Dasht-i-Leili massacre

Massacre in Afghanistan From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

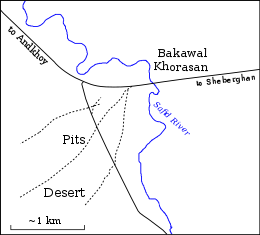

The Dasht-i-Leili massacre occurred in December 2001 during the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan when 250 to 2,000 Taliban prisoners were shot and/or suffocated to death in metal shipping containers while being transferred by Junbish-i Milli soldiers under the supervision of forces loyal to General Rashid Dostum[1][2][3] from Kunduz to Sheberghan prison in Afghanistan. The site of the graves is believed to be in the Dasht-e Leili desert just west of Sheberghan, in the Jowzjan Province.[4][5][6][7]

| Dasht-i-Leili massacre | |

|---|---|

A picture of a mass grave from the Dasht-i-Leili massacre published by the United Nations and Physicians for Human Rights. | |

| Location | West of Sheberghan, Jowzjan Province, Afghanistan |

| Coordinates | 36°39′24.17″N 65°42′20.71″E |

| Date | December 2001 |

| Target | Taliban prisoners of war |

Attack type | Massacre |

| Deaths | 250–2,000 |

| Perpetrators | Junbish-i Milli fighters |

| Assailants | Abdul Rashid Dostum (alleged, denied by Dostum) |

Some of the prisoners were survivors of the Battle of Qala-i-Jangi in Mazar-i-Sharif. In 2009, Dostum denied the accusations.[8][9][10] According to all sources, many of the prisoners died from suffocation inside the containers, and some witnesses claimed that those who survived were shot. The dead were buried in a mass grave under the authority of Commander Kamal.[citation needed]

The allegations have been investigated since 2002 by Physicians for Human Rights (PHR). PHR conducted two forensic missions to the site under the auspices of the United Nations in 2002.[11] In 2008, PHR reported that the grave had been tampered with.[12]

Controversy over responsibility and scale

Summarize

Perspective

In late 2001, around 8,000 Taliban fighters, including Chechens, Uzbeks and Arabs as well as suspected members of al-Qaeda, surrendered to the Junbish-i Milli faction of Northern Alliance General Abdul Rashid Dostum, a U.S. ally in the war in Afghanistan, after the siege of Kunduz. Several hundred of the prisoners, among them American John Walker Lindh, came to be held in Qala-i-Jangi, a fort near Mazar-i-Sharif, where they staged a bloody uprising which took several days to quell. The remaining 7,500 were loaded onto containers for transport to Sheberghan prison, a journey that in some cases took several days.[13] Human rights advocates say hundreds or thousands of them went missing.[citation needed]

In late 2001, Carlotta Gall, Jamie Doran and Newsweek began reporting rumors that Dostum's forces, who were fighting the Taliban alongside the US Special Forces, intentionally suffocated as many as 2,000 Taliban prisoners in container trucks in an incident that has become known as the Dasht-i-Leili massacre.[8][9][13][14][15][16][17]

The first allegations that dozens of prisoners had suffocated in the containers appeared in a December 2001 article in The New York Times.[18] A 2002 documentary named Afghan Massacre: The Convoy of Death by Jamie Doran produced testimony from eyewitnesses alleging hundreds or even thousands of prisoners had died, either during transport in the containers or being shot and dumped in the Dasht-i-Leili desert after arriving at the hopelessly overcrowded Sheberghan prison. Witnesses presented in the documentary also alleged that wounded and unconscious survivors of the container transports had been executed in the desert in the presence of U.S. soldiers. Doran's documentary, which was viewed by the European and German parliaments, caused widespread concern in Europe and among human rights advocates. It was not reported on in the United States mass media.[19]

We [the U.S. and Northern Alliance] could have wiped out every Talib on earth and no one would have cared ... There is no cover-up because nothing happened.... There are not that many bodies at Dasht-i-Leili

Allegations of American involvement were disputed by Robert Young Pelton, who had been in the area reporting for National Geographic and CNN. Pelton also said the number of prisoners who suffocated in the containers was roughly 250, a far smaller number than alleged in Doran's documentary. He claims he saw US medics treating some of the prisoners. He says some of the bodies may be victims of the Taliban or of Malik's executions in the 1990s.[20]

In 2016, Dostum spoke to Ronan Farrow, reluctantly admitting that local commanders had loaded prisoners from the uprising at Qala-i-Jangi into multiple containers and that American forces had been present. Dostum denied that either he or the Americans murdered the prisoners and would not directly say whether he had ordered the commanders to do this nor whether witnesses were later killed.[21]

Subsequent investigations

Summarize

Perspective

In 2002, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) led an investigation of alleged mass gravesites at Mazar.[22][23] A UN forensic team found fifteen recently deceased bodies in a six-yard trial trench dug at a 1-acre (4,000 m2) grave site and performed an autopsy on three of them, concluding that they had been the victims of homicide, the cause of death being consistent with suffocation, as described by the eyewitness reports featured in Doran's film.[24] A major Newsweek article on the massacre appeared in August 2002, raising questions about America's responsibility for the war crimes committed by its allies. It quoted Aziz ur Rahman Razekh, director of the Afghan Organization of Human Rights, asserting "with confidence" that "more than a thousand people died in the containers."[13]

The 2002 Newsweek article stated that "death by container" – locking prisoners in containers and leaving them to die in them – had been an established method of mass execution in Afghanistan for some years. As the containers were sealed, the prisoners began suffering from lack of air soon after being locked in them. According to witnesses in Doran's documentary, air holes were shot into the sides of some containers, killing several of those inside. Newsweek reported that drivers were punished for giving water to the prisoners, or punching holes into the containers. Survivors of the container transports, interviewed by Newsweek, recalled that after 24 hours the bound prisoners were so thirsty that they resorted to licking the sweat of each other's bodies. Some bit into the bodies of fellow prisoners. In the containers of these survivors, only 20 to 40 prisoners of an original 150 or more were still alive when the containers arrived at their destination.[13]

Further investigation of the mass grave sites were impeded by Rashid Dostum's continuing military control over the area and due to intimidation.[25] Physicians for Human Rights have claimed that the Bush administration consistently refused to respond to PHR's calls for investigation.[26] In 2008, the United States Defense Department and State Department released documentation per a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request by Raymond that indicated that 1,500 to 2,000 people were killed at Dasht-i-Leili.[1][27]

Ahmed Rashid wrote in 2008 that the prisoners were "stuffed in like sardines, 250 or more per container, so that the prisoners' knees were against their chests".[28] According to Rashid, only a handful survived in each of the thirty containers and UN officials reported that just six out of an original 220 survived in one of the containers.[28] The dead were buried by bulldozers in pits in the desert.[28] Rashid called the massacre "the most outrageous and brutal human rights violation of the entire war", which had occurred "despite the presence of US SOF in the region."[28]

American probe

Summarize

Perspective

On 10 July 2009, an article on the massacre by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist James Risen appeared in The New York Times.[1] Risen stated that human rights groups' estimates of the total number of victims "ranged from several hundred to several thousand" and that U.S. officials had "repeatedly discouraged efforts to investigate the episode".[1] Questioned about the article by Anderson Cooper of CNN during a trip to Africa, United States President Barack Obama was reported to have "ordered national security officials to look into allegations that the Bush administration resisted efforts to investigate a CIA-backed Afghan warlord over the killings of hundreds of Taliban prisoners in 2001."[29][30]

Excerpts from Doran's documentary Afghan Massacre: The Convoy of Death were broadcast on Democracy Now! on 13 July 2009, with images from the documentary shown on the programme's website.[24] The programme, which featured James Risen and Susannah Sirkin, deputy director of Physicians for Human Rights, claimed that "at least 2,000" prisoners of war had perished in the massacre.[24] Sirkin confirmed the claims made in Afghan Massacre: The Convoy of Death that eyewitnesses who had come forward with information on the incident had been tortured and killed, and stated that a FOIA document showed that the "U.S. government and, apparently, intelligence agency – it's a three-letter word that’s redacted of an intelligence branch of the U.S. government in the FOIA – they knew and reported that eyewitnesses to this massacre had been killed and tortured."[24]

Risen commented in the programme that in writing his article he "tried not to get caught up in something that I think in the past has slowed down some of the efforts by journalists to look into this. I think in the past one of the mistakes some journalists made was to try and prove a direct involvement by the U.S. personnel in the massacre itself. I frankly don't believe that any U.S. military personnel were involved in the massacre. And, you know, U.S. Special Forces troops who were traveling with Dostum have long maintained that they knew nothing about this. And, you know, so I tried not to go down that road." He added that "the investigation should focus rather on what happened afterwards in the Bush administration."[24]

A New York Times editorial on 14 July 2009 called the Bush administration's refusal to investigate a "sordid legacy".[31] Noting that Dostum was "on the C.I.A. payroll and his militia worked closely with United States Special Forces in the early days of the war", the editorial asked President Obama to "order a full investigation into the massacre. The site must be guarded and witnesses protected."[31] Edward S. Herman, writing in Z Magazine, commented that this renewed interest by The New York Times in the massacre, after a 7-year silence on the matter, was rather late in coming and coincided with Dostum's restoration to a position of power in Afghanistan prior to the August 2009 elections, in a move that the U.S. administration disapproved of.[19] Herman said that The New York Times had essentially looked whichever way the current U.S. administration had wanted it to look for the best part of a decade, and that this was also "part of the sordid legacy of the New York Times."[19]

On 17 July 2009, in an article published by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Dostum, recently reappointed to his government job by Afghan President Hamid Karzai, again described Doran's film as a "fake story", saying that the whole number of prisoners of war captured by his troops was less than the number Doran's film claimed had been killed, and denying there could have been any abuse of prisoners.[8] Dostum's column was sharply criticised by human rights groups.[9] In a rebuttal published by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in parallel to Dostum's piece, Sam Zarifi, the Asia-Pacific director for Amnesty International and a human rights investigator in Afghanistan in 2002, stated that "investigations carried out shortly after the alleged killings by highly experienced and respected forensic analysts from Physicians for Human Rights established the presence of recently deceased human remains at Dasht-e Leili and suggested that they were the victims of homicide."[9][10]

In December 2009 Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) renewed its call for the Obama administration's Department of Justice to investigate why the Bush administration impeded an FBI criminal probe in the wake of the 10 July 2009 front-page article in The New York Times. On 26 December 2009, the Asian Tribune published the full transcript of a video interview given by the officials of Physicians for Human Rights, detailing nearly eight years of advocacy and investigation.[32]

See also

Notes

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.