Loading AI tools

Australian journalist From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

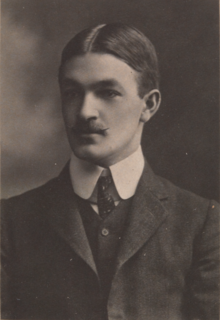

Edward George Honey (18 September 1885 – 25 August 1922) was an Australian journalist who suggested the idea of five minutes of silence in a letter to a London newspaper in May 1919, about 6 months before the first observance of the Two-minute silence in London.

Edward George Honey | |

|---|---|

E.G. Honey, of The Argus, c.1908 | |

| Born | 18 September 1885 |

| Died | 25 August 1922 (aged 36) Northwood, London, England |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Spouse |

Amelia Josephine Honey, née Toomey

(m. 1915) |

The Australian government officially credits him with being the originator of this tradition, observed on Armistice Day (now known as Remembrance Day), but no original sources from that time have been found to confirm this, and most non-Australian sources attribute its origin to Sir Percy FitzPatrick. It is not known whether Honey was aware of the practice started in Cape Town on 14 May 1918, nearly a year earlier.

The son of Edward Honey, and Mary Honey, née Bolton, Edward George Honey was born at Elsternwick, Melbourne, on 18 September 1885.[1] Edward Senior ran an indenting agency at 31 Queen Street, Melbourne.[2] His only brother, William Henry Honey (1879–1959) was an author and publisher (W.H. Honey Publishing Co., Margaret-street, Sydney), who also worked in advertising.[3] One of his three sisters, was the talented and successful artist Constance Winifred Honey[2] who moved to London after being awarded the (Melbourne) National Gallery's Travelling Scholarship, had works hung in the National Gallery annual exhibitions, never returned to Australia and later died in an accident in London in 1944.[4][Note 1]

Honey married Amelia Josephine "Millie" Toomey (1885–1969), the daughter of Thomas Toomey and Helena Toomey, née Mee, in England on 24 June 1915.[5][6][7][8]

As was the case with his older brother William,[9][10] Honey was educated at Caulfield Grammar School, in St Kilda East,[11] and he attended from 1895, when he was 10 years old.[12][13][14][Note 2]

He completed his education at Wellington College, in Mount Victoria, New Zealand.[15]

IN THE STREET.

Words we let fall in the street,

When dusk is falling around,

Lost midst the clattering feet,

Die in the great roar of sound.

Smiles we exchange as we pass—

Of friendship, hate, or disdain,

As varies Society's glass;—

We smile and vanish again.

Remembrance remains—will remain;

Stings the hurt feelings and heart;

Yet when we meet once again,

We'll smile, we'll pass—far apart.

—E. G. Honey, Dunedin, June, 1902.[16]

In early 1904, at the age of 18, Honey became part owner of a small magazine called Spectre in Palmerston North,[17] New Zealand which went bankrupt. He then worked as journalist for a paper which folded. He returned to Australia and worked for his father trying to attract new clients in Queensland, without success. He returned to Melbourne to work for The Argus newspaper for a while.[18]

In 1909 he moved to London and worked for the Daily Mail. He suffered from poor health and, after many weeks in hospital was sent by Lord Northcliffe, owner of the newspaper, to recuperate at a hydro in Warwickshire. Before going there, however, Honey went to the races at Epsom the next day, where he was spotted by other journalists, and upon his return to London found his pay cheque and dismissal notice ready for him.[14]

Honey was employed on staff at the Daily Citizen, a newspaper launched in 1912 by the Labour Party. The Daily Citizen folded in 1915.[19] He appeared as a visitor staying at a hotel in Bourton-on-the-Water in the Cotswolds in the 1911 Census, aged 26 and occupation shown as "author journalist".[20]

He apparently missed an opportunity for an assignment as a war correspondent in late 1914 working for one of London's leading editors, when his wife could not find him in all of "his usual haunts in Fleet Street".[14]

On discharge from the military, Honey returned to Fleet Street as a freelance journalist. His work was widely published including in; the Daily Mail, the Evening News, The Daily Sketch, The Chronicle and the Daily Mirror. Honey used multiple nom de plumes for his freelance articles e.g. Warren Foster, Margaret Graham and Joan Sinclair.

In 1919 his biography of the Minister of Food Control, and future leader of the Labour Party, From mill boy to minister : an intimate account of the life of Rt. Honourable J.R. Clynes, M.P, was published by J M Dent.[21] Honey published the biography using the pen name Edward George.

He enlisted in the Middlesex Regiment on 16 April 1915 as a clerk. He was not sent abroad and was discharged on 17 April 1916 under para 392, XXV (Services no longer required).[22][23][14]

On 8 May 1919 a letter Honey wrote to Evening News newspaper, was published under the headline "A Peace Day Essential."[24] Honey used the pen name Warren Foster.[25] He suggested silence was an appropriate commemoration for the first anniversary of the Armistice which signalled the end of World War I, on 11 November 1918: the "eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month".[26]

In "A Peace Day Essential" Honey said,

Honey had been prompted to make the suggestion as he had been angered by the way in which people had celebrated with dancing in the streets on the day of the Armistice, and believed a period of silence to be a far more appropriate gesture in memory of those who had died at war.[14] He also drew upon the experience he had in a train travelling in the west of England during a silent interlude for the funeral of King Edward VII. All trains and traffic stopped at noon on the day. Five people in his train compartment "sat uncovered" for 3 minutes.[2][28]

There is no record of Honey's letter having officially inspired the Remembrance Day tradition. However, his wife Millie said that journalists in Fleet Street believed Honey was the instigator of the silence[29][30] Nearly 7 months after Honey's letter, records close to King George V show that on 27 October 1919, a suggestion from South African author and politician Sir Percy Fitzpatrick for a similar idea for a moment of silence was forwarded to George V, then King of the United Kingdom. The letter was sent though Lord Milner, who had previously held high office in South Africa, On 7 November 1919, King George V formally requested the observance of the two minutes' silence throughout the British Empire.[31][32]

Honey died on 25 August 1922 at the age of 36, whilst a patient at the Mount Vernon Hospital.[33] He was buried in 'Section B' at Northwood Cemetery in North West London.[34] A small brass plaque commemorates his life and role in the two minutes silence.[35]

In 1937, his widow reported to a journalist that she had been left penniless after her husband's death.[36][37]

A monument to Honey was erected by Eric Harding near the Shrine of Remembrance in St Kilda Road in 1965.[38][39][40] It was unveiled by the Lord Mayor of Melbourne, Leo Curtis on 7 May 1965.[41]

Although the Australian government officially recognises Honey as having first raised the idea in the public domain,[42][43] George V officially thanked Fitzpatrick for his contribution of the Two Minute Pause in 1920.[44]

A letter to an Australian newspaper in 1925 suggests that Honey may have been inspired by silences observed in the United States when the Maine was finally sunk in 1912.[33]

The contribution of Honey was recognised by the then-principal of Caulfield Grammar School, Walter Murray Buntine,[45] in the school's 1931 golden jubilee publication:[46]

Eric Harding's booklet written in support of the monument to Honey erected in 1965 acknowledges that other silences had been held before (upon the death of King Edward, the silences in South Africa "when the war was going badly for the Allies", ceremonies in Australia for lost miners, in the US when the Maine was sunk, amongst others), but in his words "the originality of Honey's suggestion is based on the fact that this was the first time in history that a victory had been celebrated as a tribute to those who sacrificed their lives and their health to make the victory possible".[Note 3] Harding also acknowledges that, despite extensive research, no evidence of Honey's attendance at any rehearsal at Buckingham Palace, nor any record of an official communication mentioning Honey's letter having played a part in the adoption of the remembrance tradition, could be found, and that the only "proof" was that the letter preceded the formal approach to the King by several months. However he also writes that "Sir Percy's right to recognition for bringing the matter to official notice does not detract in any way from Honey's right to recognition as the first to make the suggestion."[2]

According to an Australian War Memorial article, Honey attended a trial of the event with the Grenadier guards at Buckingham Palace, as did Fitzpatrick (although it was not known whether they ever actually met or discussed their ideas).[48] However, Honey's wife (whom he called "Millie"), as reported by her friend M.F. Orford's 1961 article, states that he "never went out into the streets near the crowds at any time during the observance of the Silence...”, and they only heard about the observance of the first Two Minutes' Silence when the order was announced by Buckingham Palace.[14]

An unidentified Age reporter describes a visit to the Shrine of Remembrance in 2005 and being told by the Senior Custodian, Tony Bowers,[49] as recorded in an article written by a Shrine researcher, that the Silence had not in fact been invented by Honey, but by Fitzpatrick based on the Cape Town Mayor's practice.[50]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.