Architecture of Naples

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Naples' architectural heritage encompasses the events, figures, and designs that have shaped the city's urban and architectural development over the course of nearly three millennia.

Ancient era

Summarize

Perspective

Parthenope

Parthenope, founded on Mount Echia by the Cumaeans in the 8th century BCE, has left behind relatively few traces of its existence, including the remains of a 7th-century BCE necropolis and various clusters of settlement artifacts.

6th century BCE: The refounding as Neapolis

Neapolis, founded in the 6th century BCE, was distinguished by an orthogonal urban plan. This layout featured three main plateiai (later known as the Decumani: Via dei Tribunali, Via Anticaglia, and Via San Biagio dei Librai) oriented east-west, intersected at right angles by approximately twenty narrower stenopoi (later the Cardines), running north-south. These intersections formed rectangular blocks, or insulae, measuring approximately 185 by 35 metres (607 by 115 ft).[2]

The Agora/Forum of Neapolis is aligned with the Decumanus Maximus and remains accessible today through the excavations beneath the foundations of the Basilica of San Lorenzo Maggiore.[3]

This is due to a specific circumstance: during the medieval period, following severe torrential rains, a lahar (mudflow) leveled this area, which originally formed a sort of valley. As a result, the new street level in this section alone was raised by approximately ten meters above the preexisting road network. Conversely, throughout the rest of the historic center, the streets represent an uninterrupted stratification of Greek and Roman road layouts, making them inaccessible beneath the modern city. This unique feature is one of the factors that contribute to the historic centre of Naples being recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Two surviving columns from the Temple of the Dioscuri, located in the forum of Neapolis, can still be seen today on the façade of the nearby Basilica of San Paolo Maggiore[4] In fact, until a devastating seismic event in the 17th century, the façade of the original temple remained entirely intact, as evidenced by various etchings from that period.

In more peripheral locations, thermal buildings and stadiums can still be found. Notably, on Via dell’Anticaglia, sections of walls and buttresses from the ancient Theater—likely the venue where Nero performed as a singer—are visible, having been incorporated into later constructions[5] Currently, an extremely complex restoration project is underway to recover the structure, which remains largely intact but is entirely embedded within later buildings.

Tombs were located outside the city walls; they have been identified on Santa Teresa Hill, at Castel Capuano, in the areas of Santi Apostoli and San Giovanni a Carbonara, as well as between Castel Nuovo and Via Verdi, and beneath Via Medina.

Middle Ages

Summarize

Perspective

During the medieval period, Naples also experienced a significant economic, social, and demographic contraction. Under Angevin rule, in 1262, the city became the capital of the Kingdom of Sicily. However, within a few years, following the expulsion of the Angevins from Sicily, a long period of conflicts began between Naples and Aragonese Sicily.

Among the most significant structures built during this period were Castel Capuano, which facilitated the city's expansion towards the northwestern hinterland; Castel Sant'Elmo, which defended the city from the hills; and Castel dell'Ovo. These three fortresses enabled strategic control over Naples from the northwest, the Vomero hills, and the sea. With the rise of the Angevins, a new fortress, Castel Nuovo (also known as Maschio Angioino), was constructed between 1279 and 1282, inheriting the function of the royal residence of the rulers of Naples.

Among the initiatives promoted by Charles I of Anjou were the reclamation of vast marshy areas, encouragement of private construction, the construction of the Church of Sant'Eligio Maggiore,[6] the Tower of San Vincenzo, a hospital, and a new marketplace, as well as improvements to roads, aqueducts, and irrigation channels.

Modern age

Summarize

Perspective

Aragonese rule

During the Aragonese government, the city saw a significant increase in religious foundations, reducing the available building space within the ancient walls. Naples experienced notable demographic growth during this period, reaching approximately 100,000 inhabitants. Consequently, the Aragonese government decided to expand the city's walls.

The strong ties with the Medici facilitated the arrival of the finest Tuscan architects, who contributed to the construction of aristocratic palaces. These architects also introduced new defensive systems, enhancing the city's fortifications and making them more effective with advanced weaponry.

At the end of the century, the city welcomed the Cosentine architect Giovanni Francesco Mormando, who, alongside local architects influenced by Roman styles—such as Novello da San Lucano.[7] and Gabriele d'Agnolo—initiated a new phase of the Neapolitan Renaissance. This movement gained many followers in the 16th century, including Giovanni Francesco Di Palma, a student and son-in-law of Mormando.

The Spanish viceroyalty

16th century

During the 16th century, Viceroy Don Pedro de Toledo expanded the city's fortifications, effectively doubling the urban area and connecting the three main castles: Castel Nuovo, Castel dell'Ovo, and Castel Sant'Elmo. Among the other significant works of the viceroyalty was the transformation of Castel Capuano into a courthouse, a project led by the renowned local architect Ferdinando Manlio, who had already been appointed as the kingdom's official architect.

Throughout the 16th century, several prominent architects emerged, including Giovanni Francesco Di Palma, Gian Battista Cavagni, Giovanni da Nola, and Ferdinando Manlio. During the second half of the century, the city saw the construction of numerous new religious buildings, which would later shape the Neapolitan Baroque style in the following century. Many architects from this period belonged to religious orders, such as the Franciscan Giuseppe Nuvolo and the Jesuit Giuseppe Valeriano.[8]

XVII secolo

During this century, the city expanded towards the Capodimonte hill, where popular neighborhoods developed, and along the Riviera di Chiaia, which became home to bourgeois districts. Neapolitan architecture remained largely influenced by Mannerism, with only a few Baroque structures being constructed, entrusted to distinguished architects such as Cosimo Fanzago and Dionisio Lazzari. Other architects primarily focused on designing interior decorations for churches and renovating bourgeois palaces.

The most significant Baroque works of the period can be found in the Certosa di San Martino and the Naples Cathedral (Duomo). In the city, Dionisio Lazzari established a highly productive workshop that specialized in designing some of the most exquisite commesso marble ensembles.

18th century

With the outbreak of the War of Spanish Succession, Naples came under Habsburg rule, governed through a series of viceroys. Despite ruling for twenty-seven years, the administration faced significant challenges in addressing the city's urban issues.

The central figure of the first half of the century was Francesco Solimena, who, in addition to being a painter and an outstanding architect, played a crucial role in training other architects who would dominate the scene until the mid-century, including Ferdinando Sanfelice, Giovan Battista Nauclerio, and Domenico Antonio Vaccaro.

In 1734, with the arrival of the Bourbons, Naples regained its independence. One of the first measures taken by Charles III of Bourbon was the taxation of ecclesiastical property, thereby curbing the expansion of sacred lands. Another significant initiative was the demolition of a substantial portion of the city's walls to alleviate congestion. Additionally, in 1740, a new land registry was introduced, known as the onciario cadastre, so named because taxable assets were assessed in ounce. However, the cadastre's major weakness was the complete tax exemption granted to feudal estates, despite their inclusion in the records. In an effort to limit feudal jurisdiction, Bernardo Tanucci spearheaded the approval of a legal decree (prammatica) in 1738, but six years later, the nobility successfully lobbied for its repeal.[11] New architects emerged on the Neapolitan urban scene, including Giuseppe Astarita, Nicola Tagliacozzi Canale, and Mario Gioffredo, the latter embracing the emerging Neoclassical movement. Under Charles III, several architects from diverse backgrounds and external to the local tradition came to prominence, such as Giovanni Antonio Medrano (from Sicily), Antonio Canevari (from Rome), Ferdinando Fuga (from Florence), and Luigi Vanvitelli (a Neapolitan of Dutch origin trained in Rome). These four architects designed palaces, villas, and large complexes in the Baroque style, incorporating classical influences.

At the same time, the area around Mount Vesuvius became increasingly populated, serving as a favored retreat for Neapolitan nobility.

In 1775, during the period when the Map of the Duke of Noja was published by Giovanni Carafa di Noja, Duke of Noja[12] Naples had a population of approximately 350,000 inhabitants.

In 1779, a royal decree established the division of the city into twelve districts: San Ferdinando, Chiaia, Montecalvario, San Giuseppe, Porto, Portanova-Pendino, San Lorenzo, Avvocata, Stella, San Carlo all’Arena, Vicaria, and Mercato.[13] This reorganization also introduced street plaques and house numbers for the first time. However, this system was essentially a revival of the twelve municipal deputations (deputazioni municipali) that had been instituted in the 14th century.[14] The deputations were a natural evolution of the phratries (fratrie), which also numbered twelve and held both religious and political functions. These included the Aristeri and Artemisi near Via Duomo, the Ermei and Eubei near the lower decumanus, the Eumelidi near Monte Echia, the Eunostidi near the Borgo dei Vergini, the Theodati, the Kretondi near what is now Vico SS. Filippo e Giacomo, the Kurmeni, the Panclidi, the Oinonei, and the Antinoiti near San Giovanni Maggiore.[15][16]

Contemporary era

Summarize

Perspective

19th century

The French Interlude and the return of the Bourbons

At the end of the 18th century, inspired by the ideals of the French Revolution, Naples experienced a period of political upheaval that led first to the brief establishment of the Parthenopean Republic (1799). In the early 19th century, following a temporary Bourbon restoration, the city entered a period of Napoleonic occupation.

Joseph Bonaparte, brother of Napoleon, commissioned the leveling of the Santa Teresa hill and the construction of a bridge over the Sanità Valley, projects that facilitated the creation of Corso Napoleone, a grand thoroughfare connecting the Royal Palace with the Capodimonte Palace, thereby ensuring continuity with the existing Via Toledo. In addition, he established the city's cadastral registry and initiated the first suppression of religious orders, repurposing monasteries as residential buildings or public offices.

With the rise of Joachim Murat, a reformist urban and political decentralization program was launched. Despite the enrichment of Naples with significant cultural institutions, the French period was not particularly prosperous.[17] Under Murat's reign, the city expanded to incorporate the villages of Bagnoli, Fuorigrotta, Poggioreale, and Vomero.

Following the Bourbon Restoration, the dynasty regained control. One of its first projects was the completion of Piazza del Plebiscito, initially planned by the French, with the construction of the Royal Pontifical Basilica of San Francesco di Paola, designed by Pietro Bianchi in imitation of the Pantheon. This structure also served to obscure the urban congestion of the Pizzofalcone hill behind it.

In 1839, the Consiglio edilizio (Building Council) was established,[18] consisting of six commissioners—each responsible for two of the city's twelve districts—and twenty-four “detailed” architects, two per district. Among its members were prominent architects such as Antonio Niccolini, Stefano Gasse, Gaetano Genovese, and Errico Alvino, who designed several examples of neoclassical architecture, including Villa Floridiana, Palazzo San Giacomo,[19] Villa Pignatelli, and the Academy of Fine Arts of Naples. The council also oversaw the redesign of the Teatro di San Carlo, the Villa Comunale of Naples, the completion of road projects initiated by the French, such as Via Posillipo, and the restructuring of Via del Piliero, contributing to the city's expansion towards the Vomero hill and Bagnoli.

The Consiglio edilizio played a key role in spreading and perpetuating the neoclassical architectural style, which influenced Neapolitan building traditions well beyond the Unification of Italy. Fueled by interest in the excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii, it remained aligned with the broader European architectural avant-garde.

— Giuliana D'Ambrosio

Urban expansion also continued towards the northern suburban casali.

From 1860 to 1914: Urban renewal with Risanamento

After the unification of Italy, the House of Savoy continued several urban projects initiated by the House of Bourbon, such as the construction of Via Duomo and the completion of Corso Maria Teresa—later renamed Corso Vittorio Emanuele—Europe's first ring road, which still runs along the Vomero hill.[20] Additionally, new districts were developed to the east and west of the city. The western districts, such as Chiaia, were built immediately, while the eastern suburbs were developed only after a major urban renewal project.

These new districts followed different urban planning strategies based on their social purpose. The western neighborhoods, with lower population density, were situated in healthier and more scenic areas and were designed for the wealthy bourgeoisie. Meanwhile, the northern and eastern districts, near the marshlands of the Sebeto River, were densely populated and intended for the working class and lower-income employees.

Naples also saw the emergence of its first industrial zones, particularly in the Bagnoli plain, as evidenced by surviving examples of industrial archaeology.

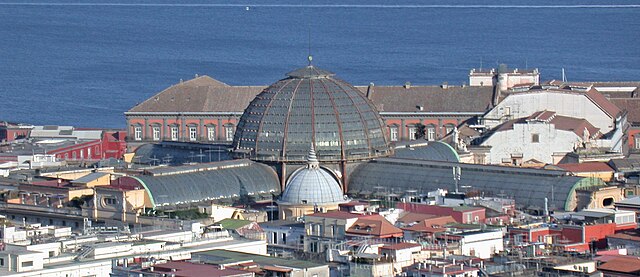

For two decades, the city continued expanding its bourgeois districts toward Chiaia, with the development of Rione Amedeo, Via del Parco Margherita, and Viale Regina Elena (now Viale Gramsci). The extension of Corso Vittorio Emanuele toward Piazza Mazzini, the redevelopment of the areas surrounding Piazza Dante and Piazza Museo Nazionale were also undertaken. These projects included the creation of a new district planned according to modern urban planning principles, with a grid layout and the construction of the Galleria Principe di Napoli, the first shopping gallery in the city.

One of the leading figures in architecture and urban planning during this period was Lamont Young, who proposed the construction of a subway system to connect the working-class districts with the city center and the bourgeois neighborhoods. Some of Young's ideas for this project can be seen in the modern district of Bagnoli, which was developed over two decades under the initiative of Baron Candido Giusso.[21]

The most ambitious project was the redevelopment of the lower city, the area extending towards the sea. These districts were in precarious hygienic and environmental conditions; in fact, in 1884, a cholera outbreak erupted and spread precisely in that area[22] The following year, a law was enacted providing for urban redevelopment, but the projects were implemented only in 1889, with work continuing beyond World War I. This led to the reclamation and infill of the lowest areas near the sea, the construction of Corso Umberto I (perhaps the most significant work of the project), the widening of Via Duomo, the redevelopment of the Santa Brigida area, including the construction of the Galleria Umberto I, and the completion of the Chiaia and Vomero districts. As part of the redevelopment, new districts were built around Piazza Garibaldi, including the so-called ‘‘Case Nuove’’ neighborhood, as well as the Arenaccia district, which expanded the city towards Poggioreale and Secondigliano.[23]

Additionally, the urban redevelopment projects led to the construction of Naples' two oldest funicular railways: the Chiaia funicular and the Montesanto funicular, which connected the newly developed Vomero district with the historic center. In 1910, the section from Mergellina to Campi Flegrei of what is now Line 2 was inaugurated, marking the establishment of Italy's first metropolitan/suburban railway system.

Nevertheless, the redevelopment led to the loss of some historically significant monuments, such as the demolition of the cloisters of San Pietro ad Aram and Sant’Agostino alla Zecca, among other important buildings.

20th century

From 1900 to 1943: Industrialization and fascism

I see the great future Naples, the true metropolis of our Mediterranean — the Mediterranean for Mediterraneans — and I see it, together with Bari (which had sixteen thousand inhabitants in 1805 and now has one hundred and fifty thousand) and Palermo, forming a powerful triangle of strength, energy, and capability. I see Fascism gathering and coordinating all these energies, disinfecting certain environments, removing certain individuals from circulation, and rallying others under its banners.

— Dictator Benito Mussolini

During the redevelopment period, the severity of social conditions and the precarious state of the Neapolitan economy became evident. As a result, in 1904, a new state law promoted industrialization by establishing production plants in Bagnoli and San Giovanni a Teduccio. However, this did not lead to immediate effects, as the proposed conditions set by Francesco Saverio Nitti were not met—such as the expansion of municipal land without encountering the obstacles of the excise tax on goods entering and leaving for production.[23]

With the advent of the Fascist regime, a package of measures was approved for the city. Among these, in addition to the annexation of surrounding hamlets to Naples, there was also the establishment of a High Commission and the founding of the Faculty of Architecture in Palazzo Gravina, which went on to train many of Naples’ most important architects over the decades. In 1939, the new Master Plan was approved, serving as the foundation for post-war urban development. The 12-district division established in 1779 was confirmed, with the urban area expanding to include the districts of Barra, Ponticelli, San Giovanni a Teduccio, and San Pietro a Patierno (annexed on 15 November 1925), as well as the United Colleges (comprising Chiaiano, Marianella, and Piscinola), Secondigliano (including Scampìa and Miano), and Pianura and Soccavo (annexed on 3 June 1926). By the end of these annexations, the municipality had more than doubled in size, and its population had increased by two-thirds, though it did not reach the one million inhabitants hoped for by Benito Mussolini.

The urban transformations carried out during the twenty-year Fascist period mainly focused on central and intermediate areas. These included the construction of the Rione Duca D’Aosta, Rione Miraglia, Rione Sannazzaro, and Rione San Pasquale a Chiaia; the completion of the land reclamation in Santa Lucia for the development of the neighborhood of the same name; the demolition of parts of the San Giuseppe and Carità districts to create new public spaces; the expansion of the port area with the construction of the Maritime Station and the Fish Market; the development of new middle-class neighborhoods; and the construction of the Mostra d’Oltremare.[25] What was attempted during the ventennio was to elevate the local economy to the status of the “Port of the Empire,” granting Naples a privileged position in connections with overseas destinations and colonial possessions. This marked a break from the past, specifically from the Umbertine urban planning introduced at the end of the 19th century, which had emphasized classical and monumental characteristics. [23]

Reconstruction

The damage caused by World War II was severe: the destruction of industries and infrastructure carried out by the retreating Germans was compounded by that of the Allied forces. The reconstruction process took a very long time.[26]

Urban space was considered the crucial resource to be leveraged from both an economic and political perspective. A new version of the PRG in 1946 was, however, rejected by the Achille Lauro administration to align with the interests of the emerging real estate speculation. The 1947 Reconstruction Law granted property owners financing of 80% of the costs needed to restore the destroyed buildings. However, to cover the remaining 20%, many owners decided to sell their reconstruction rights to all kinds of speculators and businessmen, who were then able to operate unchecked.[27]

The intensive construction of the hills and the densification of significant portions of the historic urban fabric drastically altered the city's landscape, reducing green spaces to a minimum. The completion of the clearance of the San Giuseppe district, with the construction of part of the Rione Carità, became an emblematic intervention, highlighted by the erection of the notorious and looming skyscraper of the Società Cattolica delle Assicurazioni, now known as the ‘‘Jolly Hotel’’, a visible symbol of the concept of modernization envisioned at the time. This concept, rooted in rationalism, was interpreted by the architects of the period—Giulio De Luca, Luigi Cosenza, Carlo Cocchia, and Uberto Siola—as a response to the traditional "palace" style that had characterized the Kingdom.[28]

From 1960 to 1980: The new architecture

The residential intensification processes that took place after World War II did not affect only the municipal territory of Naples but also the surrounding municipalities, such as the area between Pozzuoli and the western part of the city or between the Barra district and San Giorgio a Cremano. This led to the formation of a vast conurbation, where degraded and empty suburbs contrasted with a dense flow of commuters traveling to the Historic Centre of Naples, where most commercial activities were concentrated. In response to this urban transformation, Francesco Rosi directed a film on Naples’ real estate speculation titled "Hands Over the City" ("Le mani sulla città") in 1963.

After reducing the impact of speculation, the focus shifted to connecting the suburbs with public transport. Among these projects was the initial plan for the Naples Metro in the 1970s, although its implementation took place in later years, with the opening of the Vanvitelli-Colli Aminei section, which helped reduce traffic congestion and vehicle pollution. Another major infrastructural project was the construction of the Naples Ring Road (Tangenziale), designed to link the municipalities of the conurbation with the central and semi-central districts of the city. The project was first proposed in the 1960s as a strategic choice, influenced by the economic boom and the construction boom.

The decision to build large-scale speculative projects resulted in the creation of major infrastructure, such as the Capodichino Viaduct, which, with its slender pillars, looms over many pre-existing residential buildings, leading to the demolition of others to make way for supporting structures. Additionally, tunnels were dug beneath the city's tuff hills, and daring viaducts were constructed over delicate urban areas.[29]

Urban redevelopment and the 1972 master plan

After the 1980 Irpinia earthquake, several interventions were carried out within the municipal territory, primarily in the central areas, alongside the reconstruction of the suburbs, which saw notable examples of social housing architecture. However, the real turning point came in 1972 with the new Master Plan, which replaced the one from 1939.

Additionally, the plan enabled the implementation of projects proposed during the post-war reconstruction, such as the Via Marittima development. It also facilitated the approval of new public housing projects under Law 167—originally passed a decade earlier and later modified in 1965 and 1971. These new residential neighborhoods were primarily built in the northern areas, such as Scampia, and in the eastern districts, including Ponticelli.[23]

All of this was approved after 1980 through the Emergency Plan for earthquake victims, which also included the redevelopment of various suburban hamlets. This led to the construction of dormitory neighborhoods where lower-income residents were provided with only the bare essentials, without significant investments in strengthening the urban network connecting the historic center with the suburbs. A partial connection was achieved with the opening of the Naples Metro Line 1 Colli Aminei–Piscinola section in 1995.

The urban redevelopment program primarily focused on the historic centre, whose urban fabric was restored after years of neglect. Over the past decade, many noble palaces have been undergoing architectural conversion into cultural associations.

1980s to present

With the construction of new buildings in the northern outskirts of Naples, such as in Scampia and Secondigliano, the 1972 plan was completed, aided by the urgent approval of Law 167. For the first time, the new residential developments were "zoned".

Meanwhile, in the designated industrial zones, deindustrialization took place, severely affecting both the national and local economy. The areas of the former ILVA and Italsider steel plants were declared industrial archaeology.[30]

Many towers were demolished to make way for educational facilities such as Città della Scienza, which acquired a 19th-century industrial pavilion and had it restored by the internationally renowned Neapolitan architect Massimo Pica Ciamarra, becoming one of the most advanced scientific hubs in Italy.

The “football fever” of the World Cup brought renewed hopes for Neapolitan urban planning: all sports facilities were renovated and adapted to maximize seating capacity. However, in some cases, major abuses were committed, such as at the Stadio San Paolo where the original 1950s structure, designed by Carlo Cocchia, was compromised by a steel framework that damaged both its aesthetic and structural integrity.

On 30 May 1994, the "Charter of Megaride" was presented at Castel dell'Ovo, outlining an urban model to be followed by Naples along with eighteen other European cities. The ten fundamental principles of the new “future city” can be summarized as follows: balance between urban and natural environments, quality of life, free access to information, pedestrian and bicycle mobility, horizontal subsidiarity, technological innovation, preservation of existing structures rather than new construction, urban security, administrative efficiency, and historical culture.[31]

Perspectives on urban planning and architecture in Naples

Summarize

Perspective

Historic Centre

The Municipality of Naples has launched a restoration program for historic buildings in partnership with UNESCO, with funding of approximately 240 million euros. The program includes 120 interventions involving not only palaces and churches but also squares and other public spaces to promote the economic and social development of the area.[32] This initiative has been complemented by the establishment of a Limited Traffic Zone (ZTL), as traffic congestion seriously compromises the ability to appreciate the city's aesthetic and historical values.

Centro direzionale

The Centro Direzionale was included in the 1939 urban development plan, but it was only built in the 1990s based on a project by Kenzō Tange and various Neapolitan architects. The new complex was scaled down compared to the original design; several factors, such as the unfinished construction of the adjacent district, led to increased congestion of the main roadways and prevented the development of an alternative rail transport plan, as at the time, the railway system was mainly based on extra-urban lines (the Direttissima, today known as Line 2, the Cumana railway, the Circumvesuviana network, and the Alifana railway).

The current solution, however, features multiple levels: the underground level, also used as parking, connects the Tangenziale with the Industrial Zone, helping to reduce traffic congestion; the surface level is dedicated to commercial and leisure activities, including restaurants and meeting spots; finally, the eastern section is designated for residential use. The building that best showcases the expertise of Neapolitan architects is the pair of Torri ENEL, used as office spaces. These towers are supported by a horizontal beam, itself sustained by two lateral reinforced concrete structures housing service areas, staircases, and elevators.

Periferie

Currently, numerous urban transformation projects are underway: in the west, with the reclamation of Bagnoli through the company Bagnolifutura SPA;[33] in the east, through the ‘‘Consorzio Napoli Est’’ for the redevelopment of areas abandoned by refineries; and in the north, with the establishment of the Faculty of Medicine in Scampia[34] and the completion of Line 1 of the Naples Metro up to the airport.[35]

The inauguration of this major project took place in 1993, about fifteen years after construction began, with the opening of the Vanvitelli-Colli Amineisection, followed in 1995 by the Piscinola Scampia-Colli Aminei section. In 2004, the Vanvitelli-Dante segment was also completed, featuring the contribution of internationally renowned artists who enriched the station interiors with artwork.[36]

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.