David Dellinger

American pacifist and activist From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

David T. Dellinger (August 22, 1915 – May 25, 2004) was an American pacifist and an activist for nonviolent social change. Although active beginning in the early 1940s, Dellinger reached peak prominence as one of the Chicago Seven, who were put on trial in 1969.

David Dellinger | |

|---|---|

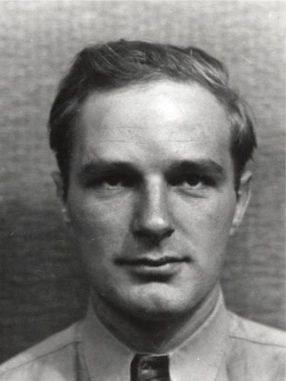

Dellinger's mug shot, 1943 | |

| Born | August 22, 1915 Wakefield, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | May 25, 2004 (aged 88) Montpelier, Vermont, U.S. |

| Education | Yale University (BA) New College, Oxford Union Theological Seminary |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for | Political activism, one of the Chicago Seven |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Peterson[1] |

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Dellinger was born in Wakefield, Massachusetts to a wealthy family. He was the son of Maria Fiske and Raymond Pennington Dellinger; his father was an alumnus of Yale University, a lawyer, and a prominent Republican and friend of Calvin Coolidge.[1] His maternal grandmother, Alice Bird Fiske, was active in the Daughters of the American Revolution.[1][2][3]

Dellinger graduated from Yale University with a Bachelor of Arts in economics, began a doctorate for a year at New College, Oxford, and studied theology at Union Theological Seminary of Columbia University with the intention of becoming a Congregationalist minister.[4][5] At Yale he had been a classmate and friend of the economist and political theorist Walt Rostow. Rejecting his comfortable background, he walked out of Yale one day to live with hobos during the Depression. While at Oxford University, he visited Nazi Germany and drove an ambulance during the Spanish Civil War. Dellinger, who opposed the war's victorious Nationalist faction, led by Francisco Franco, later recalled, "After Spain, World War II was simple. I wasn't even tempted to pick up a gun to fight for General Motors, U.S. Steel, or the Chase Manhattan Bank, even if Hitler was running the other side."[6]

Political career

Summarize

Perspective

During World War II, he was an imprisoned conscientious objector and anti-war agitator. In federal prison, he and fellow conscientious objectors, including Ralph DiGia and Bill Sutherland, protested racial segregation in the dining halls, which were ultimately integrated because of the protests.[7] He sat on the executive committee of the Socialist Party of America and the Young People's Socialist League, its youth section, until he left in 1943. In February 1946, Dellinger helped to found the radical pacifist Committee for Nonviolent Revolution.[2] In 1948, he co-founded the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors. He was also a long-time member of the War Resisters League, joining the staff in March 1955. In July–November 1951, Dellinger participated in the Paris-to-Moscow bicycle trip for disarmament with Ralph DiGia, Bill Sutherland, and Art Emery and sponsored by the Peacemakers; cyclists got as far as the headquarters of the Soviet Army in Vienna. “We were warned not to go to the Soviet zone. People who went to the army headquarters were sometimes never seen again. But we didn’t think that would happen to us. The worst that would happen was jail, and I already knew I could stand that. I was only worried about what I was putting my family through back in the States.”[8] The Paris-to-Moscow Bicycle Trip for Disarmament was a key inspiration for the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace in 1960–1961.[9]

In the 1950s and the 1960s, Dellinger joined freedom marches in the South and led many hunger strikes in jail. In 1956, he, Dorothy Day, and A. J. Muste founded the magazine Liberation as a forum for the pacifist, non-Marxist left.[10][11] Dellinger had contacts and friendships with such diverse individuals as Eleanor Roosevelt, Ho Chi Minh, Martin Luther King Jr., Abbie Hoffman, A.J. Muste, Greg Calvert, James Bevel, David McReynolds, and numerous Black Panthers such as Fred Hampton, whom he greatly admired. As chair of the Fifth Avenue Vietnam Peace Parade Committee, he worked with many antiwar organizations and helped bring King and Bevel into leadership positions in the 1960s antiwar movement. In 1966 Dellinger travelled to both North and South Vietnam to learn first-hand the impact of American bombing. He later recalled that critics ignored his trip to Saigon and focused solely on his visit to Hanoi.[12] In 1968, he signed the "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments to protest the Vietnam War,[13] and later became a sponsor of the War Tax Resistance project, which practiced and advocated tax resistance as a form of protest against the war.[14]

Chicago Seven trial

As US involvement in Vietnam grew, Dellinger applied Mahatma Gandhi's principles of nonviolence to his activism within the growing antiwar movement. One of the high points of this was the Chicago Seven trial over allegations that Dellinger and several others had conspired to cross state lines with the intention of inciting a riot, after antiwar protesters had interrupted the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The ensuing court case was turned by Dellinger and his co-defendants into a nationally publicized platform for putting the Vietnam War on trial. On February 18, 1970, they were acquitted of the conspiracy charge, but five defendants, including Dellinger, were convicted of crossing state lines to incite a riot. All of the defendants, along with their two lawyers, were given sentences for contempt of court; Dellinger was sentenced to 29 months and 16 days on 32 contempt counts.

Judge Julius Hoffman's handling of the trial, along with the FBI's bugging of the defense lawyers, resulted, with the help of the Center for Constitutional Rights, in the convictions being overturned by the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals two years later. The appeals court remanded the contempt citations for trial before a judge other than Julius Hoffman. Dellinger was eventually convicted on five contempt counts, but was sentenced to time already served.[15][16]

Subsequent activities

Dellinger spoke at the December 1971 John Sinclair Freedom Rally in Ann Arbor, Michigan.[17]

In the late 1970s, Dellinger spent two years teaching at Goddard College's Adult Degree Program and Vermont College.[18][19] In 2001, he was invited back to give the commencement address to the graduating class of Goddard's Residential Undergraduate Program.[20]

Dellinger also was a founder of Seven Days, an American alternative news magazine written from a leftist or anti-establishment perspective. Dellinger obtained the subscription list of Ramparts magazine, which ceased publication in October 1975.[21] Seven Days began preview editions in 1975, published regularly starting in 1977 but ceased publication in 1980.

In 1986, when his Yale class of 1936 held its 50th reunion, Dellinger wrote in the reunion book: "Lest my way of life sounds puritanical or austere, I always emphasize that in the long run one can't satisfactorily say no to war, violence, and injustice unless one is simultaneously saying yes to life, love, and laughter."[22]

For his lifelong commitment to pacifist values and for serving as a spokesperson for the peace movement, Dellinger was awarded the Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience award on September 26, 1992.

In 1996, during the first Democratic convention held in Chicago since 1968, Dellinger and his grandson were arrested along with nine others, including Civil Rights Movement historian Randy Kryn, Bradford Lyttle, and Abbie Hoffman's son Andrew, during a sit-in at Chicago's Federal Building.[23]

In 2001, Dellinger led a group of young activists from Montpelier, Vermont, to Quebec City to protest a conference that planned to create a free trade zone.[24]

Death

Dellinger died in Montpelier, Vermont, in 2004 after an extensive stay at Heaton Woods Nursing Home.[24] He suffered from Alzheimer's disease for years before his death.

Popular culture

- Peter Boyle played Dellinger in the 1987 film Conspiracy: The Trial of the Chicago 8.

- Dylan Baker voiced Dellinger in the 2007 animated documentary Chicago 10.

- In the 2010 film The Chicago 8 Dellinger was played by Peter Mackenzie.

- John Carroll Lynch portrayed Dellinger in the 2020 drama film The Trial of the Chicago 7.

Selected works

- Dellinger, David T., Revolutionary Nonviolence: Essays by Dave Dellinger, Indianapolis : Bobbs-Merrill, 1970

- Dellinger, David T., More Power Than We Know: The People’s Movement Toward Democracy, Garden City, N.Y. : Anchor Press, 1975. ISBN 0-385-00162-2

- Dellinger, David T., Vietnam Revisited: From Covert Action to Invasion to Reconstruction, Boston, MA : South End Press, 1986. ISBN 0-89608-320-9

- Dellinger, David T., From Yale to Jail: The Life Story of a Moral Dissenter, New York : Pantheon Books, 1993. ISBN 0-679-40591-7. (Dellinger's autobiography)

- Dellinger, David (1999). "Why I Refused to Register in the October 1940 Draft and a Little of What It Led To". In Gara, Larry; Gara, Lenna Mae (eds.). A Few Small Candles: War Resisters of World War II Tell Their Stories. Kent State University Press. pp. 20–37. ISBN 0-87338-621-3.

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.