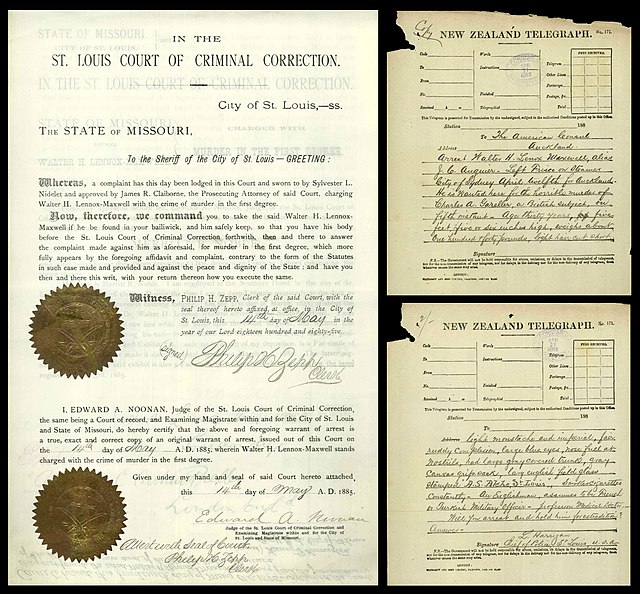

Extradition

Transfer of a suspect from one jurisdiction to another by law enforcement From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In an extradition, one jurisdiction delivers a person accused or convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, into the custody of the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforcement procedure between the two jurisdictions, and depends on the arrangements made between them. In addition to legal aspects of the process, extradition also involves the physical transfer of custody of the person being extradited to the legal authority of the requesting jurisdiction.[1]

In an extradition process, one sovereign jurisdiction makes a formal request to another sovereign jurisdiction ("the requested state"). If the fugitive is found within the territory of the requested state, then the requested state may arrest the fugitive and subject them to its extradition process.[2] The extradition procedures to which the fugitive will be subjected are dependent on the law and practice of the requested state.[2]

Between countries, extradition is normally regulated by treaties. Where extradition is compelled by laws, such as among sub-national jurisdictions, the concept may be known more generally as rendition. It is an ancient mechanism, dating back to at least the 13th century BCE, when an Egyptian pharaoh, Ramesses II, negotiated an extradition treaty with a Hittite king, Hattusili III.[2]

Extradition treaties or agreements

Summarize

Perspective

The consensus in international law is that a state does not have any obligation to surrender an alleged criminal to a foreign state, because one principle of sovereignty is that every state has legal authority over the people within its borders. Such absence of international obligation, and the desire for the right to demand such criminals from other countries, have caused a web of extradition treaties or agreements to evolve. When no applicable extradition agreement is in place, a state may still request the expulsion or lawful return of an individual pursuant to the requested state's domestic law.[2] This can be accomplished through the immigration laws of the requested state or other facets of the requested state's domestic law. Similarly, the codes of penal procedure in many countries contain provisions allowing for extradition to take place in the absence of an extradition agreement.[2] States may, therefore, still request the expulsion or lawful return of a fugitive from the territory of a requested state in the absence of an extradition treaty.[2]

No country in the world has an extradition treaty with all other countries; for example, the United States lacks extradition treaties with China, Russia, Namibia, the United Arab Emirates, North Korea, Bahrain, and many other countries.[3]

There are two types of extradition treaties: list and dual criminality treaties. The most common and traditional is the list treaty, which contains a list of crimes for which a suspect is to be extradited. Dual criminality treaties generally allow for the extradition of a criminal suspect if the punishment is more than one year imprisonment in accordance with the laws of both countries. Occasionally the length of the sentence agreed upon between the two countries is varied. Under both types of treaties, if the conduct is not considered a crime in both of the countries involved then it will not be an extraditable offense.[citation needed]

Generally, an extradition treaty requires that a country seeking extradition be able to show that:

- The relevant crime is sufficiently serious.

- There exists a prima facie case against the individual sought.

- The event in question qualifies as a crime in both countries.

- The extradited person can reasonably expect a fair trial in the recipient country.

- The likely penalty will be proportionate to the crime.

Restrictions

Most countries require themselves to deny extradition requests if, in the government's opinion, the suspect is being sought for a political crime. Many countries, such as Mexico, Canada and most European nations, will not allow extradition if the death penalty may be imposed on the suspect unless they are assured that the death sentence will not be passed or carried out. In the case of Soering v. United Kingdom, the European Court of Human Rights held that it would violate Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights to extradite a person to the United States from the United Kingdom in a capital case. This was due to the harsh conditions on death row and the uncertain timescale within which the sentence would be executed. Parties to the European Convention also cannot extradite people where they would be at significant risk of being tortured inhumanely or degradingly treated or punished.

These restrictions are normally clearly spelled out in the extradition treaties that a government has agreed upon. They are, however, controversial in the United States, where the death penalty is practiced in some U.S. states, as it is seen by many as an attempt by foreign nations to interfere with the U.S. criminal justice system. In contrast, pressures by the U.S. government on these countries to change their laws, or even sometimes to ignore their laws, is perceived by many in those nations as an attempt by the United States to interfere in their sovereign right to manage justice within their own borders. Famous examples include the extradition dispute with Canada on Charles Ng, who was eventually extradited to the United States on murder charges.

Countries with a rule of law typically make extradition subject to review by that country's courts. These courts may impose certain restrictions on extradition, or prevent it altogether, if for instance they deem the accusations to be based on dubious evidence, or evidence obtained from torture, or if they believe that the defendant will not be granted a fair trial on arrival, or will be subject to cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment if extradited.

Several countries, such as France, the Russian Federation, Austria, China and Japan, have laws against extraditing their respective citizens. Others, such as Germany and Israel, do not allow for extradition of their own citizens in their constitutions. Some others stipulate such prohibition on extradition agreements rather than their laws. Such restrictions are occasionally controversial in other countries when, for example, a French citizen commits a crime abroad and then returns to their home country, often being perceived as doing so to avoid prosecution. These countries, however, make their criminal laws applicable to citizens abroad, and they try citizens suspected of crimes committed abroad under their own laws. Such suspects are typically prosecuted as if the crime had occurred within the country's borders.

Exemptions in the European Union

The usual extradition agreement safeguards relating to dual-criminality, the presence of prima facie evidence and the possibility of a fair trial have been waived by many European nations for a list of specified offences under the terms of the European Arrest Warrant. The warrant entered into force in eight European Union (EU) member-states on 1 January 2004, and is in force in all member-states since 22 April 2005. Defenders of the warrant argue that the usual safeguards are not necessary because every EU nation is committed by treaty, and often by legal and constitutional provisions, to the right to a fair trial, and because every EU member-state is subject to the European Convention on Human Rights.

Extradition to federations

The federal structure of some countries, such as the United States, can pose particular problems for extraditions when the police power and the power of foreign relations are held at different levels of the federal hierarchy. For instance, in the United States, most criminal prosecutions occur at the state level, and most foreign relations occurs on the federal level. In fact, under the United States Constitution, foreign countries may not have official treaty relations with the individual states; rather, they may have treaty relations only with the federal government. As a result, a US state that wishes to prosecute an individual located in foreign territory must direct its extradition request through the federal government, which will negotiate the extradition with the requested state. However, due to the constraints of federalism, any conditions on the extradition accepted by the federal government – such as not to impose the death penalty – are not binding on the states. In the case of Soering v. United Kingdom, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the United Kingdom was not permitted under its treaty obligations to extradite an individual to the United States, because the United States' federal government was constitutionally unable to offer binding assurances that the death penalty would not be sought in Virginia state courts. Ultimately, the Commonwealth of Virginia itself had to offer assurances to the federal government, which passed those assurances on to the United Kingdom, which then extradited the individual to the United States.

Less important problems can arise due to differing qualifications for crimes. For instance, in the United States, crossing state lines is a prerequisite for certain federal crimes (otherwise crimes such as murder, etc. are handled by state governments (except in certain circumstances such as the killing of a federal official)[citation needed]. This transportation clause is, understandably, absent from the laws of many countries, however. Extradition treaties or subsequent diplomatic correspondence often include language providing that such criteria should not be taken into account when checking if the crime is one in the country from which extradition should apply.

Bars to extradition

Summarize

Perspective

By enacting laws or in concluding treaties or agreements, countries determine the conditions under which they may entertain or deny extradition requests. Observing fundamental human rights is also an important reason for denying some extradition requests. It is common for human rights exceptions to be specifically incorporated in bilateral treaties.[4] Such bars can be invoked in relation to the treatment of the individual in the receiving country, including their trial and sentence. These bars may also extend to take account of the effect on family of the individual if extradition proceeds. Therefore, human rights recognised by international and regional agreements may be the basis for denying extradition requests. However, cases where extradition is denied should be treated as independent exceptions and will only occur in exceptional circumstances.[5]

Common bars to extradition include:

Failure to fulfill dual criminality

Generally the act for which extradition is sought must constitute a crime punishable by some minimum penalty in both the requesting and the requested states.

This requirement has been abolished for broad categories of crimes in some jurisdictions, notably within the European Union.

Political nature of the alleged crime

Many countries refuse to extradite suspects of political crimes. Such exceptions aim to prevent the misuse of extradition for political purposes, protecting individuals from being prosecuted or punished for their political beliefs or activities in another country. Countries may refuse extradition to avoid becoming involved in politically motivated cases, or gaining a bargaining chip over a rival state.

Possibility of certain forms of punishment

Some countries refuse extradition on grounds that the person, if extradited, may receive capital punishment or face torture. A few go as far as to cover all punishments that they themselves would not administer.

- Death penalty: Several jurisdictions, such as Australia,[6] Canada, Macao,[7] New Zealand,[8] South Africa, United Kingdom and most European nations except Belarus, will not consent to the extradition of a suspect if the death penalty is a possible sentencing option unless they are assured that the death sentence will not be passed or carried out. The United Nations Human Rights Committee considered the case of Joseph Kindler, following the Canadian Supreme Court's decision in Kindler v Canada to extradite Kindler who faced the death penalty in the United States. This decision was given despite the fact that it was expressly provided in the extradition treaty between these two states that extradition may be refused, unless assurances were given that the death penalty shall not be imposed or executed, as well as arguably being a violation of the individual's rights under the Canadian Charter of Human Rights.[9] The decision by the Committee considered Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the "inherent right to life" and whether this right prohibited Canada from extraditing the individual to the United States where he faced the death penalty. The Committee decided that there was nothing contained in the terms of Article 6 which required Canada to seek assurance that the individual would not face the death penalty if extradited.[10] However, the Committee noted that if Canada had extradited without due process it would have breached its obligation under the Convention in this case.

- Torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment: Many countries will not extradite if there is a risk that a requested person will be subjected to torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. In regard to torture the European Court of Human Rights has in the past not accepted assurances that torture will not occur when given by a state where torture is systematic or endemic.[11] Although in the more recent case before the same court Othman (Abu Qatada) v. United Kingdom the court retreated from this firm refusal and instead took a more subjective approach for assessing state assurances. Unlike capital punishment it is often more difficult to prove the existence of torture within a state and considerations often depend on the assessment of quality and validity of assurances given by the requesting state. In the deportation case of Othman (Abu Qatada) the court provided 11 factors the court will assess in determining the validity of these assurances.[12] While torture is provided for as a bar to extradition by the European Convention on Human Rights and more universally by the Convention Against Torture, it is also a jus cogens norm under international law and can therefore be invoked as a bar even if it is not provided for in an extradition agreement.[5] In the case of Soering v United Kingdom, the European Court of Human Rights held that it would violate Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights to extradite a person to the United States from the United Kingdom in a capital punishment case. This was due to the harsh conditions on death row and the uncertain timescale within which the sentence would be executed, but not the death penalty sentence itself. The Court in Soering stressed however that the personal circumstances of the individual, including age and mental state (the individual in this case was 18 years old) were relevant in assessing whether their extradition would give rise to a real risk of treatment exceeding the threshold in Article 3.[13]

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction over a crime can be invoked to refuse extradition.[14]

Own citizens

Several countries, such as Austria,[15] Brazil,[16] Bulgaria,[17] Czechia (the Czech Republic),[18] France,[19][20] Germany,[21] Israel, Japan,[22] Morocco,[23] Norway,[24] the People's Republic of China (Mainland China),[25] Portugal,[26] the Republic of China (Taiwan),[27] Russia,[28] Saudi Arabia,[29] Slovenia, Switzerland,[30] Syria,[31] Turkey,[32] the UAE, and Vietnam[33] have laws against extraditing their own citizens to other countries' jurisdictions. Instead, they often have special laws in place that give them jurisdiction over crimes committed abroad by or against citizens. By virtue of such jurisdiction, they can locally prosecute and try citizens accused of crimes committed abroad as if the crime had occurred within the country's borders (see, e.g., trial of Xiao Zhen). Israeli law permits the extradition of Israeli citizens who have not established residency in Israel; resident citizens may be extradited to stand trial in a foreign country, provided that the prosecuting country agrees that any prison sentence imposed will be served in Israel.[34][35]

Right to private and family life

In a limited number of cases Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights has been invoked to stop extradition from proceeding. Article 8 states that everyone has the right to the respect of their private and family life. This is achieved by way of balancing the potential harm to private life against the public interest in upholding the extradition arrangement.[11] While this article is useful as it provide for a prohibition to extradition, the threshold required to meet this prohibition is high.[11] Article 8 does explicitly provide that this right is subject to limits in the interests of national security and public safety, so these limits must be weighed in a balancing of priority against this right. Cases where extradition is sought usually involve serious crimes so while these limits are often justified there have been cases where extradition could not be justified in light of the individual's family life. Cases to date have mostly involved dependant children where the extradition would be counter to the best interests of this child.[11] In the case of FK v. Polish Judicial Authority the court held that it would violate article 8 for a mother of five young children to be extradited amidst charges of minor fraud which were committed a number of years ago.[36] This case is an example of how the gravity of the crime for which extradition was sought was not proportionate to protecting the interests of the individual's family. However the court in this case noted that even in circumstances where extradition is refused a custodial sentence will be given to comply with the principles of international comity.[37] In contrast the case of HH v Deputy Prosecutor of the Italian Republic, Genoa is an example of when the public interest for allowing extradition outweighed the best interests of the children. In this case both parents were being extradited to Italy for serious drug importation crimes.[38] Article 8 does not only address the needs of children, but also all family members, yet the high threshold required to satisfy Article 8 means that the vulnerability of children is the most likely circumstance to meet this threshold. In the case of Norris v US (No 2) a man sought to argue that if extradited his health would be undermined and it would cause his wife depression.[39] This claim was rejected by the Court which stated that a successful claim under Article 8 would require "exceptional" circumstances.[40]

Suicide Risk: Cases where there is risk of the individual committing suicide have also invoked article 8 as the public interest of extraditing must be considered in light of the risk of suicide by the individual if extradited. In the case of Jason's v Latvia extradition was refused on these grounds, as the crime for which the individual was sought was not enough of a threat to public interest to outweigh the high risk of suicide which had been assessed to exist for the individual if extradited.[41]

Fair trial standards

Consideration of the right to a fair trial is particularly complex in extradition cases. Its complexity arises from the fact that while the court deciding whether to surrender the individual must uphold these rights this same court must also be satisfied that any trial undertaken by the requesting state after extradition is granted also respects these rights. Article 14 of the ICCPR provides a number of criteria for fair trial standards.[42] These standards have been reflected in courts who have shown that subjective considerations should be made in determining whether such trials would be ‘unjust’ or ‘oppressive’ by taking into account factors such as the duration of time since the alleged offences occurred, health of the individual, prison conditions in the requesting state and likelihood of conviction among other considerations.[43] Yet exactly how the standards provided for in ICCPR are incorporated or recognised by domestic courts and decision makers is still unclear although it seems that these standards can at a minimum be used to inform the notions of such decision makers.[4]: 35 If it is found that fair trial standards will not be satisfied in the requesting country this may be a sufficient bar to extradition.

Article 6 of the ECHR also provides for fair trial standards, which must be observed by European countries when making an extradition request.[4] This court in the Othman case, whom if extradited would face trial where evidence against him had been obtained by way of torture.[44] This was held to be a violation of Article 6 ECHR as it presented a real risk of a ‘flagrant denial of justice’.[11] The court in Othman stressed that for a breach of Article 6 to occur the trial in the requesting country must constitute a flagrant denial of justice, going beyond merely an unfair trial.[45] Evidence obtained by way of torture has been sufficient to satisfy the threshold of a flagrant denial of justice in a number of case. This is in part because torture evidence threatens the "integrity of the trial process and the rule of law itself."[46]

Human rights and extradition

Summarize

Perspective

Human rights as a bar to extradition can be invoked in relation to the treatment of the individual in the receiving country, including their trial and sentence as well as the effect on family of the individual if extradition is granted. The repressive nature and the limitations of freedoms imposed on an individual is part of the extradition process and is the reason for these exceptions and the importance that human rights are observed in the extradition process. Therefore, human rights protected by international and regional agreements may be the basis for denying extradition requests, but only as independent exceptions.[5] While human rights concerns can add to the complexity of extradition cases it is positive as it adds to the legitimacy and institutionalisation of the extradition system.[47]

Determining whether to allow extradition by the requested state is, among other considerations, a balancing exercise between the interests of the requesting state's pursuit of justice over the accused individuals, the requested state's interests in holding dominion over those presently in its territory, and the rights of the extraditable persons.[48] Extradition raises human rights concerns in determining this balance in relation to the extraditable person. States make provision to recognise these rights both expressing in bilateral treaty agreements and also, potentially by way of state's obligations under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, of which the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights is particularly relevant to extradition.[4] Although regional, the European Convention of Human Rights has also been invoked as a bar to extradition in a number of cases falling within its jurisdiction and decisions from the European Court of Human Rights have been a useful source of development in this area.

Aut dedere aut judicare

Summarize

Perspective

A concept related to extradition that has significant implications in transnational criminal law is that of aut dedere aut judicare.[2] This maxim represents the principle that states must either surrender a criminal within their jurisdiction to a state that wishes to prosecute the criminal or prosecute the offender in its own courts. Many international agreements contain provisions for aut dedere aut judicare. These include all four 1949 Geneva Conventions, the U.N. Convention for the Suppression of Terrorist Bombings, the U.N. Convention Against Corruption, the Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Seizure of Aircraft, the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of an Armed Conflict, and the International Convention for the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid.[2]

Some contemporary scholars hold the opinion that aut dedere aut judicare is not an obligation under customary international law but rather "a specific conventional clause relating to specific crimes" and, accordingly, an obligation that only exists when a state has voluntarily assumed the obligation. Cherif Bassiouni, however, has posited that, at least with regard to international crimes, it is not only a rule of customary international law but a jus cogens principle. Professor Michael Kelly, citing Israeli and Austrian judicial decisions, has noted that "there is some supporting anecdotal evidence that judges within national systems are beginning to apply the doctrine on their own".[2]

Controversies

Summarize

Perspective

International tensions

The refusal of a country to extradite suspects or criminals to another may lead to international relations being strained. Often, the country to which extradition is refused will accuse the other country of refusing extradition for political reasons (regardless of whether or not this is justified). A case in point is that of Ira Einhorn, in which some US commentators pressured President Jacques Chirac of France, who does not intervene in legal cases, to permit extradition when the case was held up due to differences between French and American human rights law. Another long-standing example is Roman Polanski whose extradition was pursued by California for over 20 years. For a brief period he was placed under arrest in Switzerland, however subsequent legal appeals there prevented extradition.

The questions involved are often complex when the country from which suspects are to be extradited is a democratic country with a rule of law. Typically, in such countries, the final decision to extradite lies with the national executive (prime minister, president or equivalent). However, such countries typically allow extradition defendants recourse to the law, with multiple appeals. These may significantly slow down procedures. On the one hand, this may lead to unwarranted international difficulties, as the public, politicians and journalists from the requesting country will ask their executive to put pressure on the executive of the country from which extradition is to take place, while that executive may not in fact have the authority to deport the suspect or criminal on their own. On the other hand, certain delays, or the unwillingness of the local prosecution authorities to present a good extradition case before the court on behalf of the requesting state, may possibly result from the unwillingness of the country's executive to extradite.

Even though the United States has an extradition treaty with Japan, most extraditions are not successful due to Japan's domestic laws. For the United States to be successful, they must present their case for extradition to the Japanese authorities. However, certain evidence is barred from being in these proceedings such as the use of confessions, searches or electronic surveillance. In most cases involving international drug trafficking, this kind of evidence constitutes the bulk of evidence gathered in the investigation on a suspect for a drug-related charge. Therefore, this usually hinders the United States from moving forward with the extradition of a suspect.[49]

There is at present controversy in the United Kingdom about the Extradition Act 2003,[50] which dispenses with the need for a prima facie case for extradition. This came to a head over the extradition of the Natwest Three from the UK to the U.S., for their alleged fraudulent conduct related to Enron. Several British political leaders were heavily critical of the British government's handling of the issue.[51]

In 2013, the United States submitted extradition requests to many nations for former National Security Agency employee Edward Snowden.[52] It criticized Hong Kong for allowing him to leave despite an extradition request.[53]

Extradition case of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou

It is a part of the China–United States trade war, which is political in nature.

2019 Hong Kong extradition law protests

A proposed Hong Kong extradition law tabled in April 2019 led to one of the biggest protests in the city's history, with 1 million demonstrators joining the protests on 9 June 2019.[54] They took place three days before the Hong Kong government planned to bypass the committee process and bring the contentious bill straight to the full legislature to hasten its approval.[54]

The bill, which would ease extradition to Mainland China, includes 37 types of crimes. While the Beijing-friendly ruling party maintains that the proposal contains protections of the dual criminality requirement and human rights, its opponents allege that after people are surrendered to the mainland, it could charge them with some other crime and impose the death penalty (which has been abolished in Hong Kong) for that other crime.[55] There are also concerns about the retroactive effect of the new law.[56]

The government's proposal was amended to remove some categories after complaints from the business sector, such as "the unlawful use of computers".[56]

Experts have noted that the legal systems of mainland China and Hong Kong follow 'different protocols' with regard to the important conditions of double criminality and non-refoulement, as well as on the matter of executive vs. judicial oversight on any extradition request.[57]

Abductions

In some cases a state has abducted an alleged criminal from the territory of another state either after normal extradition procedures failed, or without attempting to use them. Notable cases are listed below:

| Name | Year | From | To |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morton Sobell | 1950 | Mexico | United States |

| Adolf Eichmann | 1960 | Argentina | Israel |

| Antoine Argoud | 1963 | West Germany | France |

| Isang Yun | 1967[58] | West Germany | South Korea |

| Mordechai Vanunu | 1986 | Italy | Israel |

| Humberto Álvarez Machaín | 1990 | Mexico | United States |

| Abdullah Öcalan | 1999 | Kenya | Turkey |

| Wang Bingzhang | 2002 | Vietnam | China |

| Hassan Mustafa Osama Nasr | 2003 | Italy | Egypt |

| Rodrigo Granda | 2004 | Venezuela | Colombia |

| Konstantin Yaroshenko | 2008 | Liberia | United States |

| Dirar Abu Seesi | 2011 | Ukraine | Israel |

| Gui Minhai | 2015 | Thailand | China |

| Trịnh Xuân Thanh | 2017 | Germany | Vietnam |

"Extraordinary rendition"

"Extraordinary rendition" is an extrajudicial procedure in which criminal suspects, generally suspected terrorists or supporters of terrorist organisations, are transferred from one country to another.[59] The procedure differs from extradition as the purpose of the rendition is to extract information from suspects, while extradition is used to return fugitives so that they can stand trial or fulfill their sentence. The United States' Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) allegedly operates a global extraordinary rendition programme, which from 2001 to 2005 captured an estimated 150 people and transported them around the world.[60][61][62][63]

The alleged US programme prompted several official investigations in Europe into alleged secret detentions and illegal international transfers involving Council of Europe member states. A June 2006 report from the Council of Europe estimated 100 people had been kidnapped by the CIA on EU territory (with the cooperation of Council of Europe members), and rendered to other countries, often after having transited through secret detention centres ("black sites") used by the CIA, some of which could be located in Europe. According to the separate European Parliament report of February 2007, the CIA has conducted 1,245 flights, many of them to destinations where suspects could face torture, in violation of article 3 of the United Nations Convention Against Torture.[64] A large majority of the European Union Parliament endorsed the report's conclusion that many member states tolerated illegal actions by the CIA, and criticised such actions. Within days of his inauguration, President Obama signed an Executive Order opposing rendition torture and established a task force to provide recommendations about processes to prevent rendition torture.[65]

Uyghur extradition

In June 2021, CNN reported testimonies of several Uyghurs accounting for the detention and extradition of people they knew or were related to, from the United Arab Emirates. Documents issued by the Dubai public prosecutor and viewed by CNN, showed the confirmation of China’s request for the extradition of a detained Uyghur man, Ahmad Talip, despite insufficient proof of reasons for extradition.[66]

In 2019, UAE, along with several other Muslim nations publicly endorsed China's Xinjiang policies, despite Beijing being accused of genocide by the US State Department. Neither Dubai authorities nor the foreign ministry of UAE respond to the several requests for comment made by CNN on the detention and extradition of Uyghurs.[66]

See also

- Deportation

- Extraterritorial jurisdiction

- Extraterritoriality

- Immunity from prosecution

- Right of asylum

- Universal jurisdiction

- Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain

International

- European Arrest Warrant

- European Convention on Extradition

- Extradition law in Australia

- Extradition law in China

- Extradition law in Japan

- Extradition law in Israel

- Extradition law in Ireland

- Extradition law in the United States (including inter-state extradition)

- Extradition law in Nigeria

- Extradition law in the Philippines

Lists

- List of Australian extradition treaties

- List of Hong Kong extradition treaties

- List of Indian extradition treaties

- List of Dutch extradition treaties

- List of United States extradition treaties

Individuals:

- Luis Posada Carriles, anti-Castrist detained in the U.S. and wanted by Cuba and Venezuela

- Brian O'Rourke (1540?–1591), first man to be extradited within Britain

- Ramil Safarov, Azerbaijani officer extradited from Hungary to Azerbaijan

Protest:

Footnotes

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.