Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Totenkopf

German symbol for skull and crossbones From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Totenkopf (German: [ˈtoːtn̩ˌkɔpf], i.e. skull, literally "dead person's head") is the German word for skull. The word is often used to denote a figurative, graphic or sculptural symbol, common in Western culture, consisting of the representation of a human skull – usually frontal, more rarely in profile with or without the mandible. In some cases, other human skeletal parts may be added, often including two crossed long bones (femurs) depicted below or behind the skull (when it may be referred to in English as a "skull and crossbones"). The human skull is an internationally used symbol for death, the defiance of death, danger, or the dead, as well as piracy or toxicity.

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (June 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

In English, the term Totenkopf is commonly associated with 19th- and 20th-century German military use, particularly in Nazi Germany.

The german word for skull without emotional connotation is Schädel.

Remove ads

Naval use

In early modern sea warfare to early modern sea piracy, buccaneers and pirates used the Totenkopf as a pirate flag: a skull or other skeletal parts as a death threat and as a demand to hand over a ship. The symbol continues to be used by modern navies.

- Emanuel Wynne's flag flown in 1700[1]

- Bartholomew Roberts' flag as described in a report from 1720[2]

- John Taylor, Edward England and Samuel Bellamy's flag as described by eyewitness Thomas Baker (Bellamy's crew)[3]

- Stede Bonnet's flag as described in a report from the 1718 Boston News-Letter[4]

- 19th century Jolly Roger used by Barbary corsairs

- Insignia for the USMC Marine Raiders

Remove ads

German military

Summarize

Perspective

Prussia

Use of the Totenkopf in Germany as a military emblem began under Frederick the Great, who formed a regiment of Hussar cavalry in the Prussian army commanded by Colonel von Ruesch, the Husaren-Regiment Nr. 5 (von Ruesch). It adopted a black uniform with a Totenkopf emblazoned on the front of its mirlitons and wore it on the field in the War of Austrian Succession and in the Seven Years' War.[5] The Totenkopf remained a part of the uniform when the regiment was reformed into Leib-Husaren Regiments Nr.1 and Nr.2 in 1808.[6] The symbol was then granted 3 years later to the Spanish Army’s 8th Light Cavalry Regiment “Lusitania”, who were nicknamed “Los Dragones de la Muerte” (the Dragons of Death) and were granted use of the skull after the infamous Battle of Madonna dell'Olmo in 1744, where they suffered great casualties.

Brunswick

In 1809, during the War of the Fifth Coalition, Frederick William, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel raised a force of volunteers to fight Napoleon Bonaparte, who had conquered the Duke's lands. The Brunswick corps was provided with black uniforms, giving rise to their nickname, the Black Brunswickers. Both hussar cavalry and infantry in the force wore a Totenkopf badge, either in mourning for the duke's father, Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, who had been killed at the Battle of Jena–Auerstedt in 1806, or according to some sources, as a sign of revenge against the French. After fighting their way through Germany, the Black Brunswickers entered British service and fought with them in the Peninsular War and at the Battle of Waterloo. The Brunswick corps was eventually incorporated into the Prussian Army in 1866.[7]

German Empire

The skull continued to be used by the Prussian and Brunswick armed forces until 1918, and some of the stormtroopers that led the last German offensives on the Western Front in 1918 used skull badges.[8] Luftstreitkräfte fighter pilots Georg von Hantelmann[9] and Kurt Adolf Monnington[10] are just two of a number of Central Powers military pilots who used the Totenkopf as their personal aircraft insignia.

Weimar Republic

The Totenkopf was used in Germany throughout the interwar period, most prominently by the Freikorps. In 1933, it was in use by the regimental staff and the 1st, 5th, and 11th squadrons of the Reichswehr's 5th Cavalry Regiment as a continuation of a tradition from the Kaiserreich.[citation needed]

- Flag of the Iron Division Freikorps

- Armed Freikorps troops in Berlin in 1919

- A Garford-Putilov Armoured Car used by the Freikorps in 1919

- Flag at a meeting of former Brüssow Freikorps members in 1934

Nazi Germany

In the early days of the Nazi Party, Julius Schreck, the leader of the Stabswache (Adolf Hitler's bodyguard unit), resurrected the use of the Totenkopf as the unit's insignia. This unit grew into the Schutzstaffel (SS), which continued to use the Totenkopf as insignia throughout its history. According to a writing by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, the Totenkopf had the following meaning:

The Skull is the reminder that you shall always be willing to put your self at stake for the life of the whole community.[11]

SS-Totenkopfverbände ('Death's Head Units') was the Schutzstaffel (SS) organization responsible for administering the Nazi concentration camps and extermination camps for Nazi Germany, among similar duties. While the Totenkopf was the universal cap badge of the SS, the SS-TV also wore this insignia on the right collar tab to distinguish itself from other SS formations.

The Totenkopf was also used as the unit insignia of the Panzer forces of the German Heer (Army), and also by the Panzer units of the Luftwaffe, including those of the elite Fallschirm-Panzer Division 1 Hermann Göring.[12]

Both the 3rd SS Panzer Division of the Waffen-SS, and the World War II era Luftwaffe's 54th Bomber Wing Kampfgeschwader 54 were given the unit name "Totenkopf", and used a strikingly similar-looking graphic skull-crossbones insignia as the SS units of the same name. The 3rd SS Panzer Division also had skull patches on their uniform collars instead of the SS sieg rune.[citation needed]

- The first version of the SS-Totenkopf; used from 1923 to 1934

- The second version of the SS-Totenkopf; used from 1934 to 1945

- Junkers Ju 88 of Kampfgeschwader 54 (KG 54) in France, November 1940

- The "standalone" version of the WW II Luftwaffe KG 54 wing's dead's head unit insignia

- German Panzer totenkopf

- German SS uniform. Peaked visor cap with skull emblem (Totenkopf)

- Members of SS Handschar; the SS-Totenkopf was printed on their fez cap.

Remove ads

Non-German military

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2019) |

- A skull and crossbones has often been a symbol of pirates, especially in the form of the Jolly Roger, but usually having the crossbones below the skull's lower mandibile (if present) rather than behind it, as used by pirate Samuel Bellamy in one example.

- The second oldest usage in a military uniform was that of the Spanish Army's Lusitania Dragoon Regiment, which adopted it in 1744. It included three skull and crossbones in the cuffs,[14] and in 1902 the skull and crossbones insignia was authorized again to replace the regiment number on the sides of the collar.[15]

- It was used as the emblem on the uniforms of Greek revolutionaries of Alexander Ypsilantis' Sacred Band (1821) during the Wallachian uprising of 1821

- Armenian fedayis, during the First World War against the Ottoman Empire, used a skull with two bolt rifles under the words "revenge revenge" in their flags.

- The British Army's Royal Lancers continue to use the skull and crossbones in their emblem, inherited from its use by the 17th Lancers, a unit raised in 1759 following General Wolfe's death in Quebec. The emblem contains an image of a death's head, and the words 'Or Glory', chosen in commemoration of Wolfe.[16]

- In 1792, a regiment of Hussards de la Mort (Death Hussars) was formed during the French Revolution by the French National Assembly and were organized and named by Kellerman. The group of 200 volunteers were from wealthy families and their horses were supplied from the King's Stables. They were formed to defend against various other European states in the wake of the revolution. They participated in the Battle of Valmy and its members also participated in the Battle of Fleurus (1794). They had the following mottos: Vaincre ou mourir, La liberté ou la mort and Vivre libre ou mourir – Victory or death; Freedom or death; and Live free or die.[17][18][19]

- Although not exactly a Totenkopf per se, the Chilean guerrilla leader Manuel Rodríguez used the symbol on his elite forces called Husares de la muerte ("Hussars of death"). It is still used by the Chilean Army's 3rd Cavalry Regiment.

- The primarily Prussian 41st Regiment New York Volunteer Infantry (mustered on 6 June 1861; mustered out 9 December 1865) wore a skull insignia.[20]

- The Vengeurs de la Mort ("death avengers"), an irregular unit of Commune de Paris, 1871.[21]

- The Portuguese Army Police 2nd Lancers Regiment use a skull-and-crossbones image in their emblem, similar to the one used by the Queen's Royal Lancers.

- The Kingdom of Sweden's Hussar Regiments wore a death's head emblem in the Prussian Style on the front of the mirleton.

- Ramón Cabrera's regiment adopted in 1838 a skull with crossbones flanked by an olive branch and a sword on a black flag during the Spanish Carlist Wars.

- Serbian Chetniks wore a death's head emblem in several conflicts: guerrilla in Old Serbia, First and Second Balkan Wars, World War I (both defense and resistance) and World War II.

- Some Macedonian-Bulgarian komitas that were members of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization wore a death's head emblem, usually with crossed revolver and qama below the skull and crossbones (similar to the Serbian ones) throughout the existence of the organization in several conflicts: Macedonian Struggle (Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising, the Balkan Wars), World War I, during the interwar period in Macedonia, Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, and in World War II. The most prominent example being Pitu Guli who wears one in his only known photo, and his son Steryu Gulev.

- The Italian elite storm-troopers of the Arditi used a skull with a dagger between its teeth as a symbol during World War I. Various versions of skulls were also later used by the Italian Fascists.[citation needed]

- The Russian Kornilov's Shock Detachment (8th Army) adopted a death's head emblem in 1917. Then after World War I, the unit became Kornilov's Shock Regiment as a part of the White Russian Volunteer Army during the Russian Civil War. Also a death's head emblem was depicted on 17th Don Cossack regiment and Mariupol 4th Hussar regiment badges of Russian Imperial Army.

- The Estonian Kuperjanov's Partisan Battalion used the skull-and-crossbones as their insignia (since 1918); the Kuperjanov Infantry Battalion continues to use the skull and crossbones as their insignia today.

- Two Polish small cavalry units used death's head emblem during Polish–Ukrainian War and Polish–Soviet War – Dywizjon Jazdy Ochotniczej (also known as Huzarzy Śmierci i.e. Death Hussars) and Poznański Ochotniczy Batalion Śmierci.

- During 1943–1945 the Italian Black Brigades and numerous other forces fighting for the Italian Social Republic wore various versions of skulls on their uniforms, berets, and caps.

- The United States Marine Corps Reconnaissance Battalions use the skull-and-crossbones symbol in their emblem.[22]

- The No. 100 Squadron RAF (Royal Air Force) continue to use a flag depicting a skull and crossbones,[22] supposedly in reference to a flag stolen from a French brothel in 1918.[citation needed]

- The Batalhão de Operações Policiais Especiais, a special unit within the military police of Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil, uses the skull emblem to differentiate their team from the regular units.

- South Korea's 3rd Infantry Division (백골부대) have a skull-and-crossbones in their emblem.[22]

- Many United States Cavalry reconnaissance troops or squadrons utilize a skull insignia, often wearing the traditional Stetson hat, and backed by either crossed cavalry sabers, crossed rifles, or some other variation, as an unofficial unit logo. These logos are incorporated into troop T-shirts, challenge coins, or other items designed to enhance morale and esprit de corps.

- A version of the Punisher skull symbol has been used by U.S. military personnel since the Iraq War.

- Members of the Azov Regiment of the Ukrainian National Guard have used the totenkopf.[23]

- 72nd Mechanized Brigade of Ukrainian Ground Forces have a skull in their emblem.

- The skull and crosshair were the main symbol of the Wagner Group until it was merged with the Rosgvardiya.

Gallery

Flags

- Flag used from 1811 to 1812 by Regimiento de la muerte (Death Regiment) after Hidalgo's death in the Independence War

- One of the flags used by Argentine caudillo Facundo Quiroga, "Rn.o M." means "Religion or Death" (1825-1834)

- Spanish Carlist flag (1838)

- Flag used by Filipino revolutionary general Mariano Llanera (1896–1899)

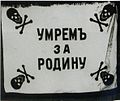

- Banner of one of Russian "Death Units", formed in Eastern Front in 1917

- Sailors of the Petropavlovsk in Helsinki, before the Finnish Civil War (Summer 1917); Flag calls for "death to the bourgeoisie", the flag was later used during the Kronstadt uprising and the occupation of Naissaar Island.

- Kornilov's Shock Detachment flag bearer and honor guard (1917)

- Polish Voluntary II Death Squad in Lviv, Ukraine (1920)

- Flag used by Svyryd Kotsur's Dnipro Division, with the slogan "Death to all who stand in the way of freedom for the working people" (1920)[24]

- Reconstruction of the insignia used by the Arditi del Popolo (1921–1924)

- A flag captured by U.S. marines from Sandino's forces in 1932

Other

- A French Hussard de la mort (1792)

- Alexander Ypsilantis, founder of the military force The Sacred Band, shown wearing the fighting force's uniform, complete with mandible-less totenkopf (1821)

- Cap badge of the British 17th Lancers

- Swedish hussars in 1761

- Pin worn by veterans of the Battle of Lwów. The G.S. stands for Góra Stracenia (Execution Mount) (1918).

- The "death's head" was the insignia of Polish Death Hussar Divisions, 1920 (Polish–Soviet War).

- Early symbol of the Fire Cross League

- Helmet of a Finnish Light detachment 4 (World War II) in skeletal paint scheme

- Insignia of the Estonian Kuperjanov Infantry Battalion

- Stylized Totenkopf on shoulder sleeve insignia of the United States Air Force 400th Missile Squadron uniform sometime between 1995 and 2005

- United States Army's 24th Infantry Regiment's "Deuce four skull" symbol used to mark buildings where enemy combatants had been killed in Iraq as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom (2004)

- Totenkopf inspired patch depicting Punisher (Marvel character) skull symbol, without optional leg bones, worn by US Navy SEALs (2012)

- Insignia of the Syrian Republican Guard (2021)

- Emblem of the Polish Volunteer Corps

Remove ads

Police use

- The uniform of the Ordnungspolizei -- Nazi Germany's uniformed police could feature the totenkopf. Peaked visor cap of the Sicherheitsdienst SD with skull emblem.

- "Punisher" variations of the totenkopf appear on police vehicles.[25]

- Challenge coins as used by the Firearms Training Team for the Calgary, Canada police force.[26]

- Peaked visor cap of the Sicherheitsdienst SD with skull emblem. Norwegian Armed Forces Museum, Oslo, Norway (1936).

- Armored personnel carrier used by the Batalhão de Operações Policiais Especiais (BOPE). The BOPE website states the logo represents victory over death[27] (2018).

- Challenge coin used by the Firearms Training branch of the Calgary Police Service (2020).[28]

Remove ads

Other uses

- International hazard symbol to indicate poisonous substances

- Craft International logo, military training company founded by Chris Kyle

- Wilhelm "Deathshead" Strasse, a major antagonist in the Wolfenstein series, is named after the symbol

- Sometimes placed within a circle next to a 6 to represent Death in June

- The phrase "never lose your smile" is sometimes used in social media posts as a way of subtly expressing Nazi sympathies, particularly in countries where open promotion of Nazism is illegal. The phrase refers to the totenkopf skull, which, in some versions of the symbol, appears to be smiling. As the phrase also has innocuous meanings, its use by neo-Nazis is an example of a dogwhistle that relies on plausible deniability.[29]

Remove ads

Etymology

Summarize

Perspective

Toten-Kopf translates literally to "Dead's Head", meaning exactly "dead person's head". Semantically, it refers to a skull, literally a Schädel. As a term, Totenkopf connotes the human skull as a symbol, typically one with crossed thigh bones as part of a grouping.

The common translation of "Totenkopf" as death's head is incorrect; it would be Todeskopf, but no such word is in use -- the English term death squad is called Todesschwadron,[30] not Totenschwadron. It would be a logical fallacy to conclude that usage varies only because of the German naming of the death's-head hawkmoth, which is called skull hawkmoth (Totenkopfschwärmer)[31] in German, in the same way that it would be a fallacy to conclude that the German word for night candle (i.e. Nachtkerze) would mean willowherb, just because the willowherb hawkmoth (Proserpinus proserpina) is called night candle hawkmoth (Nachtkerzenschwärmer, Proserpinus proserpina[32][33]) in German. Contemporary German language meaning of the word Totenkopf has not changed for at least two centuries. For example, the German poet Clemens Brentano (1778–1842) wrote in the story "Baron Hüpfenstich":

"Lauter Totenbeine und Totenköpfe, die standen oben herum ..."[34] (i.e. "A lot of bones and skulls, they were placed above ...").

Remove ads

See also

References

Bibliography

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads