Colombian Constitution of 1886

Founding constitution of the Republic of Colombia From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Colombian Constitution of 1886 was the constitution that remade the United States of Colombia into the Republic of Colombia, and replaced the federal republic with a unitary state. Following the Colombian Civil War (1884–1885), a coalition of moderate Liberals and Conservatives, led by Rafael Nuñez, ended the political period known as "the Radical Olympus", repealed the Constitution of Rionegro (1863), and substituted it with the constitution of 1886. From then on, the country was officially known as the Republic of Colombia. The Constitution of 1886 was the longest lasting constitution in the history of Colombia, eventually being itself replaced by the Constitution of 1991.

| Colombian Constitution of 1886 | |

|---|---|

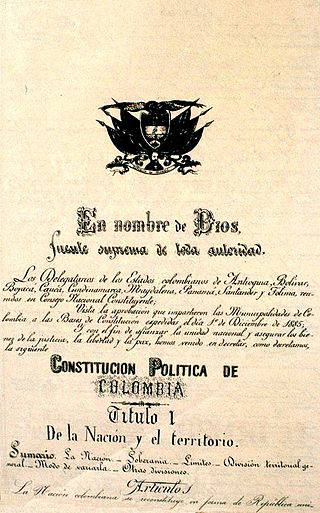

Page one of the original copy of the Constitution | |

| Ratified | August 4, 1886 |

| Author(s) | Delegates of the Consejo Nacional (National Council) |

| Signatories | Two delegates per state (18 total), one delegate member of the Conservative party and one delegate from the Liberal Party with moderate tendencies. Liberal radicals were excluded. |

| Purpose | National constitution to replace the Constitution of Rionegro |

Constituent Assembly

Summarize

Perspective

The Constituent Assembly consisted of 18 delegates, two from each of the nine states.

Rafael Núñez announced a national regeneration program and changed the country from a decentralized federal system to a centralized system with a strong central presidency. The presidential term was changed from two to six years. The president of the Republic was elected by the Congress. The president of each state was retitled governor. Governors were to be appointed by the president of the Republic. The governor would choose the mayors of his department, except the mayor of Bogotá, who was chosen by the president himself. Thus, the president in effect had control of the executive at all levels.

In addition, reelection of the president was authorized.

The chamber, the departmental assemblies, and the municipal councils were chosen by popular vote. The Senate was chosen by the departmental assemblies. The suffrage for elections of national scope was limited: men must be at least 21 or older and literate. However, illiterate men could vote in regional elections.

The position of vice-president was reinstated and was initially occupied by Eliseo Payán.

The Catholic religion became the official religion. In 1887, President Núñez made a concordat with the Vatican, reinstating powers to the Catholic Church that they had lost in the previous constitution.

This method of implementing constitutional changes based on the partisan wind of the moment, without having to be the result of agreement by the different political parties or the will of the people, was one of the causes of bipartisan polarization and violence in Colombia for many years. The population began to identify themselves more with the party concept than with the nation concept. The radical liberal segment was never reconciled to the loss of power and on three occasions, between 1885 and 1895, they tried to gain it by force. It took 44 years (up to 1930) for the Liberal party to regain power. The Constitution of 1886 remained effective for more than 100 years, guiding the mandate of 23 presidents of the Republic of Colombia, until 1991.

Separation of Panama 1903

In the Hay–Herrán Treaty, signed January 22, 1903, Colombia would have indefinitely rented a strip of land to the United States for the construction of a canal in the Department of Panama. Under this agreement, the United States would pay Colombia US$10 million and after nine years an annuity of $250,000 per year. The proposal was rejected by the Colombian Congress, who considered it disadvantageous to the country, not only because the payments would not last forever, but because conceding the isthmus indefinitely to a foreign country represented a loss of national sovereignty.

On November 3, 1903 Panama separated from Colombia with the direct support of the United States. On November 6, the United States recognized Panama's sovereignty and on November 11, the United States informed Colombia they would oppose Colombian troops if they attempted to recover Panama and backed the claim by sending warships to the isthmus. The Thousand Days' War, along with political disorganization in Bogotá, had left Colombia too weak to oppose the separation. On November 18, the United States signed the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty with Panama for the construction of the Panama Canal.

The Reform of 1905

In December 1904, a few months after being elected president, General Rafael Reyes shut down Congress because of its unwillingness to approve the reforms he desired. At the beginning of 1905, he summoned a National Constituent Assembly consisting of three representatives from each department, chosen by the departmental administrators.

The Assembly abolished the vice-presidency, two of the designaturas, and the State Council. It also specified that the magistrates of the Supreme Court of Justice would serve for life, recognized the right of representation for minorities, and the possibility of reforming the Constitution by means of a National Assembly.[1]

The National Assembly demonstrated its support for a government with a dictatorial character when it established a presidential period of 10 years for General Reyes (from January 1, 1905, to January 31, 1914), with the possibility of directly appointing his successor. If the new president were someone other that Reyes the term would be for four years.[1] However, General Reyes overthrown in 1909.

The Reform of 1910

Because of the unexpected overthrow of General Reyes on June 13, 1909, the Congress chose the former vice-president, conservative General Ramón González Valencia, to serve as Interim President of Colombia from August 3, 1909, to August 7, 1910.

In 1910, González summoned a National Assembly (elected through the municipal councils) to reform the Constitution of 1886, which started sessions on May 15. This important reform, inspired by the members of the Republican Union (a third political party with bipartisan principles of free elections and religious tolerance), banned the participation of the military in politics and established the direct popular election of the president, departmental assemblies and municipal council. It reduced the presidential period from 6 to 4 years, prohibited the immediate reelection of presidents, eliminated the figure of the vice-president and replaced it by one appointee that would be chosen by the Congress. It established a system of proportional representation for the appointment of members of public corporations according to votes obtained, assuring a minimum of one third for the opposition party. It granted the Congress the faculty to choose the magistrates of the Supreme Court of Justice, consecrating constitutional control of the Supreme Court of Justice. With these reforms the presidential powers were reduced.

Before this reform, the president was chosen by the electoral college that represented the electoral districts.

This reform kept in force the previous voter qualifications: literacy requirement and an annual rent of at least 300 pesos or possessing real estate with a value of at least 1,000 pesos.

The president retained the power to name governors who in turn would appoint mayors, corregidores, administrators, directors of post offices, heads of jails, managers of banks, and others.

It was not until August 27, 1932, during the government of Olaya Herrera, that the number of seats in Congress was regulated with Law no. 7. This new law set the number of seats for each party to be proportional to the number of votes obtained by each party, with a minimum of one-third of the seats for the opposition party. Guaranteeing one-third of the seats for the opposition had indirect undesired effects. During conservative governments, the liberal party boycotted the electoral process as a means of protest in several elections, knowing that in any case it would obtain one-third of the positions in Congress. On one occasion, not even the third party was accepted.

To begin the period of transition, on July 15, the Constituent National Assembly made an exception to the rule of popular election of presidents and elected the first president of the Republican Union, Carlos Eugenio Restrepo, and also chose the first and second designates.

The Reform of 1936

On August 1, 1936, during the government of Alfonso López Pumarejo, the Congress made several reforms. Illiterate men could now vote. This rule was implemented for the first time in the presidential election of 1938, which the liberal Eduardo Santos won.

Although they were not considered citizens for the purposes of suffrage, women were granted the right to occupy most public positions and began to attend university. Control of the Catholic Church over education started to wane.

The Reform of 1954

During the government of Gustavo Rojas Pinilla and by his suggestion, the National Constituent Assembly (Asamblea Nacional Constituyente, ANAC) unanimously recognized the political rights of women by means of the Legislative Act No. 3 of August 25, 1954. Women exerted this right for the first time during the plebiscite of December 1, 1957, to approve the constitutional change that would allow both traditional political parties, Liberal and Conservative, to govern together as the National Front.

Three attempts to recognize the right of women to vote had failed. The first attempt was in, in 1934, during the government of Alfonso López Pumarejo, a law was presented to the Congress failed to pass. Voting rights for women did not appear in the constitutional reform of that year. The second attempt was the proposal presented by liberal Alberto Lleras Camargo in 1944; it was postponed under the excuse that this regulation could not be approved before 1948. The third attempt was the proposal presented by the liberal Alfonso Romero Aguirre in 1948, which was slated to be implemented in a gradual fashion, but it was really another postponement.

The Reform of 1957

In October 1957, the temporary Military Junta that succeeded Rojas Pinilla authorized with the agreement of the traditional political parties constitutional reform by means of the Legislative Act No. 0247. This legislation fixed the parity of the parties with the stated purpose of finding a solution to the problems of the country. This agreement and the corresponding period was called National Front.

The plebiscite of December 1, 1957, approved, with almost 94% of votes cast, the constitutional reform giving parity to both traditional parties in control of public corporations for a term of 12 years. It was determined that the elections for President of the Republic, Congress, departmental assemblies, and municipal councils would take place in the first half of 1958.

The Reform of 1958

The first Congress elected by popular means within the National Front made a constitutional change to extend the term of the National Front from 12 to 16 years and decided that the first president would be Liberal, not Conservative as had been agreed before.

The Reform of 1968

Although the National Front ended in 1974, the constitutional reforms preparing for the transition began in 1968 during the government of Carlos Lleras Restrepo, the next to last President of the National Front.

With the purpose of regulating the electoral competition between parties, the reforms eliminated the distribution by halves for departmental assemblies and municipal councils. Also included were some measures to recognize minority parties. Some required reforms were postponed, in some cases indefinitely, such as the ordinal one of article 120 of the Constitution granting "the right and fair participation of the second party in voting." Article 120 had the unintended effect of limiting the participation of minority parties and therefore limiting citizen participation. It established that later reforms to the constitution could be made by the Congress, as long as the reform was approved by two-thirds majority of the members of the Senate and the in camera voting of two consecutive ordinary legislative sessions.

The Reform of 1984

On November 21, 1984, during the government of Belisario Betancur, the Congress established popular voting for mayors and governors, with the aim of reducing or eliminating central control of the parties over nominations and of improving regional democracy.

See also

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.