Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Cultural depictions of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V in popular culture From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558), the first ruler of an empire where the sun never set,[1] has traditionally attracted considerable scholarly attention and also raises controversies among historians regarding his character, his rule and achievements (or failures) in the countries in his personal empire, as well as various social movements and wider problems associated with his reign. Historically seen as a great ruler by some or a tragic failure of a politician by others, he is generally seen by modern historians as an overall capable politician, a brave and effective military leader, although his political vision and financial management tend to be questioned. Some criticize his inability to create or apply a consistent vision, while others defend him on the basis of the unprecedent nature of the task.[2][3][4][5]

Commenting on the events that commemorated the 500th anniversary (in 2000) of his birth, historian C. Scott Dixon writes that, "Born in Ghent on 24 February 1500, the first son of Philip of Habsburg and Juana of Castile, Charles would live to acquire the largest empire of the age. No other sovereign in Europe reigned over so many people or ruled over so many lands. By the year 1525, Charles V could lay claim to 72 separate titles, among them 27 kingdoms. 13 duchies, 22 counties and nine seigniories. He cast a shadow long enough to raise the concerns of the papal theologians, for here was a secular ruler who really could give living form to the medieval idea of a universal monarchy. It is no exaggeration to say that the political destiny of Europe in the sixteenth century was often in the hands of this Habsburg emperor, and it is thus little wonder that the anniversary of his birth has been commemorated in a series of public exhibitions, festivals, concerts, displays of art, learned conferences, and numerous publications."[6]

Remove ads

Historiography

Summarize

Perspective

Charles V's reputation among historians is controversial.

In his lifetime, the emperor had tried to influence his future image in several ways. His memoirs, dictated in 1550 on his way from Cologne to Speyer, is now considered unreliable. The emperor told his son Philip II about this book that any offence would be due to honest mistakes rather than intent.[7][8] He also had several publicists, chief among them was the Grand Chancellor himself, Mercurino di Gattinara.[9]

Christian R.Kemp notes that biographical materials between 1610 and 1800 tend to be political or religious propaganda, either "mythical hero worship or litanies of hatred".[7]

The current modern standard biography is the book Karl V. of Karl Brandi, translated in to English by C.V.Westwood (1939) as The Emperor Charles V.[10][3][11] It is centred on Germany and focuses on Charles V as the last German monarch to have attempted the establishment of a universal christian monarchy of medieval character. Álvarez's 1975 work Charles V: Elected Emperor and Hereditary Ruler, on the other hand, focuses on Spain at the expense of his other lands, but according to Maltby, is an effective supplement to Brandi's work in this way.[12] Peter Rassow's Karl V: der letzte Kaiser des Mittelalters (1957), (which is also German-centered[13]), continues with Brandi's view that Charles was a ruler with a medieval character (which is challenged by recent scholarship[14]).[15] Alfred Kohler praises Brandi's work as an extraordinary and valuable work even for modern readers, that clarifies the full severity of the conflict with France and the central importance of the European policy for the emperor, but thinks that he focuses too much on the dynastic side, the supposed peaceful intentions and the "Tu felix Austria nube" idea. Kohler remarks that Rassow makes a valuable contribution in exploring the idea of the emperor and Empire, and the question of harmonizing dynastic power and the unity of the Empire through the emperor.[16]

From a Belgian perspective, Charles de Terlinden's 1965 Charles Quint, empereur des deux mondes hails Charles V as "an illustrious pioneer of the idea of Europe [ ... ], a great European."[17] Peter Burke remarks that Charles's greatest posthumous successes are in the Low Countries, especially Belgium. Dixon does not disagree nor agree with him, but notes that the celebrations in Flanders in 2000 do strongly support Burke's point. Dixon points out some criticisms too and notes that political conditions of every era have produced some conflicting views. Dixon opines that there is not a structural difference between the Dutch and the Belgians, and Dutch historians have defended his importance in the unification process.[18]

From a global perspective, Brendan Simms summarises that Charles V focused the most on the Holy Roman Empire and the least on his possessions in the Americas:

The New World was an increasingly important part of the balance of power, but it was completely subordinate to European considerations. The Spanish colonial empire took up relatively little of Charles V's time. Its principal function was to provide resources to support his ambitions on the near side of the Atlantic: again and again, it was bullion from the Indies - a fifth of total revenue - which either funded campaigns against the French, Turks, and German princes directly, or provided the security against which the Emperor could borrow the great banking house of Fugger in Augsburg. For example, of nearly 2 million escudos' worth of treasury, the largest recipient was Germany, followed by the Low Countries. Charles's travels throughout his reign also show his priority quite clearly: he visited Italy on seven occasions, France on four, and England and Africa on two, and spent six long stays in Spain itself, but he travelled to Flanders and Germany on no fewer than nineteen occasions; he never visited the Americas. His imperial status stemmed from the Imperium Romanum, not the global sweep of his lands. In short, the Holy Roman Empire, not the emerging Spanish empire, provided the Imperial context in which the ambitions of Charles V played out.

— Europe, the Struggle for Supremacy, 1453 to the Present, p.87, Brendan Simms

Generally works by British and American historians have been noted as syntheses with little original interpretation, but Rebecca Ard Boone writes that some are good materials that introduce non-professionals to the matter.[19][3] A much praised work by an Anglo historian is Sir Geoffrey Elton's 1963 Reformation Europe 1517-1559, which describes Charles as having a deep sense of duty, loyal to his principles (unusual for a prince of his time), intelligent, capable in making viable a government that had to administer scattered lands and even wage wars by proxy and from a distance, but lacked "the depth of insight which might have made him a truly great king" – this problem showed itself the most in German matters.[20][21] Various modern historians attest to Charles's sense of honour and principles (although probably in a legal sense more than in a moral sense, and not in financial matters)[22][23] but points out his limited political vision.[24] James D. Tracy's Emperor Charles V, Impresario of War: Campaign Strategy, International Finance, and Domestic Politics examines the balance between military strategy, policy and financial matters in Charles's reign. Regarding the model of monarchia universalis, "Paradoxically, it may be the greatest significance of Charles's reign for European history lies not in what he did but in what he did not do: he either failed to achieve or did not even attempt the monarchia Gattinara had dreamed of".[25] Tracy notes though, that scholars have different views regarding the matter whether Charles ever embraced Gattinara's ideas or not. In his mature years, Charles refuted the idea that he had sought monarchia and emphasized that he was not an aggressors, but only his inherited lands and Christendom's defender against France, the Protestants and others. Tracy opines that his actions did not always reflected this though. For example, when he refused a joint command with Francis I of an expedition against the Turks, it was not clear he was acting as defender of Christendom or head of the house of Austria.[26] Tracy also notes that, " Charles not only left Europe's ingrained state pluralism essentially as he found it; he also helped make a broader basis of collaboration possible, if and when Christian states could overcome their habitual antagonisms."[27]

Kohler praises Tracy highly on the matter of campaigns and their financing.[5] Henry Kamen notes that Tracy "relates the emperor's military role in Spain to what he did in the rest of his dominions, and gives the best overall survey of imperial policy".[28]

Joachim Whaley notes that Charles did possess a political vision – a European one that focused on the West (unlike his grandfather Maximilian I who had a dual focus on both the East and the West, and unlike his brother Ferdinand I who was essentially a German emperor) and in the end more on Spain which provided more revenue while his absences (as well as his reluctance in allowing Ferdinand to share power according to Maximilian's desire) limited his authority in Germany and allowed the princes to assert their position more strongly.[29] Whaley remarks Charles's and Ferdinand's focus on non-German affairs during the crucial years of the mid-1250s, when Imperial Cities were forced to manage the rise of the common man in a way that estranged them from the crown, had important implications for the fact that a centralized, South German monarchy never arose from the alliance between crown and cities that Maximilian I had fostered.[30]

Some authors opine that the task was simply too much for one man to handle.[31] Geoffrey Parker writes that, "given the size and complexity of his transatlantic empire, the past provided no model".[32] Reviewing Parker's work, Francis P. Sempa notes that, "His [Charles V's] empire was the first modern European hegemon. Others—Louis XIV, Napoleon I, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Hitler's Germany, and the Soviet Union—would follow."[33]

Hajo Holborn opines that Charles's original plans were based on Burgundy, aiming to restore Charles the Bold's empire. Later he was guided by Gattinara towards medieval universalism and a focus on Italian matters.[34] Jean-Marie Cauchies also opines that for a long time he remained a Burgundian not only in person but also geographically. When he abdicated, in 1555, Charles remarked that when he aspired for the crown of Otto, he though about protecting his estates, but especially the Low Countries.[35]

Boone comments on the historiography of Charles V as the following:[3]

The figure of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (b. 1500–d. 1558), looms large over a wide swath of human experience in the 16th century. His empire impacted the direction of history in the Americas, Europe, and the Middle East. The military, diplomatic, and dynastic force of his empire weighed on cultural movements that included the Reformation, Renaissance, print revolution, witch trials, global trade, and colonization. The interplay of his narrow and shortsighted vision on one side and his military courage, administrative acumen, and devotion to duty as he understood it on the other has intrigued historians for nearly five hundred years. Every generation has found him relevant, but for different reasons. By all accounts he was talented in language acquisition. He also had the energy, intellect, and desire to understand the minutia of administrative and diplomatic business. His presence on the battlefield and documented courage helped him maintain the loyalty of his subjects. In short, he seems to have been a “good enough” emperor. Although he did not maintain political or religious unity in his empire, he defended the lands he inherited and maintained them under his family's rule. His publicists devised an imperial program focused on his personal power as a ruler chosen by God to defend Christianity from internal and external forces of evil. The contemporary shift toward authoritarian rule in many countries today has given this program new relevance.

- Álvarez, Manuel Fernández; Lalaguna, Juan (1975). Charles V: Elected Emperor and Hereditary Ruler. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-87001-3. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- Blockmans, Wim (2008). Karel V : keizer van een wereldrijk, 1500-1558. Kampen: Omniboek. ISBN 9789059774070.

- Boone, Rebecca Ard (2021). "Charles V, Emperor". Oxford Bibliographies Online (obo). Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- Brandi, Karl (1960). The Emperor Charles V: The Growth and Destiny of a Man and of a World-empire. J. Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-60916-6. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Elton, Sir G. R. (9 August 2016). Reformation Europe, 1517-1559. Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78720-055-5.

- Ferdinandy, Michael de (2021). Charles V Accomplishments, Reign, Abdication, & Facts Britannica. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- Kemp, Christian Raul (2011). The Hapsburg and the Heretics: An Examination of Charles V's Failure to Act Militarily Against the Protestant Threat (1519-1556) (Thesis). Brigham Young University - Provo. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- Kleinschmidt, Harald (24 October 2011). Charles V: The World Emperor. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7440-3.

- Kohler, Alfred (2005). Karl V.: 1500 - 1558; eine Biographie (in German). C.H.Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-52823-1. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- Maddens, Klaas (1975). De beden in het graafschap Vlaanderen tijdens de regering van Keizer Karel V (1515-1550) (Thesis). KU Leuven.

- Maltby, William S. (25 March 2002). The Reign of Charles V. Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-137-15954-0. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- Morren, Paul (2004). Van Karel de Stoute tot Karel V (1477-1519) (in Dutch). Garant. ISBN 978-90-441-1545-1.

- Parker, Geoffrey (25 June 2019). Emperor: A New Life of Charles V. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-24102-0. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- Rassow, Peter; Schalk, Fritz (1960). Karl v., der Kaiser und seine Zeit; hrsg. von Peter Rassow und Fritz Schalk. Böhlau. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- Soly, Hugo; Blockmans, Wim, eds. (1999). Karel V, 1500-1558 : de keizer en zijn tijd. Antwerpen: Mercatorfonds. ISBN 9789061534334.

- Tracy, James D. (14 November 2002). Emperor Charles V, Impresario of War: Campaign Strategy, International Finance, and Domestic Politics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81431-7. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

Remove ads

Depictions in legends and arts

Summarize

Perspective

References to Charles in popular culture include a large number of legends and folk tales; literary renderings of historical events connected to his life and romantic adventures, his relationship to Flanders, and his abdication; and products marketed in his name.[36]

The impact of Charles's patronage and personality on European arts has been notable. While reviewing his impact on Italian arts, William Eisler notes that there is no serious scholarly work that investigates his patronage yet.[37] Having been the arch-opponent of the French king Francis I in his lifetime, French traditional historical writings have tended to possess a degree of hostility towards the emperor, although in various works (both scholarly and artistic) he appears sympathetic. Today, he is not seen as an enemy anymore.[38]

Legends and anecdotes

- According to Vasari, when being painted by Titian, Charles V noticed that the painter dropped his brush. Charles picked it up for him and told him, while Titian demurred, that "Titian is worthy to be served by Caesar."[39][40]

This anecdote has inspired works such as paintings by Pietro Antonio Novelli (1729-1804) and Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleury (1797–1890).[41][42]

- A legend originating from the peasantry in Hesse tells that after a victorious battle, a rock opens and swallows Charles V and his army. The emperor sleeps inside the mountain. Every seven years, the emperor and his army issue forth in a Wild Chase which causes a storm and the neighing of horses will be heard. The spirit procession then returns to the mountain. The legend is connected to the "Barbarossa sleeping in the mountain" and other similar legends.[43]

- The Faust legend: The image of Charles V plays a role in the development of this legend. The early versions of the legend usually involve Maximilian (Charles's paternal grandfather), Mary of Burgundy (Charles's paternal grandmother) and the humanist Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516). Trithemius supposedly conjured the spirit of the deceased Mary (in certain versions also with ancient heroes) for Maximilian. In the versions (beginning with a 1587 anonymous account) that involve Charles, the emperor wanted to see Alexander, ancient heroes and Alexander's wife (or concubine) who had a birthmark that Charles had heard about. While the early versions highlight the love and human weakness that are exploited, the latter is propaganda that portrays the emperor as ambitious and glory-hungry instead.[44][45] The Charles versions influence Marlower's Doctor Faustus, mentioned below.

Tapestries

Larry Silver notes that while Maximilian, Charles's grandfather, preferred woodcuts (as this medium was cheap) for "portable political claims", Charles V combined luxury and mobility in the form of tapestries, which were often commissioned by relatives and prominent subjects rather than the emperor himself.[46]

- Arrival of the statue of Notre-Dame to Brussels, from the tenture of Notre-Dame du Sablon, design attributed to Bernaert van Orley, 1518, wool and silk (Cinquantenaire Museum - Brussels, Belgium) features Charles and his brother Ferdinand as litter carriers. The kneeling figure wearing a crown on the left is Philip the Fair.[47][48] Silver remarks that, "Compared with earlier Flemish tapestries, his weavings provided heightened suggestions of depth and also inserted Italianate motifs within the border and frame decorations."[49]

- The Nassau Genealogy (ca. 1529–31, now destroyed but designs survive), commissioned by the Nassau family "pairs male and female equestrian figures as in the Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen woodcut cavalcade of the counts of Holland, a recent suite (1518) that culminated with Maximilian, Mary of Burgundy, Philip the Fair, and Charles V".[49]

- The Battle of Pavia, woven in seven pieces, in the Netherlands, from designs by Bernaert van Orley, and presented to Charles V in 1531, commemorate the 1527 Battle of Pavia.[50]

- The Conquest of Tunis, twelve-parted. circa 1550–54, was designed by Jan Vermeyen, with the help of Pieter Coecke van Aelst and woven in the workshop of Willem de Pannemaker in Brussels.[51] According to Silver, this is "the most encompassing of all tapestry cycles for Charles V" and "his vast commemoration of his updated version of the crusade against Islam, specifically against its naval forces". He also remarks, "The Conquest of Tunis surpasses even The Battle of Pavia in its maplike specificity and full documentation of the emperor's crusading Mediterranean campaign."[52]

Music

- The papal composer Constanzo Festa composed Te Deum laudanus which was sung when Charles entered the Church of San Antonio during his 1530 coronation.[53]

- Jacquet of Mantua composed Repleatur os meum for Charles's coronation in 1530.[54]

Charles's motto "Plus ultra" appeared as a textual motto in several musical works produced during Charles's reign. Ferer lists these works as the following: "They include two anonymous chansons, a mass entitled Missa Plus oultre by Johannes Lupi, a chanson and intabulation for two lutes by Nicolas Gombert, and a lost chanson by Costanzo Festa.[55] An anonymous setting of the motto, Plus oultre pretens parvenir, was most likely composed near the beginning of Charles's reign. Its text affirms his vision of expanding his realm and advancing the faith, as well as his resolve to establish a universal empire.[...] Plus oultre prefens parvenir is extant in VienNB 9814, a manuscript probably copied between 1519 and 1525 and part of the Alamire Netherlands court complex."

- Cristóbal de Morales's five part mass "Missa super l'homme armé" was likely composed for the marriage between Charles and Isabella, "reflects in the original motet text the kind of strength with which Catholic Charles was arming himself against Protestants".[56]

- The monumental motet Virgo Prudentissima, originally composed for Maximilian I and dedicated to the Virgin Mary, was rewritten by Hans Ott to be rededicated to Christ as Christus filius Dei (all Marian references were replaced) and Maximilian was replaced with his grandson, around 1537–1538.[57]

- Carl Loewe (1796–1869) wrote four historical ballads about Charles V.[58]

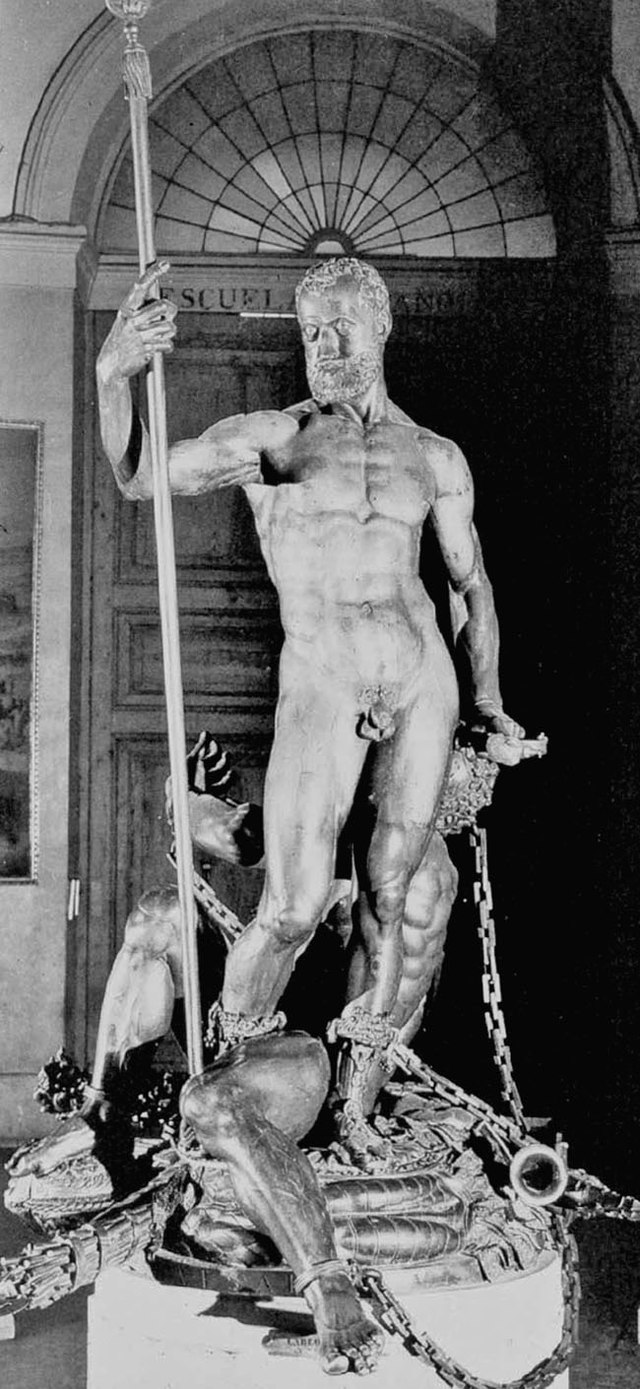

Public monuments

In his lifetime, artists usually accompany him in his expeditions. These artists tended to depict him as a Roman emperor (a "calculated feat", according to Sacheverell Sitwell) and this continued after his death. The monument in Palermo is a notable example.[60]

- The Charles V Monument in Palermo was erected in 1631 and depicts him triumphant following the Conquest of Tunis.

- Among other posthumous depictions, there are statues of Charles on the facade of the City Hall in Ghent and the Royal Palace of Caserta. The monument to Charles in Vrijdagmarkt was dedicated by Albert and Isabella in 1600.[61]

In the nineteenth century, as governments erected statues of famous rulers and heroes to bolster patriotic feelings, there was renewed interest in Charles V. As his physical attributes were not suitable to depict embodiment of kingship, textbooks tended to present him as embodiment of devotion to duty, despite his physical frailty and suffering. Maria Theresa selected Charles V, Charlemagne together with other Habsburg patrons of the arts like Charles VI, Rudolf I to be included in a group of monument in Vienna to glorify her reign and solidify Austria's status as the inheritor of Carolingian dynasty.[62]

- A statue of Charles, donated by the city of Toledo, was erected in 1966 in the Prinsenhof in Ghent where he was born.[63]

- An imperial resolution of Franz Joseph I of Austria, dated February 28, 1863, included Charles V in the list of the "most famous Austrian rulers and generals worthy of everlasting emulation" and honored him with a life-size statue, made by the Bohemian sculptor Emanuel Max Ritter von Wachstein, located at the Museum of Military History, Vienna.[64]

Paintings and engravings

Other than Titian, whom he compared to Apelles, other notable court painters of Charles V included Bernaert van Orley and Pieter Coecke.[65][66]

- Titian created several paintings of the emperor. The famous Equestrian Portrait of Charles V (1548) has inspired later royal painters, such as Anthony van Dyck's Equestrian Portrait of Charles I.[68] This portrait is considered the "first painted or sculpted equestrian monument sin antiquity dedicated to a living individual." The painting implied the image of a statue of Marcus Aurelius, who Charles often incorporated into his iconography (the royal historiographer Guevara wrote Relox de principes in imitation of Marcus's Meditations - an effort considered by Springer as central to this association).[69]

- In 1530, following Charles's coronation in Bologna, Parmigianino painted Carlo V come dominatore del mondo (Charles V as ruler of the world). The painting reflects Charles's self-identification as Hercules. Later, Rubens produced a painting based on this with the same name. The imperial pose would later be used by Rubens for Marie de' Medici (in the guise of Justitia) in his Marie de' Medici cycle.[70][71]

- Around 1816, Goya created the etching Carlos V. lanceando un toro en la plaza de Valladolid (Charles V Spearing a Bull in the Ring at Valladolid) as part of his famous series La Tauromaquia. Charles V's association with the art of bullfighting is a point of pride for many Spaniards. The mystical atmosphere is added by "the rainbowlike shaft of light that appears at the upper right-hand side of the image".[72][73]

- In 1878, Hans Makart painted The Entrance of Emperor Charles V into Antwerp in 1520. The scantily dressed women surrounding the emperor were lent the features of famous Viennese salon beauties.[74]

- In 1880, on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of Belgian independence, Albrecht de Vriendt painted the work Philip I, the Handsome, Conferring the Order of the Golden Fleece on his Son Charles of Luxembourg (Philippe Ier le Beau, conférant à son fils Charles de Luxembourg le titre de Chevalier de l'Ordre de la Toison d'Or). "Vriendt evokes the splendor of chivalric rites, setting a precedent of protocol for the new monarchy. Amid the lavish trappings of the princely household, Philip the Handsome (1478–1506) theatrically bestows the Order of the Golden Fleece on his one-year-old son, Charles (1500–1558), who later became Europe's most powerful ruler as the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V".[75]

- Willem Geets (1838–1919) was the author of several famous paintings that depict Charles V. In 1984, a piece (that depicts Princess Isabella) of the painting Puppet show at the court of Margaret of Austria (1893) was stolen. The reason and the perpetrator are still unknown. The painting Emperor Charles V and Barbara Blomberg is the basis of the 1894 woodcut in Museen der Stadt Regensburg.[76][77]

Literature

- Sempere's La Carolea (1560) and Luis Zapata's Carlos Famoso (1566) are epics about Charles V. These works belong to the group of heroic poems about Charles, that are called the Caroliads.[78][79]

- Cervantes's Don Quixote mentions Charles V in many places. José Antonio Maravall even sees the work as a nostalgic tribute to the emperor.[80]

- In De heerelycke ende vrolycke daeden van Keyser Carel den V, published by Joan de Grieck in 1674, the short stories, anecdotes, citations attributed to the emperor, and legends about his encounters with famous and ordinary people, depict a noble Christian monarch with a perfect cosmopolitan personality and a strong sense of humour. Conversely, in Charles De Coster's masterpiece Thyl Ulenspiegel (1867), after his death Charles V is consigned to Hell as punishment for the acts of the Inquisition under his rule, his punishment being that he would feel the pain of anyone tortured by the Inquisition.[81] De Coster's book also mentions the story on the spectacles in the coat of arms of Oudenaarde, the one about a paysant of Berchem in Het geuzenboek (1979) by Louis Paul Boon, while Abraham Hans (1882–1939) included both tales in De liefdesavonturen van keizer Karel in Vlaanderen.

- Achim von Arnim's Isabella von Ägypten. Kaiser Karl des Fünften erste Jugendliebe (novella, 1812) is a story about love between Charles and the Gypsy princess Isabella, whose mission is to free her "coarse people" and lead them back to Egypt, their legendary homeland.[82] Arnim's story is connected to the imperial idea of universal rulership (of which the incarnation in Arnim's time was Napoleon) and the Virgin Astraea, associated with the Holy Roman Empire and here represented by the Gypsy princess.[83]

- Alexander Dumas's novel El Salteador (1854), published in English under the name The brigand : a story of the time of Charles the Fifth; and, The horoscope, a romance of the reign of Francis Second. is about Charles V (here Carlos I and events in Spain in 1519).[84][85]

- Lord Byron's Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte refers to Charles as "The Spaniard".[86]

- Charles V is a notable character in Simone de Beauvoir's All Men Are Mortal.[87]

- In The Maltese Falcon, the title object is said to have been an intended gift to Charles V.[88]

- Las Casas vor Karl V. Szenen aus der Konquistadorenzeit (Las Casas before Charles V. Scenes from the Conquistador Period is a work by Reinhold Schneider, published in 1938 in Leipzig. The story is about the argument between Bartolomé de las Casas and Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda regarding treatment of the natives in front of Charles V.[89]

- Charles Quint: Against this rock is a 1943 novel about Charles V by Louis Zara.[90]

- He is a character in Günter Krieger's Der Aachener Hund: Als Albrecht Dürer zur Krönung Karls V. kam.[91]

- A Matter of Pride (Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor): King, Soldier, Love is a 2008 novel by Linda Carlino.*[92]

- El Secreto del Emperador by Amelie de Bourbon is a 2017 novel about his retirement in Yuste.[93]

Plays

- Charles V appears as a character in the play Doctor Faustus by the Elizabethan playwright Christopher Marlowe. In Act 4 Scene 1 of the A Text, Faustus attends Court by the Emperor's request and with the assistance of Mephistopheles conjures up spirits representing Alexander the Great and his paramour as a demonstration of his magical powers.[94]

- Kaiser Karl V is a 1918 drama by Otto Zarek.[95]

Opera

Charles-Quint au monastère de Yuste by Eugène Delacroix

Carlos V recibe en Yuste la visita de San Francisco de Borja (Museo del Prado by Joaquín María Herrer y Rodríguez

Charles V's retirement at the Monastery of Yuste is a popular topic for artists.

- Fierrabras (opera) (1823) is an opera by Franz Schubert with the setting being Charles V's war against the Moors. Charles's daughter Emma is loved by Fierrabras, son of the leader of the Moors and Eginhard, a Spanish knight.[96]

- In the third act of Giuseppe Verdi's opera Ernani (1830), the election of Charles as Holy Roman Emperor is presented. Charles (Don Carlo in the opera) prays before the tomb of Charlemagne. With the announcement that he is elected as Carlo Quinto he declares an amnesty including the eponymous bandit Ernani who had followed him there to murder him as a rival for the love of Elvira. The opera, based on the Victor Hugo play Hernani, portrays Charles as a callous and cynical adventurer whose character is transformed by the election into a responsible and clement ruler.[97]

- In another Verdi opera, Don Carlo, the final scene implies that it is Charles V, now living the last years of his life as a hermit, who rescues his grandson, Don Carlo, from his father Philip II and the Inquisition, by taking Carlo with him to his hermitage at the monastery in Yuste.[98]

- Ernst Krenek's opera Karl V (opus 73, 1930) examines the title character's career via flashbacks.[99]

Architecture

- The Palace of Charles V in Granada was commissioned by Charles V. Construction bagan in 1527 but only finished in 1637. The construction of a monumental Italian or Roman-influenced palace in the heart of the Nasrid-built Alhambra symbolized Charles V's imperial status and the triumph of Christianity over Islam achieved by his grandparents (the Catholic Monarchs).[100]

- The Plaza del Emperador Carlos V is a square in the city of Madrid that is named after Charles V.

Armour

Among the notable armourers who worked for Charles were the brothers Filippo and Francesco Negroli, Desiderius Helmschmid (1513–1579). Filippo was perhaps the first Italian armorer who constructed pseudo-antique helmets from single plates rather than combining multiple pieces as was the common practice of the time.[104]

- A round shield carries the image of Medusa (called the Medusa shield) and a burgonet were crafted by the Negroli and presented to Charles by his brother Ferdinand after in his 1535 entry to Naples, to celebrate his Tunis victory. The burgonet opens like a Roman helmet, with its idiosyncratic form assuming the figure of the hero Hercules. Tritons and Nereids appear on the shield alluding to naval expeditions to Africa. Figures of four great Africa heroes of ancient Rome appear on the shield, as medallions: Scipio, Caesar, Augustus and Claudius. These symbols identifying Charles with ancient African victors.[105]

- Desiderius Helmschmid made for Charles a breastplate that portrays him as Santiago Matamoros. This also seems to be an allegorical depiction of Charles' s triumph over Barbarossa in 1535.[106]

Food

- A Flemish legend about Charles being served a beer at the village of Olen, as well as the emperor's lifelong preference of beer above wine, led to the naming of several beer varieties in his honor. The Haacht Brewery of Boortmeerbeek produces Charles Quint, while Het Anker Brewery in Mechelen produces Gouden Carolus, including a Grand Cru of the Emperor, brewed once a year on Charles V's birthday.[107][108][109][110] Grupo Cruzcampo's Legado De Yuste is connected to Charles, his Flemish origin and his last days at the monastery of Yuste.[111]

- Carlos V is the name of a popular chocolate bar in Mexico. Its tagline is "El Rey de los Chocolates" or "The King of Chocolates" and "Carlos V, El Emperador del Chocolate" or "Charles V, the Emperor of Chocolates."[112]

Television and film

- He is portrayed by Conrad Veidt in the 1924 silent film Carlos and Elisabeth.[113]

- Charles V is portrayed by Hans Lefebre and is figured prominently in the 1953 film Martin Luther, covering Luther's years from 1505 to 1530.[114]

- He is portrayed by James Kirby in the 1983 Martin Luther, Heretic.[115]

- Charles V is portrayed by Torben Liebrecht and is figured prominently in the 2003 film Luther covering the life of Martin Luther up until the Diet of Augsburg.[116]

- Charles V is portrayed by Sebastian Armesto in one episode of the Showtime series The Tudors.[117]

- Charles V is the main subject of the TVE series Carlos, Rey Emperador and is portrayed by Álvaro Cervantes.

- Kaiser Karl V. - Wunsch und Wirklichkeit (2020, directed by Wilfried Hauke) is an Arte documentary about the emperor.[118]

- Das Luther-Tribunal. Zehn Tage im April is a ZDF docudrama about Martin Luther, focusing on the ten days in April of the 1521 Diet of Worms. Mateusz Dopieralski plays Charles (Karl V.).[119]

- Charles V is played by Adrien Brody in the upcoming 2022 movie Emperor.[120]

Remove ads

Commemoration

The Ommegang of Brussels, organized annually in Belgium (now twice a year), celebrates the 1549 entry of Charles and his son Philip.[121]

Charles V has been commemorated over time throughout Europe. Austrian rulers such as Maria Theresa and Franz Joseph viewed him as of their great predecessors and honored his figure.[122] The 400th anniversary of his death, celebrated in 1958 in Francoist Spain, brought together the local national catholic intelligentsia and a number of European (Catholic) conservative figures, underpinning an imperial nostalgia for Charles V's Europe and the Universitas Christiana, also propelling a peculiar brand of europeanism.[123] In 2000, celebrations for the 500th anniversary of Charles's birthday took place in Belgium.[124]

See also

- Cultural depictions of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

- Mary of Burgundy in arts and popular culture

- Cultural depictions of Philip II of Spain

- Cultural depictions of Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Otto III, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Conrad II, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor

- Titian

Remove ads

External links

Bibliography and further reading

Charles V and music

- Ferer, Mary Tiffany (2012). Music and Ceremony at the Court of Charles V: The Capilla Flamenca and the Art of Political Promotion. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-699-5. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- Froidebise, Pierre (1965). Music from the Chapel of Charles V. Nonesuch.

- Fuhrmann, Wolfgang (1 January 2007). "Pierre de la Rues Trauermotetten und die Quis dabit-Tradition". Tod in Musik und Kultur: 189–244. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- Weaver, Andrew H. (25 September 2020). A Companion to Music at the Habsburg Courts in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-43503-2. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

Tapestries

- Campbell, Thomas P.; Ainsworth, Maryan Wynn; N.Y.), Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York (2002). Tapestry in the Renaissance: Art and Magnificence. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-022-6. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- Delmarcel, Guy (1999). Flemish Tapestry from the 15th to the 18th Century. Lannoo Uitgeverij. ISBN 978-90-209-3886-9. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- Delmarcel, Guy (2000). Los Honores: Flemish Tapestries for the Emperor Charles V. Pandora. ISBN 978-90-5325-197-3.

- Horn, Hendrik J. (1989). Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen, Painter of Charles V and His Conquest of Tunis: Paintings, Etchings, Drawings, Cartoons & Tapestries. Davaco. ISBN 978-90-70288-25-9. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- Ortiz, Antonio Domínguez; Carretero, Concha Herrero; Godoy, José-A. (1991). Resplendence of the Spanish Monarchy: Renaissance Tapestries and Armor from the Patrimonio Nacional. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-621-4. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

Visual arts

- Gregg, Ryan E. (10 December 2018). City Views in the Habsburg and Medici Courts: Depictions of Rhetoric and Rule in the Sixteenth Century. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-38616-7. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- Kren, Thomas; McKendrick, Scot (1 July 2003). Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-704-7. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- Rosenthal, Earl E. (1985). The Palace of Charles V in Granada. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04034-9. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- Silver, Larry (2008). Marketing Maximilian: The Visual Ideology of a Holy Roman Emperor. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13019-4. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

Miscellaneous

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh Redwald (1976). Princes and Artists: Patronage and Ideology at Four Habsburg Courts, 1517-1633. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-014362-6. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

Remove ads

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads