Cuban exile

Person has been exiled from Cuba From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A Cuban exile is a person who has been exiled from Cuba. Many Cuban exiles have various differing experiences as emigrants depending on when they emigrated from Cuba, and why they emigrated.[1]

This article is missing information about experiences and communities of exiles. (January 2021) |

The exile of Cubans has been a dominating factor in Cuban history since the early independence struggles, in which various average Cubans and political leaders spent long periods of time in exile. Long since independence struggles, Miami has become the more center of residence for exilic Cubans, and a cultural hub of Cuban life outside of Cuba.[2] Miami became a center for Cuban emigrants, during the 1960s, because of a growing Cuban-owned business community which was supportive of recently arrived Cubans.[3]

History

Summarize

Perspective

This section is missing information about larger history of exiles from Cuba. (April 2025) |

Exile in Key West

1869 marked the beginning of one of the most significant periods of emigration from Cuba to the United States, centered on Key West. The exodus of hundreds of workers and businessmen was linked to the manufacture of tobacco. The reasons are many: the introduction of more modern techniques of elaboration of snuff, the most direct access to its main market, the United States, the uncertainty about the future of the island, which had suffered years of economic, political and social unrest during the beginning of the Ten Years' War against Spanish rule. It was an exodus of skilled workers, precisely the class in the island that had succeeded in establishing a free labor sector amid a slave economy.[4]

The San Carlos Institute was established on November 11, 1871 by members of the Cuban exile community who had taken refuge in Key West during the Ten Years' War (1868-1878). The effort was spearheaded by two prominent leaders of the exile community, Juan María Reyes and José Dolores Poyo, with the goal of creating a Cuban heritage and community center that would serve as host to cultural events, political meetings, and educational endeavors.[5][6][7]

Key West's subsequent rise in Cigar manufacturing and relocation of factories from Cuba was largely destroyed in Key West's devastating fire of April 1, 1886,[8] Hundreds of homes and several cigar factories were destroyed, including cigar mogul Vicente Martinez Ybor's still-operational main location. Needing jobs and not willing to wait for their homes and workplaces to be rebuilt, many Cuban tabaqueros decided to pack up their surviving belongings and board a steamship for Tampa.[9][10]

Ybor City and war of independence

More available jobs in the cigar industry attracted more residents to Tampa. Cigar workers found ready employment in the ever-growing number of large factories and small storefront shops ("buckeyes") and came in ever-growing numbers. More immigration meant more amenities such as a wider range of businesses and more opportunities for social and cultural events, which in turn attracted more new residents, which attracted more businesses, etc. This cycle of growth lasted for decades (into the late 1920s), by which time Ybor City was home to hundreds of cigar making businesses and tens of thousands of permanent residents and had a thriving cultural scene.[11]

Following the Ten Years' War, the Spanish authorities decided to exile pro-indepence writer Jose Marti to Spain.[12] Years later, on 26 November 1891, Jose Marti was invited by the Club Ignacio Agramonte, an organization founded by Cuban immigrants in Ybor City, Tampa, Florida, to a celebration to collect funding for the cause of Cuban independence. There he gave a lecture known as "Con Todos, y para el Bien de Todos", which was reprinted in Spanish language newspapers and periodicals across the United States. The following night, another lecture, " Los Pinos Nuevos", was given by Martí in another Tampa gathering in honor of the medical students killed in Cuba in 1871. In November artist Herman Norman painted a portrait of José Martí.[13]

On 5 January 1892, Martí participated in a reunion of the emigration representatives, in Cayo Hueso (Key West), the Cuban community where the Bases del Partido Revolucionario (Basis of the Cuban Revolutionary Party) was passed. He began the process of organizing the newly formed party. To raise support and collect funding for the independence movement, he visited tobacco factories, where he gave speeches to the workers and united them in the cause. In March 1892 the first edition of the Patria newspaper, related to the Cuban Revolutionary Party, was published, funded and directed by Martí. During Martí's Key West years, his secretary was Dolores Castellanos (1870–1948), a Cuban-American woman born in Key West, who also served as president of the Protectoras de la Patria: Club Político de Cubanas, a Cuban women's political club in support of Martí's cause, and for whom Martí wrote a poem.[14]

On 8 April 1892, Jose Marti was elected delegate of the Cuban Revolutionary Party by the Cayo Hueso Club in Tampa and New York. From July to September 1892 he traveled through Florida, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Jamaica on an organization mission among the exiled Cubans. On this mission, Martí made numerous speeches and visited various tobacco factories. In 1893, Martí traveled through the United States, Central America and the West Indies, visiting different Cuban clubs. His visits were received with a growing enthusiasm and raised badly needed funds for the revolutionary cause.[15]

Exile of the Moncada attackers

On March 10, 1952 all Cuban military garrisons came under coupist military command without resistance. The rebel officers occupied the University of Havana and opposition newspaper offices. Labor leaders were arrested and a communication black out ensued. A military junta formed in Camp Columbia with Fulgencio Batista as its head and declared itself the new government of Cuba.[16]

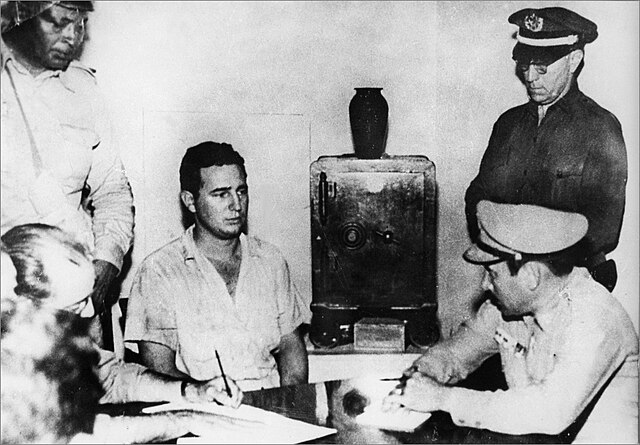

In 1953, Fidel Castro gathered 160 fighters and planned a multi-pronged attack on two military installations, in an effort to overthrow Batista's government.[17] On 26 July 1953, the rebels attacked the Moncada Barracks in Santiago and the barracks in Bayamo, only to be defeated decisively by the far more numerous government soldiers.[18]

Numerous important revolutionaries, including the Castro brothers, were captured soon afterwards.[19] Fidel was sentenced to 15 years in the prison Presidio Modelo, located on Isla de Pinos, while Raúl was sentenced to 13 years.[20] However, in 1955, yielding to political considerations, the Batista government freed all political prisoners in Cuba, including the Moncada attackers. Fidel's Jesuit childhood teachers succeeded in persuading Batista to include Fidel and Raúl in the release. Fidel Castro left Cuba for exile in Mexico.[21]

Golden exile and Pedro Pan

After the 1959 Cuban Revolution a mainly upper and middle class cohort of the emigrants began to leave Cuba. After the success of the revolution various Cubans who had allied themselves or worked with the overthrown Batista regime fled the country. Later as the Fidel Castro government began nationalizing industries many Cuban professionals would flee the island. This exodus would end after the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, when afterwards all travel out of Cuba was restricted. From 1959 to the end of open travel in 1962 around 250,000 Cubans left the island.[22]

During this exodus a secretive program known as the Cuban Children's Program was in operation, and helped unaccompanied children emigrate from Cuba. In February 1962, the newspaper The Plain Dealer detailed to its readers the masses of unaccompanied Cuban minors who made their way across the country for three years unnoticed. On March 9 of the same year, the Miami Herald's Gene Miller also ran a story about the event, in which he coined the term Operation Pedro Pan.[23]

Demographics

Summarize

Perspective

Social class

Cuban exiles would come from various economic backgrounds, usually reflecting the emigration wave they were a part of. Many of the Cubans who would emigrate early were from the middle and upper class, but often brought very little with them when leaving Cuba. Small Cuban communities were formed in Miami, the United States, Spain, Costa Rica, Uruguay, Italy, Canada, and Mexico. By the Freedom Flights, many emigrants were middle class or blue-collar workers, due to the Cuban government's restrictions on the emigration of skilled workers. Many exiled professionals were unlicensed outside Cuba and began to offer their services in the informal economy. Cuban exiles also used Spanish language skills to open import-export businesses tied to Latin America. By the 1980s many businesses owned by Cuban exiles would prosper and develop a thriving business community. The 1980 Mariel boatlift saw new emigrants from Cuba leaving the harsh prospects of the Cuban economy.[24]

Queer Cubans

Between 1965 and 1968, the Cuban government interned LGBTQ Cubans, along with others deemed deviant who would not or were not allowed to serve in military, into labor camps called the Military Units to Aid Production. Outside the labor camps, there would be prevalent discrimination and prejudiced ideation against LGBT members of Cuban society, and homosexuality would not be decriminalized until 1979. LGBTQ Cubans notably tried to escape the island either by enlisting in the Cuban military to be deployed abroad, or by emigrating in the Mariel boatlift where LGBTQ Cuban prisoners were specifically targeted by authorities to be given approval to emigrate.[25]

The male exiles of the Mariel boatlift were depicted by the Castro administration as effeminate and often pejoratively addressed with homophobia by leaders. Revolutionary masculinity (machismo) and an association of homosexuality with capitalism had fostered homophobic sentiments in Revolutionary Cuban culture. This atmosphere had driven many LGBTQ Cubans to flee when Castro announced he would allow the exodus. By 1980 homosexuality was no longer criminalized by Cuban law, but queer Cubans still faced systemic discrimination. There was a social phenomenon of straight men pretending to be gay to pass the interviews required of applicants for the exodus, because it was believed that homosexuals were more likely to pass the panel held to determine if a person could exit from Cuba. Communities of gay exiles formed in the processing centers that formed for those applying for entry to the United States. These centers kept their gender populations segregated. As a result[clarification needed], a majority of reports of LGBTQ Cuban Exile communities in these centers were focused on gay male exiles. However, secondhand reports suggested parallel lesbian communities had formed in the women's population. Though United States law technically barred emigration into the country on grounds of homosexuality, exceptions were made for the exiles to support them as anti-communists. Only LGBTQ people who clearly and explicitly told the US immigration panel that they identified as such were denied entry to the United States.[26]

Author Susana Pena has written about LGBTQ people in the Mariel boatlift and has speculated that their resettlement in Miami may have spurred on a revival of LGBTQ social life in Miami's South Beach.[27]

Afro-Cubans

While fewer Afro-Cuban exiles arrived in the earlier waves of migration, Afro-Cuban presence was larger among the Mariel Boatlift and Balseros periods. Anywhere between 20% and 40% of Marielitos were identified as black. A substantial portion of Afro-Cuban exiles assimilated into the African American community, but some remain active in the Cuban-American community.[28]

References

Bibliography

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.