Einsatzgruppen trial

Ninth of the 12 trials for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by the Nazis From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The United States of America vs. Otto Ohlendorf, et al., commonly known as the Einsatzgruppen trial, was the ninth of the twelve "subsequent Nuremberg trials" for war crimes and crimes against humanity after the end of World War II between 1947 and 1948. The accused were 24 former SS leaders who, as commanders of the Einsatzgruppen, were responsible for the mass killing of more than a million victims in the Eastern Front.[1]

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (March 2022) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Einsatzgruppen trial | |

|---|---|

| |

Ohlendorf testifying on his own behalf | |

Paul Blobel is sentenced to death. |

The Einsatzgruppen trial was held by United States authorities at the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg in the American occupation zone before US military courts, not before the International Military Tribunal. All of the accused were found guilty: fourteen were sentenced to death by hanging and eight received prison sentences ranging from life imprisonment to time served. Two were only convicted of being a member of an illegal organization, one committed suicide before the arraignment, and one was removed from the trial for medical reasons. Otto Ohlendorf, Erich Naumann, Paul Blobel, and Werner Braune were executed in 1951 while the others sentenced to death had their sentences commuted.

The trial marked the first use of the term "genocide" in legal context, being used by both the prosecution and by the judges in the verdict.[2]

The case

Summarize

Perspective

The Einsatzgruppen were SS mobile death squads, operating behind the front line in Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe. From 1941 to 1945, they murdered around 2 million people; 1.3 million Jews, up to 250,000 Romani, and around 500,000 so-called "partisans", people with disabilities, political commissars, Slavs, homosexuals and others.[3][4] The 24 defendants in this trial were all commanders of these Einsatzgruppen units and faced charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The tribunal stated in its judgment:

... in this case the defendants are not simply accused of planning or directing wholesale killings through channels. They are not charged with sitting in an office hundreds and thousands of miles away from the slaughter. It is asserted with particularity that these men were in the field actively superintending, controlling, directing, and taking an active part in the bloody harvest.[5]

The judges in this case, heard before Military Tribunal II-A, were Michael Musmanno (presiding judge and naval officer) from Pennsylvania, John J. Speight from Alabama, and Richard D. Dixon from North Carolina. The chief of counsel for the prosecution was Telford Taylor; the chief prosecutor for this case was Benjamin B. Ferencz. The indictment was filed initially on July 3 and then amended on July 29, 1947, to also include the defendants Steimle, Braune, Haensch, Strauch, Klingelhöfer, and von Radetzky. The trial lasted from September 29, 1947, until April 10, 1948.

Indictment

- Crimes against humanity through persecutions on political, racial, and religious grounds, murder, extermination, imprisonment, and other inhumane acts committed against civilian populations, including German nationals and nationals of other countries, as part of an organized scheme of genocide.

- War crimes for the same reasons, and for wanton destruction and devastation not justified by military necessity.

- Membership of criminal organizations, the SS, the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), or the Gestapo, which had been declared criminal organizations previously in the international Nuremberg Military Tribunals.

All defendants were charged on all counts. All defendants pleaded "not guilty". The tribunal found all of them guilty on all counts, except Rühl and Graf, who were found guilty only on count 3. Fourteen defendants were sentenced to death. However, only four of them were executed. Nine of those condemned had their sentences reduced. Another, Eduard Strauch, couldn't be executed since he had been transferred to Belgian custody after his conviction.

Defendants

Summarize

Perspective

| Name | Photo | Function | Sentence | Outcome, 1951 amnesty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Otto Ohlendorf |  |

SS-Gruppenführer; member of the SD; commanding officer of Einsatzgruppe D | Death by hanging | Executed on June 7, 1951[6] |

| Heinz Jost |  |

SS-Brigadeführer; member of the SD; commanding officer of Einsatzgruppe A | Life imprisonment | Commuted to 10 years; released in December 1951; died in 1964 |

| Erich Naumann |  |

SS-Brigadeführer; member of the SD; commanding officer of Einsatzgruppe B | Death by hanging | Executed on June 7, 1951[6] |

| Otto Rasch |  |

SS-Brigadeführer; member of the SD and the Gestapo; commanding officer of Einsatzgruppe C | Removed from the trial on February 5, 1948 for medical reasons | Died on November 1, 1948 |

| Erwin Schulz |  |

SS-Brigadeführer; member of the Gestapo; commanding officer of Einsatzkommando 5 of Einsatzgruppe C | 20 years | Commuted to 15 years; released on January 9, 1954; died in 1981 |

| Franz Six |  |

SS-Brigadeführer; member of the SD; commanding officer of Vorkommando Moskau of Einsatzgruppe B | 20 years | Commuted to 10 years; released in October 1952; died in 1975 |

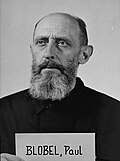

| Paul Blobel |  |

SS-Standartenführer; member of the SD; commanding officer of Sonderkommando 4a of Einsatzgruppe C | Death by hanging | Executed on June 7, 1951[6] |

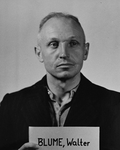

| Walter Blume |  |

SS-Standartenführer; member of the SD and the Gestapo; commanding officer of Sonderkommando 7a of Einsatzgruppe B | Death by hanging | Commuted to 25 years; released in March 1955; died in 1974 |

| Martin Sandberger |  |

SS-Standartenführer; member of the SD; commanding officer of Sonderkommando 1a of Einsatzgruppe A | Death by hanging | Commuted to life imprisonment; released on May 9, 1958; died in 2010 |

| Willi Seibert |  |

SS-Standartenführer; member of the SD; deputy chief of Einsatzgruppe D | Death by hanging | Commuted to 15 years; released on May 14, 1954; died in 1976 |

| Eugen Steimle |  |

SS-Standartenführer; member of the SD; commanding officer of Sonderkommando 7a of Einsatzgruppe B and of Sonderkommando 4a of Einsatzgruppe C | Death by hanging | Commuted to 20 years; released in June 1954; died in 1987 |

| Ernst Biberstein |  |

SS-Obersturmbannführer; member of the SD; commanding officer of Einsatzkommando 6 of Einsatzgruppe C | Death by hanging | Commuted to life imprisonment; released on May 9, 1958; died in 1986 |

| Werner Braune |  |

SS-Obersturmbannführer; member of the SD and the Gestapo; commanding officer of Einsatzkommando 11b of Einsatzgruppe D | Death by hanging | Executed on June 7, 1951[6] |

| Walter Haensch |  |

SS-Obersturmbannführer; member of the SD; commanding officer of Sonderkommando 4b of Einsatzgruppe C | Death by hanging | Commuted to 15 years; released in August 1955; died in 1994 |

| Gustav Adolf Nosske |  |

SS-Obersturmbannführer; member of the Gestapo; commanding officer of Einsatzkommando 12 of Einsatzgruppe D | Life imprisonment | Commuted to 10 years; released in December 1951; died in 1986 |

| Adolf Ott |  |

SS-Obersturmbannführer; member of the SD; commanding officer of Sonderkommando 7b of Einsatzgruppe B | Death by hanging | Commuted to life imprisonment; released on May 9, 1958; died in 1973 |

| Eduard Strauch |  |

SS-Obersturmbannführer; member of the SD; commanding officer of Einsatzkommando 2 of Einsatzgruppe A | Death by hanging; handed over to Belgian authorities and received another death sentence; died prior to execution on 11 September 1955 | |

| Emil Haussmann |  |

SS-Sturmbannführer; member of the SD; officer of Einsatzkommando 12 of Einsatzgruppe D | Committed suicide before the arraignment on July 31, 1947 | |

| Waldemar Klingelhöfer |  |

SS-Sturmbannführer; member of the SD; commanding officer of Vorkommando Moskau of Einsatzgruppe B | Death by hanging | Commuted to life imprisonment; released in December 1956; died in 1977 |

| Lothar Fendler |  |

SS-Sturmbannführer; member of the SD; second highest-ranking officer of Sonderkommando 4b of Einsatzgruppe C | 10 years | Commuted to 8 years; released in March 1951; died in 1983 |

| Waldemar von Radetzky |  |

SS-Sturmbannführer; member of the SD; deputy chief of Sonderkommando 4a of Einsatzgruppe C | 20 years | Released; died in 1990 |

| Felix Rühl |  |

SS-Hauptsturmführer; member of the Gestapo; officer of Sonderkommando 10b of Einsatzgruppe D | 10 years | Released; died in 1982 |

| Heinz Schubert |  |

SS-Obersturmführer; member of the SD; adjutant to Otto Ohlendorf in Einsatzgruppe D | Death by hanging | Commuted to 10 years; released in December 1951; died in 1987 |

| Matthias Graf |  |

SS-Untersturmführer; member of the SD; officer in Einsatzkommando 6 of Einsatzgruppe C | Time served | |

Notes

| ||||

The presiding judge, Michael Musmanno, explained his rationale for sentencing while testifying at the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials in the 1960s. He had chosen to impose death sentences in all cases where the defendant had actively participated in murder and failed to present mitigating circumstances. For example, although Erwin Schulz confessed to presiding over the execution of 90 to 100 men in Ukraine, he received a 20-year sentence since he had protested an order to exterminate all Jewish women and children, and immediately resigned when he was unable to get the order retracted. Superior orders was rejected as a defense.[8]

Of the 14 death sentences, only four were carried out; the others were commuted to prison terms of varying lengths in 1951. In 1958, all convicts were released from prison.

Quotes from the judgment

Summarize

Perspective

The Nuremberg Military Tribunal in its judgement stated the following:

[The facts] are so beyond the experience of normal man and the range of man-made phenomena that only the most complete judicial inquiry, and the most exhaustive trial, could verify and confirm them. Although the principal accusation is murder, ... the charge of purposeful homicide in this case reaches such fantastic proportions and surpasses such credible limits that believability must be bolstered with assurance a hundred times repeated.

... a crime of such unprecedented brutality and of such inconceivable savagery that the mind rebels against its own thought image and the imagination staggers in the contemplation of a human degradation beyond the power of language to adequately portray.

The number of deaths resulting from the activities with which these defendants have been connected and which the prosecution has set at one million is but an abstract number. One cannot grasp the full cumulative terror of murder one million times repeated.

It is only when this grotesque total is broken down into units capable of mental assimilation that one can understand the monstrousness of the things we are in this trial contemplating. One must visualize not one million people but only ten persons – men, women, and children, perhaps all of one family – falling before the executioner's guns. If one million is divided by ten, this scene must happen one hundred thousand times, and as one visualizes the repetitious horror, one begins to understand the meaning of the prosecution's words, "It is with sorrow and with hope that we here disclose the deliberate slaughter of more than a million innocent and defenseless men, women, and children."[5]

See also

- Commissar Order, an order stating that Soviet political commissars were to be shot on the battlefield.

- List of Einsatzgruppen with all known Einsatzgruppen

- Nuremberg executions

Notes

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.