Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Chilam Balam

Yucatec Mayan literature From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

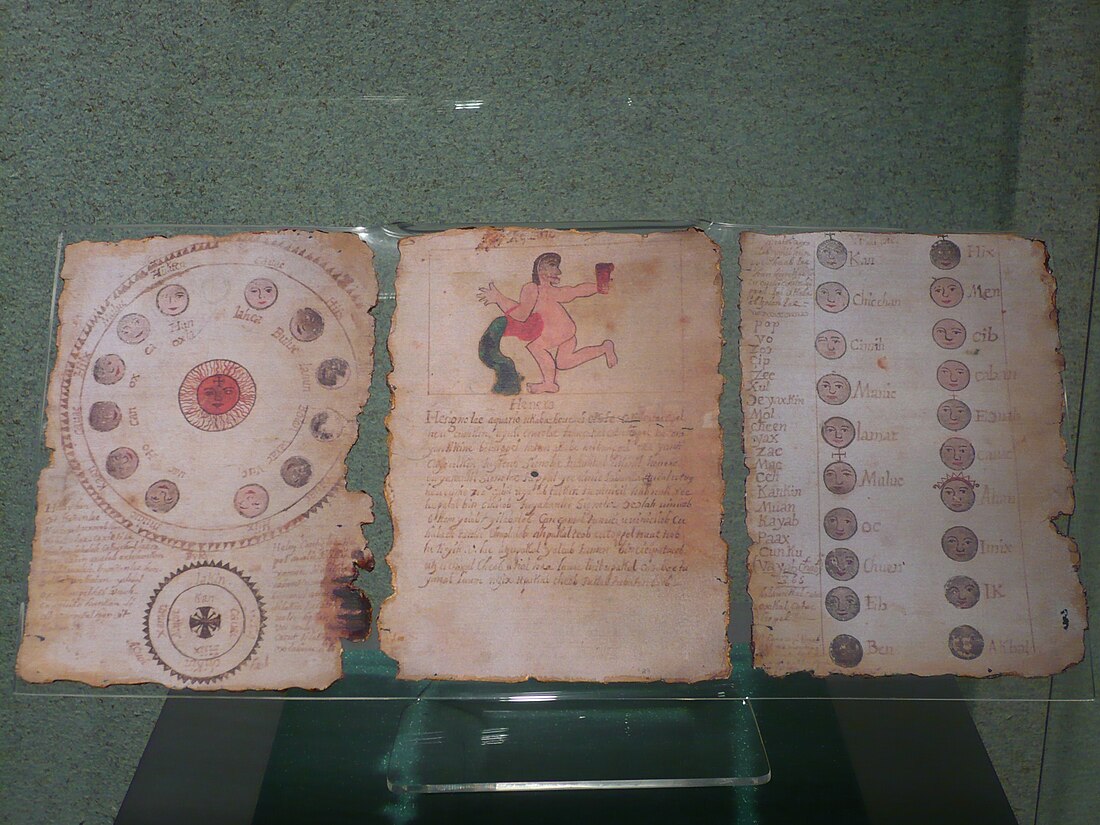

The Books of Chilam Balam (Mayan pronunciation: [t͡ʃilam ɓahlam]) are handwritten, chiefly 17th and 18th-centuries Maya miscellanies, named after the small Yucatec towns where they were originally kept, and preserving important traditional knowledge in which indigenous Maya and early Spanish traditions have coalesced. They compile knowledge on history, prophecy, religion, ritual, literature, the calendar, astronomy, and medicine.[1] Written in the Yucatec Maya language and using the Latin alphabet, the manuscripts are attributed to a legendary author called Chilam Balam, a chilam being a priest who gives prophecies and balam a common surname meaning ʼjaguarʼ. Chilam Balam was notable for correctly predicting the coming of the Spaniards to Yucatán.[2]

Nine Books of Chilam Balam are known,[3] most importantly those from Chumayel, Maní, and Tizimín,[4] but more have existed. Both language and content show that parts of the books date back to the time of the Spanish conquest of the Yucatec kingdoms (1527–1546). In some cases, where the language is particularly terse, the books appear to render hieroglyphic script, and thus to hark back to the pre-conquest period.

Remove ads

Contents

Summarize

Perspective

Taken together, the Books of Chilam Balam provide an account of the fullness of 18th-century Yucatec-Maya spiritual life. Whereas the medical texts and chronicles are quite matter-of-fact, the riddles and prognostications make abundant use of traditional Mayan metaphors. This holds even more true of the mythological and ritualistic texts, which, cast in abstruse language, plainly belong to esoteric lore. The historical texts derive part of their importance from the fact that they have been cast in the framework of the native Maya calendar, partly adapted to the European calendrical system. Reconstructing Postclassic Yucatec history from these data has proven to be an arduous task. The following is an overview of the sorts of texts—partly of Mesoamerican, and partly of Spanish derivation—found in the Chilam Balam books.

1. History

- Histories, cast in the mold of the indigenous calendar: migration legends; narratives concerning certain lords of the indigenous kingdoms; and chronicles up to and including the Spanish conquest.

- Prognostication, cast in the framework of the succession of haabs (years), tuns (360-day periods) and kʼatuns (20X360-day periods).

- Prophecy, ascribed to famous early 16th-century oracular priests.

2. Formularies with metaphors

- Collections of riddles, used for the confirmation of local lords into their offices (the so-called 'language of Zuyua').

3. Myth and mysticism

- Myth, particularly the destruction and re-creation of the world as connected to the start of kʼatun 11 Ahau.[5]

- Ritualistic mysticism, particularly concerning the creation of the twenty named days (uinal); the ritual of the 'Four Burners' (ahtoc); and the birth of the maize, or 'divine grace' (the so-called 'Ritual of the Angels').[6]

4. Practical calendars and classifications

- Classifications according to the twenty named days (correlating birds of tiding, plants and trees, human characters, and professional activities).

- Treatises on astrology, meteorology, and the Catholic liturgical calendar (the so-called reportorios de los tiempos). The astrology is Ptolemaic and includes the European zodiac.

- Agricultural almanacs.

5. Medical recipes

- Herbal medicine: The Chilam Balam books contain the sort of medical prescriptions that derive from Greek and Arab traditions, rather than the Mayan 'incantation approach', as represented by the Ritual of the Bacabs.[7]

6. Spanish traditions

- Roman Catholic instruction: feast days of the saints, tracts, and prayers.

- Spanish romance, such as the tale of the 'Maiden Theodora'.

Remove ads

Scholarship

Summarize

Perspective

Since many texts recur in various books of Chilam Balam, establishing a concordance and studying substitution patterns is fundamental to scholarship.[8] The archaic Yucatec idiom and the allusive, metaphorical nature of many texts present a formidable challenge to translators. The outcome of the translation process is sometimes heavily influenced by external assumptions about the texts' purpose. As a result of these factors, the quality of existing translations varies greatly.

The Spanish-language synoptic translation of Barrera Vásquez and Rendón (1948) is still useful. To date (2012), complete English translations are available for the following Books of Chilam Balam:

- Chumayel (authoritative edition: Roys 1933 [1967]; compare with Edmonson 1986)

- Maní (embedded in the Pérez Codex: Craine and Reindorp 1979, an adaptation of the 1949 Mexican translation of Solís Alcalá)

- Tizimín (Edmonson 1982)

- Na (Gubler and Bolles 2000)

- Kaua (Bricker and Miram 2002)

An excellent overview and discussion of the syncretism involved is to be found in the introduction to the Bricker and Miram edition of the Book of Chilam Balam of Kaua.[9] A detailed analysis and interpretation of the main mythological and ritualistic texts with a view to their syncretic origins is given by Knowlton (2010).

Remove ads

In popular culture

The Books of Chilam Balam are referenced in The Falling Woman by Pat Murphy as source material for the description of sacrifices at Chichén Itzá.

A poem from the Chilam Balam is prominently featured in a short story by the U.S.-born writer Lucia Berlin, who spent many years living and traveling in Latin America, including Chile and Mexico. The poem gives Berlin's story its title. Here is the poem: "Toda Luna, todo año,/ Todo día, todo viento/ Camina y pasa también./ También toda sangre llega/ Al lugar de su quietud." The Spanish is a translation from the Mayan by Antonio Mediz Bolio. The story's heroine translates the poem as follows: "Every moon, every year/ Every day, every breeze/ Goes along, and passes away./ And thus all blood arrives/ To its own quiet place."[10]

A brief excerpt from Chilam Balam is used as a prelude to Chapter 3 of the Cuban novel "The Lost Steps" by Alejo Carpentier (1953).

See also

Notes

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads