Awakenings

1990 American drama film From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Awakenings is a 1990 American biographical drama film written by Steven Zaillian, directed by Penny Marshall, and starring Robert De Niro, Robin Williams, Julie Kavner, Ruth Nelson, John Heard, Penelope Ann Miller, Peter Stormare and Max von Sydow. It is based on Oliver Sacks's 1973 nonfiction memoir of the same title. The film tells the story of the fictional neurologist Dr. Malcolm Sayer (Williams), whose character is based on Sacks.

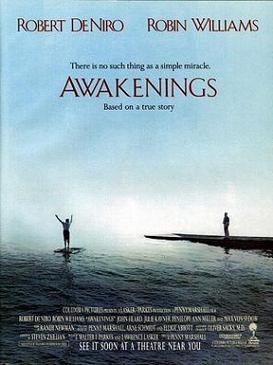

| Awakenings | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Penny Marshall |

| Screenplay by | Steven Zaillian |

| Based on | Awakenings by Oliver Sacks |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Miroslav Ondricek |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Randy Newman |

Production company | Lasker/Parkes Productions |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 121 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $29 million[1] |

| Box office | $108.7 million |

In 1969, Sayer discovers the beneficial effects of the drug L-DOPA and administers the drug to catatonic patients who survived the 1919–1930 epidemic of encephalitis lethargica. The patients—among them the focal character Leonard Lowe (De Niro)—are awakened after decades and must therefore try to acclimate to life in a new and unfamiliar time.

The film was produced by Walter Parkes and Lawrence Lasker, who first encountered Sacks's book as undergraduates at Yale University. Released on 12 December 1990, Awakenings was a critical and commercial success, earning $108.7 million on a $29 million budget. It was nominated for three Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Actor (De Niro), and Best Adapted Screenplay.

Plot

Summarize

Perspective

In 1969, Dr. Malcolm Sayer is a dedicated and caring physician at a local hospital in the New York City borough of the Bronx. After working extensively with the catatonic patients who survived the 1919–1930 epidemic of encephalitis lethargica, Sayer discovers that certain stimuli will reach beyond the patients' respective catatonic states. Actions such as catching a ball, hearing familiar music, being called by their name, and enjoying human touch, each have unique effects on particular patients and offer a glimpse into their worlds. Patient Leonard Lowe seems to remain unmoved, but Sayer learns that Leonard is able to communicate with him by using a Ouija board.

After attending a lecture at a conference on the drug L-DOPA and its success for patients with Parkinson's disease, Sayer believes that the drug may offer a breakthrough for his own group of patients. A trial run with Leonard yields astounding results; Leonard completely "awakens" from his catatonic state. This success inspires Sayer to ask for funding from donors, so that all the catatonic patients can receive the L-DOPA medication and gain "awakenings" to reality and the present.

Meanwhile, Leonard is adjusting to his new life, and becomes romantically interested in Paula, the daughter of another hospital patient. Leonard begins to chafe at the restrictions placed on him as a patient of the hospital, desiring the freedom to come and go as he pleases. He stirs up a revolt by arguing his case to Sayer and the hospital administration. As Leonard becomes more agitated, Sayer notices that a number of facial and body tics begin to manifest, which Leonard has difficulty controlling.

Although Sayer and the hospital staff are initially overjoyed by the success of L-DOPA in reviving a group of catatonic patients, they soon realize that the effects are only temporary. Leonard, the first to "awaken," is also the first to show signs of decline. His tics gradually worsen, his walk becomes a shuffle, and he begins experiencing full-body spasms that severely limit his movement. Despite the pain, Leonard remains resolute. He asks Sayer to film him, hoping his experience might one day contribute to research that helps others.

Aware of his deteriorating condition, Leonard shares a final lunch with Paula. He gently tells her that he can no longer see her, but before parting ways, she invites him to dance. Miraculously, his spasms cease for a brief, tender moment. Though Leonard and Sayer reconcile, Leonard soon slips back into a catatonic state. One by one, the other patients follow, despite increasing doses of L-DOPA.

Later, Sayer speaks to a group of hospital donors, explaining that while the physical awakenings were fleeting, a deeper awakening had occurred—a renewed sense of appreciation for life. He himself grows from the experience, finally overcoming his intense shyness to ask Nurse Eleanor Costello out for coffee, long after having once declined her invitation. The staff now treat the patients with greater empathy and dignity, and Paula continues to visit Leonard. Though Leonard is once again unresponsive, he and Sayer maintain their connection through the Ouija board, a quiet testament to the enduring human spirit.

Cast

- Robert De Niro as Leonard Lowe

- Robin Williams as Dr. Malcolm Sayer

- Julie Kavner as Eleanor Costello

- John Heard as Dr. Kaufman

- Penelope Ann Miller as Paula

- Max von Sydow as Dr. Peter Ingham

- Vincent Pastore as Ward #5 Patient #6

- Ruth Nelson as Mrs. Lowe

- Alice Drummond as Lucy

- Judith Malina as Rose

- George Martin as Frank

- Anne Meara as Miriam

- Mary Alice as Nurse Margaret

- Richard Libertini as Sidney

- Keith Diamond as Anthony

- Peter Stormare as neurochemist

- Bradley Whitford as Dr. Tyler

- Dexter Gordon as Rolando

Production

Summarize

Perspective

Casting

On September 15, 1989, Liz Smith reported that those being considered for the role of Leonard Lowe's mother were Kaye Ballard, Shelley Winters and Anne Jackson;[2] not quite three weeks later, Newsday named Nancy Marchand as the leading contender.[3] In January 1990 — more than three quarters of the way through the film's four-month shooting schedule[4][5][6] — the matter was seemingly resolved, when the February 1990 issue of Premiere magazine published a widely cited story, belatedly informing fans that, not only had Winters gotten the role, she had been targeted at De Niro's request, and had been cast by displaying her Oscar awards (for the benefit of veteran casting director, Bonnie Timmermann).[a]

Ms. Winters arrived, sat down across from the casting director and did, well, nothing. After a moment of silence, she reached into her satchel and pulled out an Oscar, which she placed on the desk. After another moment, she reached in and pulled out another, placing it on the desk beside the first.[b] Finally she said: "Some people think I can act. Do you still want me to read for this part?" "No, Miss Winters," came the reply. She got the part.[14]

Despite Liz Smith's, Newsday's and Premiere's seemingly definitive reports (which, minus any mention of the specific film being discussed, would be periodically reiterated and ultimately embellished in subsequent years),[15][16] the film was released in December 1990, featuring neither Winters (whose early dismissal evidently resulted from continuing attempts to pull rank on director Penny Marshall)[17][18] nor any of the other previously publicized candidates (nor at least two others, Jo Van Fleet and Teresa Wright, identified in subsequent accounts),[19][20] but rather the then-85-year-old Group Theater alumnus, Ruth Nelson, giving a well-received performance in what would be her final feature film.[21][19] "As Leonard's mother," wrote The Wall Street Journal critic, Julie Salamon, "Nelson achieves a wrenching beauty that stands out even among these exceptional actors doing exceptional things."[22] In her 2012 memoir, Penny Marshall recalled:

Ruth was a great lady. She was a New York stage actress in the 1930s who transitioned to movies but was blacklisted in the 1950s when her second husband was among those Senator Joseph McCarthy labeled a Communist. She was victimized by association and didn't work for three decades. When I met her, she was eighty-four and had battled a brain tumor and also had arthritis. I stared at her slender arms and gnarled hands. It looked like she had pushed her kid's arms and legs down for years. I liked her. I couldn't get her insured, but I didn't care. Neither did she. She wanted to do it. To me, that’s what the movie was about.[23]

Filming

Principal photography for Awakenings began on October 16, 1989, at the Kingsboro Psychiatric Center in Brooklyn, New York, which was operating, and lasted until February 16, 1990. According to Williams, actual patients were used in the filming of the movie.[24] In addition to Kingsboro, sequences were filmed at the New York Botanical Garden, Julia Richman High School, the Casa Galicia, and Park Slope, Brooklyn.[25]

Reception

Summarize

Perspective

Awakenings was released theatrically on December 12, 1990, with an opening weekend gross of $417,076,[26] opening in second place, behind Home Alone's ninth weekend, with $8,306,532.[27] It went on to gross $52.1 million in the United States and Canada,[26] and $56.6 million internationally,[28] for a worldwide total of $108.7 million.

Critical response

Awakenings received positive reviews from critics. Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 82% of 38 film critics have given the film a positive review, with an average rating of 6.6/10. Its consensus states: "Elevated by some of Robin Williams'[s] finest non-comedic work and a strong performance from Robert De Niro, Awakenings skirts the edges of melodrama, then soars above it."[29] Metacritic, which assigns a weighted average score from reviews of mainstream critics, gives the film a score of 74 out of 100, based on 18 reviews.[30] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore gave the film a grade of "A" on scale of A+ to F.[31]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film a rating of four stars out of four, writing,

After seeing Awakenings, I read [the book], to know more about what happened in that Bronx hospital. What both the movie and the book convey is the immense courage of the patients and the profound experience of their doctors, as in a small way they reexperienced what it means to be born, to open your eyes and discover to your astonishment that "you" are alive.[32]

Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly praised the film's performances, citing,

There's a raw, subversive element in De Niro's performance: He doesn't shrink from letting Leonard seem grotesque. Yet Awakenings, unlike the infinitely superior Rain Man, isn't really built around the quirkiness of its lead character. The movie views Leonard piously; it turns him into an icon of feeling. And so even if you're held (as I was) by the acting, you may find yourself fighting the film's design.[33]

Oliver Sacks, the author of the memoir on which the film is based, "was pleased with a great deal of [the film]", explaining,

I think in an uncanny way, De Niro did somehow feel his way into being Parkinsonian. So much so that sometimes when we were having dinner afterwards I would see his foot curl or he would be leaning to one side, as if he couldn't seem to get out of it. I think it was uncanny the way things were incorporated. At other levels I think things were sort of sentimentalized and simplified somewhat.[34]

Desson Howe of The Washington Post said that the film's tragic aspects did not live up to the strength in its humor, saying,

When nurse Julie Kavner (another former TV being) delivers the main Message (life, she tells Williams, is "given and taken away from all of us"), it doesn't sound like the climactic point of a great movie. It sounds more like a line from one of the more sensitive episodes of Laverne and Shirley.[35]

Similarly, Janet Maslin of The New York Times concluded her review by stating,

Awakenings works harder at achieving such misplaced liveliness than at winning its audience over in other ways.[36]

Accolades

The film was nominated for three Academy Awards, including: the Academy Award for Best Picture, the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, and the Academy Award for Best Actor (Robert De Niro). Robin Williams was also nominated at the 48th Golden Globe Awards for Best Actor in a Motion Picture Drama.

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipients | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | March 25, 1991 | Best Picture | Walter F. Parkes, Lawrence Lasker |

Nominated |

| Best Actor | Robert De Niro | Nominated | ||

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Steven Zaillian | Nominated | ||

| Awards of the Japanese Academy | March 20, 1992 | Best Foreign Film | Awakenings | Nominated |

| Chicago Film Critics Association Awards | 1991 | Best Actor | Robert De Niro | Nominated |

| Golden Globe Awards | January 19, 1991 | Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama | Robin Williams | Nominated |

| Grammy Awards | February 25, 1992 | Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or for Television | Randy Newman | Nominated |

| National Board of Review Awards | March 4, 1991 | Best Actor | Robert De Niro, Robin Williams (Tie) |

Won |

| Top Ten Films | Awakenings | Won | ||

| New York Film Critics Circle Awards | January 13, 1991 | Best Actor | Robert De Niro | Won |

| Writers Guild of America Award | March 20, 1991 | Best Adapted Screenplay | Steven Zaillian | Nominated |

Explanatory notes

- Neither as printed in the following 1990 Premiere excerpt nor as recounted by Winters herself six years later does this anecdote identify by name the casting director in question. As regards gender, however (and notwithstanding subsequent versions to the contrary), Winters's own account clearly cites a "casting lady",[7] and Bonnie Timmerman is indeed the credited casting director on the finished film.[8]

- At this point, a red flag regarding this story's accuracy should have been raised by any truly well-versed Winters fan, given the fact that roughly fifteen years earlier (as was widely reported, both at the time and subsequently), she had famously donated the first of her two Oscars to the Anne Frank Museum in Amsterdam.[9][10][11][12][13] Indeed, Winters' own version of events, as recounted to Tom Snyder in 1996, while failing to inform viewers that she did not in fact land the role in question, is accurate as regards both number of Oscars involved and gender—i.e. female—of both the film's unnamed "casting lady" and director Penny Marshall, towards whom, at least in retrospect, Winters displays a markedly greater degree of deference: "If Penny Marshall, who was the director, was going to ask me to read, that was okay with me."[7]

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.