawar.[35] It has been regarded as a token of the Indo-Aryan migrations but has also been explained by local cultural continuity. Backwards projections, based on ancient DNA analyses, suggest ancestors of Swat culture people mixed with a population coming from Inner Asia Mountain Corridor, which carried Steppe ancestry, sometime between 1900 and 1500 BCE.[36]

Vedic Gandhāra

According to Rigvedic tradition, Yayati was the progenitor of the prominent Udichya (Gandhara and Vahika tribes) and had numerous sons, including Anu, Puru, and Druhyu. The lineage of Anu gave rise to the Madra, Kekaya, Sivi and Uśīnara kingdoms, while the Druhyu tribe has been associated with the Gandhara kingdom.[37]

The first mention of the Gandhārīs is attested once in the Ṛigveda as a tribe that has sheep with good wool. In the Atharvaveda, the Gandhārīs are mentioned alongside the Mūjavants, the Āṅgeyas and the Māgadhīs in a hymn asking fever to leave the body of the sick man and instead go those aforementioned tribes. The tribes listed were the furthermost border tribes known to those in Madhyadeśa, the Āṅgeyas and Māgadhīs in the east, and the Mūjavants and Gandhārīs in the north.[38][39] The Gandhara tribe, after which it is named, is attested in the Rigveda (c. 1500 – c. 1200 BCE),[40][41] while the region is mentioned in the Zoroastrian Avesta as Vaēkərəta, the seventh most beautiful place on earth created by Ahura Mazda.

The Gāndhārī king Nagnajit and his son Svarajit are mentioned in the Brāhmaṇas, according to which they received Brahmanic consecration, but their family's attitude towards ritual is mentioned negatively,[42] with the royal family of Gandhāra during this period following non-Brahmanical religious traditions. According to the Jain Uttarādhyayana-sūtra, Nagnajit, or Naggaji, was a prominent king who had adopted Jainism and was comparable to Dvimukha of Pāñcāla, Nimi of Videha, Karakaṇḍu of Kaliṅga, and Bhīma of Vidarbha; Buddhist sources instead claim that he had achieved paccekabuddhayāna.[43][44][45]

By the later Vedic period, the situation had changed, and the Gāndhārī capital of Takṣaśila had become an important centre of knowledge where the men of Madhya-desa went to learn the three Vedas and the eighteen branches of knowledge, with the Kauśītaki Brāhmaṇa recording that brāhmaṇas went north to study. According to the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa and the Uddālaka Jātaka, the famous Vedic philosopher Uddālaka Āruṇi was among the famous students of Takṣaśila, and the Setaketu Jātaka claims that his son Śvetaketu also studied there. In the Chāndogya Upaniṣad, Uddālaka Āruṇi himself favourably referred to Gāndhārī education to the Vaideha king Janaka.[42] During the 6th century BCE, Gandhāra was an important imperial power in north-west Iron Age South Asia, with the valley of Kaśmīra being part of the kingdom.[43] Due to this important position, Buddhist texts listed the Gandhāra kingdom as one of the sixteen Mahājanapadas ("great realms") of Iron Age South Asia. It was the home of Gandhari, the princess and her brother Shakuni the king of Gandhara Kingdom.[46][47]

Pukkusāti and Achaemenid Gandhāra

During the 6th or 5th century BCE, Gandhara was governed under the reign of King Pukkusāti. There are no historical facts known for certain about Pukkusāti, and all theories about his reign are speculative relying on later Buddhist sources.[48][49] It is debated whether he ruled before or after the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley, and is unknown what kind of relationship he historically had with the Persian Achaemenid rulers.[11] According to Buddhist accounts written centuries later,[49] he had forged diplomatic ties with Magadha and achieved victories over neighbouring kingdoms such as that of the realm of Avanti.[50] Pukkusāti's kingdom was described as being 100 Yojanas in width, approximately 500 to 800 miles wide, with his capital at Taxila in modern day Punjab as stated in early Jatakas.[51]

It is noted by R. C. Majumdar that Pukkusāti would have been contemporary to the Achamenid king Cyrus the Great[52] and according to the scholar Buddha Prakash, Pukkusāti might have acted as a bulwark against the expansion of the Persian Achaemenid Empire into Gandhara. This hypothesis posits that the army which Nearchus claimed Cyrus had lost in Gedrosia had been defeated by Pukkusāti's Gāndhārī kingdom.[44] Therefore, following Prakash's position, the Achaemenids would have been able to conquer Gandhāra only after a period of decline after the reign of Pukkusāti, combined with the growth of Achaemenid power under the kings Cambyses II and Darius I.[44] However, the presence of Gandhāra among the list of Achaemenid provinces in Darius's Behistun Inscription confirms that his empire had inherited this region from Cyrus.[10] Assuming that Pukkusāti lived during the 6th century BCE, is unknown whether he remained in power after the Achaemenid conquest as a Persian vassal or if he was replaced by a Persian satrap, although Buddhist sources claim that he renounced his throne and became a monk after becoming a disciple of the Buddha.[53] The annexation under Cyrus was limited to the Western sphere of Gandhāra as only during the reign of Darius the Great did the region between the Indus River and the Jhelum River become annexed.[44]

However, with alternative chronologies which date the Buddha's lifetime (and his contemporary kings) as much as a century later, it is alternatively possible that Pukkusāti in fact lived as much as a century after the Achaemenid conquest. Among scholars who favour the latter chronology, it remains an open question for debate, what kind of relationship Pukkusāti historically had with the Persian Achaemenid rulers. Possible theories are: he "may belong to a period when the Achaemenids had already lost their hold over Indian provinces," or he may have been holding power in eastern parts of Gandhara such as Taxila (speculatively considered by some scholars to be outside the Achaemenid dominions), or may have been serving as a vassal of the Achaemenids but with autonomy to conduct warfare and diplomacy with independent Indian states, similar to the "active and often independent role the western satraps had in Greek politics". Thus it is considered that he may have been an important intermediary for cultural influence between Ancient Persia and India.[54]

Megasthenes Indica, states that the Achaemenids never conquered India and had only approached its borders after battling with the Massagetae, it further states that the Persians summoned mercenaries specifically from the Oxydrakai tribe, who were previously known to have resisted the incursions of Alexander the Great, but they never entered their armies into the region of Gandhara.[55]

During the reign of Xerxes I, Gandharan troops were noted by Herodotus to have taken part in the Second Persian invasion of Greece and were described as clothed similar to that of the Bactrians.[61] Herodotus states that during the battle they were led by the Achamenid general Artyphius.[62]

Under Persian rule, a system of centralized administration, with a bureaucratic system, was introduced into the Indus Valley for the first time. Provinces or "satrapy" were established with provincial capitals. The Gandhara satrapy, established 518 BCE with its capital at Pushkalavati (Charsadda).[63] It was also during the Achaemenid Empire rule of Gandhara that the Kharosthi script, the script of Gandhari prakrit, was born through the Aramaic alphabet.[64]

Hellenistic era Gandhāra

According to Arrian's Indica, the area corresponding to Gandhara situated between the Kabul River and the Indus River was inhabited by two tribes noted as the Assakenoi and Astakanoi whom he describes as 'Indian' and occupying the two great cities of Massaga located around the Swat valley and Pushkalavati in modern day Peshawar.[65]

The sovereign of Taxila, Omphis, formed an alliance with Alexander, motivated by a longstanding animosity towards Porus, who governed the region encompassed by the Chenab and Jhelum River.[66] Omphis, in a gesture of goodwill, presented Alexander the great with significant gifts, esteemed among the Indian populace, and subsequently accompanied him on the expedition crossing the Indus.[67]

In 327 BCE, Alexander the Great's military campaign progressed to Arigaum, situated in present-day Nawagai, marking the initial encounter with the Aspasians. Arrian documented their implementation of a scorched earth strategy, evidenced by the city ablaze upon Alexander's arrival, with its inhabitants already fleeing.[68] The Aspasians fiercely contested Alexander's forces, resulting in their eventual defeat. Subsequently, Alexander traversed the River Guraeus in the contemporary Dir District, engaging with the Asvakas, as chronicled in Sanskrit literature.[69] The primary stronghold among the Asvakas, Massaga, characterized as strongly fortified by Quintus Curtius Rufus, became a focal point.[70] Despite an initial standoff which led to Alexander being struck in the leg by an Asvaka arrow,[71] peace terms were negotiated between the Queen of Massaga and Alexander. However, when the defenders had vacated the fort, a fierce battle ensued when Alexander broke the treaty. According to Diodorus Siculus, the Asvakas, including women fighting alongside their husbands, valiantly resisted Alexander's army but were ultimately defeated.[72]

Mauryan Gandhāra

During the Mauryan era, Gandhara held a pivotal position as a core territory within the empire, with Taxila serving as the provincial capital of the North West.[73] Chanakya, a prominent figure in the establishment of the Mauryan Empire, played a key role by adopting Chandragupta Maurya, the initial Mauryan emperor. Under Chanakya's tutelage, Chandragupta received a comprehensive education at Taxila, encompassing various arts of the time, including military training, for a duration spanning 7–8 years.[74]

Plutarch's accounts suggest that Alexander the Great encountered a young Chandragupta Maurya in the Punjab region, possibly during his time at the university.[75] Subsequent to Alexander's death, Chanakya and Chandragupta allied with Trigarta king Parvataka to conquer the Nanda Empire.[76] This alliance resulted in the formation of a composite army, comprising Gandharans and Kambojas, as documented in the Mudrarakshasa.[77]

Bindusaras reign witnessed a rebellion among the locals of Taxila to which according to the Ashokavadana, he dispatched Ashoka to quell the uprising. Upon entering the city, the populace conveyed that their rebellion was not against Ashoka or Bindusara but rather against oppressive ministers.[78] In Ashoka's subsequent tenure as emperor, he appointed his son as the new governor of Taxila.[79] During this time, Ashoka erected numerous rock edicts in the region in the Kharosthi script and commissioned the construction of a monumental stupa in Pushkalavati, Western Gandhara, the location of which remains undiscovered to date.[80]

According to the Taranatha, following the death of Ashoka, the northwestern region seceded from the Maurya Empire, and Virasena emerged as its king.[81] Noteworthy for his diplomatic endeavors, Virasena's successor, Subhagasena, maintained relations with the Seleucid Greeks. This engagement is corroborated by Polybius, who records an instance where Antiochus III the Great descended into India to renew his ties with King Subhagasena in 206 BCE, subsequently receiving a substantial gift of 150 elephants from the monarch.[82][83]

Indo-Greek Kingdom

The Indo-Greek king Menander I (reigned 155–130 BCE) drove the Greco-Bactrians out of Gandhara and beyond the Hindu Kush, becoming king shortly after his victory.

His empire survived him in a fragmented manner until the last independent Greek king, Strato II, disappeared around 10 CE. Around 125 BCE, the Greco-Bactrian king Heliocles, son of Eucratides, fled from the Yuezhi invasion of Bactria and relocated to Gandhara, pushing the Indo-Greeks east of the Jhelum River. The last known Indo-Greek ruler was Theodamas, from the Bajaur area of Gandhara, mentioned on a 1st-century CE signet ring, bearing the Kharoṣṭhī inscription "Su Theodamasa" ("Su" was the Greek transliteration of the Kushan royal title "Shau" ("Shah" or "King")).

It is during this period that the fusion of Hellenistic and South Asian mythological, artistic and religious elements becomes most apparent, especially in the region of Gandhara.[citation needed]

Local Greek rulers still exercised a feeble and precarious power along the borderland, but the last vestige of the Greco-Indian rulers was finished by a people known to the old Chinese as the Yueh-Chi.[84]

Apracharajas

The Apracharajas were a historical dynasty situated in the region of Gandhara, extending from the governance of Menander II within the Indo-Greek Kingdom to the era of the early Kushans. Renowned for their significant support of Buddhism, this assertion is supported by swathes of discovered donations within their principal domain, between Taxila and Bajaur.[85] Archaeological evidence also establishes dynastic affiliations between them and the rulers of Oddiyana in modern-day Swat.[86]

The dynasty is argued to have been founded by Vijayakamitra, identified as a vassal to Menander II, according to the Shinkot casket. This epigraphic source further articulates that King Vijayamitra, a descendant of Vijayakamitra, approximately half a century subsequent to the initial inscription, is credited with its restoration following inflicted damage.[87] He is presumed to have gained the throne in c. 2 BCE after succeeding Visnuvarma, with a reign of three decades lasting til c. 32 CE [88] before being succeeded by his son Indravasu and then further by Indravasu's grandson Indravarma II in c. 50 CE.[89]

Indo-Scythian Kingdom

The Indo-Scythians were descended from the Sakas (Scythians) who migrated from Central Asia into South Asia from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century BCE. They displaced the Indo-Greeks and ruled a kingdom that stretched from Gandhara to Mathura. The first Indo-Scythian king Maues established Saka hegemony by conquering Indo-Greek territories.[90]

Some Aprachas are documented on the Silver Reliquary discovered at Sirkap, near Taxila, designating the title "Stratega," denoting a position equivalent to Senapati, such as that of Indravarma who was a general during the reign of the Apracharaja Vijayamitra.[91] Indravarma is additionally noteworthy for receiving the above-mentioned Silver Reliquary from the Indo-Scythian monarch Kharahostes, which he subsequently re-dedicated as a Buddhist reliquary, indicating was a gift in exchange for tribute or assistance.[92] According to another reliquary inscription Indravarma is noted as the Lord of Gandhara and general during the reign of Vijayamitra.[93] According to Apracha chronology, Indravarma was the son of Visnuvarma, an Aprachraja preceding Vijayamitra.

Indravarmas son Aspavarma is situated between 20 and 50 CE, during which numismatic evidence overlaps him with the Indo-Scythian ruler Azes II and Gondophares of the Indo-Parthians whilst also describing him as 'Stratega' or general of the Aprachas.[94] In accordance with a Buddhist Avadana, Aspavarma and a Saka noble, Jhadamitra, engaged in discussions concerning the establishment of accommodation for monks during the rainy seasons, displaying that he was a patron of Buddhism.[95] A reliquary inscription dedicated to 50 CE, by a woman named Ariasrava, describes that her donation was made during the reign of Gondophares nephew, Abdagases I, and Aspavarma, describing the joint rule by the Aprachas and the Indo-parthians.[96]

Indo-Parthian Kingdom

The Indo-Parthian Kingdom was ruled by the Gondopharid dynasty, named after its first ruler Gondophares. For most of their history, the leading Gondopharid kings held Taxila (in the present Punjab province of Pakistan) as their residence, but during their last few years of existence, the capital shifted between Kabul and Peshawar. These kings have traditionally been referred to as Indo-Parthians, as their coinage was often inspired by the Arsacid dynasty, but they probably belonged to wider groups of Iranic tribes who lived east of Parthia proper, and there is no evidence that all the kings who assumed the title Gondophares, which means "Holder of Glory", were even related.

During the dominion of the Indo-Parthians, Apracharaja Sasan, as described on numismatic evidence identifying him as the nephew of Aspavarma, emerged as a figure of significance.[97] Aspavarman, a preceding Apracharaja contemporaneous with Gondophares, was succeeded by Sasan, after having ascended from a subordinate governance role to a recognized position as one of Gondophares's successors.[98] He assumed the position following Abdagases I.[99] The Kushan ruler Vima Takto is known through numismatic evidence to have overstruck the coins of Sasan, whilst a numismatic hoard had found coins of Sasan together with smaller coins of Kujula Kadphises[100] It has also been discovered that Sasan overstruck the coins of Nahapana of the Western Satraps, this line of coinage dating between 40 and 78 CE.[101]

It was noted by Philostratus and Apollonius of Tyana upon their visit with Phraotes in 46 AD, that during this time the Gandharans living between the Kabul River and Taxila had coinage of Orichalcum and Black brass, and their houses appearing as single-story structures from the outside, but upon entering, underground rooms were also present.[102] They describe Taxila as being the same size as Nineveh, being walled like a Greek city whilst also being shaped with Narrow roads,[103][104] and further describe Phraotes kingdom as containing the old territory of Porus.[105] Following an exchange with the king, Phraotes is reported to have subsidized both barbarians and neighbouring states, to avert incursions into his kingdom.[106] Phraotes also recounts that his father, being the son of a king, had become an orphan from a young age. In accordance with Indian customs, two of his relatives assumed responsibility for his upbringing until they were killed by rebellious nobles during a ritualistic ceremony along the Indus River.[107] This event led to the usurpation of the throne, compelling Phraotes' father to seek refuge with the king situated beyond the Hydaspes River, in modern-day Punjab, a ruler esteemed greater than Phraotes' father. Moreover, Phraotes states that his father received an education facilitated by the Brahmins upon request to the king and married the daughter of the Hydaspian king, whilst having one son who was Phraotes himself.[108] Phraotes proceeds to narrate the opportune moment he seized to reclaim his ancestral kingdom, sparked by a rebellion of the citizens of Taxila against the usurpers. With fervent support from the populace, Phraotes led a triumphant entry into the residence of the usurpers, whilst the citizens brandished torches, swords, and bows in a display of unified resistance.[109]

Tribes mentioned by Pliny

During this period in the 1st century CE, Pliny the Elder notes a list of tribes in the Vahika and Gandhara regions spanning from the lower Indus to the mountain tribes near the Hindu Kush.

After passing this island, the other side of the Indus is occupied, as we know by clear and undoubted proofs, by the Athoae, the Bolingae, the Gallitalutae, the Dimuri, the Megari, the Ardabae, the Mesae, and after them, the Uri and the Silae; beyond which last there are desert tracts, extending a distance of two hundred and fifty miles. After passing these nations, we come to the Organagae, the Abortae, the Bassuertae, and, after these last, deserts similar to those previously 'mentioned. We then come to the peoples of the Sorofages, the Arbae, the Marogomatrae, the Umbrittae, of whom there are twelve nations, each with two cities, and the Asini, a people who dwell in three cities, their capital being Bucephala, which was founded around the tomb of the horse belonging to king Alexander, which bore that name. Above these peoples there are some mountain tribes, which lie at the foot of Caucasus, the Soseadae and the Sondrae, and, after passing the Indus and going down its stream, the Samarabriae, the Sambraceni, the Bisambritae, the Orsi, the Anixeni, and the Taxilae, with a famous city, which lies on a low but level plain, the general name of the district being Amenda: there are four nations here, the Peucolaitae, the Arsagalitae, the Geretae, and the Assoi.

— Pliny the elder, Natural history

Kushan Gandhāra

The Kushans conquered Bactria after having been defeated by the Xiongnu and forced to retreat from the Central Asian steppes. The Yuezhi fragmented the region of Bactria into five distinct territories, with each tribe of the Yuezhi assuming dominion over a separate kingdom.[110] However, a century after this division, Kujula Kadphises of the Kushan tribe emerged victorious by destroying the other four Yuezhi tribes and consolidating his reign as king.[111] Kujula then invaded Parthia and annexed the upper reaches of the Kabul River before further conquering Jibin.[112] In 78 CE the Indo-Parthians seceded Gandhara to the Kushans with Kujula Kadphises son Vima Takto succeeding the Apracharaja Sases in Taxila and further conquering Tianzhu (India) before installing a general as a satrap.[113][114]

According to the Xiyu Zhuan, the inhabitants residing in the upper reaches of the Kabul River were extremely wealthy and excelled in commerce, with their cultural practices bearing resemblance to those observed in Tianzhu (India). However, the text also characterizes them as weak and easily conquered with their political allegiance never being constant.[115] Over time, the region underwent successive annexations by Tianzhu, Jibin, and Parthia during periods of their respective strength, only to be lost when these powers experienced a decline.[116] The Xiyu Zhuan describes Tianzhu's customs as bearing similarities to that of the Yuezhi and the inhabitants riding on elephants in warfare.[117]

The Kushan period is considered the Golden Period of Gandhara. Peshawar Valley and Taxila are littered with ruins of stupas and monasteries of this period. Gandharan art flourished and produced some of the best pieces of sculpture from the Indian subcontinent. Gandhara's culture peaked during the reign of the great Kushan king Kanishka the Great (127 CE – 150 CE). The cities of Taxila (Takṣaśilā) at Sirsukh and Purushapura (modern-day Peshawar) reached new heights. Purushapura along with Mathura became the capital of the great empire stretching from Central Asia to Northern India with Gandhara being in the midst of it. Emperor Kanishka was a great patron of the Buddhist faith; Buddhism spread from India to Central Asia and the Far East across Bactria and Sogdia, where his empire met the Han Empire of China. Buddhist art spread from Gandhara to other parts of Asia. In Gandhara, Mahayana Buddhism flourished and Buddha was represented in human form. Under the Kushans new Buddhist stupas were built and old ones were enlarged. Huge statues of the Buddha were erected in monasteries and carved into the hillsides. Kanishka also built the 400-foot Kanishka stupa at Peshawar. This tower was reported by Chinese monks Faxian, Song Yun, and Xuanzang who visited the country. The stupa was built during the Kushan era to house Buddhist relics and was among the tallest buildings in the ancient world.[118][119][120]

- Head of a bodhisattva, c. 4th century CE

Kidarites

The Kidarites conquered Peshawar and parts of the northwest Indian subcontinent including Gandhara probably sometime between 390 and 410 from Kushan empire,[121] around the end of the rule of Gupta Emperor Chandragupta II or beginning of the rule of Kumaragupta I.[122] It is probably the rise of the Hephthalites and the defeats against the Sasanians which pushed the Kidarites into northern India. Their last ruler in Gandhara was Kandik, c. 500 CE.

Alchon Huns

Around 430 King Khingila, the most notable Alchon ruler, emerged and took control of the routes across the Hindu Kush from the Kidarites.[123][124][125][126] Coins of the Alchons rulers Khingila and Mehama were found at the Buddhist monastery of Mes Aynak, southeast of Kabul, confirming the Alchon presence in this area around 450–500 CE.[127] The numismatic evidence as well as the so-called "Hephthalite bowl" from Gandhara, now in the British Museum, suggests a period of peaceful coexistence between the Kidarites and the Alchons, as it features two Kidarite noble hunters, together with two Alchon hunters and one of the Alchons inside a medallion.[128] At one point, the Kidarites withdrew from Gandhara, and the Alchons took over their mints from the time of Khingila.[128]

The silver bowl in the British Museum

Alchon horseman.[128]

The so-called "Hephthalite bowl" from Gandhara, features two Kidarite hunters wearing characteristic crowns, as well as two Alchon hunters (one of them shown here, with skull deformation), suggesting a period of peaceful coexistence between the two entities.[128] Swat District, Pakistan, 460–479 CE. British Museum.[129][130]

The Alchons undertook the mass destruction of Buddhist monasteries and stupas at Taxila, a high centre of learning, which never recovered from the destruction.[131][132] Virtually all of the Alchon coins found in the area of Taxila were found in the ruins of burned down monasteries, where some of the invaders died alongside local defenders during the wave of destructions.[131] It is thought that the Kanishka stupa, one of the most famous and tallest buildings in antiquity, was destroyed by them during their invasion of the area in the 460s CE. The Mankiala stupa was also vandalized during their invasions.[133]

Mihirakula in particular is remembered by Buddhist sources to have been a "terrible persecutor of their religion" in Gandhara.[134] During the reign of Mihirakula, over one thousand Buddhist monasteries throughout Gandhara are said to have been destroyed.[135] In particular, the writings of Chinese monk Xuanzang from 630 CE explained that Mihirakula ordered the destruction of Buddhism and the expulsion of monks.[136] The Buddhist art of Gandhara, in particular Greco-Buddhist art, became extinct around this period. When Xuanzang visited Gandhara in c. 630 CE, he reported that Buddhism had drastically declined in favour of Shaivism and that most of the monasteries were deserted and left in ruins.[137] It is also noted by Kalhana that Brahmins of Gandhara accepted from Mihirakula gifts of Agraharams.[138] Kalhana also noted in his Rajatarangini how Mihirakula oppressed local Brahmins of South Asia and imported Gandharan Brahmins into Kashmir and India and states that he had given thousands of villages to these Brahmins in Kashmir.[139][140]

Turk and Hindu Shahis

The Turk Shahis ruled Gandhara until 843 CE when they were overthrown by the Hindu Shahis. The Hindu Shahis are believed to belong to the Uḍi/Oḍi tribe, namely the people of Oddiyana in Gandhara.[142][143]

The history of the Hindu Shahis begins in 843 CE with Kallar deposing the last Turk Shahi ruler, Lagaturman. Samanta succeeded him, and it was during his reign that the region of Kabul was lost to the Persianate Saffarid empire.[144] Lalliya replaced Samanta soon after and re-conquered Kabul whilst also subduing the region of Zabulistan.[145][146] He is additionally noteworthy for coming into conflict with Samkaravarman of the Utpala dynasty, resulting in his victory and the latter's death in Hazara and was the first Shahi noted by Kalhana. He is depicted as a great ruler with strength to the standard where kings of other regions would seek shelter in his capital of Udabhanda, a change from the previous capital of Kabul.[147][148] Bhimadeva, the next most notable ruler, is most significant for vanquishing the Samanid Empire in Ghazni and Kabul in response to their conquests,[149] his grand-daughter Didda was also the last ruler of the Lohara dynasty. Jayapala then gained control and was brought into conflict with the newly formed Ghaznavid Empire, however, he was eventually defeated. During his rule and that of his son and successor, Anandapala, the kingdom of Lahore was conquered. The following Shahi rulers all resisted the Ghaznavids but were ultimately unsuccessful, resulting in the downfall of the empire in 1026 CE.

Rediscovery

By the time Gandhara had been absorbed into the empire of Mahmud of Ghazni, Buddhist buildings were already in ruins and Gandhara's art had been forgotten. After Al-Biruni, the Kashmiri writer Kalhaṇa wrote his book Rajatarangini in 1151. He recorded some events that took place in Gandhara and provided details about its last royal dynasty and capital Udabhandapura.

In the 19th century, British soldiers and administrators started taking an interest in the ancient history of the Indian Subcontinent. In the 1830s coins of the post-Ashoka period were discovered, and in the same period, Chinese travelogues were translated. Charles Masson, James Prinsep, and Alexander Cunningham deciphered the Kharosthi script in 1838. Chinese records provided locations and site plans for Buddhist shrines. Along with the discovery of coins, these records provided clues necessary to piece together the history of Gandhara. In 1848 Cunningham found Gandhara sculptures north of Peshawar. He also identified the site of Taxila in the 1860s. From then on a large number of Buddhist statues were discovered in the Peshawar valley.

Archaeologist John Marshall excavated at Taxila between 1912 and 1934. He discovered separate Greek, Parthian, and Kushan cities and a large number of stupas and monasteries. These discoveries helped to piece together much more of the chronology of the history of Gandhara and its art.

After 1947 Ahmed Hassan Dani and the Archaeology Department at the University of Peshawar made several discoveries in the Peshawar and Swat Valley. Excavation of many of the sites of the Gandhara Civilization is being done by researchers from Peshawar and several universities around the world.

Culture

Summarize

Perspective

Language

Gandhara's language was a Prakrit or "Middle Indo-Aryan" dialect, usually called Gāndhārī.[150] Under the Kushan Empire, Gāndhārī spread into adjoining regions of South and Central Asia.[150] It used the Kharosthi script, which is derived from the Aramaic script, and it died out about in the 4th century CE.[150][151]

Hindko, historically spoken in Purushapura, the ancient capital of the Gandhara Civilization, has deep roots in the region's rich cultural and intellectual heritage. Derived from Shauraseni Prakrit, a Middle Indo-Aryan language of northern India, Hindko evolved from one of the key vernaculars of Sanskrit.[152][153] The Gandhara region's dynamic cultural and political shifts influenced Hindko's linguistic development. Today, Hindko which is known as Pishori, Kohati, Chacchi, Ghebi, Hazara Hindko, primarily spoken in parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, Pothohar Plateau, Hazara Division, especially where Gandhara Civilization took birth from, preserving its historical significance and reflecting the region's enduring linguistic legacy.[citation needed] Hindko, identifying shared phonological, morphological, and syntactical features that trace back to Prakrit languages. Inscriptions and manuscripts from the Gandhara region show linguistic patterns that link ancient Prakrit or Middle Indo Aryan to modern Hindko.[154][155][156]

Linguistic evidence links some groups of the Dardic languages with Gandhari.[157][158][159] The Kohistani languages, now all being displaced from their original homelands, were once more widespread in the region and most likely descend from the ancient dialects of the region of Gandhara.[160][161] The last to disappear was Tirahi, still spoken some years ago in a few villages in the vicinity of Jalalabad in eastern Afghanistan, by descendants of migrants expelled from Tirah by the Afridi Pashtuns in the 19th century.[162] Georg Morgenstierne claimed that Tirahi is "probably the remnant of a dialect group extending from Tirah through the Peshawar district into Swat and Dir".[163] Nowadays, it must be entirely extinct and the region is now dominated by Iranian languages brought in by later immigrations, such as Pashto.[162] Among the modern day Indo-Aryan languages still spoken today, Torwali shows the closest linguistic affinity possible to Niya, a dialect of Gāndhārī.[161][164]

Religion

Mahāyāna Buddhism

As per Pali sources, Buddhism first reached Gandhara following the Third Buddhist council which was held in Pataliputra during the reign of Ashoka in the third-century BCE.[165] Various monks were dispatched to different parts of the empire and the missionary dispatched to Gandhara specifically was Majjhantika who originated from the city of Varanasi in India.[166]

Mahāyāna Pure Land sutras were brought from the Gandhāra region to China as early as 147 CE, when the Kushan monk Lokakṣema began translating some of the first Buddhist sutras into Chinese.[167] The earliest of these translations show evidence of having been translated from the Gāndhārī language.[168] Lokakṣema translated important Mahāyāna sūtras such as the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra, as well as rare, early Mahāyāna sūtras on topics such as samādhi, and meditation on the Buddha Akṣobhya. Lokaksema's translations continue to provide insight into the early period of Mahāyāna Buddhism. This corpus of texts often includes and emphasizes ascetic practices forest dwelling, and absorption in states of meditative concentration:[169]

Paul Harrison has worked on some of the texts that are arguably the earliest versions we have of the Mahāyāna sūtras, those translated into Chinese in the last half of the second century AD by the Indo-Scythian translator Lokakṣema. Harrison points to the enthusiasm in the Lokakṣema sūtra corpus for the extra ascetic practices, for dwelling in the forest, and above all for states of meditative absorption (samādhi). Meditation and meditative states seem to have occupied a central place in early Mahāyāna, certainly because of their spiritual efficacy but also because they may have given access to fresh revelations and inspiration.

Some scholars believe that the Mahāyāna Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra was compiled in the age of the Kushan Empire in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, by order of Mahīśāsaka bhikṣus which flourished in the Gandhāra region.[170][171] However, it is likely that the longer Sukhāvatīvyūha owes greatly to the Mahāsāṃghika-Lokottaravāda sect as well for its compilation, and in this sutra, there are many elements in common with the Lokottaravādin Mahāvastu.[170] There are also images of Amitābha Buddha with the bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvara and Mahāsthāmaprāpta which were made in Gandhāra during the Kushan era.[172]

The Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa records that Kaniṣka of the Kushan Empire presided over the establishment of the Mahāyāna Prajñāpāramitā teachings in the northwest.[173] Tāranātha wrote that in this region, 500 bodhisattvas attended the council at Jālandhra monastery during the time of Kaniṣka, suggesting some institutional strength for Mahāyāna in the north-west during this period.[173] Edward Conze goes further to say that Prajñāpāramitā had great success in the north-west during the Kushan period, and may have been the "fortress and hearth" of early Mahāyāna, but not its origin, which he associates with the Mahāsāṃghika branch of Buddhism.[174]

Art

Gandhāra is noted for the distinctive Gandhāra style of Buddhist art, which shows the influence of Hellenistic and local Indian influences from the Gangetic Valley.[175] The Gandhāran art flourished and achieved its peak during the Kushan period, from the 1st to the 5th centuries, but it declined and was destroyed after the invasion of the Alchon Huns in the 5th century.

Siddhārtha shown as a bejeweled prince (before Siddhārtha renounces palace life) is a common motif.[176] Stucco, as well as stone, were widely used by sculptors in Gandhara for the decoration of monastic and cult buildings.[176][177] Buddhist imagery combined with some artistic elements from the cultures of the Hellenistic world. An example is the youthful Buddha, his hair in wavy curls, similar to statutes of Apollo.[176] Sacred artworks and architectural decorations used limestone for stucco composed by a mixture of local crushed rocks (i.e. schist and granite) which resulted compatible with the outcrops located in the mountains northwest of Islamabad.[178]

The artistic traditions of Gandhara art can be divided into the following phases:

- Indo-Greek art; 2nd century BCE to 1st century CE

- Indo-Scythian art; 1st century BCE to 1st century CE

- Kushan art; 1st century CE to 4th century CE

- Standing Bodhisattva (1st–2nd century)

- Buddha head (2nd century)

- Buddha head (4th–6th century)

- Buddha in acanthus capital

- The Greek god Atlas, supporting a Buddhist monument, Hadda

- The Bodhisattva Maitreya (2nd century)

- Wine-drinking and music, Hadda (1st–2nd century)

- Maya's white elephant dream (2nd–3rd century)

- The birth of Siddhārtha (2nd–3rd century)

- The Great Departure from the Palace (2nd–3rd century)

- The end of asceticism (2nd–3rd century)

- The Buddha preaching at the Deer Park in Sarnath (2nd–3rd century)

- Scene of the life of the Buddha (2nd–3rd century)

- The death of the Buddha, or parinirvana (2nd–3rd century)

- A sculpture from Hadda, (3rd century)

- The Bodhisattva and Chandeka, Hadda (5th century)

- Hellenistic decorative scrolls from Hadda, Afghanistan

- Hellenistic scene, Gandhara (1st century)

- A stone plate (1st century)

- "Laughing boy" from Hadda

- Bodhisattva seated in meditation

- Marine deities, Gandhara

- The Seated Buddha, dating from 300 to 500 CE, was found near Jamal Garhi, and is now on display at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco.

- Sharing of the Buddha's relics, above a Gandhara fortified city

Major cities

Major cities of ancient Gandhara are as follows:

- Puṣkalavati (Charsadda), Pakistan

- Takshashila (Taxila), Pakistan

- Puruṣapura (Peshawer), Pakistan

- Sagala (Sialkot), Pakistan

- Oddiyana (Swat), Pakistan

- Jibin, Pakistan appears in the Chinese sources

- Chukhsa (Chhachh), Pakistan

- Attock Khurd (Attock), Pakistan

- Hund (Swabi), Pakistan

- Bajaur, capital of (Apraca), Pakistan

- Aornos, somewhere in Hazara, Pakistan

Notable people

In popular culture

See also

References

Sources

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.