Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Head covering for Christian women

Practice of female head covering in Christianity From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Christian head covering, also known as Christian veiling, is the traditional practice of women covering their head in a variety of Christian denominations. Some Christian women wear the head covering in public worship and during private prayer at home,[1][2][3] while others (particularly Conservative Anabaptists) believe women should wear head coverings at all times.[4] Many theologians of the Oriental and Eastern Orthodox Churches likewise teach that it is "expected of all women to be covered not only during liturgical periods of prayer, but at all times, for this was their honor and sign of authority given by our Lord",[5] while others have held that headcovering should at least be done during prayer and worship.[6][7] Genesis 24:65[8] records the veil as a feminine emblem of modesty.[9][10]

Manuals of early Christianity, including the Didascalia Apostolorum and Pædagogus, instructed that a headcovering must be worn by women during prayer and worship as well as when outside the home.[11][12] When Paul the Apostle commanded women to be veiled in 1 Corinthians, the surrounding pagan Greek women did not wear head coverings; as such, the practice of Christian headcovering was countercultural in the Apostolic Era, being a biblical ordinance rather than a cultural tradition.[A][17][18][19] The style of headcovering varies by region, though Apostolic Tradition specifies an "opaque cloth, not with a veil of thin linen".[20]

Those enjoining the practice of head covering for Christian women while "praying and prophesying" ground their argument in 1 Corinthians 11:2–16.[21][22] Denominations that teach that women should wear head coverings at all times additionally base this doctrine on Paul's dictum that Christians are to "pray without ceasing" (1 Thessalonians 5:17),[23][24] Paul's teaching that women being unveiled is dishonourable, and as a reflection of the created order.[B][24][32][33] The consensus of Biblical scholars conclude that in 1 Corinthians 11 "verses 4–7 refer to a literal veil or covering of cloth" for "praying and prophesying" and hold verse 15 to refer to the hair of a woman given to her by nature.[34][35][36][37][38] Christian headcovering with a cloth veil was the practice of the early Church, being universally taught by the Church Fathers and practiced by Christian women throughout history,[34][2][39][40] continuing to be the ordinary practice among Christians in many parts of the world, such as Romania, Russia, Ukraine, Egypt, Ethiopia, India and Pakistan;[41][42][43][44] additionally, among Conservative Anabaptists such as the Conservative Mennonite churches and the Dunkard Brethren Church, headcovering is counted as an ordinance of the Church, being worn throughout the day by women.[4][30] However, in much of the Western world the practice of head covering declined during the 20th century and in churches where it is not practiced, veiling as described in 1 Corinthians 11 is usually taught as being a societal practice for the age in which the passage was written.[45][46]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Scriptural and Second Temple background

During the time of Moses, the Bible records that it was normative for women to wear a head covering (compare with: Numbers 5:18).[47][48] In Numbers 5:18, the sotah (meaning "one who goes astray") ritual, in which the head of a woman accused of adultery is uncovered (made parua), is explicated, implying that normally a woman's head is covered; the Talmud thus teaches that the Torah (Pentateuch) commands women to go out in public with their heads covered.[49][50] This head covering worn during biblical times was a veil or headscarf.[51]

In the Old Testament's Book of Daniel, Susanna wore a head covering and wicked men demanded that it be removed so that they might lust after her (cf. Susanna 13:31–33).[52] Genesis 24:64–65 records that Rebecca, while traveling to meet Isaac, covered her head for modesty, demonstrating "her sense of propriety on meeting her betrothed."[53] The removal of a woman's veil in the passage of Isaiah 47:1–3 is linked with nakedness and shame.[54] The biblical book Song of Songs records "the erotic nature of hair from the verse, 'Your hair is as a flock of goats' (Song of Songs, 4:1), i.e., from a verse praising her beauty."[55] Jewish law around the time of Jesus stipulated that a married woman who uncovered her hair in public evidenced her infidelity.[56]

Apostolic period (1st century)

Paul first established the Christian community in Corinth around 51–52 AD after arriving from Athens.[57] The church was culturally mixed, composed mostly of Gentiles with some Jewish presence.[58]

During his extended stay in Ephesus (ca. 53–55 AD), Paul received reports of divisions and disorder in the Corinthian church. In response he wrote 1 Corinthians, probably in the spring before Pentecost,[59] and sent it from Ephesus by trusted messengers in the late winter or early spring of 56 AD.[60] In his greeting Paul calls them "the church of God" in Corinth but also includes "all who in every place call on the name of Jesus Christ," showing that his directives, such as on worship and head covering, were framed for the wider Christian audience (cf. Christendom).[61][62]

Between 1 Corinthians and 2 Corinthians, Paul made what is known as the "painful" visit to Corinth, which left both sides distressed, and then sent a severe letter now lost.[63] According to 2 Corinthians, Titus later reported that Paul's rebuke produced "godly sorrow," leading the Corinthians to repent and show renewed zeal and loyalty. Paul expressed consolation at this change and even boasted of their readiness to believers in Macedonia, using their example to stir generosity. The letter is also addressed to "all the holy people in the whole of Achaia," and Collins suggests that Christians from other towns in the province may have joined the Corinthian assembly at times, indicating that practices circulated regionally.[64] In 1 Corinthians 11, Paul notes that the wearing of the head covering by women was a feature of all Christian churches throughout the known world.[65][66]

Patristic period (2nd–5th centuries)

Early Christian writers broadly wrote on the practice of women's head coverings, teaching that Paul's instructions (1 Cor 11:2–16) applied to both prayer and daily dress. Taken together, these sources present a largely unified patristic expectation that modest Christian women cover their heads not only in worship but in ordinary life. Many scholars infer that, as Christianity gained imperial standing in the fourth century, such clerical ideals increasingly shaped social practice.[67] Some of the reasons by the Church Fathers for covering include: associating a woman's hair with erotic allure; arguing that women should assume the veil at puberty; treating it as integral to women's attire; and appealing to "natural law".[68][67][69]

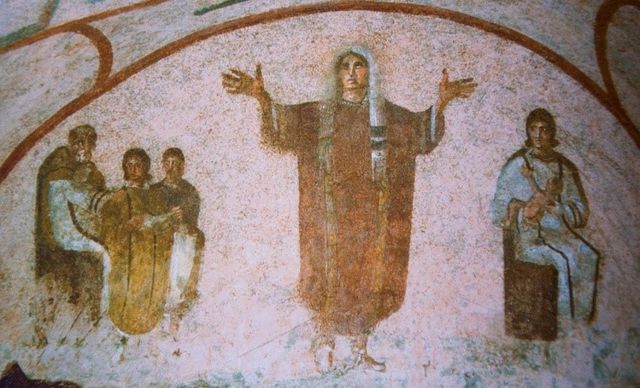

Early Christian art and architecture indicate that women prayed with cloth veils on their heads; catacomb depictions from the second and third centuries show women praying with head coverings.[70][71]

2nd century

Starting in the second century, Irenaeus (c. 125 – c. 202) treats 1 Corinthians 11:10 as authentic apostolic instruction tied to women's prophecy. In Against Heresies 3.11.9 he defends Paul's witness to prophetic gifts "of men and women" in the church, implying that the Pauline regulation on women's head coverings applied in worship.[72]

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 215), an early Christian theologian, instructed in Paedagogus (written in Egypt c. 190) that women should be fully covered in public and may uncover only at home. He presents this dress as sober and protective against public gaze, argues that modest veiling prevents both personal lapse and provoking others to sin, and states that women ought to pray veiled as fitting the will of the Word.[73]

3rd century

Into the third century, Tertullian (c. 155 – c. 220) in De virginibus velandis addresses a Carthaginian dispute in which virgins, that is, unmarried females who have reached puberty, appeared in church unveiled. Citing 1 Corinthians, some argued that Paul's veiling rule bound only "wives," not virgins. Tertullian replies on three grounds. First through custom: the practice of the major, apostolic churches is veiling; going unveiled is immodest and disrupts ecclesial unity. Second by definition: "woman" is a single gender embracing virgins, widows, and wives; Eve before marriage and Mary (explicitly called "woman") show that virgins are still women. Thirdly by nature and lineage: long hair, cosmetics, and the veil are "testimonies of the body" marking a shared female nature, linked to Eve's transgression and the "daughters of men" narrative; the veil signifies penance and restrains seduction. He reframes the debate from bodily practice to scriptural argument, claims unveiling compromises virginity, and bases the issue in church order: if virgins formed a separate gender they might claim teaching or baptizing. Since they do not perform male functions, they share the same genus as matrons and must remain veiled.[75]

Hippolytus of Rome (c. 170 – c. 235) while giving instructions for church gatherings said "... let all the women have their heads covered with an opaque cloth, not with a veil of thin linen, for this is not a true covering."[76]

The apocryphal Acts of Thomas (c. before 240),[77] preserved in both Greek and Syriac versions, includes a "tour of hell" section describing punishments for various sins. In the Greek version, the narrator reports that "those that are hung by the hair are the shameless who have no modesty at all and go about in the world bareheaded."[78]

4th and 5th century

Diodorus of Tarsus (c. ? – c. 390), a theologian, states a man is "image and glory of God" and therefore prays with head uncovered, while a woman is "the glory of man" and is veiled. He infers that the veiled one is not the image of God in the same sense as the man, though she is consubstantial with him. He therefore links "image" to the exercise of authority or rule, grounding it in Genesis 1:28 (dominion over creatures). Thus, the veil signifies differentiated authority, namely that male headship is bearer of the image qua rule, and female glory as related to the man.[79]

John Chrysostom (c. 347 – c. 407) held that to be disobedient to the Christian teaching on veiling was harmful and sinful, stating: "... the business of whether to cover one's head was legislated by nature. When I say 'nature', I mean 'God'. For he is the one who created nature. Take note, therefore, what great harm comes from overturning these boundaries! And don't tell me that this is a small sin."[80]

Jerome (c. 342 – c. 347 – 420) noted that the hair cap and the prayer veil is worn by Christian women in Egypt and Syria, who "do not go about with heads uncovered in defiance of the apostle's command, for they wear a close-fitting cap and a veil."[81]

Augustine of Hippo (354–430) writes about the head covering, "It is not becoming, even in married women, to uncover their hair, since the apostle commands women to keep their heads covered."[82]

Medieval period (5th–15th centuries)

By the Middle Ages, going bareheaded carried strong stigma; in southern Italy, uncovered women were visually coded as adulteresses or prostitutes.[83] Across Byzantium and medieval Europe, long female hair was linked with seduction and immodesty, prompting the expectation that women conceal it under veils, hoods, or caps; only virgins could appear publicly with uncovered hair.[84]

Artistic and legal evidence reflects this norm with medieval art depicting veiled women in worship, and sumptuary laws regulated the quality and expense of women's veils as a matter of modesty and social order.[85]

Theologians such as Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) stated: "they erred in clothing, namely, because the women gathered for the sacred mysteries with heads uncovered; (§586)."[86]

Modern period (16th–21st centuries)

Until at least the 19th century and still extant in certain regions, the wearing of a head covering, both in the public and while attending church, was regarded as customary for Christian women, in line with the injunction to do so in 1 Corinthians 11, in the Mediterranean, European, Indian, Middle Eastern, and African societies.[87][88][89][90][91]

16th and 17th century

In early modern and modern interpretation, 1 Corinthians 11 was often read in tandem with 1 Timothy 2 and 1 Corinthians 14.[92]

John Calvin, who saw the wearing of head coverings by Christian women as normative, subsumed 1 Corinthians 11 under the admonition to silence: the veil addresses women who presume to speak, but it does not license them to do so; in the Institutes he treats veiling "within a larger context of understanding the common good".[92]

The Council of Trent (1545–1563), convened by Pope Paul III, responded to the Protestant Reformation by clarifying Catholic doctrine and tightening church discipline. Within post-Tridentine Catholicism, women in religious life were distinguished by their religious habit and the rite of profession was commonly described as "taking the veil."[93]

Cornelius à Lapide (1567–1637), a Jesuit priest, argued in his commentary that Paul's passage on head coverings was intended to distinguish Christian practice from pagan custom. He contended that the Apostle sought to abolish the "heathen" practice where women worshipped "bareheaded, according to the ancient custom of the heathen."[94]

The 1599 Geneva Bible's commentary adds that a woman uncovered in public worship "shame[s] themselves," removing "the sign and token of their subjection," and appeals to "nature" (women’s long hair) to judge appearing bareheaded improper.[95]

Philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) says women at Corinth sometimes "prayed and prophesied" in assembly, but had to remain veiled while doing so. He adds that ordinary speaking in church was to be silent for women "without an extraordinary call," whereas speaking was allowed when it was "by an extraordinary call and commission from God," i.e., by the Spirit’s "immediate motion and impulse."[96][92]

In the 1600s Christian literature, with respect to demonology, has documented that during exorcisms, possessed women have attempted to tear off their headcovering, as with the case of Frances Bruchmüllerin in Sulzbach.[97][98] These instances are tied by some to the enigmatic phrase "because of the angels" in 1 Corinthians 11:10, in which a veiled head is seen as a shield against attacks by fallen angels such as those mentioned in the Book of Enoch.[99]

18th and 19th century

Across much of 18th-century Europe, women were widely expected to cover their heads in public and at worship.[100] the practice was often read through 1 Corinthians 11 as signaling female subordination, and bare-headed women could face exclusion or harassment.[101] In Spain the lace mantilla had, by around 1800, become a potent marker of Spanish female identity,[102] while in Venice veiling and masking practices formed part of urban decorum into the long eighteenth century.[103]

Victorian periodicals registered resistance to strict covering norms; for example, The Christian Lady’s Magazine (1855) criticized coiffures and gauzy hats that left hair visible, extending its critique from church to public life.[104]

Many Protestant exegesis held Paul's injunctions as being normative to public Christian worship: H. A. W. Meyer treated covering as a congregational, custom-shaped matter, and Frédéric Godet argued that if a woman appeared prominently (e.g., under exceptional inspiration), the veil should all the more signal modesty.[105]

By the late Victorian period, resistance was more open: Elizabeth Cady Stanton recounted a London church incident in which a woman chose to stay away rather than resume wearing a bonnet after a reprimand.[106] A feminist interpreter similarly sought to limit the passage's normativity by challenging Pauline authorship or transmission: in The Woman's Bible (1895–98), Lucy Stone questioned the authority of Paul's injunctions on women's veiling, attributing them not to divine command but to "an old Jewish or Hebrew legend" that Paul, educated "at the feet of Gamaliel," merely repeated. She thus treated the mandate as culturally derived rather than binding. Stanton treated the veiling as a token of subjection.[105]

Influential 18th–19th-century commentators generally upheld head covering as a normative Christian practice for women.[107][108][109] This position is seen in works such as: as Matthew Henry's Bible Commentary (1706),[110] Charles Hodge's An Exposition of the First Epistle to the Corinthians (1874),[111] Frédéric Louis Godet's Commentary on First Corinthians (1886),[112] Heinrich Meyer's Critical and Exegetical Handbook to the Epistles to the Corinthians (1884),[113] John Gill's Exposition of the New Testament: 1 Corinthians (1746–1748),[114] Henry Alford's The Greek Testament (1857–1861),[115] and Thomas Charles Edwards's A Commentary on the First Epistle to the Corinthians (1885).[116]

20th century

In the early part of the 20th century in Britain, wearing a hat was widely treated as integral to women’s public dress and going out bareheaded could be seen as a breach of propriety.[117] Throughout the nineteenth century hats functioned as a cultural necessity in many contexts and that, up to World War I, many women donned a white cap upon rising and wore a hat or bonnet outside the home.[118][119]

From the sixteenth to the early twentieth century, Catholic discipline on women’s attire in worship remained stringent.[120] In 1904, Pope Pius X initiated a comprehensive codification of canon law that culminated in the 1917 Code of Canon Law (promulgated by Benedict XV; in force from 1918), which codified long-standing practice rather than introducing a novel obligation.[120]

In regions such as the Mediterranean and the Middle East, many Christian women continued (and in some places continue) to cover in public or at worship;[121] in Ethiopia (netsela);[122] and in the Indian subcontinent head covering as a sign of respect spans Hindu, Sikh, Muslim, and Christian communities.[123] However, over the course of the early–mid twentieth century, the practice declined in much of the West; some writers link Western reinterpretations that do not require veiling with broader social changes associated with second-wave feminism.[124][125] In 1968, the National Organization for Women adopted a "Resolution on Head Coverings":[126][127]

WHEREAS, the wearing of a head covering by women at religious services is a custom in many churches and whereas it is a symbol of subjection within these churches, NOW recommends that all chapters undertake an effort to have all women participate in a "national unveiling" by sending their head coverings to the task force chairman immediately. At the Spring meeting of the Task force on Women in Religion, these veils will then publicly be burned to protest the second class status of women in all churches.

In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1969, fifteen women from the Milwaukee chapter of NOW protested in St. John de Nepomuc Catholic Church; after taking their place at the communion rail, the women removed their hats and placed them on the communion rail.[128] The following week, the Milwaukee Sentinel published a letter to the editor from "Mrs. M. E., Milwaukee," who called the protest "immature exhibitionism."[126][129] Academic publications have noted that the decline of head coverings in many churches correlates with second-wave feminism and with efforts by organizations like NOW to engage religious institutions.[124]

In the mid-20th century, some scholarship began to read 1 Corinthians 11:3–16 as culturally specific.[130] For example, Pierce, Groothuis, and Fee argue that the covering and its social meaning were context-bound in Corinth and that today the practice is a matter of personal choice rather than universal mandate.[131] William O. Walker Jr. advances an interpolation view of 1 Cor 14:34–35.[132] William Barclay reads 1 Cor 11 with reference to Near Eastern head-covering customs.[132] J. Murphy-O’Connor and A. C. Thiselton construe the passage as marking gender differentiation rather than prescribing a timeless dress law.[133] Hans Conzelmann argues local convention and cautions against universalizing Paul’s rationale.[134] Social-anthropological and cultural-history approaches (e.g., Judith Gundry-Volf; Dale B. Martin) situate the text within Mediterranean honor/shame codes and ancient medical cosmology, interpreting veiling as a practice guarding social and bodily order.[135]

In the Catholic Church, the 1983 Code of Canon Law replaced the 1917 code in its entirety and contains no head-covering requirement; where the custom persists, it is by local practice rather than universal law.[136][137][138] Though the practice of head covering was normative in many Protestant churches (Lutheran, Continental Reformed, Presbyterian, Congregationalist, Anglican and Methodist) of the West prior to the 1960s, at present most evangelical churches in the West (apart from those of Conservative Anabaptism) give the practice little emphasis in informal worship.[139][140][130] A number of traditions retain the ordinance of head covering for women: Conservative Anabaptist denominations and Old Order Anabaptist groups (Mennonites, Amish, Hutterites) link 1 Corinthians 11 with 1 Thessalonians 5:17 and have women wear bonnets or white organza prayer caps throughout waking hours, with hair typically long, center-parted, and pinned up; Conservative Anabaptists more generally have retained women’s head coverings and uncut long hair, practices often abandoned by mainline Anabaptists.[130][141] Among the Amish, women typically wear long hair with a prayer covering (white for married women, black for unmarried girls) and add a bonnet and shawl in cold weather.[142] Certain African American congregations also preserve head-covering customs; for example, among Spiritual Baptists "women always tie their head" for worship, including in North American congregations.[143][144]

Since the 2010s, a subset of younger Catholics and Lutherans have revived veiling, in the former case often linked to renewed interest in the Traditional Latin Mass and framed as a voluntary sign of reverence, with clergy noting visible growth and vendors reporting increased sales.[145][146][147] Some nuns of the Catholic, Lutheran and Anglican traditions of Christianity still wear the covering as part of their religious habit.[148][149][150]

Remove ads

Styles

Summarize

Perspective

Early church

Dura-Europos, 3rd century

Aquileia Basilica, 4th century

Santa Maria Maggiore, Annunciation, 5th century

From the 1st century AD through Late Antiquity, Christian writers across major centers consistently described head coverings as substantial and opaque, though each region articulated the practice in distinct ways. Many dress/social-history scholars read these texts as norm-making rhetoric amid diverse local "micro-practices".[151][152] Certain scholars argue for a normative, socially enforced régime grounded in Paul's instructions in 1 Corinthians 11.[153][154][155]

Alexandria

Clement of Alexandria urges women to be "entirely covered" in worship, calls veiling "becoming" for prayer, and warns against conspicuous veils (e.g., purple) or uncovering that invites the gaze (Paedagogus III).[156][157]

Bethlehem

In Bethlehem, Jerome’s ascetic counsel links female with plain, enveloping dress and restrained deportment: in his letter to Eustochium he urges continuous modesty in public and private (e.g., staying indoors unless necessary, avoiding conspicuous attire, and practicing downcast bearing), and in his later exhortation to Demetrias he prefers simple, concealing garments over fine linen and showy dress.[158][159]

Carthage

Tertullian’s De virginibus velandis specifies a substantial head-covering, "as far as the place where the robe begins," with the "region of the veil… co-extensive with the space covered by the hair when unbound" and criticizes substitutes such as turbans, woollen bands, or small linen coifs that "do not reach… the ears."[160][161] Cyprian’s De habitu virginum likewise advocates modest dress and hair, discouraging braided hair and ornamental display, and warning against adornments that "hide the neck."[162]

Constantinople and Antioch

John Chrysostom reads 1 Corinthians 11 to require women’s head-covering as an ongoing practice rather than merely momentary in prayer. He describes the veil as one "carefully wrapped up on every side for complete enclosure," insisting it be worn continuously as a sign of modesty and order, not just in the liturgy.[163][164][165] He also links the external covering with modesty and order: "being covered is a mark of subjection and authority… [it] preserve[s] entire her proper virtue. For the virtue and honor of the governed is to abide in his obedience"). In a parallel vein, commenting on 1 Timothy 2:9, Chrysostom defines "modest apparel" as "such attire as covers [women] completely, and decently."[166]

Rome and Italy

The church order attributed to Hippolytus requires an "opaque cloth," not thin linen, "for this is not a true covering" (Apostolic Tradition II.18).[167] The Shepherd of Hermas depicts the Church "veiled up to her forehead" with a hood (Vision 2.4.1–2).[168][169] Ambrose exhorts consecrated women to cover their hair "take the cap which will cover your hair and conceal your countenance."[170]

Contemporary

Christina Lindholm (2012) observes that across Christian traditions, the veil or head covering has encompassed diverse garments, influenced by the culture in which the church is located. In Western Europe, the colour of the veil could mark certain occasions or states of life, such as white for brides or black for widows; religious orders used them as signs of consecration. Eastern Christians use scarves and wraps tied to modesty customs, and Anabaptists favor plain kapps as symbols of obedience. After World War II, hats and headscarves in Western churches declined but remain in use in some locales. Head coverings thus continue to adapt, carrying meanings of modesty, consecration, identity, and belonging.[171] For example, as Christianity expanded in India, converts often adopted religious practices mediated by local custom, including women's dress; where saris or shalwar kameez predominate, churchgoing attire commonly includes a head covering (e.g., dupatta or pallu).[172] In the present-day, various styles of head coverings are worn by Christian women including:

Remove ads

Denominational practices

Summarize

Perspective

Many women of various Christian denominations around the world continue to practice head covering during worship and while praying at home,[41][206] as well as when going out in public.[207][42][208] This is true especially in parts of the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, and Eastern Europe (such as Western Moldavia).[207][209][210][1][42][208]

Western Christianity

At the start of the 20th century, it was commonplace for women in mainstream Christian denominations of Western Christianity around the world to wear head coverings during church services.[211][91] These included Anabaptist,[212][213] Anglican,[214] Catholic,[215][216] Lutheran,[217] Methodist,[218] Moravian,[219] Plymouth Brethren,[220] Quaker,[221] and Reformed.[222] Those women who belong to Anabaptist traditions are especially known for wearing them throughout the day.[223][224]

Western women formerly wore bonnets as their head coverings, and later, hats became predominant.[225][226] This practice has generally declined in the Western world, though head coverings for women are common during formal services such as weddings, in the United Kingdom.[227][228][214] Among many adherents of Western Christian denominations in the Eastern Hemisphere (such as in the Indian subcontinent), head covering remains normative.[41][223][229][2]

Anabaptist

Many Anabaptist women, especially those of the Conservative Anabaptist and Old Order Anabaptist branches, wear head coverings, often in conjunction with plain dress.[230] This includes Mennonites (e.g., Old Order Mennonites and Conservative Mennonites), River Brethren (Old Order River Brethren and Calvary Holiness Church),[231] Hutterites,[232] Bruderhof,[212] Schwarzenau Brethren (Old Order Schwarzenau Brethren and Dunkard Brethren Church),[233] Amish, Apostolic Christians and Charity Christians.[234][235] Headcovering is among the seven ordinances of Conservative Mennonites, as with the Dunkard Brethren.[4][30]

Catholic

Headcovering for women was unanimously held by the Latin Church until the 1983 Code of Canon Law came into effect.[236] A headcovering in the Catholic tradition carries the status of a sacramental.[237][238] Historically, women were required to veil their heads when receiving the Eucharist following the Councils of Autun and Angers.[239] Similarly, in 585, the Synod of Auxerre (France) stated that women should wear a head-covering during the Holy Mass.[240][241] The Synod of Rome in 743 declared that "A woman praying in church without her head covered brings shame upon her head, according to the word of the Apostle",[242] a position later supported by Pope Nicholas I in 866, for church services."[243] In the Middle Ages, Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) said that "the man existing under God should not have a covering over his head to show that he is immediately subject to God; but the woman should wear a covering to show that besides God she is naturally subject to another."[244] In the 1917 Code of Canon Law it was a requirement that women cover their heads in church. It said, "women, however, shall have a covered head and be modestly dressed, especially when they approach the table of the Lord."[245] Veiling was not specifically addressed in the 1983 revision of the Code, which declared the 1917 Code abrogated.[246] According to the new Code, former law only has interpretive weight in norms that are repeated in the 1983 Code; all other norms are simply abrogated.[215] This effectively eliminated the former requirement for a headcovering for Catholic women, by silently dropping it in the new Code of Canon. In some countries, like India, the wearing of a headscarf by Catholic women remains the norm. The Eucharist has been refused to ladies who present themselves without a headcovering.[247]

Traditional Catholic and Plain Catholic women continue to practice headcovering, even while most Catholic women in western society no longer do so.[248]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

In 2019, veiling of women during part of the Church’s temple endowment ceremony was discontinued.[249] That same year, a letter from the Church's First Presidency stated that "Veiling an endowed woman's face prior to burial is optional." It had previously been required. The letter went on to say that such veiling, “may be done if the sister expressed such a desire while she was living. In cases where the wishes of the deceased sister on this matter are not known, her family should be consulted”.[249]

Lutheran

The General Rubrics of the Evangelical Lutheran Synodical Conference of North America, as contained in The Lutheran Liturgy, state in a section titled "Headgear for Women": "It is laudable custom, based upon a Scriptural injunction (1 Cor. 11:3–15), for women to wear an appropriate head covering in Church, especially at the time of divine service."[250] Some Lutheran women wear the headcovering during the celebration of the Divine Service and in private prayer.[251]

Martin Luther, the father of the Lutheran tradition, encouraged wives to wear a veil in public worship.[252] Lutheran systematic theologian Philip Melanchthon broadened this to the public square, holding that "a woman sins who goes in public without her head covered".[253]

Moravian/Hussite

The haube is a Christian headovering that has historically been worn by women who belong to the Moravian Church, at least since the 1730s.[254] Nicolaus Zinzendorf, a Moravian divine, "likened the Haube to a 'visible diadem' representative of Jesus' burial cloth." In 1815, Moravian women in the United States switched to wearing the English bonnet of their neighbors.[254] Certain Moravian women continue to wear a headcovering during worship, in keeping with 1 Corinthians 11:5–6.[255] Additionally, in the present-day, Moravian ladies wear a lace headcovering called a haube when serving as dieners in the celebration of lovefeasts.[256]

Reformed

In the Reformed tradition, both John Calvin, the founder of the Continental Reformed Churches, and John Knox, the founder of the Presbyterian Churches, both called for women to wear head coverings.[257][258] Calvin taught that headcovering was the cornerstone of modesty for Christian women and held that those who removed their veils from their hair would soon come to remove the clothing covering their breasts and that covering their midriffs, leading to societal indecency:[259]

So if women are thus permitted to have their heads uncovered and to show their hair, they will eventually be allowed to expose their entire breasts, and they will come to make their exhibitions as if it were a tavern show; they will become so brazen that modesty and shame will be no more; in short they will forget the duty of nature...Further, we know that the world takes everything to its own advantage. So, if one has liberty in lesser things, why not do the same with this the same way as with that? And in making such comparisons they will make such a mess that there will be utter chaos. So, when it is permissible for the women to uncover their heads, one will say, 'Well, what harm in uncovering the stomach also?' And then after that one will plead for something else; 'Now if the women go bareheaded, why not also bare this and bare that?' Then the men, for their part, will break loose too. In short, there will be no decency left, unless people contain themselves and respect what is proper and fitting, so as not to go headlong overboard.[260]

Furthermore, Calvin stated "Should any one now object, that her hair is enough, as being a natural covering, Paul says that it is not, for it is such a covering as requires another thing to be made use of for covering it."[259] Other Reformed supporters of headcovering include: William Greenhill, William Gouge, John Lightfoot, Thomas Manton, Christopher Love, John Bunyan, John Cotton, Ezekiel Hopkins, David Dickson, and James Durham.[261]

Other Reformed figures of the 16th and 17th centuries held that head covering was a cultural institution, including William Perkins,[262] Walter Travers,[263] William Ames,[264] Nicholas Byfield,[265] Arthur Hildersham,[266] Giles Firmin,[267] Theodore Beza,[268] William Whitaker,[269][270] Daniel Cawdry,[271] and Herbert Palmer,[272] Matthew Poole,[273] and Francis Turretin.[274][275] The commentary within the Geneva Bible implies that Paul's admonition is cultural rather than perpetual.[276]

Women cover their heads in some conservative Reformed and Presbyterian churches, such as the Heritage Reformed Congregations, Netherlands Reformed Congregations, Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland, Free Church of Scotland (Continuing), Free Presbyterian Church of North America and Presbyterian Reformed Church.[204][277][278][279]

Methodist

John Wesley, a principal father of Methodism, held that a woman, "especially in a religious assembly", should "keep on her veil".[280][281][282] The Methodist divines Thomas Coke, Adam Clarke, Joseph Sutcliffe, Joseph Benson and Walter Ashbel Sellew, reflected the same position – that veils are enjoined for women, while caps are forbidden to men while praying.[282][283]

Conservative Methodist women, like those belonging to the Fellowship of Independent Methodist Churches, wear head coverings.[284] The presence of headcovering in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and Christian Methodist Episcopal Church remains stable among women (additionally, those women commissioned as deaconesses wear a deaconness cap).[285][286][287]

Quaker

The Central Yearly Meeting of Friends, part of the Gurneyite-Orthodox branch of Quakerism, teaches that in 1 Corinthians 11 Paul instituted the veiling of women as "a Christian woman's way of properly honoring the headship of men in the church and of making a statement of submission to their authority (vs. 3, 5)."[288] The wearing of a veil is thus "the statement of genuine Christian piety and submission."[288] The same passage, in the view of the Central Yearly Meeting, teaches that in addition to a head covering, verses 14 and 15 teach that "nature has endowed women with a natural covering which is their long hair".[288] Given this, the Central Yearly Meeting holds that:[288]

While there are groups of Christians today who make their statement of submission by wearing coverings in keeping with this passage of Scripture, there are others who feel that in the present culture their long hair is sufficient to make such a statement. While we believe it is for those who wish to wear a covering to do so as a fine and becoming statement of submission, we urge them also to have their long and uncut. We believe regarding those Christian women who do not wear a covering that while it is proper for them to have their hair long, their long hair may not necessarily be a statement of piety since others in the world may have the same. For this reason, we believe that a Christian woman [who does not wear a head covering] makes her best statement of piety and submission by wearing her hair done up in a manner that is both feminine and unassuming.[288]

Conservative Friends (Quaker) women, including some from the Ohio Yearly Meeting (Conservative), wear head coverings usually in the form of a "scarf, bonnet, or cap."[31]

Plymouth Brethren

Plymouth Brethren women wear a headscarf during worship, in addition to wearing some form of headcovering in public.[289]

Baptist

Roger Williams, the founder of the first Baptist movement in North America, taught that women should veil themselves during worship as this was the practice of the early Church.[290]

Pentecostal

The wearing of a head covering during Pentecostal worship was the normative practice from its inception; in the 1960s, "head coverings stopped being obligatory" in many Pentecostal denominations of Western Europe, when, "with little debate", many Pentecostals "had absorbed elements of popular culture".[291]

Certain Pentecostal Churches, such as the Church of Our Lord Jesus Christ of the Apostolic Faith, Ukrainian Pentecostal Church, and the Christian Congregation continue to observe the veiling of women.[292][293][294]

Restorationist

Among certain congregations of the Church of Christ, it is customary for women to wear head coverings.[295]

The Davidian Seventh-day Adventist Church, in its official organ The Symbolic Code, teaches that women are to wear a head covering anytime when worshipping, both at church and at home, in view of 1 Corinthians 11.[296][297]

Female members of Jehovah's Witnesses may only lead prayer and teaching when no baptized male is available to, and must do so wearing a head covering.[298][299]

Shakers

In the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, Shaker girls and women wear a headcovering as a part of their daily wear.[300] These are in the form of a white cap.[300] Historically, these were sewn by Shaker women themselves, though in the middle of the 20th century, the rise of ready-made clothing allowed for the purchase of the same.[300]

Eastern Christianity

Among the churches of Eastern Christianity (including the Eastern Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Lutheran traditions), it has been traditionally customary for women to cover their heads with a headscarf while in church (and oftentimes in the public too); an example of this practice occurs among the Orthodox Christians in the region of Western Moldavia, among other areas.[42][43][208][301] In Albania, Christian women traditionally have worn white veils.[302][303]

Eastern Orthodox

An ancient Orthodox Christian prayer titled the "Prayer for binding up the head of a woman" has been used liturgically for the blessing of a woman's headcovering(s), which was historically worn by an Orthodox Christian woman at all times with the exception of sleeping:[5]

O God, you who have spoken through the prophets and proclaimed that in the final generations the light of your knowledge will be for all nations, you who desire that no human created by your hands remain devoid of salvation, you who through the apostle Paul, your elected instrument, ordered us to do everything for your glory, and through him you instituted laws for men and women who live in the faith, namely that men offer praise and glory to your holy name with an uncovered head, while women, fully armed in your faith, covering the head, adorn themselves in good works and bring hymns and prayers to your glory with modesty and sobriety; you, O master of all things, bless this your servant and adorn her head with an ornament that is acceptable and pleasing to you, with gracefulness, as well as honour and decorum, so that conducting herself according to your commandments and educating the members (of her body) toward self-control, she may attain your eternal benefits together with the one who binds her (head) up. In Jesus Christ our Lord, with whom to you belongs glory together with the most holy, good and life-giving Spirit, now and ever (and unto the ages of ages).[5]

Alexei Trader, the Eastern Orthodox bishop of the Diocese of Sitka and Alaska, delineated the teaching of the Church on a Christian woman's headcovering:[304]

In the Orthodox Church, the act of placing something under or behind a veil sets it apart as special, as something to be revered and respected, similar to the role played by the temple veil of the Holy of Holies in Jerusalem. Thus, there is a connection between a woman's veil with covering and revering that which is precious, such as the chalice that contains the wine that will become the Most-pure blood of Christ. And those coverings themselves also become holy. We can see this in the account of the Byzantine Empress Eudokia who donated her personal veil/head-covering to a monastery for use as an altar cloth. Of all articles of clothing, only a woman's head-covering could become a vestment for the holy altar, for it is already a kind of vestment.[304]

Bishop Alexei further stated that "Every Orthodox woman who wears a veil or head-covering is also blessed by that veil of the Mother of God, which miraculously and repeatedly protected the faithful from so much harm."[304]

Women belonging to the community of Old Believers wear opaque Christian head coverings, with those who are married keeping a knitted bonnet known as a povoinik underneath.[305]

However, in parishes of the Orthodox Church in America, the wearing of the headscarf is less common and is a matter of Christian liberty.[306]

Eastern Orthodox nuns wear a head covering called an apostolnik, which is worn at all times, and is the only part of the monastic habit which distinguishes them from Eastern Orthodox monks.

Oriental Orthodox

In Oriental Orthodox Christianity, Coptic women historically covered their head and face in public and in the presence of men.[307] During the 19th century, upper-class urban Christian and Muslim women in Egypt wore a garment which included a head cover and a burqa (muslin cloth that covered the lower nose and the mouth).[308] The name of this garment, harabah, derives from early Christian and Judaic religious vocabulary, which may indicate the origins of the garment itself.[308] Unmarried women generally wore white veils while married women wore black.[307] The practice began to decline by the early 20th century.[307]

The Standing Conference of Oriental Orthodox Churches (SCOOCH), which represents the Armenian, Coptic, Syrian, Indian, Ethiopian and Eritrean traditions of Oriental Orthodox Christianity, enjoins the wearing of a headcovering for a woman as being "Proper Attire in Church".[309]

Oriental Protestant

Women in the Believers Eastern Church, an Oriental Protestant denomination, wear head coverings.[310] Its former Metropolitan Bishop, K. P. Yohannan teaches that "When a woman wears the symbol of God's government, a head covering, she is essentially a rebuke to all the fallen angels. Her actions say to them, 'You have rebelled against the Holy God, but I submit to Him and His headship. I choose not to follow your example of rebellion and pride.'"[2]

Remove ads

Scriptural basis

Summarize

Perspective

Old Testament and Apocrypha/Deuterocanon

Passages such as Genesis 24:65,[311] Numbers 5:18,[312] Song of Solomon 5:7,[313] Susanna 1:31–32,[314] and Isaiah 47:2[315] indicate that women wore a head covering during the Old Testament era.[1][316] Song of Songs 4:1[317] records that hair is sensual in nature, with Solomon praising its beauty.[318] The removal of a woman's veil in the passage of Isaiah 47:1–3 is linked with nakedness and shame.[319]

New Testament

1 Corinthians 11:2–16[320] contains a key passage to the use of head coverings for women (and the uncovering of the heads of men).[22][321] Much of the interpretive discussion revolves around this passage.

Exegesis

Paul introduces this passage by praising the Corinthian Christians for remembering the "ordinances" (also translated as "traditions"[322] or "teachings")[323] that he had passed on to them (verse 2).[15] Included in these apostolic ordinances that Paul is discussing in 1 Corinthians 11 are the headcovering and the Eucharist.[324]

Paul then explains the Christian use of head coverings using the subjects of headship, glory, angels, natural hair lengths, and the practice of the churches.[1][325] This led to the universal practice of headcovering in Christianity.[34][1] Theologians David Lipscomb and J. W. Shepherd in their Commentary on 1st Corinthians explicate the theology behind the traditional Christian interpretation of 1 Corinthians 11, writing that Paul taught that "Every man, therefore, who in praying or prophesying covers his head, thereby acknowledges himself dependent on some earthly head other than his heavenly head, and thereby takes from the latter the honor which is due to him as the head of man." In the Old Testament, priests (who were all male) wore turbans and caps as Jesus was not known in that era, establishing "the reason why there was no command to honour Him by praying or prophesying with heads uncovered."[326] With the revelation of Jesus to humanity, "Any man who prays or prophesies with something on his head dishonours his head (Christ)."[326] In light of 1 Corinthians 11:4, Christian men throughout church history have thus removed their caps when praying and worshipping, as well as when entering a church.[327][328][329] As the biblical passage progresses, Paul teaches that:[326]

God's order for the woman is the opposite from His order for the man. When she prays or prophesies she must cover her head. If she does not, she disgraces her head (man). This means that she must show her subjection to God's arrangement of headship by covering her head while praying or prophesying. Her action in refusing to cover her head is a statement that she is equal in authority to man. In that case, she is the same as a woman who shaves her head like a man might do. Paul does not say that the woman disgraces her husband. The teaching applies to all women, whether married or not, for it is God's law that woman in general be subject to man in general. She shows this by covering her head when praying or prophesying.[326]

Ezra Palmer Gould, a professor at the Episcopal Divinity School, noted that "The long hair and the veil were both intended as a covering of the head, and as a sign of true womanliness, and of the right relation of woman to man; and hence the absence of one had the same significance as that of the other."[330] This is reflected in the patristic teaching of the Early Church Father John Chrysostom, who explained the two coverings discussed by Saint Paul in 1 Corinthians 11:[331]

For he said not merely covered, but covered over, meaning that she be with all care sheltered from view on every side. And by reducing it to an absurdity, he appeals to their shame, saying by way of severe reprimand, but if she be not covered, let her also be shorn. As if he had said, "If thou cast away the covering appointed by the law of God, cast away likewise that appointed by nature."[331]

John William McGarvey, in delineating verse 10 of 1 Corinthians 11, suggested that "To abandon this justifiable and well established symbol of subordination would be a shock to the submissive and obedient spirit of the ministering angels (Isaiah 6:2) who, though unseen, are always present with you in your places of worship (Matthew 18:10–31; Psalm 138:1; 1 Timothy 5:21; ch. 4:9; Ecclesiastes 5:6)".[332] Furthermore, verse 10 refers to the cloth veil as a sign of power or authority that highlights the unique God-given role of a Christian woman and grants her the ability to then "pray and prophesy with the spiritual gifts she has been given" (cf. complementarianism).[295] This was taught by Early Church Father Irenaeus (120–202 AD), the last living connection to the Apostles, who in his explication of Saint Paul's command in 1 Corinthians 11:10, delineated in Against Heresies that the "authority" or "power" on a woman's head was a cloth veil (κάλυμμα kalumma).[333] Irenaeus' explanation constitutes an early Christian commentary on this biblical verse.[334] Related to this is the fact that Verse 10, in many early copies of the Bible (such as certain vg, copbo, and arm), is rendered with the word "veil" (κάλυμμα kalumma) rather than the word "authority" (ἐξουσία exousia); the Revised Standard Version reflects this, displaying the verse as follows: "That is why a woman ought to have a veil on her head, because of the angels".[335][334] Similarly, a scholarly footnote in the New American Bible notes that presence of the word "authority (exousia) may possibly be due to mistranslation of an Aramaic word for veil".[336] This mistranslation may be due to "the fact that in Aramaic the roots of the word power and veil are spelled the same."[337] Ronald Knox adds that certain biblical scholars hold that "Paul is attempting, by means of this Greek word, to render a Hebrew word that signifies the veil traditionally worn by a married Jewish woman."[338] Nevertheless, the "word exousia had come at Corinth, or in the Corinthian Church, to be used for 'a veil,' or 'covering'...just as the word 'kingdom' in Greek may be used for 'a crown' (compare regno as the name of the pope's tiara), so authority may mean a sign of authority (Revised Version), or 'a covering, in sign that she is under the power of her husband' (Authorized Version, margin)."[339][340] Jean Chardin's scholarship on the Near East thus notes that women "wear a veil, in sign that they are under subjection."[339][340] In addition to Irenaeus, Church Fathers, including Hippolytus, Origen, Chrysostom, Epiphanius, Jerome, Augustine, and Bede write verse 10 using the word "veil" (κάλυμμα kalumma).[334][341]

Certain denominations of Christianity, such as traditional Anabaptists (e.g. Conservative Mennonites), combine this with 1 Thessalonians 5 ("Rejoice always; pray without ceasing; in everything give thanks; for this is God's will for you in Christ Jesus. Do not quench the Spirit; do not despise prophetic utterances")[342] and hold that Christian women are commanded to wear a headcovering without ceasing.[343][24] Anabaptist expositors, such as Daniel Willis, have cited the Early Church Father John Chrysostom, who provided additional reasons from Scripture for the practice of a Christian woman wearing her headcovering all the time – that "if to be shaven is always dishonourable, it is plain too that being uncovered is always a reproach" and that "because of the angels...signifies that not at the time of prayer only but also continually, she ought to be covered."[344][28][32] A Conservative Anabaptist publication titled The Significance of the Christian Woman's Veiling, authored by Merle Ruth, teaches with regard to the continual wearing of the headcovering by believing women, that it is:[29]

... worn to show that the wearer is in God's order. A sister should wear the veiling primarily because she is a woman, not because she periodically prays of teaches. It is true that verses 4 and 5 speak of the practice in relation to times of praying and prophesying. But very likely it was for such occasions that the Corinthians had begun to feel they might omit the practice in the name of Christian liberty. The correction would naturally be applied first to the point of violation. Greek scholars have pointed out that the clause "Let her be covered" is the present, active, imperative form, which gives the meaning, "Let her continue to be veiled."[29]

The biblical passage has been interpreted by Anabaptist Christians and Orthodox Christians, among others, in conjunction with modesty in clothing (1 Timothy 2:9–10 "I also want the women to dress modestly, with decency and propriety, adorning themselves, not with elaborate hairstyles or gold or pearls or expensive clothes, but with good deeds, appropriate for women who profess to worship God").[345] Genesis 24:65[8] records the veil as a feminine emblem of modesty.[9][10][1] The wearing of head coverings in public by Christian women was commanded in early Christian texts, such as the Didascalia Apostolorum and the Pædagogus, for the purpose of modesty.[11][346]

Verse four of 1 Corinthians 11 uses the Greek words kata kephalēs (κατάIn κεφαλῆς) for "head covered", the same Greek words used in Esther 6:12[347] (Septuagint) where "because he [Haman] had been humiliated, he headed home, draping an external covering over his head" (additionally certain manuscripts of the Septuagint in Esther 6:12 use the Greek words κατακεκαλυμμένος κεφαλήν, which is the "perfect passive participle of the key verb used in 1 Corinthians 11:6 and 7 for both a man's and a woman's covering his or her head [κατακαλύπτω]") – facts that New Testament scholar Rajesh Gandhi states makes it clear that the passage enjoins the wearing of a cloth veil by Christian women.[348][349] Biblical scholar Christopher R. Hutson contextualizes the verse citing Greek texts of the same era, such as Moralia:[350]

Plutarch's phrase, "covering his head" is literally "having down from the head" (kata tes kephales echon). This is the same phrase Paul uses in 1 Corinthians 11:4. It refers to the Roman practice of pulling one's toga up over the head like a hood. ... Romans also wore their togas "down from the head" when they offered sacrifices. This is the practice to which Paul refers.[350]

Verses five through seven, as well as verse thirteen, of 1 Corinthians 11 use a form of the Greek word for "veiled", κατακαλύπτω katakalupto; this is contrasted with the Greek word περιβόλαιον peribolaion, which is mentioned in verse 15 of the same chapter, in reference to "something cast around" as with the "hair of a woman ... like a mantle cast around".[17][351][352][353] These separate Greek words indicate that there are thus two head coverings that Paul states are compulsory for Christian women to wear, a cloth veil and her natural hair.[35][349] The words Paul uses in 1 Corinthians 11:5 are employed by contemporary Hellenistic philosophers, such as Philo (30 BC–45 AD) in Special Laws 3:60, who uses "head uncovered" (akatakalyptō tē kephalē) [ἀκατακαλύπτῳ τῇ κεφαλῇ] and "it is clear that Philo is speaking of a head covering being removed because the priest had just removed her kerchief"; additionally, akatakalyptos [ἀκατακάλυπτος] likewise "means 'uncovered' in Philo, Allegorical Interpretation II,29, and in Polybius 15,27.2 (second century BC)."[354] 1 Corinthians 11:16[355] concludes the passage Paul wrote about Christian veiling: "But if anyone wants to argue about this, I simply say that we have no other custom than this, and neither do God's other churches."[15] Michael Marlowe, a scholar of biblical languages, explains that Saint Paul's inclusion of this statement was to affirm that the "headcovering practice is a matter of apostolic authority and tradition, and not open to debate", evidenced by repeating a similar sentence with which he starts the passage: "maintain the traditions even as I delivered them to you".[15]

Interpretive issues

There are several key sections of 1 Corinthians 11:2–16 that Bible commentators and Christian congregations, since the 1960s, have held differing opinions about, which have resulted in either churches continuing the practice of wearing head coverings, or not practicing the ordinance.[211][356]

- Gender-based headship: Paul connects the use (or non-use) of head coverings with the biblical distinctions between each gender. In 1 Corinthians 11:3,[357] Paul wrote, "Christ is the head of every man, and the man is the head of a woman." He immediately continues with a gender-based teaching on the use of head coverings: "Every man who has something on his head while praying or prophesying disgraces his head. But every woman who has her head uncovered while praying or prophesying disgraces her head."[15]

- Glory and worship: Paul next explains that the use (or non-use) of head coverings is related to God's glory during times of prayer and prophesy. In 1 Corinthians 11:7,[358] he states that man is the "glory of God" and that for this reason "a man ought not to have his head covered." In the same verse, Paul also states that the woman is the "glory of man." He explains that statement in the subsequent two verses by referring to the woman's creation in Genesis 2:18,[359] and then concludes, "Therefore the woman ought to have a symbol of authority on her head" (verse 10). In other words, the "glory of God" (man) is to be uncovered during times of worship, while the "glory of man" (woman) is to be covered.[15]

- Angels: In 1 Corinthians 11:10,[360] Paul says "Therefore the woman ought to have a symbol of authority on her head, because of the angels" (NASB), also rendered "That is why a woman ought to have a veil on her head, because of the angels" (RSV). Many interpreters admit that Paul does not provide much explanation for the role of angels in this context. Some popular interpretations of this passage are:

- An appeal not to offend the angels by disobedience to Paul's instructions of women wearing a veil (and men praying with their heads uncovered) as the angels take part in spiritual exercises (Tobit 12:12–15, Revelation 8:2–4)[361][362][363][332][1]

- a command to accurately show angels a picture of the created order (Ephesians 3:10,[364] 1 Peter 1:12),[365]

- a warning for mankind to obey as a means of accountability, since the angels are watching (1 Timothy 5:21),[366]

- to be like the angels who cover themselves in the presence of God (Isaiah 6:2),[367][29] and

- to protect against the fallen angels who lust after mortal women and did not stay in the role that God created for them (Jude 1:6).[368][369]

According to Dale Martin, Paul is concerned that angels may look lustfully at beautiful women, as the "sons of God" in Genesis 6 apparently did. Noting the similarity between the Greek word translated "veil" and the Greek word for a seal or cork of a wine jug, Martin theorizes that the veil acted not only to conceal the beauty of a woman's hair, but also as a symbolic protective barrier that "sealed" the woman against the influence of fallen angels.[370] Other scholars, such as Joseph Fitzmyer, believe the angels spoken of here are not fallen angels looking lustfully at women, but good angels who watch over church services. Notably, the author of Hebrews mentions "entertaining angels" and evidence from the Dead Sea Scrolls suggests some Second Temple era Jews believed angels attended synagogue services. According to this view, Paul's concern is not that an angel looks lustfully, but simply that the appearance of an inappropriately dressed women might offend the heavenly guardians.[371] A third interpretation comes from Bruce Winter, who theorizes that the "angels" spoken of are not heavenly beings at all, but simply human visitors. Winter notes that the Greek word translated "angels" literally means "messengers" and could refer to a visitor carrying a letter from afar, possibly even the epistle itself. In this view, Paul is concerned that if a visitor to a church service sees a married woman with her head uncovered, he may judge that woman to be promiscuous. Thus, Paul seeks to protect the church community's honour by ensuring that all members appear above reproach.[372]

- Nature and hair lengths: In 1 Corinthians 11:13–15,[373] Paul asks a rhetorical question about the propriety of head coverings, and then answers it himself with a lesson from nature: "Judge for yourselves: is it proper for a woman to pray to God with her head uncovered? Does not even nature itself teach you that if a man has long hair, it is a dishonor to him, but if a woman has long hair, it is a glory to her? For her hair is given to her for a covering." The historic interpretation of this passage, for example seen in Homilies of John Chrysostom, an Early Church Father, reiterates Paul's teaching that since a woman naturally "covers" her head with her natural hair, she likewise ought to cover it with a cloth headcovering while praying or prophesying (cf. conditional sentence).[35][331]

Thus, in the beginning he simply requires that the head be not bare: but as he proceeds he intimates both the continuance of the rule, saying, "for it is one and the same thing as if she were shaven," and the keeping of it with all care and diligence. For he said not merely covered, but "covered over," meaning that she be carefully wrapped up on every side. And by reducing it to an absurdity, he appeals to their shame, saying by way of severe reprimand, "but if she be not covered, let her also be shorn." As if he had said, "If thou cast away the covering appointed by the law of God, cast away likewise that appointed by nature." — John Chrysostom[374]

Michael Marlowe, a scholar of biblical languages, explicates the reductio ad absurdum that Paul the Apostle used in the passage:[15]

In the appeal to "nature" (φύσις) here Paul makes contact with another philosophy of ancient times, known as Stoicism. The Stoics believed that intelligent men could discern what is best in life by examining the laws of nature, without relying on the changeable customs and divers laws made by human rulers. If we consult Nature, we find that it constantly puts visible differences between the male and the female of every species, and it also gives us certain natural inclinations when judging what is proper to each sex. So Paul uses an analogy, comparing the woman's headcovering to her long hair, which is thought to be more natural for a woman. Though long hair on men is possible, and in some cultures it has been customary for men to have long hair, it is justly regarded as effeminate. It requires much grooming, it interferes with vigorous physical work, and a man with long hair is likely to be seized by it in a fight. It is therefore unmanly by nature. But a woman's long hair is her glory. Here again is the word δόξα, used opposite ἀτιμία "disgrace," in the sense of "something bringing dishonor." Long and well-kept hair brings praise to a woman because it contributes to her feminine beauty. The headcovering, which covers the head like a woman's hair, may be seen in the same way. Our natural sense of propriety regarding the hair may therefore be carried over to the headcovering.[15]

Paul's discussion of hair lengths was not to command any specific hair measurement, but rather, a discussion of "male and female differentiation" as women generally had longer hair than men; while the males of Sparta wore shoulder-length hair, the hair of Spartan women was significantly longer.[375]

- Church practice: In 1 Corinthians 11:16,[376] Paul responded to any readers who may disagree with his teaching about the use of head coverings: "But if one is inclined to be contentious, we have no other practice, nor have the churches of God." This may indicate that head coverings were considered a standard, universal Christian symbolic practice (rather than a local cultural custom). In other words, while churches were spread out geographically and contained a diversity of cultures, they all practiced headcovering for female members.[15]

Contemporary conclusions

Beginning in the 20th century, due to aforementioned issues, Bible commentators and Christian congregations have either advocated for the continued practice of wearing head coverings, or have discarded the observance of this ordinance as understood in its historic sense.[2][356] While many Christian congregations, such as those of the Conservative Anabaptists, continue to enjoin the wearing of head coverings for female members, others do not.[46][377][356]

- Some Christian denominations, such as Anabaptist Churches and Orthodox Churches, view Christian headcovering as a practice that Paul intended for all Christians, in all locations, during all time periods and so they continue the practice within their congregations. This view was taught by the early Church Fathers and held universally by undivided Christianity for several centuries afterward.[34][2] This historic interpretation is linked with the God-ordained order of headship.[378] Conservative Anabaptists and Old Order Anabaptists hold that because "the testimony of headship and the angels apply to all times of the believer's life, not only church services", in addition to biblical injunctions to "pray often, even continually (Acts 6:3–4, 6; 12:5; Romans 1:8–10; Ephesians 1:15–19; 6:18–20; Colossians 1:3–4; 5:17; 2 Timothy 1:3–6)", women are called to wear the headcovering throughout the day.[379] Sociologist Cory Anderson stated that for those Christian women who continually wear it, the headcovering serves as an outward testimony that often allows for evangelism.[379]

- A modern interpretation is that Paul's commands regarding headcovering were a cultural mandate that was only for the 1st-century Corinthian church. This view states that Paul was simply trying to create a distinction between uncovered Corinthian prostitutes and godly Corinthian Christian women, and that in the modern era, head coverings are not necessary within a church.[46] Church historian David Bercot criticizes this view as early Church writings do not evidence this reasoning.[46]

- A recent interpretation, first formulated in 1965 by the Scandinavian theologian Abel Isaakson, purports that Paul stated that the "hair" (specifically "long hair") is the sole covering mentioned in the entire passage; 1 Corinthians 11:15 (NRSV) reads "but if a woman has long hair, it is her glory? For her hair is given to her for a covering."[380][381][34][282] However, some have taken issue with the fact that the Greek word used for covering in verse 15 (περιβόλαιον) is a different word than the form of the word used for veiling/covering in verses 5–7 and 13 (κατακαλύπτω), the latter of which means "to cover wholly" or "to veil".[35][351][349][352][382] Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland (Continuing) John W. Keddie contended that if hair was the covering Paul was talking about, then verse 6 would read "For if the women have no hair on her head, let her also be shorn", rendering the passage to be nonsensical.[35][381]

Remove ads

Legal issues

Summarize

Perspective

In the United States, an Alabama resident Yvonne Allen, in 2016, filed a complaint with the federal court after being forced to remove her headscarf for her driver's license photograph.[383][384] Allen characterized herself as a "devout Christian woman whose faith compels her to cover her hair in public."[383][385] In Allen v. English, et al., Lee County was accused of violating the Establishment Clause and a settlement was negotiated that gave "Allen a new driver’s license with her head covering".[386]

In 2017, after a prison warden associated with the United States Penitentiary of Atlanta forced Christian prison visitor Audra Ragland to remove her headscarf, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) sent a letter to the Federal Bureau of Prisons that asked for an action plan to ensure that the same would not occur again and that otherwise, the Federal Bureau of Prisons would be exposed to legal liability.[387] Audra Ragland cited 1 Corinthians 11 as the reason behind the practice of Christian covering and noted that she felt "exposed and embarrassed as she had to walk in front of so many men whom she did not know" and that she was "sickened that she had to potentially compromise her faith" in order to visit her brother.[387] The ACLU noted that the prison warden's coercion constituted "religious discrimination in violation of the First Amendment, the U.S. Bureau of Prisons' policy governing visitors' religious head wear and the U.S. Penitentiary of Atlanta's policies."[387]

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads