Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Can You Hear Their Voices?

1931 play by Hallie Flanagan and Margaret Ellen Clifford From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Can You Hear Their Voices? A Play of Our Time[2] is a 1931 play by Hallie Flanagan and her former student Margaret Ellen Clifford, based on the short story "Can You Make Out Their Voices" by Whittaker Chambers. The play premiered at Vassar College on May 2, 1931,[1] and ran most recently Off Broadway June 3–27, 2010. Broadway World notes that it anticipated John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath and Clifford Odets' Waiting for Lefty, predating them by eight years and by four years respectively.[3]

Remove ads

Remove ads

Significance

Summarize

Perspective

This play is one of the earliest examples of Political theatre in the U.S. It also is a forerunner of the "Living Newspaper" theatrical form in the U.S.--which Flanagan herself championed as head of the Federal Theatre Project later in the decade.[4] "Can You Hear Their Voices, which Flanagan produced in Vassar's experimental theater, became the prototype for Living Newspapers."[4]

Chambers described the story's immediate impact in his memoirs:

It had a success far beyond anything that it pretended to be. It was timely. The New York World-Telegram spotted it at once and wrote a piece about it. International Publishers, the official Communist publishing house, issued it as a pamphlet.[5] Lincoln Steffens hailed it in an effusion that can be read in his collected letters. Hallie Flanagan, then head of Vassar's Experimental Theater, turned it into a play.[6]

In February 1932, the Vassar Miscellany News stated that since its opening only a few months before "the fame of this propaganda play has spread not only throughout America, but over Europe and into Russia, China, and Japan. The amount of enthusiasm which the play has evoked has been unexpected and exciting, starting, as it did, from an amateur performance." Beyond its timeliness, the newspaper noted a general widespread appeal, such that "letters from Vancouver to Shanghai" asked for rights to produce the play... The News Masses was already selling the play in book format for Germany, Denmark, France, and Spain, with special copies sent to the International Bureau of Revolutionary Literature in Russia, Greek and Hungarian workers clubs, a Yiddish theatrical group, a Finnish bookstore, and somewhere in Australia.[7]

In fact, the New Masses had reviewed the play and started advertising for its sale in book form in its June 1931 issue twice near the end of that issue[8] and then moved its advertisement to the front for July 1931.[9]

In 2010, Broadway World noted: "Chambers' true tale of desperate tenant farmers inspired a play that was ahead of its time: it predates John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath by eight years and Clifford Odets' Waiting for Lefty by four.[3]

Remove ads

Translations

According to Chambers, "In a few months, the little story had been translated even into Chinese and Japanese and was being played in workers' theaters all over the world."[6]

In 1931, Nathaniel Buchwald translated the play into Yiddish as Trikenish ("Drought").[10] In November 1931, ARTEF performed the Yiddish-language play, directed by Beno Schneider, at the Heckscher Theatre on Fifth Avenue at 104 Street.[11]

According to the Vassar Miscellany News, by early 1932 "By this date, translations had already appeared in Japanese, Yiddish, German, French, and Russian "with immediate prospects of translation into Chinese, and possibly Spanish and other languages."[7]

Remove ads

Background

The short story "Can You Make Out Their Voices" first appeared in the March 1931 issue of New Masses magazine.[12] Chambers said that he wrote the story in a single night. It received immediate coverage in the New York World-Telegram.[6]

Flanagan herself later called it "one of the great American short stories."[13]

Among the story's earliest readers was Flanagan's former student, Margaret Ellen Clifford (later chair of Drama at Skidmore College, 1952-1971.[14]) According to Flanagan, the two of them finished the scenario for a stage version in one night. Vassar library staff and journalism students contributed research, while her drama students helped with the writing.[15]

Plot synopsis

Summarize

Perspective

Short story

"Can You Make Out Their Voices" derives from a news story in January 1931 about tenant farmers in Arkansas, who raided a local Red Cross office to feed themselves. Chambers picked up on a common fear of the moment, namely, that this event marked the beginning of further popular uprisings in the face of drought and depression. In his story, the farmers have in their midst a quiet, dignified man—a communist—who unites them so that they take food by gunpoint, opposing the town's top businessman (a local banker, no less—a typical fat cat).

Chambers had been editing the Daily Worker newspaper for several years and wanted to stop writing "political polemics, which few people ever wanted to read." Instead, he wanted to write "stories that anybody might want to read—stories in which the correct conduct of the Communist would be shown in action and without political comment."[6]

Play

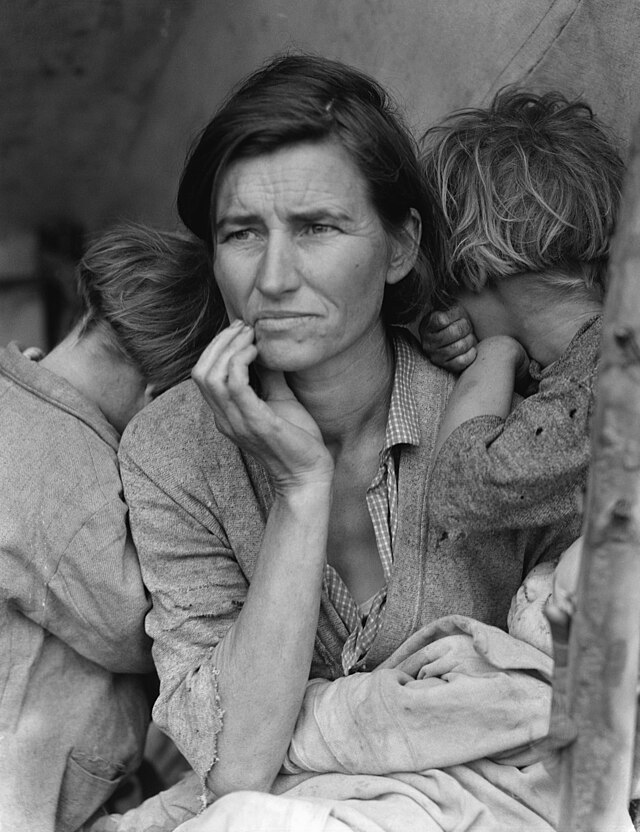

Can You Hear Their Voices? keeps much of the short story intact. It relates the effects of the first year of the Dust Bowl (and the second year of the Great Depression) on the farmers of a small town in rural Arkansas. Interjecting into this story are scenes in Washington, DC, that show a spectrum of reactions to the plight of those farmers.

Flanagan added the Washington angle as new material. She also changed the short story's outcome in Arkansas from armed to non-violent confrontation—which Chambers had actually added in the first place, since the actual event itself was non-violent. In so doing, she changed the approach from Chambers' call to Communism to a call to stop Communism. "Chambers had presented a problem with a communist solution. Hallie and Margaret Ellen gave no solution. Instead, they ended their play with a question, Can you hear what the farmers are saying, and what will you do about it."[16]

Remove ads

Production details

Summarize

Perspective

Theatrical runs

By 1932, Flannagan, Clifford, and Chambers had all offered productions of the play free to "workers groups."[7]

From Japan, director Seki Sano wrote on behand of the Japanese Proletarian Theatre League for permission to translate and perform the play at the Tokyo Left Theatre and other theatres: some 35,000 Japanese workers saw the play.[7]

Chronology

- May 2, 1931: Experimental Theatre of Vassar College, directed by Flanagan: "The drama was presented without an intermission; lighting was used to indicate scene changes, while statistics and newspaper reports were flashed on a screen onstage and placed throughout the lobby."[1][7][15]

- Between May 1931 and February 1932:

- Ford Hall Forum (Boston)[7]

- Hedgerow Theatre (Philadelphia)[7][15]

- Smith College (Northampton, Massachusetts)[7][15]

- Artef Theatre (New York City)[7]

- Cleveland Play House (Cleveland, Ohio)[7][17]

- Vineyard Shore School (West Park-on-the-Hudson, New York)[7][15]

- Commonwealth College (Mena, Arkansas)[7]

- Shanghai People's Theater (Shanghai, China)[6][7][15]

- (Tokyo Left Theatre) (Japan)[6][7]

- October 30-November 21, 2004: Steep Theatre (Chicago, Illinois)[18]

- June 3-June 27, 2010: Pop-Up Theater by the Obie Award-winning Peculiar Works Project (New York, New York)[19][20]

Details of 1931 theatrical run

The Vassar Miscellany News covered the play's opening on May 2, 1931.[1]

Cast

Details of 2010 theatrical run

Billing

- "Can You Hear Their Voices? (a play of our time)": title

- "by Hallie Flanagan and Margaret Ellen Clifford": adaptation

- "from a short story by Whittaker Chambers": author

Production

- Ralph Lewis: co-director[23]

- Barry Rowell: co-director[23]

- David Castaneda: lighting[24]

- Nikolay Levin: sets

- Deb O: costumes[25]

- Gwen Orel: dramaturg[26]

- Matthew Tennie: projection[27]

- Seth Bedford: music[28]

- Peculiar Works Project: archival video[29]

- Ryan Holsopple: sound[30]

- Marte Johanne Ekhoougen: props

- Cathy Carlton: production associate/swing actor

Set and light crew included: Christoper Hurt, Janet Bryant, Dror Shnayer, Diana Byrne, Tricia Byrne, and Skip LaPlante.

Video came from The Plow That Broke the Plains by Pare Lorentz, Universal Pictures newsreels, Reaching for the Moon by Edmund Goulding, Champagne (film) by Alfred Hitchcock, and Rain for the Earth by Clair Laning/Works Progress Administration.

Duration is about 70 minutes.

Cast (in order of speaking)

- Ben Kopit: Frank, Bill[31]

- Derek Jamison: Davis, ensemble[32]

- Catherine Porter: Ann, ensemble[23]

- Christopher Hurt: Wardell, ensemble[33]

- Ken Glickfield: Sam, Congressman Bagehot[34][35]

- Carrie McCrossen: John, ensemble[36]

- Tonya Canada: Doscher, Harriet[37]

- Rebecca Servon: Rose, ensemble[38]

- Mick Hilgers: Drdla, ensemble[39]

- Patricia Drozda: Purcell, ensemble[35]

- Sarah Elizondo: Hilda, ensemble[40]

Orchestra

- Aaron Dai: piano

- Brian Mark: clarinet

- Samuel C. Nedel: bass

Reviews

1930s Reviews

Flanagan's changes (cited under "Differences," above) are reflected in critical responses in the press:

- Poughkeepsie Sunday Courier (May 3, 1931): "If a certain crusading congressman could have seen last night's production he would have probably branded the whole company as dangerous, if not Red agitators."[41]

- Vassar Miscellany News (May 6, 1931): "With restrained yet powerful acting, the cast carried the audience from the drab hopelessness of life in the drought-stricken areas to the extravagant, gay (shall we say, voluptuous) carelessness of social life at the Capitol, and back again... It would be difficult to pick out a climax in the play, unless it is, perhaps, the moment at which Hilda Francis (Amdie von Behr, who, by the way, did one of the finest pieces of acting of the veiling) smothers her baby to keep her from starvation... But, for the most part, the play was too tense, too fast-moving, too well acted to give one time to stop feeling and think. The effectiveness with which the producers secured the desired emotional sweep was, in my opinion, one of its chief merits. Another much to be commended feature of the performance was the absolute unity achieved throughout the play in spite of the constant shifting between two such sharply contrasted backgrounds..."[1]

- The New York Times (May 10, 1931): "a searing, biting, smashing piece of propaganda"[15]

- Theatre Guild Magazine (July 1931): "frankly propagandist play... (that) deeply moved its audiences."[15][42]

- Theatre Arts Monthly (undated, probably 1931): "a good play, of important native material, well characterized, handling experimental technical material skillfully, worth any theatre's attention--amateur or professional."[15]

- Workers' Theatre (January 1932): "Flanagan and Clifford mutilated the class line of the story and adapted it into a play form with a clear liberal ideology."[15]

2010s Reviews

Change in times leads many reviewers to overlook key elements in story and style:

- New York Theater Wire (June 2, 2010): "This production is a reminder that clever staging and theatre with aural, spatial, and performance ingenuity aren't the exclusive province of the big budget."[43]

- New York Theatre (June 5, 2010): "The play itself feels dated and stiff, very much an artifact of a period when American dramatists were only starting to find their native voice and learn to tell stories of our country with depth and texture. But the history it recounts—for it is based, we are told, on actual events—is eminently worth remembering. And it's easy to understand why the good people at Peculiar Works Project have chosen to bring it to the stage at this particular moment, for the parallels between then and now are pretty clear."[44]

- Theater Mania (June 7, 2010): "There's a refreshingly -- and appropriate -- homespun quality to the Peculiar Works Project's revival of Hallie Flanagan and Margaret Ellen Clifford's Can You Hear Their Voices?"[45]

- Variety (magazine) (June 7, 2010): "high marks for research and a flunking grade for presentation"[27]

- BackStage (June 7, 2010): "without the pedigree of co-author Hallie Flanagan, famed as the head of the New Deal's four-year Federal Theatre Project (and memorably incarnated by Cherry Jones in the 1999 film "Cradle Will Rock"), there's little reason to excavate this dated play"[46]

- Village Voice (June 8, 2010): "Peculiar Works' production, impressively elaborate for such threadbare circumstances, tends to push the ideas at you heavily, but a genuine faith in the work's immediate relevance dignifies the pushing."[47]

- Show Business Weekly (June 8, 2010): "This brisk production, under Ralph Lewis and Barry Rowell’s direction, brings Chambers’s story to life with live music and projections of Depression-era footage by Matthew Tennie that smooth the transition between scenes. Deb O’s period costumes expertly evoke the era and add depth to Nikolay Levin’s minimal set, which uses platforms to make the best of its site-specific location. The cast consistently performs as a well-integrated ensemble, with all the actors playing extras in addition to their main roles. Their energetic performances have that rousing quality, which is so essential to the genre."[48]

- The New York Times (June 11, 2010): "Though “Can You Hear Their Voices?” is often more interesting than exciting, the script holds up surprisingly well. The scrappy Peculiar Works Project, which specializes in bringing theater to alternative sites, has made an intriguing move in reviving the story. And they've picked an intriguing time to tell it."[49]

- Stage Grade (undated): "...for many critics, this topical urgency isn't enough to excuse what they see as poor casting, acting, design, and direction choices... most find the production a trifle too academic or amateurish."[50]

- Theater Online (undated): "PWP’s production of Voices in the vacant storefront at 2 Great Jones Street in Noho fits perfectly with the company’s long-standing mission to “wake up” non-theater sites for theatrical performance."[51]

Characters

- Jim Wardell, farmer

- Ann Wardell, his wife

- John Wardell, 14-year-old son

- Sam Wardell, 12-year-old son

- Frank Francis, a young farmer

- Hilda Francis, his wife

- Mort Davis, an old farmer

- Dirdla, a Russian farmer

- Rose, his 18-year-old daughter

- Ms. Smythe, radio announcer

- Mr. Wordsworth, radio commentator

- Purcell, a rich local businessman

- Bagehot, a congressman

- Harriet, his debutante daughter

- Mrs. Martin, a neighbor

- Mary, her daughter

- Mrs. Doscher, another neighbor

- First Girl

- First Boy

- Second Girl

- Second Boy

- Third Girl

- Third Boy

- First Dowager

- Second Dowager

- Senator

- Another Senator

- Ambassador

- Painted Woman

- Young Attache

- Bill, Harriet's debutante ball date

- Governor Lee

- Red Cross Worker

Remove ads

Legacy

Vassar College houses a number of artifacts from and information about the play:

- Philalelatheis

- Documentary Chronicle: May 2, 1931

- Experimental Theatre

- Manuscripts

- Finding Aids

- "Audience Held by Propaganda Play" in Vassar Miscellany News (May 6, 1931)

- "Through the Campus Crates" in Vassar Quarterly (July 1, 1931)

- "Vassar Drama Arouses World-wide Interest," Vassar Miscellany News (February 24, 1932)[7]

Remove ads

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads