Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Curia

Assembly where issues are discussed and decided From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Curia (pl.: curiae) in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally probably had wider powers,[1] they came to meet for only a few purposes by the end of the Republic: to confirm the election of magistrates with imperium, to witness the installation of priests, the making of wills, and to carry out certain adoptions.

The term is more broadly used to designate an assembly, council, or court, in which public, official, or religious issues are discussed and decided. Lesser curiae existed for other purposes. The word curia also came to denote the places of assembly, especially of the senate. Similar institutions existed in other towns and cities of Italy.

In medieval times, a king's council was often referred to as a curia. Today, the most famous curia is the Curia of the Roman Catholic Church, which assists the Roman Pontiff in the hierarchical government of the Church.[2]

Remove ads

Origins

The word curia is thought to derive from Old Latin coviria, meaning 'a gathering of men' (co-, 'together' = vir, 'man').[3] In this sense, any assembly, public or private, could be called a curia. In addition to the Roman curiae, voting assemblies known as curiae existed in other towns of Latium, and similar institutions existed in other parts of Italy. During the republic, local curiae were established in Italian and provincial municipia and coloniae. In imperial times, local magistrates were often elected by municipal senates, which also came to be known as curiae. By extension, the word curia came to mean not just a gathering, but also the place where an assembly would gather, such as a meeting house.[4]

Remove ads

Roman curiae

Summarize

Perspective

In Roman times, curia had two principal meanings. Originally it applied to the wards of the comitia curiata. However, over time the name became applied to the senate house, which in its various incarnations housed meetings of the Roman senate from the time of the kings until the beginning of the seventh century AD.

Comitia curiata

The most important curiae at Rome were the 30 that together made up the comitia curiata. Traditionally ascribed to the kings, each of the three tribes established by Romulus, the Ramnes, Tities, and Luceres, was divided into ten curiae. In theory, each gens (family, clan) belonged to a particular curia, although whether this was strictly observed throughout Roman history is uncertain.[4][5]

Each curia had a distinct name, said to have been derived from the names of some of the Sabine women abducted by the Romans in the time of Romulus. However, some of the curiae evidently derived their names from particular districts or eponymous heroes.[5] The curiae were probably established geographically, representing specific neighborhoods in Rome, for which reason curia is sometimes translated as 'ward'.[4] Only a few of the names of the 30 curiae have been preserved, including Acculeia, Calabra, Faucia, Foriensis, Rapta, Veliensis, Tifata, and Titia.[6][5]

The assertion that the plebeians were not members of the curiae, or that only the dependents (clientes) of the patricians were admitted, and not entitled to vote, is expressly contradicted by Dionysius.[7] This argument is also refuted by Mommsen.[8]

Each curia had its own sacra, in which its members, known as curiales, worshipped the gods of the state and other deities specific to the curia, with their own rites and ceremonies.[9] Each curia had a meeting site and place of worship, named after the curia.[4] Originally, this may have been a simple altar, then a sacellum, and finally a meeting house.[5]

The curia was presided over by a curio (pl.: curiones), who was always at least 50 years old, and was elected for life.[4] The curio undertook the religious affairs of the curia. He was assisted by another priest, known as the flamen curialis.[5] When the 30 curiae gathered to make up the comitia curiata, they were presided over by a curio maximus, who until 209 BC was always a patrician.[4][5] Originally, the curio maximus was probably elected by the curiones, but in later times by the people themselves.[5] Each curia was attended by one lictor; an assembly of the comitia curiata was attended by thirty lictors.[5][10]

The comitia curiata voted to confirm the election of magistrates by passing a law called the lex curiata de imperio. It also witnessed the installation of priests, and adoptions, and the making of wills. The Pontifex Maximus may have presided over these ceremonies.[4] The assembly probably possessed much greater authority before the establishment of the comitia centuriata, which gradually assumed many of the curiate assembly's original functions.[4]

Meeting places

A curia could also be a building in which assemblies were held, such as for the senate. However, curiae for other municipal organisations also existed, such as the Curia Athletarum which was the headquarters of organised sport at Rome as well as some temples for worship.[11]

All places at which the senate met were templum (an inaugurated space).[12] Some of them where also called curiae,[13] as was the senate itself by metonymy.[14] The senate also met at various temples around Rome, such as the

Senate houses in the forum

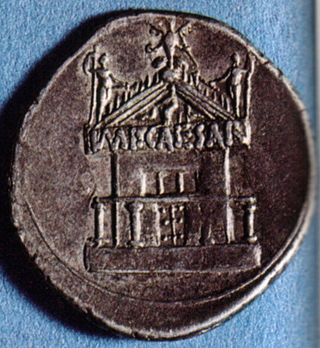

The most well known of the senate houses are those which were erected in the Roman Forum. The first known is the curia Hostilia which was the original senate house. According to Varro it was built by Tullus Hostilius, but it likely at various times had been rebuilt due to fire.[15] Aligned with the cardinal points and located north of the comitium, with that assembly place as essentially a forecourt, it was expanded by the dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 80 BC. However a few decades later, in 52 BC, it burned during the riotous funeral of Publius Clodius Pulcher. Rebuilt and again expanded by Faustus Sulla, the son of the dictator. The name curia Cornelia has been ascribed to both mens' curiae but that appellation is not attested in ancient sources.[16] It was decided to demolish Faustus Sulla's curia in 44 BC as part of Julius Caesar's forum renovations.[17] The reasons for its demolition are not entirely clear: Dio claims that the senate wished to erase the memory of Sulla; another claim, that the site was to be used for a temple to Felicitas, is not supported archaeologically.[18]

Caesar's renovation plans included the construction of a new curia Julia. However, Caesar was assassinated before it could be completed. It was eventually completed in 29 BC by Octavian, Caesar's heir, with a chalcidicum (a porch covered colonnade) before it. The emperor Domitian had it rebuilt as part of the construction of the Forum Transitorium, likely also moving to its current position at an angle from the rest of the Forum. The Domitianic curia Julia was destroyed in AD 283 by fire during the reign of Carinus.[19] The building, approximately 25.20 by 17.61 metres (82.7 ft × 57.8 ft), that still stands was built by the emperor Diocletian; it was converted into a church by Pope Honorius I (r. AD 625–638) but was deconsecrated and restored to its ancient form in 1935–38. The bronze doors of the Diocletianic structure, however, were removed to the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran in the 17th century.[20]

Other senate houses

Other curia for senatorial use also existed around Rome. The curia Pompeii (the Curia of Pompey) was constructed as part of Pompey's theatre and was the location where Julius Caesar was assassinated. The curia in Palatio, probably the Library of Palatine Apollo, was commonly used for senate meetings late in the reign of Augustus.[21] A curia Pompiliana is also discussed in the Historia Augusta, though this is usually identified with the curia Julia.[22]

Curiae Veteres

The Curiae Veteres was the earliest sanctuary of the thirty curiae. It is discussed by both Varro and by Tacitus, who mentions it as one point of the Palatine pomerium of Roma quadrata.[23] It is probable that this shrine was located at the northeast corner of the Palatine Hill. Its remains have likely been identified in excavations carried out by Clementina Panella.[24] As the Republic continued, the curiae grew too large to meet conveniently at the Curiae Veteres, and a new meeting place, the Curiae Novae, was constructed. A few of the curiae continued to meet at the Curiae Veteres due to specific religious obligations.[25][26]

Municipal curiae

In the Roman Empire a town council was known as a curia, or sometimes an ordo, or boule. The existence of such a governing body was the mark of an independent city. Municipal curiae were co-optive, and their members, the decurions, sat for life. Their numbers varied greatly according to the size of the city. In the Western Empire, one hundred seems to have been a common number, but in the East five hundred was customary, on the model of the Athenian Boule. However, by the fourth century, curial duties had become onerous, and it was difficult to fill all the posts; often candidates had to be nominated. The emperor Constantine exempted Christians from serving in the curiae, which led to many rich pagans claiming to be priests in order to escape these duties.[27]

Remove ads

Other curiae

Summarize

Perspective

The concept of the curia as a governing body, or the court where such a body met, carried on into medieval times, both as a secular institution, and in the church.

Medieval curiae

In medieval times, a king's court was frequently known as the curia regis, consisting of the king's chief magnates and councilors. In England, the curia regis gradually developed into Parliament. In France, the curia regis or Conseil du Roi developed in the twelfth century, with the term gradually becoming applied to a judicial body, and falling out of use by the fourteenth century.

Roman Catholic Church

In the Roman Catholic Church, the administrative body of the Holy See is known as the Roman Curia. It is through this Curia that the Roman Pontiff conducts the business of the Church as a whole.[2]

Among older religious orders, the governing council of the Superior General or Regional Superior and his or her assistants is referred to their Curia.

Modern usage

The Court of Justice of the European Union uses "CURIA" (in roman script) in its official emblem.

The term curia may refer to separate electoral colleges in a system of reserved political positions (reserved seats), e.g. during the British mandate of Palestine at the third election (1931) of the Asefat HaNivharim there were three curiae, for the Ashkenazi Jews, the Sephardi Jews and for the Yemeni Jews.[28][29][30][31]

In the United States Supreme Court an interested third party to a case may file a brief as an amicus curiae.[32]

Under the Fundamental Law adopted in 2011, Hungary's supreme court is called the Curia.

The Federal Palace of Switzerland, the seat of the Swiss Confederation, bears the inscription Curia Confœderationis Helveticæ.

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads