Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising

Anti-Ottoman revolt in the Balkans (1903) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising, or simply the Ilinden Uprising, of August–October 1903 (Bulgarian: Илинденско-Преображенско въстание, romanized: Ilindensko-Preobrazhensko vastanie; Macedonian: Илинденско востание, romanized: Ilindensko vostanie; Greek: Εξέγερση του Ίλιντεν, romanized: Exégersi tou Ílinden), was an organized revolt against the Ottoman Empire, which was prepared and carried out by the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization,[4][5] with the support of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee, which included mostly Bulgarian military personnel.[6] The name of the uprising refers to Ilinden, a name for Elijah's day, and to Preobrazhenie which means Feast of the Transfiguration. Some historians describe the rebellion in the Serres revolutionary district as a separate uprising, calling it the Krastovden Uprising (Holy Cross Day Uprising), because on September 14 the revolutionaries there also rebelled.[7] The revolt lasted from the beginning of August to the end of October and covered a vast territory from the western Black Sea coast in the east to the shores of Lake Ohrid in the west.[note 1]

| Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Macedonian Struggle | |||||||

Map of the uprising in the regions of Macedonia and Thrace, with contemporary Ottoman frontiers and present-day borders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

IMRO Kruševo Republic Strandzha Commune | Ottoman Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 26,408 (IMARO figures)[3] | 350,931[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

IMARO figures:[3]

| 5,328 killed / wounded[3] | ||||||

The rebellion in the region of Macedonia affected most of the central and southwestern parts of the Monastir Vilayet, supported by Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionaries,[8][9][10][11][12] and to some extent of the Aromanian population of the region;[13] Provisional government was established in the town of Kruševo, where the insurgents proclaimed the Kruševo Republic, which was overrun after just ten days, on August 12.[14] On August 19, a closely related uprising organized by Thracian Bulgarian revolutionaries in the Adrianople Vilayet[15] led to the liberation of a large area in the Strandzha Mountains, and the creation of a provisional government in Vassiliko, the Strandzha Republic. This lasted about twenty days before being put down by the Turks.[14] The insurrection also affected the vilayets of Kosovo and Salonika.[16] In practice, this uprising was designed as a belated replica of the Bulgarian April Uprising of 1876, which finished disastrous, but which the national narrative had transformed into culmination of the anti-Ottoman struggle.[17]

By the time the rebellion had started, many of its most promising potential leaders, including Ivan Garvanov and Gotse Delchev, had already been arrested or killed by the Ottomans. The rebellion was supported by armed detachments which had infiltrated its area from the territory of the Principality of Bulgaria. Towards the end of the rising there was an attempt to force the Bulgarian government to send the army against the Ottomans, but the government was pressured by the Great Powers to refrain from military intervention.[18] The revolutionaries managed to maintain a guerrilla campaign against the Turks for almost three months, but the rising was crushed. This was followed by a mass wave of refugees from the areas of Macedonia and Southern Thrace, mostly to Bulgaria, but also to the US and Canada. Its greater effect was that it persuaded the European powers to attempt to convince the Ottoman sultan that he must take a more conciliatory attitude toward his Christian subjects in Europe.[19] Through bilateral agreement, signed in 1904, Bulgaria committed not to support the revolutionary movement, while the Ottomans undertook to implement the Mürzsteg Reforms, however neither happened.

The uprising is celebrated today in both Bulgaria and North Macedonia as the peak of their nations’ struggle against the Ottoman rule and thus it is still a divisive issue. While in Bulgaria it is considered as a general rebellion prepared by the joint revolutionary organization of the Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire, with a common goal autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople regions, in North Macedonia it is assumed that there were in fact two separate uprisings. Despite being organized by a single body, they were carried out by two different peoples with diverse goals, and practically the Macedonians were striving for their independence. Although the ideas of a separate Macedonian nation were supported then only by a handful of intellectuals abroad,[20] and to the eve of the 20th century the membership of the IMARO was allowed only for Bulgarians,[21][22] the post-WWII Macedonian rendition of history has reappraised the Ilinden uprising as an allegedly anti-Bulgarian revolt, led by ethnic Macedonians.[23][24] The leader of the IMARO and architect of the uprising Ivan Garvanov,[25] is regarded there a Greater Bulgarian agent who pushed the decision for a premature uprising.[26][27] Bulgarian Army officers' significant participation is represented there as an alien element,[28] while the fact the Uprising's leaders were Bulgarian schoolmasters,[29] is neglected. Recent calls for common celebrations, especially from the Bulgarian side, did little to change this state of affairs.[30]

Prelude

Summarize

Perspective

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

At the turn of the 20th century, the Ottoman Empire was crumbling, and the lands they had held in Eastern Europe for over 500 years were passing to new rulers. Macedonia and Thrace were regions of indefinite boundaries, adjacent to the recently independent Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian states, but themselves still under the control of the Ottoman Turks. Each of the neighbouring states based claims to Macedonia and Thrace on various historical and demographic grounds. The population, however, was highly mixed, and the competing historical claims were based on various empires in the distant past.[31][page needed] The competition for control took place largely via of propaganda campaigns, aimed at winning over the local population, and conducted largely through churches and schools. Various groups of mercenaries were also supported by the local population and the three competing governments.[31][page needed][32][page needed]

The most effective group was the Internal Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Organization (IMARO), founded in Thessaloniki in 1893. The group had a number of name changes prior to and subsequent to the uprising. It was predominantly Bulgarian and supported an idea for autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople regions within the Ottoman state with a motto of "Macedonia for the Macedonians".[32][page needed] IMARO's inspiration certainly belonged to the nineteenth-century Balkan practice whereby the powers maintained the fiction of Ottoman control over effectively independent states under the guise of autonomous status within the Ottoman state; (Serbia, 1829–1878; Romania, 1829–1878; Bulgaria, 1878–1908). Autonomy, in other words, was as good as independence. Moreover, from the Macedonian perspective, the goal of independence by autonomy had another advantage. More important, IMARO was aware that neither Serbia nor Greece could expect to obtain the whole of Macedonia and, unlike Bulgaria, they both looked forward to and urged partition. Autonomy, then, was the best prophylactic against partition, that would unite the multi-ethnic Macedonian population. However, the idea of Macedonian autonomy was strictly political and did not imply a secession from Bulgarian ethnicity.[33]

IMARO rapidly began to be infiltrated by members of Macedonian Supreme Committee, a group formed in 1895 in Sofia, Bulgaria, which enjoyed the covert but close cooperation with the Bulgarian government. This group was called the Supremists, and advocated annexation of the region by Bulgaria.[34][page needed] The two groups had different strategies. IMARO as originally conceived sought to prepare a carefully planned internal uprising in the future, but the Supremists preferred immediate raids and guerilla operations to foster disorder and a precipitate intervention from Bulgaria.[31][page needed][35][page needed][36][page needed] One of the founding leaders of IMARO, Gotse Delchev, was a strong advocate for proceeding slowly, because the result of a premature uprising would be tragic. The Supremists tried to impose their dominance over IMARO, they frequently urged a speedy uprising although they had little faith in the internal movement.[37] Their president Danail Nikolaev thought that IMARO's idea for a peasant uprising was unreal and because of that, Delchev was a brash youngster. Nikolaev sought that for the struggle to succeed, trained soldiers were needed and also clandestine aid and finance of the Bulgarian government.[26]

On the other hand, a smaller group of conservatives in Salonica organized a Bulgarian Secret Revolutionary Brotherhood (Balgarsko Tayno Revolyutsionno Bratstvo). The latter was incorporated in IMARO by 1900 and its members as Ivan Garvanov, were to exert a significant influence on the organization. They were to push for the Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising and later became the core of IMRO right-wing faction.[38][page needed] In 1899 Garvanov developed a friendship with Supremists' new leader Boris Sarafov, through which Garvanov managed to come to eminence in IMARO. Despite the mutual hostility, in this period IMARO and the Supremists collaborated and with Sarafov's help Garvanov and some of the Supremists became members of the IMARO regional committee in Salonica.

At the beginning of 1901, the arrested IMARO member Milan Mihaylov, who previously was a Supremists' member, revealed the names of other IMARO activists, as a result series of arrests were conducted, which would become known as the Salonica affair. Consequently many of the leaders of IMARO were arrested by the Ottomans, including the Central Committee members, others like Delchev took refuge in Bulgaria. In panic that IMARO will collapse, the Central Committee member Ivan Hadzhinikolov, before his arrest gave the archive and accounts to Garvanov. In this way Garvanov took control of the Central Committee and became its leader. Allegedly the imprisoned IMARO leaders were betrayed by Garvanov in order for him to seize control, thus in the following period the Central Committee was a tool of Garvanov and the Supremists and plans for the uprising began.[26]

In the beginning of January 1903, Garvanov summoned an IMARO congress in Salonica in order to push the idea for an uprising that spring. The representative of the Serres revolutionary district was firmly against, however in order for a positive answer, the participation at the congress was cautiously selected. After heated discussions, all the delegates present signed the protocol with an opinion on starting an uprising.[39] The decision to start an uprising was final, but Garvanov wanted to discuss it with the other top people of the organization, therefore, in mid-January, he arrived in Sofia. There, the decision on starting an uprising was discussed with Gotse Delchev, Gyorche Petrov, Pere Toshev, Hristo Matov, Hristo Tatarchev, Mihail Gerdzhikov, Kiril Parlichev, Dimitar Stefanov and others. It became clear that among the top people of the organization there was no unanimity on this issue, but eventually everyone accepted the idea.[40] However, Delchev remained strongly at the position that they are not ready, he went to the Serres region where he met with Yane Sandanski who shared his view. Later he went to Salonica for a meeting with Dame Gruev, who Delchev hoped that as a "heart of the organization" will argue for postponement of the uprising, but Gruev wanted it to proceed and defended the moral inspiration of the decision. Nevertheless, Delchev himself was killed by the Ottomans in May 1903.[26]

Meanwhile, in late April 1903, a group of young anarchists from the Gemidzhii Circle – graduates from the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki launched a campaign of terror bombing, the so-called Thessaloniki bombings of 1903. Their aim was to attract the attention of the Great Powers to Ottoman oppression in Macedonia and Eastern Thrace. As a response to the attacks, the Turkish Army and bashibozouks (irregulars) massacred many innocent Bulgarians in Thessaloniki, and later in Bitola.[citation needed]

By these circumstances the Supremists' plan went ahead. Under leadership from Garvanov, backed up by Gruev, the day chosen for the uprising was August 2 (July 20 in the old Julian calendar), the feast day of St. Elias (Elijah). This holy day was known as Ilinden. Garvanov, himself, did not participate in the uprising, because of his arrest and exile in Rhodes, so the leadership was left to Gruev and Sarafov. On 11 July, a congress at Petrova Niva near Malko Tarnovo set the date of 23 July for the uprising, then deferred it a bit more to 2 August. The Thrace region, around the Adrianople Vilayet was not ready, and negotiated for a later uprising in that region.[citation needed]

During this period, Racho Petrov's Bulgarian government supported IMARO's position that the rebellion was entirely internal. As well as Petrov's personal warning to Delchev in January 1903 to delay or even cancel the rebellion, the government sent out a circular note to its diplomatic representatives in Thessaloniki, Bitola and Edirne, advising the population not to succumb to pro-rebellion propaganda, as Bulgaria was not ready to support it.[41] Also, the IMARO was warned by the Minister of War Mihail Savov, that the uprising must be postponed until May 1904, by which time the Bulgarian Army would be ready for military intervention.[42]

Old Russian Berdan and Krnka rifles as well as Mannlichers were supplied from Bulgaria to Skopje following the demand for higher rates of fire by Bulgarian army officer Boris Sarafov.[43] In his memoir, Sarafov states that the main source of funds for the purchase of the weapons from the Bulgarian army came from the kidnapping of Miss Stone as well as from contacts in Europe.[44]

Ilinden Uprising

Summarize

Perspective

The General Staff of the Uprising was composed of Dame Gruev, Boris Sarafov and Anastas Lozanchev. On 28 July, the message was sent out to the revolutionary movements, though the secret was kept until the last moment. The uprising began on the night of August 2, and involved large regions in and around Bitola, around the south-west of Vardar Macedonia and the north-west of South Macedonia. That night and early the next morning, the town of Kruševo was attacked and captured by 800 rebels who were led by the locals Nikola Karev and Pitu Guli. On the day of the uprising the town of Smilevo was captured by the insurgents together with the General Staff and held off against the Ottoman siege for the next days. Other villages in the Bitola region were attacked as well, the local leader was Georgi Sugarev. The chetas of Luka Dzherov, Vancho Sarbakov and Arso Mitskov attempted to seize the town of Kičevo and engaged in several battles around it. In the Demir Hisar region, Yordan Piperkata with a group of 900 insurgents attacked the Ottoman garrison in the village of Pribilci, they further engaged in other battles in the region of Kičevo and Piperkata was eventually killed in one of them. Rebels led by Slaveyko Arsov attacked several villages in the region of Prespa, a fierce battle took place in Gorno Krušje, later the Ottoman bashi-bazouks in the village of Lefkonas were sieged for few days. The town of Kleisoura, near Kastoria, was taken by insurgents on August 5 under command of Vasil Chekalarov, after that the town of Nymfaio was captured for a short period as well. Later the chetas of Lazar Poptraykov and Chekalarov engaged in several battles in the region, of which the biggest was near the village of Dendrochori.

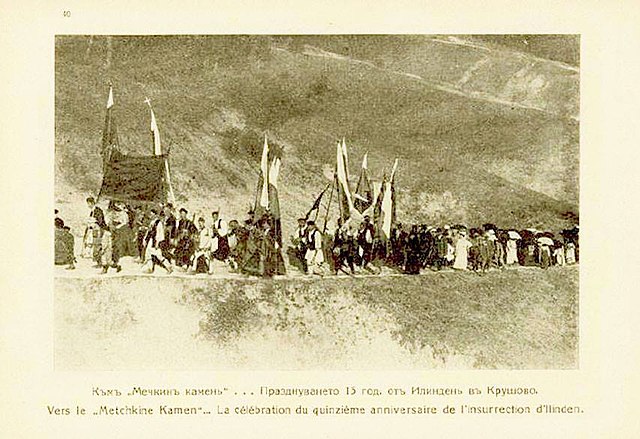

On August 4, under leadership of Nikola Karev, a local administration called Kruševo Republic had been set up. That same day and the next, Turkish troops made unsuccessful attempts to retake Kruševo.[14] On August 12, following the Battle of Sliva and the Battle of Mečkin Kamen, a force of 18,000 Ottoman soldiers recaptured and burned Kruševo.[26][45] It was held by the insurgents against the numerous Ottoman forces for ten days.

On August 14, rebels under the leadership of Nikola Pushkarov, attacked and derailed a military train near Skopje. Kleisoura was finally recaptured by the Ottomans on August 27.[14] Other regions involved in the uprising included Ohrid, Giannitsa, Gevgelija, Tikveš and Kratovo in this regions the operations were headed by Hristo Uzunov, Apostol Petkov, Sava Mihaylov, Argir Manasiev, Petar Yurukov and Atanas Babata. In the Thessaloniki region, operations were much more limited and without much local involvement, due in part to disagreements between the factions of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO). There was also no uprising in the Prilep area, immediately to the east of Bitola.[14]

The reason why the uprising was strategically chosen in the Bitola vilayet, and the broader southwestern region of Macedonia, was due to the fact that it was located the farthest from Bulgaria, attempting to showcase to the Great Powers that the uprising was purely of a Macedonian character and phenomenon.[48] Per one of the founders of IMARO – Petar Poparsov the idea to keep distance from Bulgaria, was because any suspicion of its interference could harm both sides: Bulgaria and the organisation.[49] In fact the uprising soon spread to the adjacent vilayets of Kosovo, Thessaloniki and Adrianople (in Thrace).[50]

Krastovden Uprising

Rebel chetas active in the regions of Pirin Macedonia and Serres, led by Yane Sandanski, and a chetas of the Supreme Committee led by Ivan Tsonchev and Anastas Yankov, engaged in battles with the large Turkish forces. The fighting began in the Melnik region even before the planned date on the Feast of the Cross (Krastovden in Bulgarian, September 27) day and lasted until October 21, the local population was not involved as much as in other regions. In the Razlog Valley the population joined in the uprising,[14] the rebels tried to seize the town of Razlog and several fierce battles took place in the area lasting until October 9.

In areas encompassing the uprising of 1903, Albanian villagers were in a situation of being either under threat from IMRO četas or recruited by Ottoman authorities to end the uprising.[51]

Preobrazhenie Uprising

According to Khadzhiev, the main goal of the uprising in Thrace was to give support to the uprisings further west, by engaging Turkish troops and preventing them from moving into Macedonia. Many of the operations were diversionary, though several villages were taken, and a region in Strandzha was held for around twenty days. This is sometimes called the Strandzha Republic or Strandzha Commune, but according to Khadzhiev "there was never a question of state power in the Thrace region."[14]

- On the morning of August 19, 1903, attacks were made on villages throughout the region, including Vasiliko (now Tsarevo), Stoilovo (near Malko Tarnovo), and villages near Edirne.

- On August 21, the harbor lighthouse at Igneada was blown up.

- Around September 3 a strong Ottoman force began reasserting their control.

- By September 8 the Turks had restored control and were mopping up.

Rhodope Mountains Uprising

In the Rhodope Mountains, Western Thrace, the uprising expressed only in some cheta's diversions in the regions of Smolyan and Dedeagach.[52]

Aftermath

Summarize

Perspective

The reaction of the Ottoman Turks to the uprisings was one of overwhelming force. The only hope for the insurgents was outside intervention, and that was never politically feasible. Indeed, although Bulgarian interests were favoured by the actions, the Bulgarian government itself had been required to outlaw the Macedonian rebel groups prior to the uprisings and sought the arrest of its leaders. This was a condition of diplomacy with Russia.[36][page needed] The waning Ottoman Empire dealt with the instability by taking vengeance on local populations that had supported the rebels. Casualties during the military campaigns themselves were comparatively small, but afterward, thousands were killed, executed or made homeless. Historian Barbara Jelavich estimates that about nine thousand homes were destroyed,[32][page needed] and thousands of refugees were produced. According to Georgi Khadzhiev, 201 villages and 12,400 houses were burned, 4,694 people killed, with some 30,000 refugees fleeing to Bulgaria.[14]

On September 29, the General staff of the Uprising sent the Letter N 534 to the Bulgarian government, appealing for immediate armed intervention:

"The General staff considers its duty to turn the attention of the respectable Bulgarian government to the disastrous consequences for the Bulgarian nation, if it does not carry out its duty towards its birth brothers here, in an impressive and active manner, as imposed by the power of the circumstances and the danger, which threatens the all-Bulgarian fatherland – through war."[53]

Still, Bulgaria was unable to send troops to the rescue of the rebelling fellow Bulgarians in Macedonia and Adrianople, Thrace. When IMARO representatives met the Bulgarian Prime-Minister Racho Petrov, he showed them the ultimatums by Serbia, Greece and Romania, which he had just received and which informed him of those countries' support for Turkey, in case Bulgaria intervened to support the rebels.[55] At a meeting in early October, the general staff of the rebel forces decided to cease all revolutionary activities, and declared the forces, excepting regular militias, to be disbanded.[14] The savagery of the insurrections and the reprisals did finally provoke a reaction from the outside world. In October, Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary and Nicholas II of Russia met at Mürzsteg and sponsored the Mürzsteg program of reforms, which provided for foreign policing of the Macedonia region, financial compensation for victims, and establishment of ethnic boundaries in the region.[34][page needed] The reforms achieved little practical result apart from giving more visibility to the crisis. The question of competing aspirations of Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, and local advocates for political autonomy were not addressed, and the notion of ethnic boundaries was impossible to implement effectively.

After the uprising, IMARO became more strongly associated with the Supremists, and with the goal of hegemony by Bulgaria.[36][page needed] In 1904, the Bulgarian government used its control over the Supremists to assume authority over IMARO. However, this resulted in IMARO splitting into a right-wing headed by Ivan Garvanov and Boris Sarafov, which favoured a pro-Bulgarian stance and a left-wing headed by Yane Sandanski.[56] The two wings engaged in outright conflict which meant mafia style killings on a larger scale. In this type of style, Garvanov and Sarafov were assassinated in 1907 by Todor Panitsa on the order of Sandanski.[26]

In any case, all of these concerns were soon overshadowed by the Young Turk revolution of 1908 and the subsequent dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.

Subsequent history

Summarize

Perspective

The Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913 subsequently split up Macedonia and Thrace. Serbia took a portion of Macedonia in the north, which roughly corresponds to North Macedonia. Greece took south Macedonia, and Bulgaria was only able to obtain a small region in the northeast, Pirin Macedonia.[34][page needed] The Ottomans managed to keep the Adrianople region, where the whole Thracian Bulgarian population was subjected to ethnic cleansing by the Ottoman Empire.[57][page needed] The rest of Thrace was divided between Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey following World War I and the Greco-Turkish War. Most of the local Bulgarian political and cultural figures were persecuted or expelled from Serbian and Greek parts of Macedonia and Thrace, where all structures of the Bulgarian Exarchate were abolished. Thousands of Macedonian Slavs left for Bulgaria. Some fled after the Greeks burned Kilkis, during the Second Balkan War, and the Treaty of Neuilly population exchange between Greece and Bulgaria saw 92,000 Bulgarians exchanged with 46,000 Greeks from Bulgaria.[58] Bulgarian (including the Macedonian dialects) was prohibited, and its surreptitious use, whenever detected, was ridiculed or punished.[59]

The Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization supported the Bulgarian Army during the Balkan Wars and World War I. After the Treaty of Neuilly, the combined Macedonian-Adrianopolitan revolutionary movement separated into two detached organizations: Internal Thracian Revolutionary Organisation and Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation and continued its struggle against Serbian and Greek authorities until 1934.[citation needed]

IMRO had de facto full control of Bulgarian Pirin Macedonia (the Petrich District of the time) and acted as a "state within a state", which it used as a base for hit and run attacks against Yugoslavia and Greece. IMRO began sending armed bands called cheti into Greek and Yugoslav Macedonia to assassinate officials and stir up the spirit of the oppressed population.[citation needed]

At the end of 1922, the Greek government started to expel large numbers of Bulgarians from Western Thrace into Bulgaria and the activity of the Internal Thracian Revolutionary Organization (ITRO) grew into an open rebellion. The organisation eventually gained full control of some districts along the Bulgarian border. In the summer of 1923, the majority of the Bulgarians had already been resettled to Bulgaria. Although detachments of the ITRO continued to infiltrate Western Thrace sporadically, the main focus of the activity of the organisation now shifted to the protection of the refugees into Bulgaria. IMRO's and ITRO's constant killings and assassinations abroad provoked some within Bulgarian military after the coup of 19 May 1934 to take control and break the power of the organizations.[citation needed]

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

Portrayals of the insurrections by later historians often reflect ongoing national aspirations. Historians from North Macedonia see them as a part of the move for an independent state as finally achieved by their own new nation. There is, in fact, very little historical continuity from the insurrections to the modern state, but Macedonian sources tend to emphasize the early goals of political autonomy when IMARO was established. The Supremacist faction pushed for the insurrections to take place in the summer of 1903, while the left wing argued for more time and more planning.[61] Historians from Bulgaria emphasize the undoubted Bulgarian character of the rebels, but tends to downplay the moves for political autonomy that were a part of the IMARO organization prior to the insurrections.[citation needed] Western historians generally refer simply to the Ilinden uprising, which marks the date on which uprising began. In Bulgaria it is more common to refer to the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie uprising, giving equal status to the activities commenced at Preobrazhenie near to the Bulgarian coast of the Black Sea and limiting an undue focus on the Macedonian region. Some sources recognize these as two related but distinct insurrections, and name them the Ilinden uprising and the Preobrazhenie uprising. Bulgarian sources tend to emphasize the moves within IMARO for hegemony with Bulgaria, as advocated by the Supremacist and the right wing factions.[citation needed]

The Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising was celebrated by the Macedonian and Thracian diaspora in Bulgaria and by all factions within the IMARO. It was commemorated officially in Macedonia under Bulgarian rule when it occupied then South Serbia during World War I[62] and World War II.[63] Celebrations occurred also in 1939 and 1940 in defiance of the ban by Serb authorities.[64] The leaders of the Ilinden uprising are today celebrated as heroes in modern-day North Macedonia. They are regarded as Macedonian patriots and as founders of the drive for Macedonian independence.[citation needed] The names of the IMARO revolutionaries like Gotse Delchev, Pitu Guli, Dame Gruev and Yane Sandanski were included into the lyrics of the anthem of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia Denes nad Makedonija ("Today over Macedonia"). There are towns named after the leaders in both Bulgaria and North Macedonia. Today, 2 August is the national holiday in North Macedonia, known as Day of the Republic,[65] which considers it the date of its first statehood in modern times. It is also the date on which, in 1944, a People's Republic of Macedonia was proclaimed at ASNOM as a constituent republic of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The ASNOM event is now referred as the 'Second Ilinden' in North Macedonia, though there is no direct link to the events of 1903. In Bulgaria Ilinden and Preobrazhenie days as anniversaries of the uprising are publicly celebrated on a local level, primarily in the Pirin Macedonia and Northern Thrace regions.[citation needed]

Controversy

Summarize

Perspective

There have been long-going disputes between parties in Bulgaria and North Macedonia about the ethnic affiliation of the insurgents. Macedonian historians consider that the qualification of the uprising as Bulgarian is biased, one of the asserts they use is that it was a uprising of the Macedonian people regardless in which church they prayed, school they learned and which national name they carried.[66] The opinion of most Macedonian historians and politicians is that Preobrazhenie uprising was a Bulgarian uprising, not related with the Ilinden one, which was organized by Macedonians.[67] Nevertheless, some of the Macedonian historical scholarship and political élite have reluctantly acknowledged the Bulgarian ethnic character of the insurgents.[68][69][70] Krste Misirkov, regarded nowadays in North Macedonia as one of the most prominent proponents of Macedonian nationalism of the early 20th century, states in his brochure On the Macedonian Matters (1903) that the uprising was supported and carried out primarily by that part of Macedonia's Slavic population which had Bulgarian national identity.[71]

The dominant view in Bulgaria is that at that time the Macedonian and Thracian Bulgarians predominated in all regions of the uprisings and that Macedonian ethnicity did still not exist.[72] More, the first name of the IMRO was "Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees". Initially its membership was restricted only for Bulgarians. It was active not only in Macedonia but also in Thrace. Since its early name emphasized the Bulgarian nature of the organization by linking the inhabitants of Thrace and Macedonia to Bulgaria, these facts are still difficult to be explained from the Macedonian historiography. They suggest that IMRO revolutionaries in the Ottoman period did not differentiate between 'Macedonians' and 'Bulgarians'. Moreover, as their own writings attest, they often saw themselves and their compatriots as 'Bulgarians' and wrote in Bulgarian standard language.[73] It has also to be noted that some attempts from Bulgarian officials for joint actions and celebration of the Ilinden uprising were rejected from Macedonian side as unacceptable.[74][75]

Nevertheless, on August 2, 2017, the Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borisov and his Macedonian colleague Zoran Zaev placed wreaths at the grave of Gotse Delchev on the occasion of the 114th anniversary of the Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising, after the previous day, both have signed a treaty for friendship and cooperation between the neighboring states.[76] The treaty also calls for a committee to "objectively re-examine the common history" of Bulgaria and Macedonia and envisages both countries will celebrate together events from their shared history.[77] According to Bulgarian officials, this commission has made little progress in its work for a period of two years.[78] Moreover in an interview on August 4, 2018 Zaev said that “the Ilinden uprising is Macedonian” and “if any citizen of Bulgaria wants to celebrate it, let them celebrate it.”[79] As result in 2020, Bulgaria blocked the candidature of North Macedonia to the European Union over an 'ongoing nation-building process' based on historical negationism of the Bulgarian legacy in the broader region of Macedonia.[80][81][82]

Honour

In Bulgaria

- Ilindentsi village in Strumyani Municipality, in Blagoevgrad Province is named after the uprising

- Preobrazhentsi village in Ruen Municipality, in Burgas Province is named after the uprising

- Ilinden village in Hadzhidimovo Municipality, in Blagoevgrad Province is named after the uprising

- Ilinden, Sofia is a district of Sofia, located in the western parts of the city, named after the uprising

- OMO Ilinden-Pirin, ethnic Macedonian organization in Bulgaria

- Ilinden (organization) was a veteran nonpolitical organization set up by Bulgarian refugees from Macedonia.

In North Macedonia

- Ilinden Municipality, in the Skopje region

- Ilinden, the seat of Ilinden Municipality

- Ilinden is a peak on Baba Mountain in Pelister National Park[83]

- FK Ilinden 1955 Bašino, football club near Veles

- FK Ilinden Skopje, football club in the village of Ilinden

Elsewhere

- Ilinden Peak on Greenwich Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica is named after the uprising

- Rockdale Ilinden FC football club in Sydney, Australia

Gallery

- L'Illustration magazine depicting Macedonian Bulgarian refugees crossing the Ottoman - Bulgaria border after the Ilinden Uprising.

- One of the Kruševo chetas during the uprising

- The events in the Ilinden Uprising as seen by the American New York Times; 14 August 1903.

- A convoy of captured Bulgarian IMRO activists

- L'Illustration magazine depicting a refugee demonstration in Sofia, Bulgaria after the crushing of the Uprising.

- A Puck Magazine satirical illustration showing the Russian puppets Bulgaria and Macedonia sword fighting, with the Bulgarian one about to decapitate the Macedonian, October 1903.[84]

- Museum in Smilevo dedicated to the Smilevo congress of May 1903, on which the decision for a uprising was confirmed and the date was chosen

See also

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising.

Footnotes

Notes

Sources

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.