Loading AI tools

Clothing of the people in biblical times From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The clothing of the people in biblical times was made from wool, linen, animal skins, and perhaps silk. Most events in the Hebrew Bible and New Testament take place in ancient Israel, and thus most biblical clothing is ancient Hebrew clothing. They wore underwear and cloth skirts.

Complete descriptions of the styles of dress among the people of the Bible is impossible because the material at hand is insufficient.[1] Assyrian and Egyptian artists portrayed what is believed to be the clothing of the time, but there are few depictions of Israelite garb. One of the few available sources on Israelite clothing is the Bible.[2]

The earliest and most basic garment was the ʿezor (/eɪˈzɔːr/ ay-ZOR, all pronunciations are approximate)[4] or ḥagor (/hɑːˈɡɔːr/ khə-GOR),[5] an apron around the hips or loins,[3] that in primitive times was made from the skins of animals.[1] It was a simple piece of cloth worn in various modifications, but always worn next to the skin.[3] Priests wore an ʿezor of linen known as a ephod.[3] If worn for mourning, it was called a saq.[3] The ʿizār worn by Muslims as an undergarment as part of the ihram clothing worn during the Hajj is a cognate of ʿezor; it is also a term still in use in Yemen.

When a belt or girdle held garments together, the cloth was also called an ʿezor or ḥagor.[1]

The ʿezor later became displaced among the Hebrews by the ketonet or tunic (/kəˈθoʊnɛθ/ kə-THAW-net,[7] translated into Greek as chitōn[8]) an undertunic,[1][3] corresponding most nearly to a long shirt.[8] The ketonet appears in Assyrian art as a tight-fitting undergarment, sometimes reaching only to the knee, sometimes to the ankle.[3]

In its early form, the ketonet was sleeveless and even left the left shoulder uncovered.[9] In time, men of leisure wore ketonet with sleeves.[9] In later times, anyone dressed only in the ketonet was described as naked[1] (1Samuel 19:24, Isaiah 20:2, 2Kings 6:30, John 21:7); deprived of it he would be absolutely naked.

The well-off might also wear a ṣādin (/sɔːˈðiːn/ saw-DHEEN)[10] under the ketonet. This long undergarment had sleeves[8] and was of fine linen.[3]

The simlā (שִׂמְלָה /simˈlɔː/ seem-LAW),[11][12] was the heavy outer garment or shawl of various forms.[3] It consisted of a large rectangular piece of rough, heavy woolen material, crudely sewed together so that the front was unstitched and with two openings left for the arms.[1][3] Flax is another possible material.[1] It is translated into Koine Greek as "himation" (ἱμάτιον, /hɪˈmæti.ɒn/ hi-MOT-ee-on),[13] and the ISBE concludes that it "closely resembled, if it was not identical with, the himation of the Greeks."[8]

During the day, it was protection from rain and cold, and at night when traveling Israelites could wrap themselves in this garment for warmth on their journey during the Three Pilgrimage Festivals of Deuteronomy 16:16.[1][3] (see Deuteronomy 24:13). The front of the simlā also could be arranged in wide folds (see Exodus 4:6) and all kinds of products could be carried in it[1][3] (See 2Kings 4:39, Exodus 12:34).

Every respectable man generally wore a simlā over the ketonet (See Isaiah 20:2–3), but since the simlā hindered work, it was either left home or removed when working.[1][3] (See Matthew 24:18). From this simple item of the common people developed the richly ornamented mantle of the well-off, which reached from the neck to the knees and had short sleeves.[3]

The meʿil (/məʔˈiːl/ mə-EEL,[14] translated into Greek as stolḗ[15][8]) stands for a variety of garments worn over the undergarment like a cloak[1] (1Samuel 2:19, 1Samuel 15:27), but used only by men of rank or of the priestly order[8] (Mark 12:38, Luke 20:46, Luke 15:22). The me'ı̄l was a costly wrap (1Samuel 2:19, 1Samuel 18:4, 1Samuel 24:5, 1Samuel 24:11) and the description of the priest's meʿil was similar to the sleeveless bisht[3] (Exodus 28:31; Antiquities of the Jews, III. vii. 4). This, like the meʿil of the high priest, may have reached only to the knees, but it is commonly supposed to have been a long-sleeved garment made of a light fabric.[1]

At a later period the nobles wore over the simlā, or in place of it, a wide, many-folded mantle of state (adderet, /əˈdɛrɛθ/ ə-DERR-eth[16] or maʿṭāfā /mʌʔətɔːˈfɔː/ ə-DERR-eth) made of rich material (See Isaiah 3:22), imported from Babylon (Joshua 7:21).[1] The leather garment worn by the prophets was called by the same name because of its width.[3]

The Torah commanded that Israelites wear tzitzit, tassels or fringes (ṣiṣit, /tsiːˈtsiːt/ tsee-TSEET[17]) attached to the corners of garments (see Deuteronomy 22:12, Numbers 15:38–39).[1] Numbers 15:39 records that the tassels were to serve as reminders to keep the Lord's commandments.

Phylacteries or tefillin are boxes containing biblical verses attached to the forehead and arm by leather straps,[18] and were in use by the late Second Temple period (see Matthew 23:5).

Depictions show some Hebrews and Syrians bareheaded or wearing merely a band to hold the hair together.[3] Hebrew people undoubtedly also wore head coverings similar to the modern keffiyeh, a large square piece of woolen cloth folded diagonally in half into a triangle.[3] The fold is worn across the forehead, with the keffiyeh loosely draped around the back and shoulders, often held in place by a cord circlet. Men and women of the upper classes wore a kind of turban, cloth wound about the head. The shape varied greatly.[3]

The High Priest would've worn a particular kind of priestly turban. In the Second Temple period, many Jews would've worn a sudra.

Sandals (naʿelayim) of leather were worn to protect the feet from burning sand and dampness.[1] Sandals might also be of wood, with leather straps (Genesis 14:23, Isaiah 5:27).[3] Sandals were not worn in the house nor in the sanctuary[1][3] (see (Exodus 3:5), Joshua 5:15). To walk about without sandals was otherwise a sign of great poverty (Deuteronomy 25:9) or of mourning (2Samuel 15:30, Ezekiel 24:17,23).[1][3]

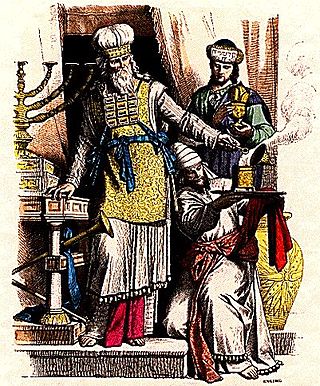

The Torah provides for specific vestments to be worn by the priests when they are ministering in the Tabernacle.[19] The high priest wore eight holy garments (bigdei kodesh). Of these, four were of the same type worn by all priests and four were unique to the high priest.

Those vestments which were common to all priests were the priestly tunic, priestly sash, priestly turban, and priestly undergarments.

The vestments that were unique to the high priest were the priestly robe, ephod (vest or apron), priestly breastplate, and priestly golden head plate.

In addition to the above "golden garments", the high priest also had a set of white "linen garments" (bigdei ha-bad) which he wore only on Yom Kippur for the Yom Kippur Temple service.[20]

While a woman's garments mostly corresponded to those of men: they wore simlā and ketonet, they also evidently differed in some ways from those of men[1][3] (see Deuteronomy 22:5). Women's garments were probably longer (compare Nahum 3:5, Jeremiah 13:22, Jeremiah 13:26, Isaiah 47:2), had sleeves (2Samuel 13:19), presumably were brighter colors and more ornamented, and also may have been of finer material.[1][3] Also worn by women was the ṣādin, the finer linen underdress (see Isaiah 3:23, Proverbs 22:24).[3]

Furthermore, mention is made of the miṭpaḥat, a kind of veil or shawl (Ruth 3:15). This was ordinarily just a woman's neckcloth. Other than the use by a bride or bride-to-be (Genesis 24:65), prostitutes (Genesis 38:14) and possibly others (Ruth 3:3), a woman did not go veiled (Genesis 12:14, Genesis 24:15), except for modesty (Genesis 24:65). According to ancient laws, it reached from the forehead, over the back of the head to the hips or lower, and was like the neckerchief of arab women and Jewish women today.[3]

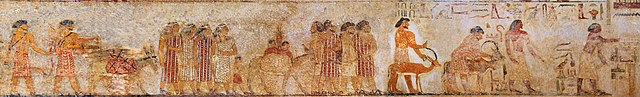

The Jews visited Egypt in the Bible from the earliest patriarchs (beginning in Genesis 12:10–20), to the flight into Egypt by Joseph, Mary, and the infant Jesus (in Matthew 2:13–23). The most notable example is the long stay from Joseph's (son of Jacob) being sold into slavery in Genesis 29, to the Exodus from Egypt in Exodus 14, during the Second Intermediate Period and New Kingdom. A large number of Jews (such as Jeremiah) also began permanent residence in Egypt upon the destruction of Jerusalem in 587 BC, during the Third Intermediate Period.

In Egypt, flax (linen) was the textile in almost exclusive use. The wool worn by Israelites was known, but considered impure as animal fibres were considered taboo. Wool could only be used for coats (they were forbidden in temples and sanctuaries). Egyptian fashion was created to keep cool while in the hot desert. People of lower class wore only the loincloth (or schenti) that was common to all. Slaves often worked naked. Sandals were braided with leather or, particularly for the bureaucratic and priestly classes, papyrus. Egyptians were usually barefoot. The most common headdress was the klafta or nemes, a striped fabric square worn by men.

Certain clothing was common to both genders, such as the tunic and the robe. Around 1425 to 1405 BC, a light tunic or short-sleeved shirt was popular, as well as a pleated skirt. Women often wore simple sheath dresses, and female clothing remained unchanged over several millennia, save for small details. Draped clothes, with very large rolls, gave the impression of wearing several items. Clothing of the royal family, such as the crowns of the pharaohs, was well documented. The pardalide (made of a leopard skin) was traditionally used as the clothing for priests.

Wigs, common to both genders, were worn by wealthy people of society. Made from real human and horse hair, they had ornaments incorporated into them.[21] Heads were shaved. Usually children were represented with one lock of hair remaining on the sides of their heads.

Heavy and rather voluminous jewelry was very popular, regardless of social class. It was made from turquoise, metals like gold and silver, and small beads. Both men and women adorned themselves with earrings, bracelets, rings, necklaces and neck collars that were brightly colored.

Greeks and Greek culture enters the Israelite world beginning with First Maccabees. Likewise the narrative of the New Testament (which was written in Greek) entered the Greek world beginning about Acts 13.

Clothing in ancient Greece primarily consisted of the chiton, peplos, himation, and chlamys. Despite popular imagination and media depictions of all-white clothing, elaborate design and bright colors were favored.[22] Greek clothing consisted of lengths of linen or wool fabric, which generally was rectangular. Clothes were secured with ornamental clasps or pins and a belt, sash, or girdle might secure the waist.

The inner tunic was a peplos or chiton. The peplos was worn by women. It was usually a heavier woollen garment, more distinctively Greek, with its shoulder clasps. The upper part of the peplos was folded down to the waist to form an apoptygma. The chiton was a simple tunic garment of lighter linen, worn by both genders and all ages. Men's chitons hung to the knees, whereas women's chitons fell to their ankles. Often the chiton is shown as pleated.

The chlamys was made from a seamless rectangle of woolen material worn by men as a cloak. The basic outer garment during winter was the himation, a larger cloak worn over the peplos or chiton. The himation has been most influential perhaps on later fashion.

The Roman general Pompey entered Jerusalem in 63 BC, ending Judean national independence. During the New Testament narrative, Judea was ruled by either local client kings to the Roman Empire or as a Roman province under Roman officials.

Probably the most significant item in the ancient Roman wardrobe was the toga, a one-piece woolen garment that draped loosely around the shoulders and down the body. Togas could be wrapped in different ways, and they became larger and more voluminous over the centuries. Some innovations were purely fashionable. Because it was not easy to wear a toga without tripping over it or trailing drapery, some variations in wrapping served a practical function. Other styles were required, for instance, for covering the head during ceremonies.

Magistrates and high priests wore a special kind of toga with a reddish-purple band on the lower edge, called the toga praetexta as an indication of their status. The toga candida, an especially whitened toga, was worn by political candidates. Prostitutes wore the toga muliebris, rather than the tunics worn by most women. The toga pulla was dark-colored and worn for mourning, while the toga purpurea, of purple-dyed wool, was worn in times of triumph and by the Roman emperor.

After the transition of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire in c. 44 BC, only men who were citizens of Rome wore the toga. Women, slaves, foreigners, and others who were not citizens of Rome wore tunics and were forbidden from wearing the toga. By the same token, Roman citizens were required to wear the toga when conducting official business. Over time, the toga evolved from a national to a ceremonial costume. Different types of togas indicated age, profession, and social rank.

Originally the toga was worn by all Romans; free citizens were required to wear togas because only slaves and children wore tunics.By the 2nd century BC, however, it was worn over a tunic, and the tunic became the basic item of dress. Women wore an outer garment known as a stola, which was a long pleated dress similar to the Greek chitons.

Many other styles of clothing were worn and also are familiar in images seen in artwork from the period. Garments could be quite specialized, for instance, for warfare, specific occupations, or for sports. In ancient Rome women athletes wore leather briefs and brassiere for maximum coverage but the ability to compete.

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.