Ateshgah of Baku

Fire Temple in Azerbaijan From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Ateshgah of Baku (Azerbaijani: Atəşgah), often called the "Fire Temple of Baku", is a castle-like religious temple in Surakhany town (in Surakhany raion),[2] a suburb in Baku, Azerbaijan.

| The Ateshgah at Surakhany, Baku | |

|---|---|

Azerbaijani: Atəşgah | |

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Ancient Syncretic (Zoroastrian/Hindu) Fire Temple, Mandir and Gurudwara[1] |

| Architectural style | Shirvan-Absheron architectural school |

| Location | Surakhany, Baku, Azerbaijan |

| Current tenants | Museum |

Based on Iranian and Indian inscriptions, the temple was used as a Hindu, Sikh, and Zoroastrian place of worship. "Ātash" (آتش/Atəş) is the Persian and Azerbaijani word for fire.[3] The pentagonal complex, which has a courtyard surrounded by cells for monks and a tetrapillar-altar in the middle, was built during the 17th and 18th centuries. It was abandoned in the late 19th century, probably due to the decline of the Indian population in the area and the establishment of petroleum plants in Surakhany. The natural eternal flame was extinguished in 1969, after nearly a century of petroleum and gas extraction in the area, and is now maintained using a piped gas supply.[4]

The Baku Ateshgah was a pilgrimage and philosophical centre of Zoroastrians from Northwestern Indian subcontinent, who were involved in trade with the Caspian area via the famous "Grand Trunk Road". The four holy elements of their belief were: ateshi (fire), badi (air), abi (water), and heki (earth). The complex was converted into a museum in 1975. The annual number of visitors to the museum is about 15,000.[5]

The Temple of Fire "Ateshgah" was nominated for inclusion on the List of World Heritage Sites, UNESCO in 1998 by Gulnara Mehmandarova.[5] On December 19, 2007, it was declared a state historical-architectural reserve by decree of the President of Azerbaijan.[6]

Etymology

Summarize

Perspective

The Persian word Atashgah (with Russian/Azerbaijani pronunciation: Atashgyakh/Ateshgah) literally means "home of fire." The Persian-origin term atesh (آتش) means "fire", and is a loanword in Azerbaijani; it is etymologically related to the Vedic अथर्वन् atharvan. Gah (گاہ) derives from Middle Persian and means "throne" or "bed" and it is cognate with Sanskrit gṛha गृह for "house", which in popular usage becomes gah. The name refers to the fact that the site is situated atop a now-exhausted natural gas field, which once caused natural fires to spontaneously burn there as the gas emerged from seven natural surface vents. A historical alternative name for Azerbaijan is Odlar Yurdu, which means "land of fires" in Azerbaijani.[7]

The name Surakhani, the town where the Ateshgah is situated, is likely derived from the Persian word suraakh (سراخ), meaning "hole," and may thus be interpreted as "a region of holes". Alternatively, it could also allude to the fiery glow of the area, stemming from the Persian term sorkh or surkh (سرخ), meaning "red". The Sanskrit etymology of Surakhany conveys the meaning "mine of the gods", derived from sura, meaning "gods", who are opposed to the asuras, or demons. Surakhany in Tati (the language of Surakhany, close to Persian) means “hole with the fountain”.

History

Summarize

Perspective

Atashgah inscriptions

An inscription from the Baku Atashgah. The first line begins: I salute Lord Ganesha (श्री गणेशाय नमः) venerating Hindu God Ganesha, the second venerates the holy fire (जवालाजी, Jwala Ji) and dates the inscription to Samvat 1802 (संवत १८०२, or 1745-46 CE). The Persian quatrain below is the sole Persian inscription on the temple[8] and, though ungrammatical,[8] also refers to the fire (آتش) and dates it to 1158 (١١٥٨) Lunar Hijri, which is also 1745 CE.

An inscribed invocation to Lord Shiva in Sanskrit at the Ateshgah.

An invocation to the Oneness of existence in Guru Granth Sahib

Surakhany is located on the Absheron Peninsula, which is famous for being a locality where oil oozes naturally from the ground and flames burn perpetually — as at Yanar Dagh — fed by natural hydrocarbon vapours issuing from the rock.[9]

Sarah Ashurbeyli notes that the Atsh is distorted Atesh (“fire”) and Atshi-Baguan means “Fires of Baguan”, referring to Baku. The word Baguan comes from the word Baga, which means “God” in Old Persian,[10] and Bhaga.

"Seven holes with eternal fires" were mentioned by German traveler Engelbert Kaempfer, who visited Surakhany in 1683.[11]

Writing in the 10th century, Estakhri mentioned that fire worshippers lived near Baku, presumably on the Apsheron Peninsula.[12] This was confirmed by Movses Daskhurantsi in his reference of the province of Bhagavan (“Fields of the Gods” i.e., “Fire Gods”).[13]

In the 18th century, Atashgah was visited by Zoroastrians. The Persian handwriting Naskh inscription over the entrance aperture of one of the cells, which speaks about the visit of Zoroastrians from Isfahan:

- Persian inscription:

آتشی صف کشیده همچون دک

جیی بِوانی رسیده تا بادک

سال نو نُزل مبارک باد گفت

خانۀ شد رو سنامد (؟) سنة ۱۱۵٨

- Transliteration of Persian inscription:

- ātaši saf kešide hamčon dak

- jey bovāni reside tā bādak

- sāl-e nav-e nozl mobārak bād goft

- xāne šod ru *sombole sane-ye hazār-o-sad-o-panjāh-o-haštom

- Translation:[14]

- Fires stand in line

- Esfahani Bovani came to Badak [Baku]

- "Blessed the lavish New Year", he said:

- The house was built in the month of Ear in year 1158.

The 1158 year corresponds to 1745 AD. Bovan (modern Bovanat) is the village near Esfahan. The word Badak is a diminutive of Bad-Kubeh. (The name of Baku in the sources of the 17th and 18th centuries was Bad-e Kube). At the end of the reference is the constellation of Sombole /Virgo (August–September). In the name of the month the master mistakenly shifted the “l” and “h” at the end of the word. According to Zoroastrian calendar Qadimi New Year in 1745 AD was in August.

Interesting information about Zoroastrianism in Baku is given by D. Shapiro in A Karaite from Wolhynia meets a Zoroastrian from Baku.[15] Avraham Firkowicz, a Karaite collector of ancient manuscripts, wrote about his meeting in Darband in 1840 with a fire-worshipper from Baku. Firkowicz asked him “Why do you worship fire?” The fire-worshipper replied that he worshipped not fire, but the Creator symbolised by fire - a “matter” or abstraction (and hence not a person) called Q’rţ’. Pahlavi Q’rţ’ (from Avestan kirdar or Sanskrit kṛt and कर्ता) signifies “one who does” or “creator”.

Structure

Some scholars have speculated that the Ateshgah may have been an ancient Zoroastrian shrine that was decimated by invading Islamic armies during the Muslim conquest of Persia and its neighboring regions.[16] It has also been asserted that, "according to historical sources, before the construction of the Indian Temple of Fire (Atashgah) in Surakhany at the end of the 17th century, the local people also worshipped at this site because of the 'seven holes with burning flame'."[17]

The present shrine is of Northern Indian rather than of a Persian foundation, especially not of ancient Sasanian origins, but the site itself may have been used by Zoroastrians ages ago.[18]

Fire is considered sacred in Hinduism and Zoroastrianism (as Agni and Atar, respectively),[19][20] and there has been debate on whether the Atashgah was originally a Hindu structure, or a Zoroastrian one. The trident mounted atop the structure is usually a distinctly Hindu sacred symbol (as the Trishula, which is commonly mounted on temples)[21] and has been cited by Zoroastrian scholars as a specific reason for considering the Atashgah as a Hindu site.[22] However, an Azerbaijani presentation on the history of Baku, which calls the shrine a "Hindu temple", identifies the trident as a Zoroastrian symbol of "good thoughts, good words and good deeds".[23] even though the trident symbol is not associated with Zoroastrianism

One early European commentator, Jonas Hanway, grouped Zoroastrians, Sikhs, and Hindus together in terms of their religious beliefs: "These opinions, with a few alterations, are still maintained by some of the posterity of the ancient Indians and Persians, who are called Gebers or Gaurs, and are very zealous in preserving the religion of their ancestors; particularly in regard to their veneration for the element of fire."[24] Geber is a Persian term for Zoroastrians, while Gaurs are a priestly Hindu caste. A later scholar, A. V. Williams Jackson, drew a distinction between the two groups. While stating that "the typical features which Hanway mentions are distinctly Indian, not Zoroastrian" based on the worshipers' attires and tilakas, their strictly vegetarian diets and open veneration for cows, he left open the possibility that a few "actual Gabrs (i.e. Zoroastrians, or Parsis)" may also have been present at the shrine alongside larger Hindu and Sikh groups.[25]

Indian residents and pilgrims

In the late Middle Ages, there were significant Indian communities throughout Central Asia.[26][27] In Baku, Indian merchants from the Multan region of Punjab controlled much of the commercial economy (see also Multani Caravanserai). Much of the woodwork for ships on the Caspian was also done by Indian craftsmen.[24] Some commentators have theorized that Baku's Indian community may have been responsible for the construction or renovation of the Ateshgah.[27][28]

As European scholars and explorers began to arrive in Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent, they documented their encounters with numerous Hindus at the shrine, as well as Sikh pilgrims traveling through the regions between North India and Baku.[24][25][28][29][30]

Samuel Gottlieb Gmelin's Reise durch Russland (1771) is cited in Karl Eduard von Eichwald's Reise in den Caucasus (Stuttgart, 1834) where the naturalist Gmelin is said to have observed Yogi austerities being performed by devotees. Geologist Eichwald restricts himself to a mention of the worship of Rama, Krishna, Hanuman and Agni.[31] In the 1784 account of George Forster of the Bengal Civil Service, the square structure was about 30 yards across, surrounded by a low wall and containing many apartments. Each of these had a small jet of sulphurous fire issuing from a funnel "constructed in the shape of a Hindu altar." The fire was used for worship, cooking and warmth, and would be regularly extinguished.[32]

"The Ateshgyakh Temple looks not unlike a regular town caravansary - a kind of inn with a large central court, where caravans stopped for the night. As distinct from caravansaries, however, the temple has the altar in its center with tiny cells for the temple's attendants - Indian ascetics who devoted themselves to the cult of fire - and for pilgrims lining the walls."[33]

Zoroastrian residents and pilgrims

There is evidence that, in addition to Hindus, the temple was also attended by Zoroastrians, including both Parsis and Guebres, as well as Sikhs. In the 17th century, Jean Chardin reported on Persian Guebres who worshipped an eternally burning fire located on the Absheron Peninsula, two days' journey from Shamakhi.[34]

Engelbert Kaempfer, who visited Surakhany in 1683, wrote that among the people who worshipped fire, two men were descendants of Persians who had migrated to India.[35]

French Jesuit Villotte, who lived in Azerbaijan since 1689, reports that Ateshgah revered by Hindus, Sikhs, and Zoroastrians, the descendants of the ancient Persians.[36]

In 1733, German traveler Johannes Lerch visited the temple and recorded that twelve Guebres, or ancient Persian fire worshippers, were living there.[37]

J. Hanway visited Baku in 1747 and left a few records concerning the Ateshgah. He referred to the fire worshippers there as "Indians," "Persians," and "Guebres".[38]

S. Gmelin, who visited the Ateshgah in 1770, wrote that it was inhabited by Indians and descendants of the ancient Guebres.[39]

In 1820, French consul Gamba visited the temple and reported that it was home to Hindus, Sikhs, and Zoroastrians.[40]

French novelist Alexandre Dumas visited the Ateshgah in 1858 and noted that the only remaining worshippers were an elderly man and two younger men, approximately 30 to 35 years old, one of whom had arrived from India just six months prior.[41]

On September 19, 1863, the Englishman Ussher visited Ateshgah, which he referred to as "Atash Jah." He observed that the site was frequented by pilgrims from India and Persia.[42] In October 1872, German Baron Max Thielmann visited the temple and noted in his memoirs that the Parsi community of Bombay had sent a priest to the site, who would be replaced after a few years. He emphasized the necessity of the priest's presence, as pilgrims from the outskirts of Persia, such as Yazd and Kerman, as well as from India, would come to this sacred place and remain there for several months or even years.[43]

Pierre Ponafidine visited the temple and noted meeting two priests from Bombay.[44] E. Orsolle, who also visited, stated that after the death of the Parsi priest in 1864, the Parsi Panchayat of Bombay sent another priest a few years later. However, by 1880, the pilgrims from India and Iran had largely forgotten the sanctuary, and there was no one left to attend to it.[45] O'Donovan visited the temple in 1879 and described the worship of the Guebres.[46]

In 1898, the magazine Men and Women of India published an article titled "The Ancient Zoroastrian Temple in Baku". The author referred to the Ateshgah as a "Parsi temple" and noted that the last Zoroastrian priest had been sent there approximately 30 years earlier, around the 1860s.[47] In his 1905 book, J. Henry also noted that the last Parsi priest in Surakhani had died approximately 25 years earlier, around 1880.[48]

Inscriptions and likely period of construction

There are several inscriptions on the Ateshgah, numering 17 in total. Fourteen are Hindu, two are Sikh and one alone is Persian. They are all in either Sanskrit or Punjabi, with the exception of one Persian inscription that occurs below an accompanying Sanskrit invocation to Lord Ganesha and Jwala Ji.[25] Although the Persian inscription contains grammatical errors, both the inscriptions contain the same year date of 1745 Common Era (Samvat/संवत 1802/१८०२ and Hijri 1158/١١٥٨).[25][49] Taken as a set, the dates on the inscriptions range from Samvat 1725 to Samvat 1873, which corresponds to the period from 1668 CE to 1816 CE.[25] This, coupled with the assessment that the structure looks relatively new, has led some scholars to postulate the 17th century as its likely period of construction.[16][17][25] One press report asserts that local records exist that state that the structure was built by the Baku Hindu traders community around the time of the fall of the Shirvanshah dynasty and annexation by the Russian Empire following the Russo-Persian War (1722–1723).[50]

The inscriptions in the temple in Sanskrit (in Nagari Devanagari script) and Punjabi (in Gurmukhi script) identify the site as a place of Hindu and Sikh worship,[8][16] and state it was built and consecrated for Jwala Ji,[8] the modern Hindu fire deity. Jwala (जवाला/ज्वाला) means flame in Sanskrit (c.f. Indo-European cognates: proto-Indo-European guelh, English: glow, Lithuanian: zvilti)[51] and Ji is an honorific used in the Indian subcontinent. There is a famed shrine to Jwala Ji in the Himalayas, in the settlement of Jawalamukhi, in the Kangra district of Himachal Pradesh, India to which the Atashgah bears strong resemblance and on which some scholars (such as A. V. Williams Jackson) suggested the current structure may have been modeled.[8] However, other scholars have stated that some Jwala Ji devotees used to refer to the Kangra shrine as the 'smaller Jwala Ji' and the Baku shrine as the 'greater Jwala Ji'.[16] Other deities mentioned in the inscriptions include Ganesha and Shiva. The Punjabi language inscriptions are quotations from the Adi Granth, while some of the Sanskrit ones are drawn from the Sat Sri Ganesaya namah text.[8]

Examination by Zoroastrian priests

In 1876, James Bryce visited the region and found that "the most remarkable mineral product is naphtha, which bursts forth in many places, but most profusely near Baku, on the coast of the Caspian, in strong springs, some of which are said to always be burning." Without referencing the Atashgah by name, he mentioned of the Zoroastrians that "after they were extirpated from Persia by the Mohammedans, who hate them bitterly, some few occasionally slunk here on pilgrimage" and that "under the more tolerant sway of the Czar, a solitary priest of fire is maintained by the Parsee community of Bombay, who inhabits a small temple built over one of the springs".[52]

The temple was examined in the late 19th and early 20th century by Parsi dasturs, some of whom had also visited the Jwala Ji at Kangra in the Himalayas.[53] Based on the inscriptions and the structure, their assessment was that the temple was a Hindu and Sikh shrine.[53] In 1925, a Zoroastrian priest and academic Jivanji Jamshedji Modi traveled to Baku to determine if the temple had indeed been once a Zoroastrian place of worship. Until then (and again today), the site was visited by Zoroastrian pilgrims from India. In his Travels Outside Bombay, Modi observed that "not just me but any Parsee who is a little familiar with our Hindu or Sikh brethren's religion, their temples and their customs, after examining this building with its inscriptions, architecture, etc., would conclude that this is not a [Zoroastrian] Atash Kadeh but is a Hindu Temple whose Brahmins (priests) used to worship fire (Sanskrit: Agni)."[53]

In addition to the physical evidence suggesting that the complex was a Hindu place of worship, its architectural features do not align with those typically found in Zoroastrian or Sikh temples. Notable differences include cells for ascetics, a fireplace open on all sides, an ossuary pit, and the absence of a water source.[53] It cannot be ruled out that the site may once have been a Zoroastrian place of worship. As a Hindu temple, it is considered one of the four major Jwala Ji temples dedicated to the sacred fire.

J. Unvala visited temple in 1935 and noted that its structure is pure Sasanian style.[54]

Exhaustion of the natural gas

The fire was once sustained by seepage from a subterranean natural gas field located directly beneath the complex. However, the extensive exploitation of the natural gas reserves in the area during Soviet rule caused the flame to extinguish in 1969. Today, the shrine's fire is maintained using mains gas supplied from the city of Baku.[55][56]

Alleged visit of Tsar Alexander III

In 1925, locals claimed to a visiting Zoroastrian dastur that during his visit to Baku in 1888, Russian Tsar Alexander III had observed Hindu fire prayer rituals at this site.[57][53] However, this claim has not been verified.[citation needed]

Public recognition

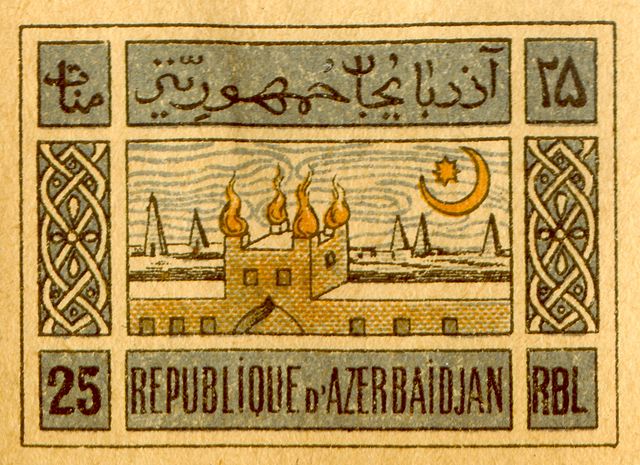

An illustration of the Baku Fire Temple was featured on two denominations of Azerbaijan’s inaugural postage stamp issue, released in 1919, with five oil derricks depicted in the background.[58]

By a presidential decree issued in December 2007, the shrine complex, which had previously been administered as part of the "Shirvanshah Palace Complex State Historical and Architectural Museum-Reserve," was officially designated as a separate reserve named the "Ateshgah Temple State Historical Architectural Reserve".[6]

In July 2009, the Azerbaijani President, Ilham Aliyev, announced a grant of AZN 1 million for the upkeep of the shrine.[59]

In April 2018, the former External Affairs Minister of India, Sushma Swaraj, visited and paid her respects to the shrine.[60]

Gallery

- Plan of the complex

- A Hinduism chamber in the fire temple

- Antiques and stone books

- Indic (above) and Persian (Zoroastrian, below) script from Ateshgyakh. The first line begins: I salute Lord Ganesha (श्री गणेशाय नमः) venerating Hindu God Ganesha, the second venerates the holy fire (जवालाजी, Jwala Ji) and dates the inscription to Samvat 1802 (संवत १८०२, or 1745-46). The Persian quatrain below is the sole Persian inscription on the temple[8] and, though ungrammatical,[8] also refers to the fire (آتش) and dates it to 1158 (١١٥٨) Lunar Hijri, which is also 1745.

- The first six inscriptions at the entrance to one of the chambers of the Ateshgyakh fire-worship temple. It translates: "Bestower of truth, without fear, without hatred, without form of death, without progeny (and) may the self-appearing Guru have mercy on us. May he have mercy on us with the help of the Guru! His disciple was Usasi (Karatarama) who was the gadasi of baba (Ta) who lived in Bamga. Djavaladji (called) (It’s) a holy place."

- External wall.

- General view.

- Central temple.

- Flame.

- Iranian Zoroastrians praying in Ateshgah of Baku.

- A sweeping piazza and the entrance area for the Atashgah fire worshippers' temple

- A Drawing of a cross in stone

See also

References

Further reading

External links and photographs

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.