Celtic language decline in England

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Prior to the 5th century AD, most people in Great Britain spoke a Brythonic language, but the number of these speakers declined sharply throughout the Anglo-Saxon period (between the 5th and 11th centuries), when Brythonic languages were displaced by the West Germanic dialects that are now known collectively as Old English.

Debate continues over whether this change was due to mass migration or to a small-scale military takeover, not least because the situation was strikingly different from, for example, post-Roman Gaul, Iberia or North Africa, where invaders speaking other languages gradually switched to local languages.[1][2][3] This linguistic decline is therefore crucial to understanding the cultural changes in post-Roman Britain, the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain and the rise of an English language.

The notable exceptions were the Cornish language persisting into the 18th century, and a form of Welsh remaining in common usage in the English counties along the Welsh border into the late 19th century.[4][5]

Chronology

Summarize

Perspective

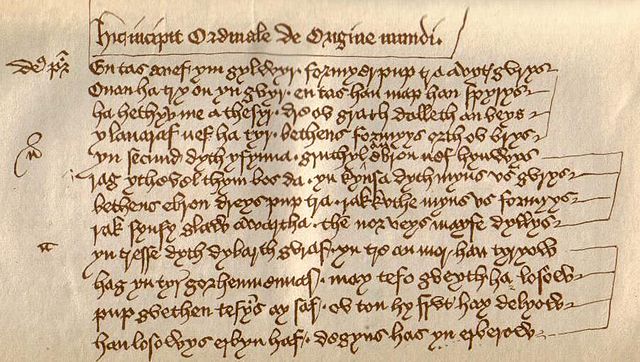

Fairly extensive information about language in Roman Britain is available from Roman administrative documents attesting to personal and place-names, along with archaeological finds such as coins, the Bloomberg and Vindolanda tablets, and Bath curse tablets. That shows that most inhabitants spoke British Celtic and/or British Latin. The influence and position of British Latin declined when the Roman economy and administrative structures collapsed in the early 5th century.[7][8][9]

There is little direct evidence for the linguistic situation in Britain for the next few centuries. However, by the 8th century, when extensive evidence for the language situation in England is next available, it is clear that the dominant language was what is today known as Old English. There is no serious doubt that Old English was brought to Britain primarily during the 5th and 6th centuries by settlers from what are now the Netherlands, north-western Germany, and southern Denmark who spoke various dialects of Germanic languages[10][11] and who came to be known as Anglo-Saxons. The language that emerged from the dialects they brought to Britain is today known as Old English. There is evidence for Britons moving westward, and also across the English Channel to Brittany, but those who remained in what became England switched to speaking Old English until Celtic languages were no longer extensively spoken there. Celtic languages continued to be spoken in other parts of the British Isles, such as Wales, Scotland, Ireland and Cornwall. Only a few English words of Brittonic origin appear to have entered Old English.[12][13]

Because the main evidence for events in Britain during the crucial period (400–700) is archaeological and seldom reveals linguistic information, and written evidence even after 700 remains patchy, the precise chronology of the spread of Old English is uncertain. However, Kenneth Jackson combined historical information from texts like Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731) with evidence for the linguistic origins of British river names to suggest the following chronology, which remains broadly accepted (see map):

- In Area 1, Celtic names are rare and confined to large and medium-sized rivers. This area corresponds to English language dominance up to c. 500–550.

- Area 2 shows English-language dominance c. 600.

- Area 3, where even many small streams have Brittonic names, shows English-language dominance c. 700.

- In Area 4, Brittonic remained the dominant language until at least the Norman Conquest, and river names are overwhelmingly Celtic.[14]

Although Cumbric, in the northern part of Area 3, seems to have died during the 11th century,[15] Cornish continued to thrive until the early modern period and retreated at only around 10 km per century. However, from about 1500, Cornish–English bilingualism became increasingly common, and Cornish retreated at closer to 30 km per century. Cornish fell out of use entirely during the 18th century, though the last few decades have seen an attempted revival.[16] Welsh continued to be spoken in some western parts of Herefordshire and Shropshire into modern times.

During that period, England was also home to influential communities speaking Latin, Old Irish, Old Norse and Anglo-Norman. None of those seem to have been a major long-term competitor to English and Brittonic, however.

Debate on whether British Celtic was being displaced by Latin before the arrival of English

Summarize

Perspective

As of around 2010 there was an ongoing discussion about the character of British Celtic and the extent of Latin-speaking in Roman Britain.[17][9][18] Scholars agreed that British Latin was spoken as a native language in Roman Britain and that at least some of the dramatic changes that the Brittonic languages underwent around the 6th century were due to Latin speakers switching language to Celtic,[19] possibly as Latin speakers moved away from encroaching Germanic-speaking settlers.[20] It was thought likely that Latin was the language of most of the townspeople; the administration and the ruling class; the military and the church. Some scholars thought that British Celtic probably remained the language of the peasantry, which was the bulk of the population; the rural elite was probably bilingual.[21] But others suggested that Latin became the prevalent language of lowland Britain, in which case the story of Celtic language death in what is now England begins with its extensive displacement by Latin.[22][23]

Thomas Toon has suggested that if the population of Roman Lowland Britain was bilingual in both Brittonic and Latin, such a multilingual society might adapt to the use of a third language, such as that spoken by the Germanic Anglo-Saxons, more readily than would a monoglot population.[24]

Debate on the reason for the Brittonic language's miniscule influence on English

Summarize

Perspective

Old English shows little obvious influence from Celtic: there are vanishingly few English words of Brittonic origin.[12][13][27] Latin loanwords into early Old English were more numerous; since they were part of a continuous process of borrowing from Latin into Germanic languages, it is hard to be sure how many belong to the early Old English period, but they number in the tens or hundreds.[28][29][30][31]

Demographic Replacement Theory

The traditional explanation for the lack of Celtic influence on English, supported by uncritical readings of the accounts of Gildas and Bede, is that Old English became dominant primarily because Germanic-speaking invaders killed, chased away, and/or enslaved the previous inhabitants of the areas that they settled, particularly in the East. A number of specialists maintained support for such explanations into the 21st century,[32][33] and variations on this theme continued to feature in standard histories of English.[34][35][36][37] Peter Schrijver said in 2014 that "to a large extent, it is linguistics that is responsible for thinking in terms of drastic scenarios" about demographic change in late Roman Britain.[38]

Elite acculturation

The development of contact linguistics in the later 20th century, which involved study of present-day language contact in well-understood social situations, gave scholars new ways to interpret the situation in early medieval Britain. Meanwhile, archaeological and genetic research suggest that a complete demographic change is unlikely to have taken place in 5th-century Britain.

Thus, a contrasting model of elite acculturation has been proposed in which a politically dominant but numerically insignificant number of Old English speakers drove large numbers of Britons to adopt Old English. In that theory, if Old English became the most prestigious language in a particular region, speakers of other languages there would have sought to become bilingual, and over a few generations, they stopped speaking the less prestigious languages (in this case, British Celtic and/or British Latin). If Old English became the most prestigious language in a particular region, speakers of other languages may have found it advantageous to become bilingual and, over a few generations, stop speaking the less prestigious languages. Similar culture changes are observed in observed in early medieval Russia, North Africa and some other parts of the Islamic world, where a politically and socially powerful minority culture becomes, over a rather short period, adopted by a settled majority.[39] The collapse of Britain's Roman economy seems to have left Britons living in a society technologically similar to that of their Anglo-Saxon neighbours, which made it unlikely that Anglo-Saxons would need to borrow words for unfamiliar concepts.[40]

Sub-Roman Britain saw a greater collapse in Roman institutions and infrastructure, compared to the situation in Roman Gaul and Hispania, perhaps especially after 407 AD, when it is probable that most or all of the Roman field army stationed in Britain was withdrawn to support the continental ambitions of Constantine III. That would have led to a more dramatic reduction in the status and prestige of the Romanised culture in Britain, and so the incoming Anglo-Saxons had little incentive to adopt British Celtic or Latin, and the local people were more likely to abandon their languages in favour of the then-higher-status language of the Anglo-Saxons.[41]In Higham's assessment, "language was a key indicator of ethnicity in early England. In circumstances where freedom at law, acceptance with the kindred, access to patronage, and the use or possession of weapons were all exclusive to those who could claim Germanic descent, then speaking Old English without Latin or Brittonic inflection had considerable value".[42] In those circumstances, it is plausible that Old English would borrow few words from the lower-status language(s).[43][44]

The adoption of Germanic languages by status seeking Britons[45] could in turn lead to a 'retrospective reworking' of kinship ties to the dominant group ultimately leading to the "myths which tied the entire society to immigration as an explanation of their origins in Britain".[46]

Elite personal names

One piece of evidence for elite acculturation has been the Celtic names of members of the Anglo-Saxon elite

Textual sources hint that people who are portrayed as ethnically Anglo-Saxon actually had British connections:[47] the West Saxon royal line was supposedly founded by a man named Cerdic, whose name derives from the Brittonic Caraticos (cf. Welsh Ceredig),[48][49][50] whose supposed descendants Ceawlin[51] and Caedwalla (d. 689) also had Brittonic names.[52] The British name Caedbaed is found in the pedigree of the kings of Lindsey.[53] The names of King Penda and some other kings of Mercia have more obvious Brittonic than Germanic etymologies, but they do not correspond to known Welsh personal names.[54][55] The early Northumbrian churchmen Chad of Mercia (a prominent bishop) and his brothers Cedd (also a bishop), Cynibil and Caelin, along with the supposed first composer of Christian English verse, Cædmon, also have Brittonic names.[56][57]

It has been pointed out that there was conspicuously no attempt by contemporary British or Anglo-Saxons genealogists to give British and Anglo-Saxon royal families a common ancestry, in contrast to the practice of Anglo-Saxon genealogies intermeshing around claimed common descent from Woden or Welsh genealogies intermeshing in a supposed common descent from the fourth-century Romano-British imperial claimant Magnus Maximus.[58]

Criticisms of Elite Acculturation

Critics of elite acculturation point out that in most cases, minority elite classes have not been able to impose their languages on a settled population.[59][33][60] Furthermore, the archaeological and genetic evidence has cast doubt upon theories of expulsion and ethnic cleansing but also has tended not to support the idea that the extensive change seen in the post-Roman period was simply the result of acculturation by a ruling class. In fact, many of the initial migrants seem to have been families, rather than warriors, with significant numbers of women taking part and elites not emerging until the sixth century.[61][62][63][64]

In light of that, the emerging consensus among historians, archaeologists and linguists is that the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain was not a single event and thus cannot be explained by any one particular model. In the core areas of settlement in the south and east, for example, large-scale migration and population change seem to be the best explanations.[65][66][67][68][69] In the peripheral areas to the northwest, on the other hand, a model of elite dominance may be the most fitting.[64][70] In that view, therefore, the decline of Brittonic and British Latin in England can be explained by a combination of migration, displacement and acculturation in different contexts and areas.[64][71][72]

Question of detecting substratal Celtic influence on English

| Features | Coates [73] |

Miller [74] |

Hickey [75] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two functionally distinct "to be" verbs | ✔ * | ✔ | ✔ |

| Northern subject rule * | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Development of reflexives | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Rise of progressive | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Loss of external possessor | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Rise of the periphrastic "do" | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Negative comparative particle * | ✔ | ||

| Rise of pronoun -en ** | ✔ | ||

| Merger of /kw-/, /hw-/ and /χw-/ * | ✔ | ||

| Rise of "it" clefts | ✔ | ||

| Rise of sentential answers and tagging | ✔ | ||

| Preservation of θ and ð | ✔ | ||

| Loss of front rounded vowels | ✔ |

* regional, northern England; ** regional, southwestern England

Supporters of the acculturation model in particular must account for the fact that in the case of a fairly swift language shift, involving second-language acquisition by adults, the learners' imperfect acquisition of the grammar and the pronunciation of the new language will affect it in some way. As yet, there is no consensus that such effects are visible in the surviving evidence in the case of English. Thus, one synthesis concluded that 'the evidence for Celtic influence on Old English is somewhat sparse, which only means that it remains elusive, not that it did not exist'.[76]

Although there is little consensus about the findings, extensive efforts have been made during the 21st century to identify substrate influence of Brittonic on English.[77][78][79][80][81]

Celtic influence on English has been suggested in several forms:

- Phonology. Between c. 450 and c. 700, Old English vowels underwent many changes, some of them unusual (such as the changes known as 'breaking'). It has been argued that some of these changes are a substrate effect caused by speakers of British Celtic adopting Old English during that period.[82]

- Morphology. Old English morphology underwent a steady simplification during the Old English period and beyond into the Middle English period. That would be characteristic of influence by an adult-learner population. Some simplifications that become visible only in Middle English may have entered low-status varieties of Old English earlier but appeared in higher-status written varieties only at the late date.[83][84]

- Syntax. Over centuries, English has gradually acquired syntactic features in common with Celtic languages (such as the use of 'periphrastic "do" ').[85] Some scholars have argued that they reflect early Celtic influence, which, however, became visible in the textual record only later on. Substrate influence on syntax is considered especially likely during language shifts.[86]

However, various counter-arguments have been proposed:

- The sound changes in Old English bear no clear resemblance to any that occurred in Brittonic,[87] and phenomena similar to 'breaking' have been found in Old Frisian and Old Norse.[88] Other scholars have proposed that the changes were the result of dialect contact and levelling among Germanic speakers in the period following their settlement.[89][90]

- There is no evidence for a Celtic-influenced low status variety of English in the Anglo-Saxon period (in comparison, the lingua romana rustica is referenced in Gaulish sources).[91][92]

- It has been argued that the geographical patterns of morphological simplification make little sense when they are viewed as a Brittonic influence, but match perfectly with areas of Viking settlement, which suggests that contact with Old Norse is the more likely reason for the change.[93][94]

- Syntactical features in English that resemble those found in modern Celtic languages did not become common until the Early Modern English period. It has been argued that that is far too late of an appearance for substrate features, and thus they are most likely internal developments, or possibly later contact influences.[95]

- The English features and the Celtic ones from which they are theorised to have originated often do not have clear parallels in usage.[96]

Coates has concluded that the strongest candidates for potential substrate features can be seen in regional dialects in the north and the west of England (roughly corresponding to Area 3 in Jackson's chronology), such as the Northern Subject Rule.[97]

Contrast with Continental experiences

The contrast to experience in places post-Roman Gaul where the invaders adopted the Latin derived languages of the local population has been suggested by Bryan Ward-Perkins to have been due to the successful native resistance of local, militarised tribal societies to the invaders may perhaps account for the fact of the slow progress of Anglo-Saxonisation as opposed to the sweeping conquest of Gaul by the Franks.[98]

Pre-Existing Germanic settlement thesis

One idiosyncratic explanation for the spread of English that gained extensive popular attention was Stephen Oppenheimer's 2006 suggestion that the lack of Celtic influence on English was caused by the ancestor of English being already widely spoken in Britain by the Belgae before the end of the Roman period.[99] However, Oppenheimer's ideas have not been found helpful in explaining the known facts since there is no solid evidence for a well established Germanic language in Britain before the fifth century (among the Belgae or otherwise) and the idea contradicts the extensive evidence for the use of Celtic and Latin.[100][101]

Likewise, Daphne Nash-Briggs speculated that the Iceni might have been at least partially Germanic-speaking. In her view, their tribal name and some of the personal names found on their coins have more obvious Germanic derivations than Celtic ones.[102] Richard Coates has disputed this assertion by arguing that while a satisfactory Celtic derivation for the tribal name has not been reached, it is "clearly not Germanic."[103]

Debate on why are there so few etymologically Celtic place-names in England

Summarize

Perspective

Place-names are traditionally seen as important evidence for the history of language in post-Roman Britain for three main reasons:

- It is widely assumed that even when first attested later, names were often coined in the settlement period.

- Although it is not clear who in society determined what places were called, place-names may reflect the usage of a broader section of the population than written texts.

- Place-names provide evidence for language in regions for which we lack written sources.[105]

Post-Roman place-names in England begin to be attested from around 670, pre-eminently in Anglo-Saxon charters;[106] they have been intensively surveyed by the English and the Scottish Place-Name Societies.

Except in Cornwall, the vast majority of place-names in England are easily etymologised as Old English (or Old Norse from later Viking influence), which demonstrates the dominance of English across post-Roman England. That is often seen as evidence for a cataclysmic cultural and demographic shift at the end of the Roman period in which not only the Brittonic and Latin languages but also Brittonic and Latin place-names and even Brittonic- and Latin-speakers were swept away.[32][33][107][108]

From around the 1990s, research on Celtic toponymy, driven by the development of Celtic studies and particularly by Andrew Breeze and Richard Coates, has complicated that picture. More names in England and southern Scotland have Brittonic or occasionally Latin etymologies than was once thought.[109] Earlier scholars often did not notice that because they were unfamiliar with Celtic languages. For example, Leatherhead was once etymologised as Old English lēod-rida, meaning "place where people [can] ride [across the river]".[110] However, lēod has never been discovered in place-names before or since, and *ride 'place suitable for riding' was merely speculation. Coates showed that Brittonic lēd-rïd 'grey ford' was more plausible.[111] In particular, there are clusters of Cumbric place-names in northern Cumbria[15] and to the north of the Lammermuir Hills.[112] Even so, it is clear that Brittonic and Latin place-names in the eastern half of England are extremely rare; although they are noticeably more common in the western half, they are still a tiny minority: 2% in Cheshire, for example.[113]

Likewise, some entirely Old English names explicitly point to Roman structures, usually using Latin loan-words or to the presence of Brittonic-speakers. Names like Wickham clearly denoted the kind of Roman settlement known in Latin as a vicus, and others end in elements denoting Roman features, such as -caster, denoting castra ('forts').[114] There is a substantial body of names along the lines of Walton/Walcot/Walsall/Walsden, many of which must include the Old English word wealh in the sense 'Celtic-speaker',[115][116] and Comberton, many of which must include Old English Cumbre 'Britons'.[117] Those are likely to have been names for enclaves of Brittonic-speakers but again are not that numerous.

Some scholars have stressed that Welsh and Cornish place-names from the Roman period seem no more likely to survive than Roman names in England: 'clearly name loss was a Romano-British phenomenon, not just one associated with Anglo-Saxon incomers'.[118][119] Therefore, other explanations for the replacement of Roman period place-names which allow for a less cataclysmic shift to English naming include:

- Adaptation rather than replacement. Names that came to look as if they were coined as Old English may actually come from Roman ones. For example, the Old English name for the city of York, Eoforwīc (earlier *Eburwīc), transparently means 'boar-village'. We know that the first part of the name was borrowed from the earlier Romanised Celtic name Eburacum only because that earlier name is one of relatively few Roman British place-names that were recorded. Otherwise, we would have assumed that the Old English name was coined from scratch. (Likewise, the Old English name was, in turn, adapted into Norse as Jórvík, which transparently means 'horse-bay', and again, it would not be obvious that was based on an earlier Old English name if that had not been recorded.)[120][121][122][123][124]

- In addition, several plausibly Brittonic place- and river-names in Northern and Midland England appear to have their naming elements at least partly replaced by Old English, Old Norse and French ones, and in some cases, the older forms appear on historical record. Such names include Alkincoats, Beverley, Binchester, Blindbothel, Brailsford, Cambois, Carrycoats, Derby, Drumburgh (< Drumboch), Fontburn, Gilcrux, Glenridding, Lanchester, Lichfield, Mancetter, Manchester, Penshaw (< Pencher), Towcett, Tranewath and Wharfe.[125][126][127]

- Invisible multilingualism. Place-names that survive only in Old English form may have had Brittonic counterparts for long periods without those being recorded. For example, the Welsh name of York, Efrog, derives independently from the Roman Eboracum, and other Brittonic names for English places might also have continued in parallel to the English ones.[128][129][130]

- In addition, several toponyms are still known by both Celtic and English names, such as Blencathra/Saddleback and Catlowdy/Lairdstown. Other non-Celtic place-names with recorded medieval era British Celtic forms include Bamburgh (Din Guoaroy), Bristol (Caer Odor), Brokenborough (Kairdurberg), Maiden Castle (Carthanacke) and Nantwich (Hellath-Wen) as well as, more speculatively, Lodore Falls (Rhaeadr Derwennydd), Nottingham (Tigguocobauc).[125][127]

- During the Romano-British era (43-410 AD), several places that now have English names were recorded with Celtic-derived ones. This includes Birdoswald (Banna), Castleshaw (Rigodunum), Chesterholme (Vindolanda), Ebchester (Vindomora), Rudchester (Vindobala), Stanwix (Uxelodunum), Whilton Lodge (Bannaventa) and Whitley Castle (Epiacum).[125]

- Some Welsh names for places in England may have ancient etymologies independent of the English forms, this includes the Welsh name for Shrewsbury (Amwythig).[131]

- Some settlement names may contain earlier Celtic names for rivers that now have English or Norse ones. Such settlement names include Auckland, Dacre, Cark, Hailes, Leeds (with Ledsham and Ledston), Penrith and Tintwistle.[125][127]

- Misleading later evidence. Later evidence for place-names may not be as indicative of naming in the immediate post-Roman period as was once assumed. In names attested up to 731, 26% are etymologically partly non-English,[132] and 31% have since fallen from use.[133] Settlements and land tenure may have been relatively unstable in the post-Roman period, leading to a high natural rate of place-name replacement and enabling names coined in the increasingly-dominant English language to replace names inherited from the Roman period relatively swiftly.[134][135]

- Archaeological evidence suggests that, during the immediate post-Roman period of the 5th century, Iron Age and Roman era fortifications were usually not kept in use south of Hadrian's Wall, which may be associated with many Roman-era fort names falling out of use.[125]

Thus, place-names are important for showing the swift spread of English across England and also provide important glimpses into details of the history of Brittonic and Latin in the region,[7][17] but they do not demand a single or simple model for explaining the spread of English.[134]

Twenty-first-century research

Extensive research is ongoing on whether British Celtic did exert subtle substrate influence on the phonology, morphology, and syntax of Old English[136] These arguments have not yet, however, become consensus views. Thus a 2012 synthesis concludes that 'the evidence for Celtic influence on Old English is somewhat sparse, which only means that it remains elusive, not that it did not exist'.[137]

Debate continues within a framework assuming that many Brittonic-speakers shifted to English, for example over whether at least some Germanic-speaking peasant-class immigrants must have been involved to bring about the language-shift; what legal or social structures (such as enslavement or apartheid-like customs) might have promoted the high status of English; and precisely how slowly Brittonic (and British Latin) disappeared in different regions.

See also

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.