China Cables

Leak of Chinese government documents detailing re-education camps in Xinjiang From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The China Cables are a collection of secret Chinese government documents from 2017 which were leaked by exiled Uyghurs to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, and published on 24 November 2019. The documents include a telegram which details the first known operations manual for running the Xinjiang internment camps, and bulletins which illustrate how China's centralized data collection system and mass surveillance tool, known as the Integrated Joint Operations Platform, uses artificial intelligence to identify people for interrogation and potential detention.[1]

The Chinese government has called the cables "pure fabrication" and "fake news", further stating that the West were "slandering and smearing" them. The documents release sparked renewed attention to the Uyghur internment camps and persecution of Uyghurs in China.[2]

Description and contents

Summarize

Perspective

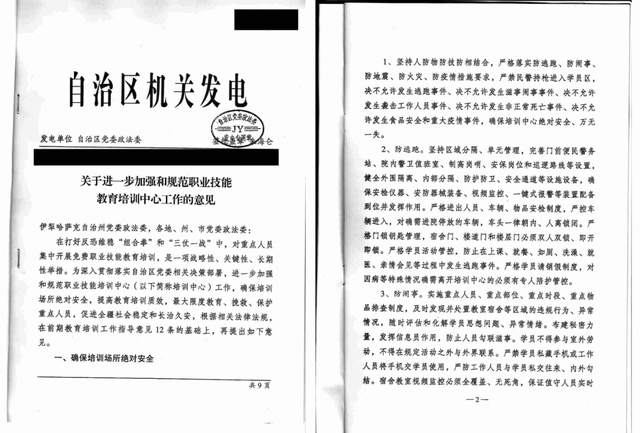

On November 24, 2019, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists published secret Chinese government documents from 2017 dubbed as the "China Cables", which exiled Uyghurs had leaked to them. The documents consisted of a classified telegram called "New Secret 5656"[a] from 2017, four bulletins/security briefings and one court document.[3]

The classified telegram detailed the first known operations manual for running "between 1,300 and 1,400" internment camps of Muslim Uyghurs in Xinjiang,[4] It was signed by Zhu Hailun, head of Xinjiang's Political and Legal Commission A, then deputy secretary of Xinjiang's Party Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. According to the American delegate to the UN committee on the elimination of racial discrimination, China is holding one million Uyghurs in these camps.[5][3]

The 4 bulletins are secret government intelligence briefings from China's centralized data collection system "Integrated Joint Operation Platform" (IJOP), which uses artificial intelligence to identify people for questioning and potential detention. It illustrated a connection between mass surveillance in China and the Xinjiang camps, confirming earlier suspicions from multiple international news sources.[6][7][8] For example, the predictive policing program flagged 1.8 million Uyghur users for investigation who had installed the file sharing app Zapya developed by the Chinese company Dewmobile on their phones.[9] One of the bulletins reveals that during one week in June 2017 the IJOP system detected 24,412 "suspicious" persons in southern Xinjiang, 15,683 of whom were sent to "education and training" and 706 were "criminally detained".[9]

The non-classified court document is the sentencing of a Uyghur man to 10 years in jail for telling his colleagues not to watch pornography or consume alcohol, and to pray regularly. He also stated that "All people who do not pray are Han Chinese kafirs."[3]

The main contents are:[10]

- The camps are secret and how secrecy about their existence can be maintained.

- Escapes are prevented by "guard towers, double-locked doors, alarms, blanket video surveillance and front gate security".

- The camps are forced ideological and behavioral reeducation centers.

- Detainees are held for a minimum of a year but can be imprisoned for an indefinite period.

- Methods of forced indoctrination are detailed. For example, "detainees are scored on their use of Mandarin and their adherence to the camp's strict rules that govern everything from where they eat, carry out chores, study or even go to the toilet."

- Prisoners receive vocational training only after release in separate facilities.

- Methods of how to control infectious disease outbreaks are detailed.

Publication and press reports

Summarize

Perspective

The cables publication by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and collaborating media in 14 countries on November 23, 2019, followed a New York Times report on November 16[11][2] "puts to rest attempts by the Chinese government to portray the facilities in the western province of Xinjiang as anything other than internment camps" according to The Irish Times.[12] In 2018, the Chinese government had "legalized" the internment camps for people accused of religious extremism, after denying such centers even existed.[13]

El País wrote that the Chinese Embassy in Madrid did not answer their four questions, namely: If it collects and sends information about Uyghur citizens living in Spain or Europe to Beijing? How their visa policy has changed since 2017? If Beijing had requested to extradite Uyghur people? And if Uyghurs have the same rights as other Chinese nationals before the Embassy?[14] On December 3, 2019 Deutschlandfunk reported that China has been using DNA samples collected in the prison camps together with facial recognition technology to "map faces", a project which had been supported by European scientists. There were concerns that the system is used to facilitate ethnic profiling.[15] The German Max Planck Society founded the "Partner Institute for Computational Biology" and funded one scientist from the Beijing Institute of Genomics with a grant, even though he was employed by the Chinese police, the Ministry of Public Security. He published findings exploring the DNA of physical appearance traits in 2018 and 2019 in the journal Human Genetics by Springer Nature, and said he had been unaware of the origins of the DNA samples of the men from Tumxuk.[16] The NYT had first reported about ethnic phenotyping in spring of 2019, calling it "automated racism".[17]

Political reactions

Summarize

Perspective

Domestic

On November 24, 2019, Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang said that the affairs in Xinjiang were an "internal matter". The Chinese embassy in London called the cables "pure fabrication" and "fake news".[2] China has censored reports about the cables and erased almost all references to ICIJ searches on the Chinese internet,[18] according to Süddeutsche Zeitung, one of the collaborators of ICIJ China Cables.

International

European Union

In December 2019, the European Parliament approved a resolution condemning the treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. The resolution on China was adopted by 505 votes in favour, 18 against, with 47 abstentions. The resolution called on the Chinese Government to put an end to arbitrary detentions, without any charge, trial or conviction for criminal offence, of the Uyghur, Kazakh, or Tibetan ethnic minorities. The Parliament called for the sanctioning of companies and individuals that are complicit with any acts that would deter human rights.[19][20][21][22]

Germany

In November 2019, Germany's foreign minister Heiko Maas condemned the internment of Uyghurs and insisted on talks with the Chinese government to gain access to the camps.[18]

One year after the publication of the Cables, as of November 2020, no mission of independent observers has assessed the human rights situation on the ground, as the German government had originally announced. The Auswärtiges Amt said it was watching the situation and that ambassadors of EU countries were trying to travel to Xinjiang. A speaker of the Mercator Institute for China Studies said that the COVID-19 pandemic had allowed China to quarantine the region even more.[23]

United Kingdom

On 25 November 2019, the UK Foreign Office called for "immediate and unfettered UN access to the detention camps", per The Guardian, another one of the ICIJ China Cables collaborators.[24]

United States

On November 26, 2019, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said documents confirmed China intentionally committing very significant human rights abuses in Xinjiang.[25] On October 8, 2019, amidst trade talks between the US and China, Pompeo had introduced visa restrictions on Chinese government and Communist Party officials "who are believed to be responsible for, or complicit in, the detention or abuse of Uyghurs, Kazakhs or other members of Muslim minority groups in Xinjiang, China."[26]

On 3 December 2019, the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act was passed by the United States House of Representatives, awaiting consent by the Senate. It condemns abuses against Muslims, calls for the closure of mass detention camps and calls for sanctions against Chen Quanguo.[27] On June 17, 2020, US President Donald Trump signed the bill into law a week after it was passed by a veto-proof majority in Congress.[28][29]

Others

As of November 2019, there had been no response by any United Nations personnel, nor any response from Australia, Japan, Canada, any Middle Eastern state, nor by the International Olympic Committee considering the fact that Beijing was to be hosting the 2022 Winter Olympics.[30]

Effects on foreign businesses in Xinjiang

As of May 2019, there were at least 68 companies originating from the European Union, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom that have ties to Xinjiang.[31] About a dozen were German companies; Volkswagen Group operates a relatively unprofitable car manufacturing plant in Urumqi since 2013, employing 650 workers, which was criticised as existing for solely political reasons.[32]

Bosch warned the Chinese authorities against internment of their employees and said that the company offers Muslim prayer rooms for staff.[33]

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.