Edward Jenner

English physician and pioneer of vaccines (1749–1823) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Edward Jenner (17 May 1749 – 26 January 1823) was an English physician and scientist who pioneered the concept of vaccines and created the smallpox vaccine, the world's first vaccine.[1][2] The terms vaccine and vaccination are derived from Variolae vaccinae ('pustules of the cow'), the term devised by Jenner to denote cowpox. He used it in 1798 in the title of his Inquiry into the Variolae vaccinae known as the Cow Pox, in which he described the protective effect of cowpox against smallpox.[3]

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Spanish. (March 2025) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Edward Jenner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 17 May 1749 Berkeley, Gloucestershire, England |

| Died | 26 January 1823 (aged 73) Berkeley, Gloucestershire, England |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | |

| Spouse |

Catherine Kingscote

(m. 1788; died 1815) |

| Children | 3 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine/surgery, natural history |

| Academic advisors | John Hunter |

Jenner is often called "the father of immunology",[4] and his work is said to have saved "more lives than any other man".[5]: 100 [6] In Jenner's time, smallpox killed around 10% of the global population, with the number as high as 20% in towns and cities where infection spread more easily.[6] In 1821, he was appointed physician to King George IV, and was also made mayor of Berkeley and justice of the peace. He was a member of the Royal Society. In the field of zoology, he was among the first modern scholars to describe the brood parasitism of the cuckoo (Aristotle also noted this behaviour in his History of Animals). In 2002, Jenner was named in the BBC's list of the 100 Greatest Britons.

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Edward Jenner was born on 17 May 1749[7] in Berkeley, Gloucestershire, England as the eighth of nine children.[8] His father, the Reverend Stephen Jenner, was the vicar of Berkeley, so Jenner received a strong basic education.[7]

Education and training

When he was young, he went to school in Wotton-under-Edge at Katherine Lady Berkeley's School and in Cirencester.[7] During this time, he was inoculated (by variolation) for smallpox, which had a lifelong effect upon his general health.[7] At the age of 14, he was apprenticed for seven years to Daniel Ludlow, a surgeon of Chipping Sodbury, South Gloucestershire, where he gained most of the experience needed to become a surgeon himself.[7]

In 1770, aged 21, Jenner became apprenticed in surgery and anatomy under surgeon John Hunter and others at St George's Hospital, London.[9] William Osler records that Hunter gave Jenner William Harvey's advice, well known in medical circles (and characteristic of the Age of Enlightenment), "Don't think; try."[10] Hunter remained in correspondence with Jenner over natural history and proposed him for the Royal Society. Returning to his native countryside by 1773, Jenner became a successful family doctor and surgeon, practising on dedicated premises at Berkeley. In 1792, "with twenty years' experience of general practice and surgery, Jenner obtained the degree of MD from the University of St Andrews".[2]

Later life

Jenner and others formed the Fleece Medical Society or Gloucestershire Medical Society, so called because it met in the parlour of the Fleece Inn, Rodborough, Gloucestershire. Members dined together and read papers on medical subjects. Jenner contributed papers on angina pectoris, ophthalmia, and cardiac valvular disease and commented on cowpox. He also belonged to a similar society which met in Alveston, near Bristol.[11]

He became a master mason on 30 December 1802, in Lodge of Faith and Friendship #449. From 1812 to 1813, he served as worshipful master of Royal Berkeley Lodge of Faith and Friendship.[12]

Zoology

Summarize

Perspective

Jenner was elected fellow of the Royal Society in 1788, following his publication of a careful study of the previously misunderstood life of the nested cuckoo, a study that combined observation, experiment, and dissection.

Jenner described how the newly hatched cuckoo pushed its host's eggs and fledgling chicks out of the nest (contrary to existing belief that the adult cuckoo did it).[13] Having observed this behaviour, Jenner demonstrated an anatomical adaptation for it – the baby cuckoo has a depression in its back, not present after 12 days of life, that enables it to cup eggs and other chicks. The adult does not remain long enough in the area to perform this task. Jenner's findings were published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1788.[14][15]

"The singularity of its shape is well adapted to these purposes; for, different from other newly hatched birds, its back from the scapula downwards is very broad, with a considerable depression in the middle. This depression seems formed by nature for the design of giving a more secure lodgement to the egg of the Hedge-sparrow, or its young one, when the young Cuckoo is employed in removing either of them from the nest. When it is about twelve days old, this cavity is quite filled up, and then the back assumes the shape of nestling birds in general."[16] Jenner's nephew assisted in the study. He was born on 30 June 1737.

Jenner's understanding of the cuckoo's behaviour was not entirely believed until the artist Jemima Blackburn, a keen observer of birdlife, saw a blind nestling pushing out a host's egg. Blackburn's description and illustration were enough to convince Charles Darwin to revise a later edition of On the Origin of Species.[17]

Jenner's interest in zoology played a large role in his first experiment with inoculation. Not only did he have a profound understanding of human anatomy due to his medical training, but he also understood animal biology and its role in human-animal trans-species boundaries in disease transmission. At the time, there was no way of knowing how important this connection would be to the history and discovery of vaccinations. We see this connection now; many present-day vaccinations include animal parts from cows, rabbits, and chicken eggs, which can be attributed to the work of Jenner and his cowpox/smallpox vaccination.[18]

Marriage and human medicine

Jenner married Catherine Kingscote (who died in 1815 from tuberculosis) in March 1788. He might have met her while he and other fellows were experimenting with balloons. Jenner's trial balloon descended into Kingscote Park, Gloucestershire, owned by Catherine's father Anthony Kingscote.[19] They had three children: Edward Robert (1789–1810), Robert Fitzharding (1792–1854) and Catherine (1794–1833).[8]

He earned his MD from the University of St Andrews in 1792.[20] He is credited with advancing the understanding of angina pectoris.[21] In his correspondence with Heberden, he wrote: "How much the heart must suffer from the coronary arteries not being able to perform their functions".[22]

Invention of the vaccine

Summarize

Perspective

Inoculation was already a standard practice in Asian and African medicine but involved serious risks, including the possibility that those inoculated would become contagious and spread the disease to others.[23] In 1721, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu had imported variolation to Britain after having observed it in Constantinople. While Johnnie Notions had great success with his self-devised inoculation[24] (and was reputed not to have lost a single patient),[25] his method's practice was limited to the Shetland Islands. Voltaire wrote that at this time 60% of the population caught smallpox and 20% of the population died from it.[26] He also stated that the Circassians used the inoculation from times immemorial, and that the Turks may have borrowed the custom from them.[27] In 1766, Daniel Bernoulli analysed smallpox morbidity and mortality data to demonstrate the efficacy of inoculation.[28]

By 1768, English physician John Fewster had realised that prior infection with cowpox rendered a person immune to smallpox.[29][30] In the years following 1770, at least five investigators in England and Germany (Sevel, Jensen, Jesty 1774, Rendell, Plett 1791) successfully tested a cowpox vaccine against smallpox in humans.[31] For example, Dorset farmer Benjamin Jesty[32] successfully vaccinated with cowpox and presumably induced immunity in his wife and two children during the 1774 smallpox epidemic, though it was not until Jenner's work that the procedure became widely understood. Jenner may have been aware of Jesty's procedures and success.[33] In 1780, Jacques Antoine Rabaut-Pommier made similar observations in France.[34]

Jenner postulated that the pus in blisters from sufferers of cowpox (a disease similar to smallpox but much less virulent) protected them from smallpox. On 14 May 1796, Jenner tested his hypothesis by inoculating James Phipps, the eight-year-old son of Jenner's gardener. He scraped pus from cowpox blisters on the hands of Sarah Nelmes, a milkmaid who had caught cowpox from a cow called Blossom[35] (whose hide now hangs on the wall of the St. George's Medical School library, now in Tooting, London). Phipps was the 17th case described in Jenner's first paper on vaccination.[36]

Jenner inoculated Phipps in both arms that day; this led to a fever and some uneasiness but no full-blown infection. Later, Jenner injected Phipps with variolous material, the routine method of immunization at that time and again no disease followed. The boy was later challenged with variolous material and again showed no sign of infection. There were no unexpected side effects, and neither Phipps nor any other recipients underwent any future 'breakthrough' cases.

Jenner's biographer John Baron later speculated that it was Jenner's observation of the unblemished complexion of milkmaids that led to his understanding that it was possible to be inoculated against smallpox by being exposed to cowpox, that is he did not build on the work of his predecessors. The milkmaid story is still widely repeated even though it appears to be a myth.[37][38]

US physician Donald Hopkins has written, "Jenner's unique contribution was not that he inoculated a few persons with cowpox, but that he then proved [by subsequent challenges] that they were immune to smallpox. Moreover, he demonstrated that the protective cowpox pus could be effectively inoculated from person to person, not just directly from cattle."[39] Jenner successfully tested his hypothesis on 23 additional subjects.

Jenner continued his research and reported it to the Royal Society, though the initial paper was not published. After revisions and further investigations, he published his findings on the 23 cases, including his 11-month-old son Robert.[40] Some of his conclusions were correct, some erroneous; modern microbiological and microscopic methods would make his studies easier to reproduce. The medical establishment deliberated at length over his findings before accepting them. Eventually, vaccination was accepted, and in 1840, the British government banned variolation – the use of smallpox to induce immunity – and provided vaccination using cowpox free of charge (see Vaccination Act).

The success of Jenner's discovery soon spread around Europe and was used en masse in the Spanish Balmis Expedition (1803–1806), a three-year-long mission to the Americas, the Philippines, Macao and China led by Francisco Javier de Balmis with the aim of giving the smallpox vaccine to thousands.[41] The expedition was successful, and Jenner wrote: "I don't imagine the annals of history furnish an example of philanthropy so noble, so extensive as this".[42] Napoleon, who at the time was at war with Britain, had all his French troops vaccinated, awarded Jenner a medal, and at Jenner's request, released two English prisoners of war, allowing them to their return home.[43][44] Napoleon remarked he could not "refuse anything to one of the greatest benefactors of mankind".[43]

Jenner's continuing work on vaccination prevented him from continuing his ordinary medical practice. He was supported by his colleagues and King George III in petitioning Parliament,[45] and in 1802 was granted £10,000 for his work on vaccination.[46] In 1807, he was granted another £20,000 after the Royal College of Physicians confirmed the widespread efficacy of vaccination.[2]

- Edward Jenner advising a farmer to vaccinate his family. Oil painting by an English painter, c. 1910

- Jenner's discovery of the link between cowpox pus and smallpox in humans helped him to create the smallpox vaccine.

- Jenner performing his first vaccination on James Phipps, a boy of age 8, on 14 May 1796

- James Gillray's 1802 caricature of Jenner vaccinating patients who feared it would make them sprout cowlike appendages.

- 1808 cartoon showing Jenner, Thomas Dimsdale and George Rose seeing off anti-vaccination opponents

- 1873 sculpture of Jenner Vaccinating His Own Son Against Smallpox by Italian sculptor Giulio Monteverde, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, Rome

Later life

Summarize

Perspective

Jenner was later elected a foreign honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1802, a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1804,[47] and a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1806.[48] In 1803 in London, he became president of the Jennerian Society, concerned with promoting vaccination to eradicate smallpox. The Jennerian ceased operations in 1809. Jenner became a member of the Medical and Chirurgical Society on its founding in 1805 (now the Royal Society of Medicine) and presented several papers there. In 1808, with government aid, the National Vaccine Establishment was founded, but Jenner felt dishonoured by the men selected to run it and resigned his directorship.[5]: 122–125

Returning to London in 1811, Jenner observed a significant number of cases of smallpox after vaccination. He found that in these cases the severity of the illness was notably diminished by previous vaccination. In 1821, he was appointed physician extraordinary to King George IV, and was also made mayor of Berkeley[2] and magistrate[5]: 303 (justice of the peace). He continued to investigate natural history, and in 1823, the last year of his life, he presented his "Observations on the Migration of Birds" to the Royal Society.[46]

Death

Jenner was found in a state of apoplexy on 25 January 1823, with his right side paralysed.[5]: 314 He did not recover and died the next day of an apparent stroke, his second, on 26 January 1823,[5] aged 73. He was buried in the family vault at the Church of St Mary, Berkeley.[51]

Religious views

Neither fanatic nor lax,[52] Jenner was a Christian who in his personal correspondence showed himself quite spiritual.[5]: 141 Some days before his death, he stated to a friend: "I am not surprised that men are not grateful to me; but I wonder that they are not grateful to God for the good which He has made me the instrument of conveying to my fellow creatures".[5]: 295

Legacy

In 1980, the World Health Organization declared smallpox an eradicated disease.[53] This was the result of coordinated public health efforts, but vaccination was an essential component. Although the disease was declared eradicated, some pus samples still remain in laboratories in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta in the US, and in State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR in Koltsovo, Novosibirsk Oblast, Russia.[54]

Jenner's vaccine laid the foundation for contemporary discoveries in immunology.[55] In 2002, Jenner was named in the BBC's list of the 100 Greatest Britons following a UK-wide vote.[56] Commemorated on postage stamps issued by the Royal Mail, in 1999 he featured in their World Changers issue along with Charles Darwin, Michael Faraday and Alan Turing.[57] The lunar crater Jenner is named in his honour.[58]

Monuments and buildings

- Jenner's house in the village of Berkeley, Gloucestershire, is now a small museum,[2] housing, among other things, the horns of the cow, Blossom.

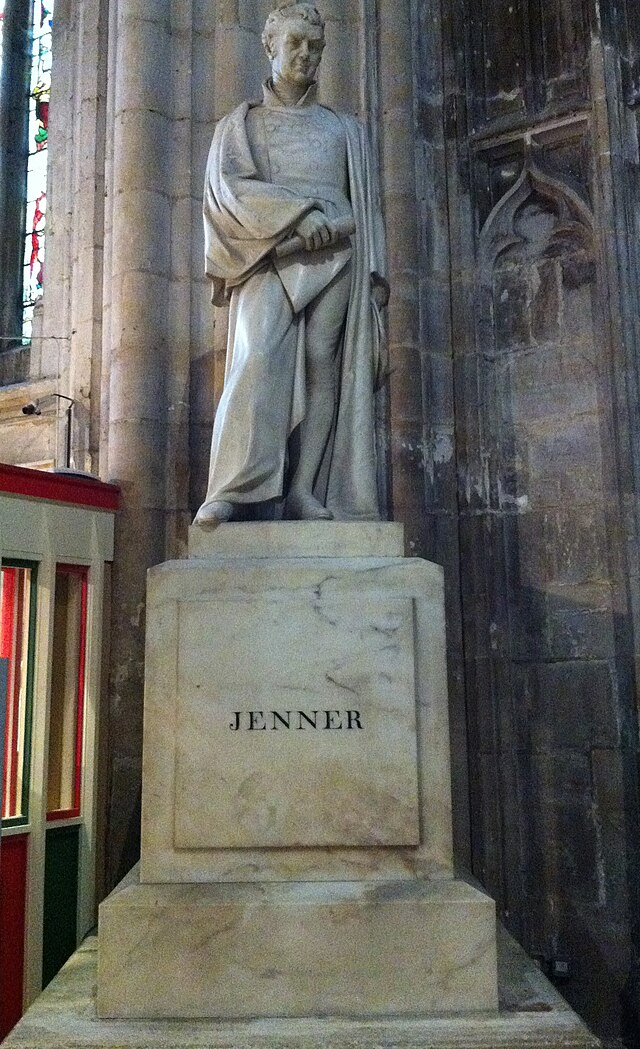

- A statue of Jenner by Robert William Sievier was erected in the nave of Gloucester Cathedral.[59]

- Another statue was erected in Trafalgar Square and later moved to Kensington Gardens.[60]

- Near the Gloucestershire village of Uley, Downham Hill is locally known as "Smallpox Hill" for its possible role in Jenner's studies of the disease.[61]

- London's St. George's Hospital Medical School has a Jenner Pavilion, where his bust may be found.[62]

- A group of villages in Somerset County, Pennsylvania, United States, was named in Jenner's honour by early 19th-century English settlers, including Jenners, Jenner Township, Jenner Crossroads, and Jennerstown, Pennsylvania.[63]

- Jennersville, Pennsylvania, is located in Chester County.[64]

- The Edward Jenner Institute for Vaccine Research is an infectious disease vaccine research centre, also the Jenner Institute part of the University of Oxford.

- A section at Gloucestershire Royal Hospital is known as the Edward Jenner Unit; it is where blood is drawn.[65]

- A ward at Northwick Park Hospital is called Jenner Ward.[66]

- Jenner Gardens at Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, opposite one of the scientist's former offices, is a small garden and cemetery.[67]

- A statue of Jenner was erected at the Tokyo National Museum in 1896 to commemorate the centenary of Jenner's discovery of vaccination.[68]

- A monument outside the walls of the upper town of Boulogne sur Mer, France.[69]

- A street in Stoke Newington, north London: Jenner Road, N16 51.55867°N 0.06761°W

- Built around 1970, The Jenner Health Centre, 201 Stanstead Road, Forest Hill, London, SE23 1HU[70]

- Jenner's name is featured on the Frieze of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Twenty-three names of public health and tropical medicine pioneers were chosen to feature on the Keppel Street building when it was constructed in 1926.[71]

- Minor planet 5168 Jenner is named in his honour.[72]

- Jenner's House, The Chantry, Church Lane, Berkeley, Gloucestershire, England

- Bronze statue of Jenner in Kensington Gardens, London

- Edward Jenner's name as it appears on the Frieze of the LSHTM Keppel Street building

Publications

- 1798 An Inquiry Into the Causes and Effects of the Variolæ Vaccinæ

- 1799 Further Observations on the Variolæ Vaccinæ, or Cow-Pox[73]

- 1800 A Continuation of Facts and Observations relative to the Variolæ Vaccinæ 40pp.[74]

- 1801 The Origin of the Vaccine Inoculation[75]

See also

- History of science

- Koyama Shisei, Japanese vaccinologist (1807–1862) who improved upon the Jennerian smallpox vaccine

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.